USS Langley (CV-1)

USS Langley underway, 1927 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: |

|

| Namesake: | |

| Builder: | Mare Island Naval Shipyard |

| Cost: |

|

| Laid down: | 18 October 1911 |

| Launched: | 14 August 1912 |

| Commissioned: | 7 April 1913 |

| Decommissioned: | 24 March 1920 |

| Commissioned: | 20 March 1922 |

| Decommissioned: | 25 October 1936 |

| Commissioned: | 21 April 1937 |

| Renamed: | Langley, 21 April 1920 |

| Reclassified: |

|

| Struck: | 8 May 1942 |

| Identification: |

|

| Nickname(s): | "Covered Wagon" |

| Honors and awards: |

|

| Fate: | scuttled, 27 February 1942 |

| Badge: |

|

| Class overview | |

| Name: | Langley-class aircraft carrier |

| Operators: |

|

| Preceded by: | N/A |

| Succeeded by: | Lexington class |

| Built: |

|

| In commission: |

|

| Planned: | 2 |

| Completed: | 1 |

| Lost: | 1 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: |

|

| Displacement: | |

| Length: | 542 ft (165.2 m)[2] |

| Beam: | 65 ft 5 in (19.9 m)[2] |

| Draft: |

|

| Installed power: | |

| Propulsion: |

|

| Speed: | 15.5 kn (17.8 mph; 28.7 km/h) |

| Range: | 3,500 nmi (4,000 mi; 6,500 km) at 10 kn (12 mph; 19 km/h)[2] |

| Complement: |

|

| Armament: |

|

| Aircraft carried: |

|

| Aviation facilities: |

|

USS Langley (CV-1/AV-3) was the United States Navy's first aircraft carrier, converted in 1920 from the collier USS Jupiter (AC-3), and also the US Navy's first turbo-electric-powered ship. Conversion of another collier was planned but canceled when the Washington Naval Treaty required the cancellation of the partially built Lexington-class battlecruisers Lexington and Saratoga, freeing up their hulls for conversion to the aircraft carriers Lexington and Saratoga. Langley was named after Samuel Pierpont Langley, an American aviation pioneer. Following another conversion, to a seaplane tender, Langley fought in World War II. On 27 February 1942, she was attacked by nine twin-engine Japanese bombers[3] of the Japanese 21st and 23rd Naval Air Flotillas[2] and so badly damaged that she had to be scuttled by her escorts.

Service history

Collier

President William H. Taft attended the ceremony when Jupiter's keel was laid down on 18 October 1911 at the Mare Island Naval Shipyard in Vallejo, California. She was launched on 14 August 1912 sponsored by Mrs. Thomas F. Ruhm; and commissioned on 7 April 1913 under Commander Joseph M. Reeves.[4] Her sister ships were Cyclops, which disappeared without a trace in World War I, Proteus, and Nereus, which disappeared on the same route as Cyclops in World War II.

After successfully passing her trials as the first turbo-electric-powered ship of the US Navy, Jupiter embarked a United States Marine Corps detachment at San Francisco, California, and reported to the Pacific Fleet at Mazatlán Mexico on 27 April 1914, bolstering US naval strength on the Mexican Pacific coast in the tense days of the Veracruz crisis. She remained on the Pacific coast until she departed for Philadelphia on 10 October. En route, the collier steamed through the Panama Canal on Columbus Day, the first vessel to transit it from west to east.[4]

Prior to America's entry into World War I, she cruised the Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico attached to the Atlantic Fleet Auxiliary Division. The ship arrived at Norfolk, Virginia on 6 April 1917, and, assigned to the Naval Overseas Transport Service, interrupted her coaling operations by two cargo voyages to France in June 1917 and November 1918. The first voyage transported a naval aviation detachment of 7 officers and 122 men to England.[5] It was the first US aviation detachment to arrive in Europe and was commanded by Lieutenant Kenneth Whiting, who became Langley's first executive officer five years later.[5] Jupiter was back in Norfolk on 23 January 1919 whence she sailed for Brest, France on 8 March for coaling duty in European waters to expedite the return of victorious veterans to the United States. Upon reaching Norfolk on 17 August, the ship was transferred to the West Coast. Her conversion to an aircraft carrier was authorized on 11 July 1919, and she sailed to Hampton Roads, Virginia on 12 December, where she decommissioned on 24 March 1920.[4]

Aircraft carrier

_aerial_view.gif)

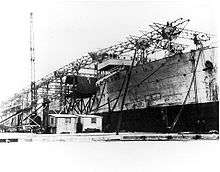

Jupiter was converted into the first US aircraft carrier at the Navy Yard, Norfolk, Virginia, for the purpose of conducting experiments in the new idea of seaborne aviation. On 11 April 1920, she was renamed Langley in honor of Samuel Pierpont Langley, an American astronomer, physicist, aeronautics pioneer and aircraft engineer, and she was given the hull number CV-1. She recommissioned on 20 March 1922 with Commander Kenneth Whiting in command.[4]

