Ukrainians in Russia

| Total population | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Languages | |

| Russian language (99.8%, 2002) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Ukrainians, other Slavic peoples especially East Slavs |

The Ukrainians in Russia make up the largest single diaspora of the Ukrainian people. The official census in 2010 reported that 1.9 million Ukrainians lived in Russia, representing over 1.4% of the total population of the Russian Federation and comprising the third-largest ethnic group after ethnic Russians and Tatars. An estimated 340,000 people born in Ukraine (mostly youths) permanently settle in Russia each year legally.[2]

History

Early history

Grand Prince of Kiev Vladimir II Monomakh founded the principality of Vladimir-Suzdal, and his son Yuri Dolgoruki founded the city of Moscow in 1147. However, by the end of the 12th century the prominence of Rus' began to decline as Kiev's central role became disputed by the surrounding principalities which were increasingly more powerful and independent. Dolgoruki's son Andrei I Bogolyubsky plundered Kiev in 1169, an event that allowed the Principality of Vladimir-Suzdal to take a leading role as the predecessor of the modern Russian state.

The sacking of Kiev itself in December 1240 during the Mongol Invasion led to the ultimate collapse of the Rus' state. For many of its residents, the brutality of Mongol attacks sealed the fate of many choosing to find safe haven in the North East. In 1299, the Kievan Metropolitan Chair was moved to Vladimir by Metropolitan Maximus, keeping the titile of Kiev. As Vladimir-Suzdal, and later the Grand Duchy of Moscow continued to grow unhindered, the Orthodox religious link between them and Kiev remained strong. Envoys continued to be sent to Moscow from the Kiev Pechersk Lavra. Professional artisans, builders, craftsmen and lay-people also traveled to Moscow where they could more easily earn a living.

The Southern Ruthenians found themselves within a new state of Grand Duchy of Lithuania. After the union of Jogaila and Kingdom of Poland in 1386 this state became officially Catholic in leadership. This isolated its majority Orthodox population, and soon many notable Ruthenian leaders began to leave for Moscow. In 1408 a group of nobles led by Švitrigaila along with the Chernihiv bishop together with a significant group of soldiers defected to Moscow. Others followed. Trade though initially sporadic, traveling through Chernihiv and Putyvl.

The frequent Russo-Lithuanian Wars meant that in 1448, Moscow Metropolitan Jonah, despite of the fall of Byzantium, achieved full Autocephaly for the Russian Orthodox Church. The title of Kiev remained with the Kievan Metropolia, which was under the jurisdiction of the Patriarch of Constantinople.

The emigration to the Tsardom of Russia continued to grow in the 16th century. Prominent examples include Michael Glinski who staged a powerful rebellion against Lithuanian rule in February 1508 all those that took part in the uprising, who would receive a boyar title along with villages and lands around Medyn for settlement. In the mid-16th century the Ukrainian Hetman Dmytro Vyshnevetsky visited Moscow where he served in the court of Tsar Ivan IV and received in return the city of Belyov on the river Tula and surrounding villages and homesteads as rewards. Trade also grew considerably in this period, and many Ukrainian Slobodas were founded in Russian cities.

Many Ukrainian settlers settled in areas that lay between the old Zasechnaya cherta and the new defence line that would guard Russia from the frequent raids by the Nogais and the Crimean Tatars. This became known as Sloboda Ukraine, and initial forts, such as Kursk, Voronezh and Kharkiv were founded and settled by Ukrainian peasants that served the garrisons stationed there. According to the writings of the English trader D. Fletcher in 1588, these garrison towns had 4300 soldiers of which 4000 had come from Ukraine. The number of Ukrainian settlers in the southern borders of Russia increased after the unsuccessful revolts against the Poles. As a result, the bulk of the population became mixed.

17th and 18th centuries

After the Treaty of Pereyaslav of 1654, migration to Russia from Ukraine increased. Initially this was to Sloboda Ukraine, but also to the Don lands and the area of the Volga river. There was also a significant migration to Moscow, particularly by church activists: priests and monks, scholars and teachers, artists, translators, singers and merchants. A colony was built in Moscow called the Malorossiysky dvor. In 1652 12 singers under the direction of Ternopolsky moved to Moscow, 13 graduates of the Kiev-Mogilla Collegium moved to teach the Moscovite gentry. Many priests and church administrators migrated from Ukraine, in particular the established Andreyevsky Monastery was made up from Ukrainian clergy. This had a great effect on the Russian Orthodox Church, and the policies of Patriarch Nikon which led to the Old Believer Raskol (schism). The influence of Ukrainian clergy continued to grow, especially after 1686, when the Metropolia of Kiev was transferred from the Patriarch of Constantinople to the Patriarch of Moscow.

