Sail-plan

A sail-plan is a set of drawings, usually prepared by a naval architect which shows the various combinations of sail proposed for a sailing ship. Alternatively, as a term of art, it refers to the way such vessels are rigged as discussed below.

The combinations shown in a sail-plan almost always include three configurations:

- A light air sail plan. Over most of the Earth, most of the time, the wind force is Force 1 or less. Thus a sail plan should include a set of huge, lightweight sails that will keep the ship underway in light breezes.

- A working sail plan. This is the set of sails that are changed rapidly in variable conditions. They are much stronger than the light air sails, but still lightweight. An economical sail in this set will include several sets of reefing ties, so the area of the sail can be reduced in a stronger wind.

- A storm sail plan. This is the set of very small, very rugged sails flown in a gale, to keep the vessel under way and in control.

In all sail plans, the architect attempts to balance the force of the sails against the drag of the underwater keel in such a way that the vessel naturally points into the wind. In this way, if control is lost, the vessel will avoid broaching (turning edge-to-the wind), and being beaten by breaking waves. Broaching always causes uncomfortable motion, and in a storm, the breaking waves can destroy a lightly built boat. The architect also tries to balance the wind force on each sail plan against a range of loads and ballast. The calculation assures that the sail will not knock the vessel sideways with its mast in the water, capsizing and perhaps sinking it.

Terminology

Types of rig

- Fore-and-aft rig features flat sails that run fore and aft. These types of sails are the easiest to manage, because they often do not need to be relaid when the ship changes course. Bermuda rig (also known as a Marconi rig) is a type of fore-and-aft rig with a triangular mainsail.

- Gaff rig features fore-and-aft sails shaped like a triangle minus its point, the upper edge of which is made fast to a spar called a gaff. The top of the sail tends to twist away from the wind reducing its efficiency when close-hauled. However, due to the gaff on the top edge of the sail the centre of effort is typically lower, somewhat reducing the angle of heel (leaning of the boat caused by wind force on the sails) compared to a similar sized Bermuda rigged sail.

- Square rig features sails set square to the mast from a yard, a spar running transversely in relation to the hull (athwartships). In ships built using older designs of the square rig, sailors would have to climb the rigging and walk out on footropes under the yard to furl and unfurl the sails. In a modern square rigged design the crew can furl and unfurl sails by remote control from the deck. Some cruising craft with fore-and-aft sails will carry a small square sail with top and bottom yards that are easily rigged and hauled up from the deck; such a sail is used as the only sail when running downwind under storm conditions, as the vessel becomes much easier to handle than under its usual sails, even if they are severely reefed (shortened). A modern version of this rig is the German-engineered DynaRig which has its yards fixed permanently in place on its rotating masts and has twice the efficiency of operation of the traditional square rig.[1]

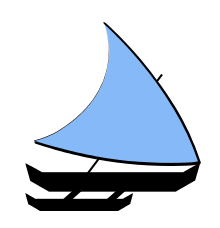

- Lateen rig features a triangular sail set on a long yard, mounted at an angle on the mast and running in a fore-and-aft direction. This is one of the lowest drag (windage) sails.

Types of sail

Each form of rig requires its own type of sails. Among them are:

- A staysail ("stays'l") is a piece of cloth that has one or two sides attached to a stay, that is, one of the ropes or wires that helps hold the mast in place. A staysail was classically attached to the stay with wooden or steel hoops. Sailors would test the hoops by climbing on them.

- A jib is a headsail that flies in front of the foremost vertical mast, whether that be the mainmast or a somewhat shorter foremast.

Order

The standard terminology assumes three masts, from front to back, the foremast, mainmast and mizzenmast. On ships with fewer than three masts, the tallest is the mainmast. Ships with more masts number them.

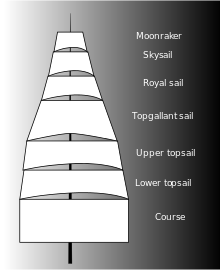

From bottom to top, the sails of each mast are named by the mast and position on the mast, e.g. for the mainmast, from lowest to highest: main course, main topsail, main topgallant ("t'gallant"), main royal, main skysail, and main moonraker. Since the early nineteenth century, the topsails and topgallants are often split into a lower and an upper sail to allow them to be more easily handled. This makes the mast appear to have more "sails" than it officially has.