As the first American aircraft carrier, Langley was the scene of several seminal events in US naval aviation. On 17 October 1922, Lt. Virgil C. Griffin piloted the first plane—a Vought VE-7—launched from her decks.[6] Though this was not the first time an airplane had taken off from a ship, and though Langley was not the first ship with an installed flight deck, this one launching was of monumental importance to the modern US Navy.[4] The era of the aircraft carrier was born introducing into the navy what was to become the vanguard of its forces in the future. With Langley underway nine days later, Lieutenant Commander Godfrey de Courcelles Chevalier made the first landing in an Aeromarine 39B.[6] On 18 November, Commander Whiting was the first aviator to be catapulted from a carrier's deck.[4][7][8]

An unusual feature of Langley was provision for a carrier pigeon house on the stern between the 5 in (130 mm)/51 caliber guns.[9] Pigeons had been carried aboard seaplanes for message transport since World War I, and were to be carried on aircraft operated from Langley.[9] The pigeons were trained at the Norfolk Naval Shipyard while Langley was undergoing conversion.[10] As long as the pigeons were released a few at a time for exercise, they returned to the ship; but when the whole flock was released while Langley was anchored off Tangier Island, the pigeons flew south and roosted in the cranes of the Norfolk shipyard.[10] The pigeons never went to sea again and the former pigeon house became the executive officer's quarters;[9] but the early plans for conversion of Lexington and Saratoga included a compartment for pigeons.[10]

By 15 January 1923, Langley had begun flight operations and tests in the Caribbean Sea for carrier landings. In June, she steamed to Washington, D.C., to give a demonstration at a flying exhibition before civil and military dignitaries. She arrived at Norfolk on 13 June, and commenced training along the Atlantic coast and Caribbean which carried her through the end of the year. In 1924, Langley participated in more maneuvers and exhibitions, and spent the summer at Norfolk for repairs and alterations, she departed for the west coast late in the year and arrived San Diego, California on 29 November to join the Pacific Battle Fleet.[4]

In 1927, Langley was at the Guantanamo Bay Naval Base.[11] For the next 12 years, she operated off the California coast and Hawaii engaged in training fleet units, experimentation, pilot training, and tactical-fleet problems.[4] Langley was featured in the 1929 silent film about naval aviation The Flying Fleet.[12]

Seaplane tender

.jpg)

_is_hit_by_torpedo_on_27_February_1942.jpg)

On 25 October 1936, she put into Mare Island Navy Yard, California for overhaul and conversion to a seaplane tender. Though her career as a carrier had ended, her well-trained pilots had proved invaluable to the next two carriers, Lexington and Saratoga[4] (commissioned on 14 December and 16 November 1927, respectively).

Langley completed conversion on 26 February 1937 and was assigned hull number AV-3 on 11 April. She was assigned to the Aircraft Scouting Force and commenced her tending operations out of Seattle, Washington, Sitka, Alaska, Pearl Harbor, and San Diego, California. She departed for a brief deployment with the Atlantic Fleet from 1 February-10 July 1939, and then steamed to assume duties with the Pacific Fleet at Manila arriving on 24 September.[4]

World War II

On the entry of the US into World War II, Langley was anchored off Cavite, Philippines.[4][13] On 8 December, following the invasion of the Philippines by Japan, she departed Cavite for Balikpapan, in the Dutch East Indies. As Japanese advances continued, Langley departed for Australia, arriving in Darwin on 1 January 1942.[13] She then became part of the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDACOM) naval forces. Until 11 January, Langley assisted the Royal Australian Air Force in running anti-submarine patrols out of Darwin.[4][13]

Langley went to Fremantle, Australia to pick up Allied aircraft and transport them to Southeast Asia. Carrying 32 P-40 fighters belonging to the Far East Air Force's 13th Pursuit Squadron (Provisional).[13] At Fremantle Langley and Sea Witch, loaded with crated P-40s, joined a convoy designated MS.5 that had arrived from Melbourne composed of the United States Army Transport Willard A. Holbrook and the Australian transports Duntroon and Katoomba escorted by Phoenix departed Fremantle on 22 February.[4][14] Langley and Sea Witch left the convoy five days later to deliver the planes to Tjilatjap (Cilacap), Java.[4][14]