Soon after, the abolishment of the Patriarch's chair by Peter I, the Ukrainian Stephen Yavorsky became Metropolitan of Moscow, followed by Feofan Prokopovich. Demetrius of Rostov became of Tobol and Siberia, and from 1704 Rostov and Yaroslavl. In all over 70 positions in the Orthodox hierarchy were taken by recent emigres from Kiev. Students of the Kiev-Mohyla Collegium started up schools and seminaries in many Russian eparchies. By 1750, over 125 such institutions were opened. As a result, these graduates practically controlled the Russian church obtaining key posts there (and holding them to almost the end of the 18th century). Under Prokopovich the Russian Academy of Sciences was opened in 1724 which was chaired from 1746 by Ukrainian Kirill Razumovsky.[3]

The Moscow court had a choir established in 1713 with 21 singers from Ukraine. The conductor for a period of time was A. Vedel. In 1741 44 male, 33 women, and 55 girls were moved to St. Petersburg from Ukraine to sing and entertain. In 1763 the head conductor of the Emperor's court choir was M. Poltoratsky and later Dmitry Bortniansky. Composer Maksym Berezovsky also worked in St. Petersburg at the time. A significant Ukrainian presence was also seen in the Academy of Arts.

The Ukrainian presence in the Russian Army also grew significantly. The greatest influx happened after the Battle of Poltava in 1709. Large numbers of Ukrainians settled around St Petersburg and were employed in the building of the city, the various fortresses and canals.

A separate category of emigrants were those deported to Moscow by the Russian government for demonstrating anti-Russian sentiment. The deported were brought to Moscow initially for investigation, and then exiled to Siberia, Arkhangelsk or the Solovetsky Islands. Among the deported were Ukrainian cossack luminaries as D. Mhohohrishny, Ivan Samoylovych and Petro Doroshenko. Others include all the family of hetman Ivan Mazepa, A. Vojnarovsky, and those in Mazepa's Cossack forces that returned to Russia. Some were imprisoned in exile for the rest of their lives such as hetmanPavlo Polubotok, Pavlo Holovaty, P. Hloba and Petro Kalnyshevsky.

19th century

Beginning in the 19th century, there was a continuous migration from Belarus, Ukraine and Northern Russia to settle the distant areas of the Russian Empire. The promise of free fertile land was an important factor for many peasants who until 1861, lived under Serfdom. In the colonization of the new lands, a significant contribution was made by ethnic Ukrainians. Initially Ukrainians colonised border territories in the Caucasus. Most of these settlers came from Left-bank Ukraine and Slobozhanshchyna and mainly settled in the Stavropol, and Terek areas. Some compact areas of the Don, Volga and Urals were also settled.

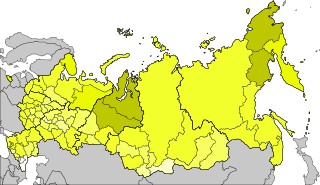

The Ukrainians created large settlements within Russia often becoming the majority in certain centres. They continued fostering their traditions, their language and their architecture. Their village structure and administration differed somewhat from the Russian population that surrounded them.[4] Where populations were mixed, russification often took place.[4] The size and geographical area of the Ukrainian settlements were first seen in the course of the Russian Empire Census of 1897. This census noted only language, not ethnicity. Nonetheless a total of 22,380,551 Ukrainian speakers were recorded. Within the European territories of Russia 1,020,000 Ukrainians, in Asia (not including the Caucasus) 209,000 were recorded. From 1897-1914, the intense migration of Ukrainians to the Urals and Asia continued, and was measured to be 1.5 million before ceasing in 1915.

20th century

Formation of Ukrainian borders

The first Russian Empire Census, conducted in 1897 gave statistics regarding language use in the Russian Empire according to the administrative borders. Extensive use of Little Russian (and in some cases dominance) was noted in the nine south-western Governorates and the Kuban Oblast.[5] When the future borders of the Ukrainian state were marked, the results of the census were taken into consideration. As a result, the ethnographic borders of Ukraine in the 20th century were twice as large as the Cossack Hetmanate that was incorporated into the Russian Empire in the 17th.[6]

Certain regions had mixed populations made up of both Ukrainian and Russian ethnicities as well as other minorities. These include the territory of Sloboda and the Donbass. These territories were between Ukraine and Russia. This left a large community of ethnic Ukrainians on the Russian side of the border. The borders of the short-lived Ukrainian People's Republic were largely preserved by the Ukrainian SSR.