On many warships, sails above the fighting top (a platform just above the lowest sail) were mounted on separate masts ("topmasts" or "topgallant masts") held in wooden sockets called "tabernacles". These masts and their stays could be rigged or struck as the weather and tactical situation demanded.

In light breezes, the working square sails would be supplemented by studding sails ("stuns'l") out on the ends of the yardarms. These were called as a regular sail, with the addition of "studding". For example, the main top studding sail.

The staysails between the masts are named from the sail immediately below the highest attachment point of the stay holding up the staysail. Thus, the mizzen topgallant staysail can be found dangling from the stay leading from above the mizzen (third) mast's topgallant sail to some place (usually two sails down) on the second (main) mast.

The jibs, staysails between the first mast and the bowsprit were named (from inner to outer most) fore topmast staysail (or foretop stay), inner jib, outer jib and flying jib. All of the jibs' stays meet the foremast just above the fore topgallant. Unusually, a fore royal staysail may also be set.

Material

Sails were classically made of hemp or cotton. They are now made from polyesters (Dacron and PET film), sometimes reinforced with crystalline hydrocarbons (Kevlar and Spectra). Some large, lightweight sails are made of polyamides (nylon).

Lines

In the age of sail, lines were made of manila, cotton, hemp, or jute. Modern lines are made of polyester (Dacron), polyamides (nylon), and sometimes crystallized hydrocarbons (Kevlar and Spectra). Standing rigging may include wire rope made of stainless or galvanized steel. Other older, or less common materials include papyrus in ancient Egypt and coir.

Rigging

- Standing rigging does not change position. Usually it braces the masts.

- Running rigging is used to adjust sails and anchors.

- A line is a rope that has been put to use aboard a sailing vessel.

- A stay is a wire or rope that supports a mast. It is part of the standing rigging, usually located in the fore-aft plane of the vessel.

- A shroud is similar to a stay, but is located in the athwartship plane of the vessel. Thus, shrouds come down to the sides of the boat and are attached to chainplates. Shrouds may be held away from the mast by spreaders.

- A vang is a rope used to pull something around or down.

- A boom vang pulls down on a boom.

- A sheet is a line used to adjust the position of a sail so that it catches the wind properly.

- Halyards (from "haul-yard") are the lines on which one pulls to hoist something; e.g. the main-topgallant-staysail-halyard would be the line on which one pulls to hoist (unfurl) the main-topgallant-staysail.

- A block is the seaman's name for a pulley-block. It may be fixed to some part of the vessel or spars, or even tied to the end of a line.

- The sheave is the wheel within a block, or a spar, over which a line is rove.

- A fiddle block has two or more sheaves in one block, each with its own axle, so the sheaves are aligned.

- A snatch-block can be closed around a line, to grab the line, rather than threading the end of the line through the block.

- A shackle is a piece of metal to attach two ropes, or a block to a rope, or a sail to a rope. Customarily, a shackle has a screw-in pin which often is so tight that a shackle-key must be used to unscrew it. A snap-shackle does not screw, and can be released by hand, but it is usually less strong or more expensive than a regular shackle.

- Running lines are made fast (unmoving) by belaying them to (wrapping them around) a cleat or a belaying-pin located in a pin-rail or fife-rail. Wrapping the rope holds it tight and prevents the line from slipping, i.e. stops it. Thus to "belay" something meant to stop or cease it in naval slang ("belay that noise!").

Sprit and stays

- Bowsprit, a horizontal spar extending from the bow (front) of the boat used to attach the forestay to the foremost mast. Sails which attach to the stays of the bowsprit are called forestaysails.

- Bobstays, a heavy stay directly below the bowsprit attaching on the above the waterline on the stem to the bowsprits end, often the strongest on a ship, frequently made of chain.

- Whisker Stays, any number of pair of stays on either side of the bowsprit and jib boom bracing them against lateral forces

- Jib boom, a horizontal spar completely outboard the vessel and laying on top of the bowsprit. Used to fly the jibs from and attach the upper forestays to the higher masts.

- dolphin striker, Under the tip of the bowsprit runs downward a heavy pole to provide tension to the jib boom

- Martingale backstays, a pair of stays on either side of the bobstay run to the bottom of the dolphin striker sometimes from the cathead

- martingale, a stay that ends from the bottom of the dolphin striker to the end of the jib boom

The stays on a ship roughly form hoops of tension holding the masts up against the wind. Many ships have been "tuned" by tightening the rigging in one area, and loosening it in others. The tuning can create most of the stress on the stays in some ships.