In the early hours of 27 February, Langley rendezvoused with her anti-submarine screen, the destroyers Whipple and Edsall.[4][13] Early that morning, a Japanese reconnaissance aircraft located the formation. At 11:40, about 75 mi (121 km) south of Tjilatjap, the seaplane tender, along with Edsall and Whipple came under attack by sixteen (16) Mitsubishi G4M "Betty" bombers of the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service's Takao Kōkūtai, led by Lieutenant Jiro Adachi, flying out of Den Pasar airfield on Bali, and escorted by fifteen (15) A6M Reisen fighters. Rather than dropping all their bombs at once, the Japanese bombers attacked releasing partial salvos. Since they were level bombing from medium altitude, Langley was able to alter helm when the bombs were released and evade the first and second bombing passes, but the bombers altered their tactics on the third pass and bracketed the directions Langley could turn. As a result, Langley took five hits from a mix of 250 and 60 kilograms (550 and 130 pounds) bombs as well as three near misses,[15] with 16 crewmen were killed.[16][note 1] The topside burst into flames, steering was impaired, and the ship developed a 10° list to port.[4][13] Unable to negotiate the narrow mouth of Tjilatjap harbor, Langley went dead in the water, as her engine room flooded. At 13:32, the order to abandon ship was passed.[4] The escorting destroyers fired nine 4-inch (100 mm) shells and two torpedoes into Langley's hull,[4] to ensure she didn't fall into enemy hands, and she sank. (Her approximate scuttle coordinates are: S 8° 51′ 04.20″ × E 109° 02′ 02.56″ Ap)[13] After being transferred to Pecos, many of her crew were lost when Pecos was sunk en route to Australia.[18] Thirty-one of the thirty-three pilots assigned to the 13th Pursuit Squadron being transported by Langley were lost with Edsall when she was sunk on the same day while responding to the distress calls of Pecos.[13]

Film appearance

Langley appears in several scenes of The Flying Fleet, a 1929 silent film about naval aviators.[12]

Awards and decorations

| As Jupiter[19] | |

| Mexican Service Medal | World War I Victory Medal with "Transport" clasp |

| As Langley[19] | ||

| American Defense Service Medal with "Fleet" clasp |

Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal | World War II Victory Medal |

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Note that some English language sources rely on Roscoe [17]which incorrectly attributes the attack to nine Aichi D3A1 "Val" dive bombers of the Japanese 21st and 23rd Naval Air Flotillas, however Langley's own action report (no longer available online?) cited the attackers as twin-engined horizontal bombers, which the report compared to German Junkers Ju 86 bombers; and the multiple passes taken would be impossible for dive bombers with a single bomb each, to carry out.

Citations

- ↑ "Table 21 - Ships on Navy List June 30, 1919". Congressional Serial Set. U.S. Government Printing Office: 766. 1921.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Ford et al. 2001, p. 330

- ↑ USN 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 "Langley I (AC-3)". Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. Navy Department, Naval History & Heritage Command.

- 1 2 Tate 1978, p. 62

- 1 2 Tate 1978, p. 66

- ↑ Tate 1978, p. 67

- ↑ Though catapults had already been used for launching aircraft from ships – e.g. Henry C. Mustin in 1915 from the cruiser North Carolina

- 1 2 3 Tate 1978, p. 65

- 1 2 3 Pride 1979, p. 89

- ↑ "U.S. Navy National Museum of Naval Aviation photo No. 2003.001.323". collections.naval.aviation.museum. Retrieved 26 April 2015.

- 1 2 Kaplan, Philip (2013). Naval Air: Celebrating a Century of Naval Flying. Pen and Sword. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-78159-241-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Birkett, Gordon. "P-40's in Australia – Part 5" (PDF). www.adf-serials.com. Retrieved 16 May 2013.

- 1 2 Gill 1957, pp. 601—602.

- ↑ Java Sea 1943.

- ↑

- Messimer, Dwight (1983). Pawns of War: The Loss of the USS Langley and the USS Pecos. Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute.

- ↑ Roscoe 1953, p. 102

- ↑ DANFS entry for USS Pecos (AO-6)

Bibliography

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

- "USS Langley (CV-1) (formerly Jupiter (Collier #3); later AV-3)". NavSource Online. 10 July 2016. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- Ford, Roger; Gibbons, Tony; Hewson, Rob; Jackson, Bob; Ross, David (2001). The Encyclopedia of Ships. London: Amber Books Ltd. p. 330. ISBN 978-1-905704-43-9.

- Gill, G. Hermon (1957). Royal Australian Navy 1939–1942. Australia in the War of 1939–1945. Series 2 – Navy. 1. Canberra: Australian War Memorial. LCCN 58037940.

- Messimer, Dwight (1983). Pawns of War: The Loss of the USS Langley and the USS Pecos. Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute.

- Pride, A.M. VADM USN (January 1979). "Comment and Discussion". United States Naval Institute Proceedings: 89.

- Roscoe, Theodore (1953). United States Destroyer Operations In World War II. Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 0-87021-726-7.

- Tagaya, Osamu. Mitsubishi Type 1 Rikko Betty Units of World War 2. ISBN 1-84176-082-X.

- Tate, Jackson R, RADM USN (October 1978). "We Rode the Covered Wagon". United States Naval Institute Proceedings.

- "A Brief History of U.S. Navy Aircraft Carriers Part IIa - The War Years (1941-1942)". Official Website of the United States Navy. 15 June 2009. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- "The Java Sea Campaign Combat Narratives". OFFICE OF NAVAL INTELLIGENCE - UNITED STATES NAVY. 1943. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

- Images of USS Langley (CV-1) in the Naval History and Heritage Command's Photo Archive

- Image archive at San Diego Air & Space Museum Archives

- Langley at NavSource.org

- Video of early landings aboard USS Langley (CV-1) circa 1922

Coordinates: 8°51′S 109°2′E / 8.850°S 109.033°E