In the course of the mid-1920s, the course of administrative reforms some territory, initially under the Ukrainian SSR was ceded to the Russian SFSR, such as the Taganrog and Shakhty cities in the eastern Donbass. At the time, the Ukrainian SSR gained several territories that were amalgamated into the Sumy Oblast in Sloboda region.

Soviet-time migration

The Soviet Union was officially a multicultural country with no official national language. On paper all languages and cultures were guaranteed state protection Union-wide. In reality, however, the Ukrainians were granted the opportunity to meaningfully develop their culture only within the administrative borders of the Ukrainian Republic, where the Ukrainians had a privileged status of being the titular nation. As many Ukrainians migrated to other parts of the USSR, the cultural separation often led in their assimilation, particularly within Russia, which received the highest percentage of the Ukrainian migration. In Siberia, 82% of Ukrainians entered mixed marriages, primarily with Russians. This meant that outside the Ukrainian SSR, there was little or no provision for continuing a diaspora function. As a result, Ukrainian-language press was soon found only in large cities such as Moscow. Ukrainian cultural attributes such as clothing and national foods were preserved. According to Soviet sociologist, 27% of the Ukrainians in Siberia read printed material in Ukrainian and 38% used the Ukrainian language. From time to time, Ukrainian groups would visit Siberia. Nonetheless, most of the Ukrainians there did assimilate.

Due to the fact that Ukrainians were prominent in the Gulags of Norilsk and Vorkuta Ukrainians have continued to be the majority ethnicity in these cities. Around 80% of the population in Norilsk in 1989 had least one Ukrainian ancestor.

According to Volodymyr Kubiyovych and Aleksandr Zhukovsky the area of Ukrainian ethnic territory outside of the borders of the Ukrainian SSR (1970) where an ethnic Ukrainian majority lived was estimated to be 146,500 square kilometres, and the area of nationally mixed territories make up approximately 747,600 square kilometres.

Ukrainian life in post-Soviet Russia

The Ukrainian cultural renaissance in Russia began at the end of the 1980s, with the formation of the Slavutych Society in Moscow and the Ukrainian Cultural Centre named after T. Shevchenko in Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg).

In 1991, the Ukraina Society organized a conference in Kiev with delegates from the various new Ukrainian Community organizations of the Eastern Diaspora. By 1991, over 20 such organizations were in existence. By 1992, 600 organizations were registered in Russia alone. The Congress helped to consolidate the efforts of these organizations. From 1992, regional congresses began to take place, organized by the Ukrainian organizations of Prymoria, Tyumen Oblast, Siberia and the Far East. In March 1992, the Union of Ukrainian organizations in Moscow was founded. In May of that year - The Union of Ukrainians in Russia.

The term "Eastern Diaspora" has been used since 1992 to describe Ukrainians living in the former USSR, as opposed to the Western Ukrainian Diaspora which was used until then to describe all Ukrainian diaspora outside the Union. An estimated number of Ukrainians living in the Eastern Diaspora is 6.8 million, and while those in the West is approximately 5 million.

in the 2010 census the city with the largest amount of Ukrainians as a percentage of its population was Norilsk where Ukrainians made up to 50.6% of the population however 30% more of the population of norilsk is believed to be Ukrainian but unaware of it .(see Norilsk for further information)

In February 2009 about 3.5 million Ukrainian citizens were estimated to be working in the Russian Federation, especially in Moscow and in the construction industry.[7] According to Volodymyr Yelchenko, the Ambassador of Ukraine to the Russian Federation there were no state schools in Russia with a program for teaching school subjects in the Ukrainian language as of August 2010; he considered "the correction of this situation" as one of his top priority tasks.[8]

Many Ukrainians also come illegally so the true number of Russian Ukrainians is unknown the number of Ukrainian illegal immigrants varies from 3-11 million. Many Ukrainians are viewed as illegalls and criminals and many complain of racism. Some have compared this to how Mexicans are viewed in the United States.[9]

Events since the Euromaidan

During the 2014 Crimean crisis and 2014 pro-Russian conflict in Ukraine Ukrainians living in Russia complained of being labelled a "Banderite" (follower of Stepan Bandera); even when they were from parts of Ukraine were Stephan Bandera has no popular support.[10]