Types of ships

Sailboat types may be distinguished by:

- hull configuration (monohull, catamaran, trimaran),

- keel type (full, fin, wing, centerboard etc.),

- purpose (sport, racing, cruising),

- number and configuration of masts

- sail plan (square and/or fore-and-aft rigged sails).

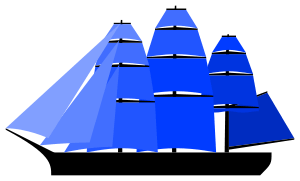

| Sail-plan gallery (detailed descriptions below) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Proa

Constructible using stone age tools, variations on the crab claw sail rig on various sized open ocean canoes carried the Pacific island navigators on regular long range trips. Both ends are alike, and the boat is sailed in either direction, but it has a high windward side and a lower leeward side supported by an outrigger.

Sunfish

A variation on the proa with a single unstayed mast and a single sail, which uses upper and lower spars like a crab claw sail but which pivots around the mast like a lateen. The usage of two straight spars allows for the sails to be cut straight without any camber factored in, making the sails considerably simpler to manufacture.

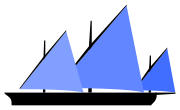

Bragana or felucca

A classic in the Mediterranean or Indian Ocean. Three lateen sails in a row.

Junk

A junk rig is any rig in which the sails are supported by a series of inserts called "battens". The design originated in China, and the term is used regardless of the number of masts the vessel carries. Also, a ship can be rigged with one of its sails as a junk sail and another as a Bermuda rig without being considered a junk vessel. The inserts permit them to sail well on any point of sail, and they are considered easy to maneuver reasonably fast. The nature of the rig places no extreme loads anywhere on the sail or rigging, thus can be built using light-weight, less expensive materials. Junks also customarily had internal water-tight rooms. They remained water-tight because they had no door to other water-tight compartments. Movement was over the wall by ladders or companionways. Usually they were constructed of teak or mahogany.

Catboat

A sailboat with a single mast and single sail, usually gaff-rigged. This is the easiest sail-plan to sail, and is used on the smallest and simplest boats. The catboat is a classic fishing boat. A popular movement among home-built boats uses this simple rig to make "folk-boats". One of the advantages of this type is that it can be rigged with no boom to hit one's head or knock one into the water. However, the gaff requires two halyards and often two topping lifts. The weight of the gaff spar high in the rigging can be undesirable. The gaff's fork (jaws) is held on by a rope threaded through beads called trucks (US) or parrel beads (UK). The gaff must slide down the mast, and therefore prevents any stays from bracing the mast. This usually makes the rig even heavier, requiring yet more ballast.

Sloop

A Bermuda or gaff mainsail lifted by a single mast with a single jib attached to a bowsprit, bent onto the forestay, held taut with a backstay. The mainsail is usually managed with a spar on the underside called a "boom". One of the best-performing rigs per square foot of sail area and is fast for up-wind passages. This rig is the most popular for recreational boating because of its potential for high performance. On small boats, it can be a simple rig. On larger sloops, the large sails have high loads, and one must manage them with winches or multiple purchase block-and-tackle devices.

Gunter

A rig designed for smaller boats where the mast is often taken down. It consists of a relatively short mast (usually slightly shorter than the boat so that it can be stowed inside) and a long gaff (often only slightly shorter than the mast). However, rather than the usual trapezoidal shape of a gaff sail, it is triangular, like a Bermuda rig. This allows the gaff, when hoisted, to pivot upwards until it is vertical, effectively forming an extension to the mast. Thus a decent-sized sailing rig can be added to the boat while still allowing all the equipment to be stowed completely inside it. The popular Mirror class of dinghy is gunter rigged for this reason.

Lugger

A lugger is a two-masted vessel, with for each mast a sail plan similar to a gaff rig. The lug sails it uses, however, do not have gaffs, that attach directly to its masts. Instead, the spars are allowed to move forward and aft of the mast and are managed through a series of lines that attach to the yards and to the corners of the sails. Each sail may or may not have a boom along its foot. In Scotland, when constructed with a main dipping lug sail and a mizzen standing lug sail, such vessels are known as fifies, sailing fifies, or herring drifters; they were often used for herring fishing.

Cutter

A small single-masted ship with a gaff-rigged mainsail and a square-rigged topsail above. Sometimes cutters also had an additional square-rigged mainsail when traveling downwind. The mast was normally set amidships, and two or more headsails were set from the mast to the running bowsprit.[2] Considered better than a sloop for light winds; it is also easier to manage.

