Line–line intersection

In Euclidean geometry, the intersection of a line and a line can be the empty set, a point, or a line. Distinguishing these cases and finding the intersection point have use, for example, in computer graphics, motion planning, and collision detection.

In three-dimensional Euclidean geometry, if two lines are not in the same plane they are called skew lines and have no point of intersection. If they are in the same plane there are three possibilities: if they coincide (are not distinct lines) they have an infinitude of points in common (namely all of the points on either of them); if they are distinct but have the same slope they are said to be parallel and have no points in common; otherwise they have a single point of intersection.

The distinguishing features of non-Euclidean geometry are the number and locations of possible intersections between two lines and the number of possible lines with no intersections (parallel lines) with a given line.

Intersection of two lines

A necessary condition for two lines to intersect is that they are in the same plane—that is, are not skew lines. Satisfaction of this condition is equivalent to the tetrahedron with vertices at two of the points on one line and two of the points on the other line being degenerate in the sense of having zero volume. For the algebraic form of this condition, see Skew lines#Testing for skewness.

Given two points on each line

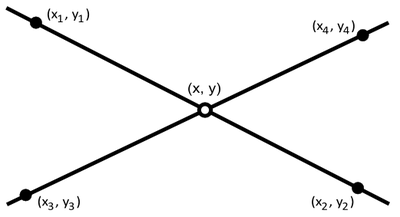

First we consider the intersection of two lines and in 2-dimensional space, with line being defined by two distinct points and , and line being defined by two distinct points and .[1]

The intersection of line and can be defined using determinants.

The determinants can be written out as:

Note that the intersection point is for the infinitely long lines defined by the points, rather than the line segments between the points, and can produce an intersection point beyond the lengths of the line segments. If (rather than solving for the point in a single step), the solution in terms of first degree Bézier parameters is first found, then this intermediate result can be checked for 0.0 ≤ t ≤ 1.0 and 0.0 ≤ u ≤ 1.0 (where t and u are the driving variables).

When the two lines are parallel or coincident the denominator is zero:

If the lines are very close to being parallel, then a computer solution may encounter numeric problems in the solution described above, and so recognition of this condition may require an appropriately "fuzzy" test in practical application. A more robust and general solution may be obtained by rotation of the line segments to drive one of them horizontal, whence the solution of the rotated parametric form of the second line is easily obtained. Careful discussion of the special cases is required (parallel lines/coincident lines, overlapping/non-overlapping intervals).

Given the equations of the lines

The and coordinates of the point of intersection of two non-vertical lines can easily be found using the following substitutions and rearrangements.

Suppose that two lines have the equations and where and are the slopes (gradients) of the lines and where and are the y-intercepts of the lines. At the point where the two lines intersect (if they do), both coordinates will be the same, hence the following equality:

- .

We can rearrange this expression in order to extract the value of ,

- ,

and so,

- .

To find the y coordinate, all we need to do is substitute the value of x into either one of the two line equations, for example, into the first:

- .

Hence, the point of intersection is

- .

Note if a = b then the two lines are parallel. If c ≠ d as well, the lines are different and there is no intersection, otherwise the two lines are identical.

Using homogeneous coordinates

By using homogeneous coordinates, the intersection point of two implicitly defined lines can be determined quite easily. In 2D, every point can be defined as a projection of a 3D point, given as the ordered triple . The mapping from 3D to 2D coordinates is . We can convert 2D points to homogeneous coordinates by defining them as .

Assume that we want to find intersection of two infinite lines in 2-dimensional space, defined as and . We can represent these two lines in line coordinates as and ,

The intersection of two lines is then simply given by,[2]

If the lines do not intersect.

n-line intersection

Existence of and expression for the intersection

In two dimensions

In two dimensions, more than two lines almost certainly do not intersect at a single point. To determine if they do and, if so, to find the intersection point, write the i-th equation (i = 1, ...,n) as and stack these equations into matrix form as

where the i-th row of the n × 2 matrix A is , w is the 2 × 1 vector (x, y)T, and the i-th element of the column vector b is bi. If A has independent columns, its rank is 2. Then if and only if the rank of the augmented matrix [A | b ] is also 2, there exists a solution of the matrix equation and thus an intersection point of the n lines. The intersection point, if it exists, is given by

where is the Moore-Penrose generalized inverse of (which has the form shown because A has full column rank). Alternatively, the solution can be found by jointly solving any two independent equations. But if the rank of A is only 1, then if the rank of the augmented matrix is 2 there is no solution but if its rank is 1 then all of the lines coincide with each other.

In three dimensions

The above approach can be readily extended to three dimensions. In three or more dimensions, even two lines almost certainly do not intersect; pairs of non-parallel lines that do not intersect are called skew lines. But if an intersection does exist it can be found, as follows.

In three dimensions a line is represented by the intersection of two planes, each of which has an equation of the form Thus a set of n lines can be represented by 2n equations in the 3-dimensional coordinate vector w = (x, y, z)T:

where now A is 2n × 3 and b is 2n × 1. As before there is a unique intersection point if and only if A has full column rank and the augmented matrix [A | b ] does not, and the unique intersection if it exists is given by

Nearest point to non-intersecting lines

In two or more dimensions, we can usually find a point that is mutually closest to two or more lines in a least-squares sense.

In two dimensions

In the two-dimensional case, first, represent line i as a point, , on the line and a unit normal vector, , perpendicular to that line. That is, if and are points on line 1, then let and let

which is the unit vector along the line, rotated by 90 degrees.

Note that the distance from a point, x to the line is given by

And so the squared distance from a point, x, to a line is

The sum of squared distances to many lines is the cost function:

This can be rearranged:

To find the minimum, we differentiate with respect to x and set the result equal to the zero vector:

so

and so

In three dimensions

While is not well-defined in more than two dimensions, this can be generalized to any number of dimensions by noting that is simply the (symmetric) matrix with all eigenvalues unity except for a zero eigenvalue in the direction along the line providing a seminorm on the distance between and another point giving the distance to the line. In any number of dimensions, if is a unit vector along the i-th line, then

- becomes

where I is the identity matrix, and so

See also

- Line segment intersection

- Line intersection in projective space

- Distance from a point to a line

- Parallel postulate

References

- ↑ "Weisstein, Eric W. "Line-Line Intersection." From MathWorld". A Wolfram Web Resource. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

- ↑ "Homogeneous coordinates". robotics.stanford.edu. Retrieved 2015-08-18.

External links

- Distance between Lines and Segments with their Closest Point of Approach, applicable to two, three, or more dimensions.