Refugees from the War in Donbass

According to the Russian federal migration service there have been 2.6 million new Ukrainian citizens living in Russia since January 1, 2014.[11] These are refugees from the territories of Donetsk and Luhansk People's Republics taken over by pro-Russian rebels since 2014 during the War in Donbass. Most of the refugees head to rural areas in central Russia. Major destinations for Ukrainian migrants include Karelia, Vorkuta, Magadan Oblast (oblasts such as Magadan and Yakutia are destinations due to a government relocation program) since the vast majority avoid big cities.[12]

Religion

The vast majority of Ukrainians in Russia are adherents of the Russian Orthodox Church, as stated above, the Ukrainian clergy had a very influential role on Russian Orthodoxy in the 17th and 18th centuries.

Recently, the growing economic migrant population from Galicia have had success in establishing a few Ukrainian Catholic churches, and there are several churches belonging to the Ukrainian Orthodox Church (Kiev Patriarchate), where Patriarch Filaret agreed to accept breakaway groups that had been excommunicated by the Russian Orthodox Church for breaches of canon law.

Some assert that Russian bureaucracy regarding religion has hampered the expansion of the two groups above.[13] According to the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, their denomination has only one church building in all of Russia[14]

Compact Ukrainian population centres in Russia

Kuban

The original Black Sea Cossacks colonised the Kuban region from 1792. Following the Caucasus War and the subsequent colonisation of the Circaucasus, the Black Sea Cossacks intermixed with other ethnic groups including the indigenous Cirsassian population.

According to the 1897 census, 47.3% of the Kuban population (including extensive latter 19th-century non-Cossack migrants from both Ukraine and Russia) referred to their native language as Little Russian (the official term for the Ukrainian language) while 42.6% referred to their native language as Great Russian.[15] Most of the cultural production in Kuban from the 1890s until the outbreak of World War I in 1914, such as plays, stories and music were written in the Ukrainian language,[16] and one of the first political parties in Kuban was the Ukrainian Revolutionary Party.[16] During the Russian Civil War with the Kuban Cossack Rada desperate for survival, turned to the Ukrainian People's Republic and formed a military alliance, as well declaring Ukrainian to be the official language of the Kuban National Republic. This decision was not supported uniformly by the Cossacks themselves and soon the Rada itself was dissolved by the Russian WhiteDenikin's Volunteer Army.[16]

In the 1920s a policy of Decossackization was pursued. At the same time, the Bolshevik authorities supported policies that promoted the Ukrainian language and self-identity, opening 700 Ukrainian-language schools and a Ukrainian department in the local university.[17] Russian historians claim that Cossacks were in this way forcibly[18] Ukrainized, while Ukrainian historians claim that Ukrainization in Kuban merely paralleled Ukrainization in Ukraine itself, where people were being taught in their native language. According to the 1926 census, there were nearly a million Ukrainians registered in the Kuban Okrug alone (or 62% of the total population)[19] During this period many Soviet repressions were tested on the Cossack lands, particularly the Black Boards that led to the Soviet famine of 1932-1934 in the Kuban. Yet by the mid-1930s there was an abrupt policy change of Soviet attitude towards Ukrainians in Russia. In the Kuban, the Ukrainization policy was halted and reversed.[20] In 1936 the Kuban Cossack Chorus was however re-formed as were individual Cossack regiments in the Red Army. By the end of the 1930s many Cossacks' descendants chose to identify themselves as Russians.[21] From that moment onwards almost all of the self-identified Ukrainians in the Kuban, date to non-Cossacks, the Soviet Census of 1989 showed that a total of 251,198 people in Krasnodar Kray (including Adyghe Autonomous Oblast) who were born in the Ukrainian SSR,[22] and moved there by time of census. In the 2002 census, the number of people who identified themselves as Ukrainians in the Kuban was recorded to be 151,788. Despite the fact that most of the Kuban Cossacks descendants do not think of themselves as being nationally Ukrainians, and identify themselves as Russian nationals.,[23] many elements of their unique culture originates from Ukraine, such as the Kuban Bandurist music, and the dialect called Balachka which they speak.[20]

Moscow

Moscow has had a significant Ukrainian presence since the 17th century. The original Ukrainian settlement, bordered Kitai-gorod. No longer having a Ukrainian character, it is today is known as Maroseyka (a corruption of Malorusseyka, or Little Russian). During Soviet times the main street, Maroseyka, was named after the Ukrainian Cossack hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky. After Moscow State University was founded in 1755, from its inception many students from Ukraine studied there. Many of these students had commenced their studies at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy.