Yawl

A small ship, fore-and-aft rigged on its two masts, with its mainmast much taller than its mizzen and with or without headsails. The mizzen mast is located aft of the rudderpost, sometimes directly on the transom, and is intended to help provide helm balance.

Ketch

A small ship with two masts, both fore-and-aft rigged, with the mizzen located well forward of the rudderpost and of only slightly smaller size than the mainmast (if the height of the masts were reversed—the taller in the back and the shorter in the front—it would be considered a schooner). Historically the mainmast was square rigged instead of fore-and-aft, but in modern usage only the latter is called a ketch. The purpose of the mizzen sail in a ketch rig, unlike the mizzen on a yawl rig, is to provide drive to the hull. A ketch rig allows for shorter sails than a sloop with the same sail area, resulting in a lower center of sail and less overturning moment. The shorter masts therefore reduce the amount of ballast and stress on the rigging needed to keep the boat upright. Generally the rig is safer and less prone to broaching or capsize than a comparable sloop, and has more flexibility in sail-plan when reducing sail under strong crosswind conditions—the mainsail can be brought down entirely (not requiring reefing) and the remaining rig will be both balanced on the helm and capable of driving the boat. The ketch is a classic small cargo boat.

Schooner

A fore-and-aft rig having at least two masts, with a foremast that is usually smaller than the other masts. Schooners have traditionally been gaff-rigged and in small craft are generally two-masted, however many have been built with marconi rigs (and even junk rigs) rather than gaffs and in the golden age of sail, vessels were built with as many as seven masts. One of the easiest types to sail, but performs poorly to windward without gaff topsails. The extra sails and ease of the gaff sails make the rig easier to operate, though not necessarily faster, than a sloop on all points of sail other than up-wind. Schooners were more popular than sloops prior to the upsurge in recreational boating. The better performance of the sloop upwind was outweighed for most sailors by the better performance of the schooner at all other, more comfortable, points of sail. Advances in design and equipment over the last hundred years have diminished the advantages of the schooner rig. Many schooners sailing today are either reproductions or replicas of famous schooners of old.

Topsail schooner

This type of vessel has two masts, each made of two spars. The mainmast is rigged exactly like the mainmast of any other schooner (i.e., fore and aft mainsail and gaff rigged topsail) but the foremast, though having the typical schooner's fore and aft rigged mainsail, has above it one or more square rigged topsails. The arrangement requires the ship to have a foremast yard (the lowest) from which no sail hangs. The foremast and all of its sails are comparable to that of a brigantine (see below). If there are square rigged topsails on both masts, then it is called a two topsail schooner or double topsail schooner.[3]

Bilander

The bilander is a two-masted vessel, the foremast carrying square rigs on its all of its yards and its taller mainmast having a long lateen mainsail yard with corresponding trapezoidal sail and rig inclined at about 45° with square rigs on the yards above that, the lowermost secured at the corners by a crossjack. The design was popular in the Mediterranean Sea as well as around New England in the first half of the 18th century, but was soon surpassed by better designs. It is considered the forerunner of the brig.[3]

Brig

In American parlance, the brig encompasses three classes of ship: the full-rigged brig (often simply called a "brig"), the hermaphrodite brig, and the brigantine. All American brigs are defined by having exactly two masts that are entirely or partially square rigged. The foremast of each is always entirely square rigged; variations in the taller mainmast are what define the different subtypes [3] (The definition of a brig, brigantine, etc. has been subject to variations in nation and history, however, with much crossover between the classes).

Full-rigged brig

For the full-rigged brig, the foremast and mainmast each has three spars, all of them square rigged. In addition, the mainmast has a small gaff-rigged sail mounted behind ("abaft") the mainmast.

Hermaphrodite brig

.png)

_fore_course.png)

On a hermaphrodite brig, also called a "half brig" and a "schooner brig", the main mast carries no yards: it is made in two spars and carries two sails, a gaff mainsail and gaff topsail, making it half schooner and half brig (hence its name). If it also carries one or more square-rigged topsails on the mainmast, it is then considered a "jackass brig".[3] Some authors have asserted that this type of sail plan is that of a brigantine.[4]

Brigantine

Like the hermaphrodite brig, a brigantine also has a main (second) mast made in two spars, and its large mainsail is also fore and aft rigged. However, above this it carries two or three square rigged yards instead of a gaff topsail (the hermaphrodite brig retains the gaff topsail), and carries no square rigged sail at all on its lowermost yard of its mainmast (the full-rigged brig retains a square rigged sail in this position, making it very difficult to visually distinguish at a distance from a brigantine).[3]

Snow

Similar to the brig in that it has two masts, both of them square-rigged. Where it differs from the brig is that instead of being attached the mainmast, a fore and aft rigged spanker sail is attached to a small trysail mast just abaft (behind) the mainmast.