In the first years after the revolution of 1905, Moscow was one of the major centres of the Ukrainian movement for self-awareness. The magazine Zoria was edited by A. Krymsky and from 1912-17 the Ukrainian cultural and literary magazine "Ukrainskaya zhizn'" was also published there edited by Symon Petliura. Books in the Ukrainian language were published in Moscow from 1912 and Ukrainian theatrical troops of M. Kropovnytsky and M. Sadovsky were constantly performing there.

Moscow's Ukrainians played an active role in opposing the attempted coup in August 1991.[24]

According to the 2001 census, there are 253,644 Ukrainians living in the city of Moscow,[25] making them the third largest ethnic group in that city, after Russians and Tatars. A further 147,808 Ukrainians live in the Moscow region. The Ukrainian community in Moscow operates a cultural centre on Arbat Street (who's head is apointed by the Ukrainian government),[26] publishes two Ukrainian-language newspapers, and has organized Ukrainian-language Saturday and Sunday schools.

Saint Petersburg

When Saint Petersburg was the capital during the Russian Empire era, many people from all nations including Ukrainians moved there. The Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko, and Dmytro Bortniansky spent most of their lives and died there. Ivan Mazepa, carrying out the orders of Peter I, was responsible for sending many Ukrainians to help build St Petersburg, where they died on a massive scale.[27]

According to the latest census, there are 87,119 Ukrainians living in the city of St Petersburg, where they constitute the largest non-Russian ethnic group.[28] The former Mayor, Valentina Matviyenko (née Tyutina) was born in Khmelnytskyi Oblast of western Ukraine and is of Ukrainian ethnicity .

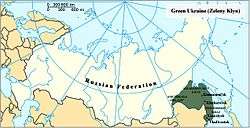

Zeleny Klyn

Zeleny Klyn is often referred to as Zelena Ukraina. This is an area of land settled by Ukrainians which is a part of the Far Eastern Siberia located on the Amur River and the Pacific Ocean. It was named by the Ukrainian settlers. The territory consists of over 1,000,000 square kilometres and has a population of 3.1 million (1958). The Ukrainian population in 1926 made up 41%-47% of the population . In the last Russian census, 94,058 people in Primorsky Krai claimed Ukrainian ethnicity,[29] making Ukrainians the second largest ethnic group and largest ethnic minority.

Siry Klyn

The Ukrainian settlement of Siry Klyn (literally: the "grey wedge") developed around the city of Omsk in western Siberia. M. Bondarenko, an emigrant from Poltava province, wrote before World War I: "The city of Omsk looks like a typical Moscovite city, but the bazaar and markets speak Ukrainian". All around the city of Omsk stood Ukrainian villages. The settlement of people beyond the Ural mountains began in the 1860s. Altogether before 1914 1,604,873 emigrants from Ukraine settled the area. According to the 2010 Russian census, 77,884 people of the Omsk region identified themselves as Ukrainians, making Ukrainians the third-largest ethnic group there, after Russians and Kazakhs.[30]

Zholty Klyn

The settlement of Zholty Klyn (the Yellow Wedge) was founded soon after the Treaty of Pereyaslav of 1659 as the eastern border of the second Zasechnaya Cherta. Named after the yellow steppes on the middle and lower Volga, the colony co-existed with the Volga Cossacks; colonists primarily settled around the city of Saratov. In addition to Ukrainians, Volga Germans and Mordovians migrated to Zholty Klyn in numbers. As of 2014 most of the population is mixed in the region, though a few "pure" Ukrainian villages remain.[31]

Siry klyn Ukrainian community portal

Norilsk

Norilsk was originally founded as a sieries of Gulags that mostly included Ukrainian collaborators with the Nazi Germany who were from western Ukraine (unlike most other Ukrainians in Russia who are from the east). Norilsk is the only inhabited locality in Russia (excluding Villages) with a Ukrainian majority. Ukrainians make up 59-80 percent of Norilsks population. Many of their descendants keep their Ukrainian identity. Norilsk has notably accepted refugees from Ukraine due to family ties with Ukraine.

Far East

Large numbers of Ukrainians live in the Russian far east as a result of the Soviet population transfers, most of them are descendants of the deportees.

Demographics

Statistics and scholarship

Statistical information about Ukrainians in the Eastern diaspora from census materials of the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union and the Russian Federation was collected in 1897, 1920, 1923, 1926, 1937, 1939, 1959, 1970, 1979, 1989, 2002 and 2010. Of which, only the 1937 census has been discarded and a semi-fixed 1939 census was carried out.