Barque

Three masts or more, square rigged on all except the aftmost mast. Usually three or four masted but five masted barques have been built. Lower-speed, especially downwind, but requiring fewer sailors than a ship. This is a classic slow-cargo ship.

Barquentine or Schooner Barque

A three masted vessel, square rigged on the foremast and fore-and-aft rigged on the main and mizzen masts. Some sailors who have sailed on them say it is a poor-handling compromise between a barque and a ship, though having more speed than a barque or schooner.

Polacre

A three master with a narrow hull, carrying a square-rigged foremast, followed by two lateen sails. The same vessel, if she substituted her square-rigged mast with another lateen rigged one, would be called a xebec.

Fully rigged ship

Three or more masts, square rigged on all, usually with stay-sails between masts. The classic ship rig originally had exactly three masts, but four and five masted ships were also built. Occasionally the mizzen mast would have a fore-and-aft sail as its course sail, but in order to qualify as a "fully rigged ship" the vessel would need to have a square-rigged top sail mounted above this (thus distinguishing the fully rigged ship from, say, a barque—see above). The classic sailing warship—the ship of the line—was full rigged in this way, because of high performance on all points of wind. In particular, studding sails or topping sails could be easily added for light airs or high speeds. Square rigs have twice the sail area per mast height compared to triangular sails, and when tuned, more exactly approximate a multiple airfoil, and therefore apply larger forces to the hull. Windage (drag) is more than triangular rigs, which have smaller tip vortices. Therefore, historic ships could not point as far upwind as high performance sloops. However, contemporary marconi rigs (sloops, etc.) were limited in size by the strength of available materials, especially their sails and the running rigging to set them. Ships were not so limited, because their sails were smaller relative to the hull, distributing forces more evenly, over more masts. Therefore, due to their much larger, longer waterline length, ships had much faster hull speeds, and could run down or away from any contemporary sloop or other marconi rig, even if it pointed more upwind. Schooners have a heavier rig and require more ballast than ships, which increases the wetted area and hull friction of a large schooner compared to a ship of the same size. The result is that a ship can run down or away from a schooner of the same hull length. Ships were larger than brigs and brigantines, and faster than barques or barquentines, but required more sailors.

Sail-plan measurements

Every sail-plan has maximum dimensions.[5][6] These maxima are for the largest sail possible and they are defined by a letter abbreviation.

- J The base of the foretriangle measured along the deck from the forestay pin to the front of the mast.

- I The height measured along the front of mast from the jib halyard to the deck.

- E The foot length of the mainsail along the boom.

- P The luff length of the mainsail measured along the aft of the mast from the top of the boom to the highest point that the mainsail can be hoisted at the top of the mast.

- Ey The length of a second boom (For a Ketch or Yawl).

- Py The height of the second mast from the boom to the top of the mast.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Perkins, Tom; Dijkstra, Gerard; Navi, Perini; Roberts, Damon (2004), The Maltese Falcon: the realization (PDF), International HISWA Symposium on Yacht Design and Yacht Construction, retrieved 7 September 2016

- ↑ Nicholas Blake; Richard Lawrence (August 2005). The Illustrated Companion to Nelson's Navy. Stackpole. p. 46. ISBN 978-0-8117-3275-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 John Robinson; George Francis Dow (1922). The Sailing Ships of New England, 1607-1907. Marine Research Society. pp. 28–30.

- ↑ John Harper (30 November 2010). Ghostly Tales on Land and Sea. F+W Media. p. 57. ISBN 978-1-4463-5004-1.

- ↑ Sail Measurement Assistance

- ↑ Sail Measurement

Further reading

- Bolger, Philip C. (1998). 103 Sailing Rigs "Straight Talk". Gloucester, Maine: Phil Bolger & Friends, Inc. ISBN 0-9666995-0-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sail-plan. |

- Atlas du Génie Maritime: Many contemporary plans of 19th century ships, sail plans, deck plans, hull lines