In the aftermath of the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, attention has been focused on the Eastern Ukrainian diaspora by the Society for relations with Ukrainians outside of Ukraine. Numerous attempts have been made to unite them. The journal "Zoloti Vorota" began to be published by the Society for relations with Ukrainians outside of Ukraine and also the magazine "Ukrainian Diaspora" in 1991.

| N | Census year | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1926 | 6,871,194 | 7.41 |

| 2 | 1939 | 3,359,184 | 3.07 |

| 3 | 1959 | 3,359,083 | 2.86 |

| 4 | 1970 | 3,345,885 | 2.57 |

| 5 | 1979 | 3,657,647 | 2.66 |

| 6 | 1989 | 4,362,872 | 2.97 |

| 7 | 2002 | 2,942,961 | 2.03 |

| 8 | 2010 | 1,927,988[32] | 1.40 |

| 9 | 2015 est | 6,000,000 | 4 |

Trends

During the 1990s, the Ukrainian population in Russia has noticeably decreased. This was caused by a number of factors. The most important one was the general population decline in Russia. At the same time, a lot of Economic migrants from Ukraine moved to Russia for better paid jobs and careers. It is estimated that there are as many as 300 000[33] legally registered migrants. In wake of negative sentiments to the bulk of Worker migrants from the Caucasus and Central Asians, Ukrainians are thus often more trusted by the Russian population. Assimilation is also an important factor in the falling number of Ukrainians. Due to their dispersal and cultural similarity to Russians, Ukrainians often end up marrying Russians and their children are counted as Russian on the census. Otherwise the Ukrainian population has mostly remained stable due to high amounts of immigration from Ukraine.

Anti-Ukrainian sentiment in Russia

Ukrainians in the Russian Federation represent a sizable minority in the country and the third largest ethnic group after Russians and Tatars. In spite of their relatively high numbers, some Ukrainians in Russia complain of the unfair treatment and the prevailing anti-Ukrainian sentiment in the Russian Federation.[34][35] In November 2010, the High Court of Russia cancelled registration of one of the biggest civic communities of the Ukrainian minority, the "Federal nation-cultural autonomy of the Ukrainians in Russia" (FNCAUR).[36]

Notable Ukrainians in Russia

- Eduard Limonov (Savenko) - Founder of National Bolshevik Party

Culture

- Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (quarter Ukrainian) - Composer

- Ilia Lagutenko - musician

- Stepan Petrichenko

- Mikhail Zoshchenko - Writer

Sports

- Nikolay Davydenko - Tennis player

- Aleksander Emelianenko Mixed martial arts fighter (Ukrainian father, Russian mother)

- Andrei Nikolishin - Ice hockey player; Olympic Bronze medal winner

- Roman Pavlyuchenko - Kuban Ukrainian soccer player for the Russian national football team

- Vladislav Tretiak - Ice hockey goaltender; 3 time Olympic gold medalist; 10 time world champion; considered one of the greatest of all time.

Science

Soviet/Russian Politics

Minister of Defence of Soviet Union

- Andrei Grechko - (1967–76)

Head of State of the USSR

- Konstantin Chernenko - (1984–85)

See also

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 г.: Национальный состав населения Российской Федерации [Russian Population Census 2010: National composition of the population of the Russian Federation]. Russian Federal Service of State Statistics (in Russian). Demoscope.ru. 21 March 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ↑ "MPC Migration Profile: Ukraine" (PDF). European University institute, Migration Policy Centre. June 2013. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ Kagramanov, Yuri (2006). Война языков на Украине [The War of Languages in Ukraine]. Novy Mir. magazines.russ.ru. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- 1 2 Kubiyovych (ed) Entsyklopedia Ukrainoznavstva Vol.7, p.2597

- ↑ 1897 Census on Demoscope.ru Retrieved on 20 May 2007.

- ↑ Kulchitsky, Stanislav (26 January 2006). Империя и мы [The Empire and We]. Den (in Russian). day.kiev.ua. Archived from the original on 17 June 2009. Retrieved 19 March 2007.

- ↑ "Nearly 3.5 million Ukrainians work in Russia". unian.info. 25 February 2009. Archived from the original on 27 February 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- ↑ Yelchenko wants Ukrainian secondary school to operate in Moscow, Kyiv Post (August 19, 2010)

- ↑ Düvell, Franck. "Research Resources Report 1/3: Country Profile: Ukraine – Europe's Mexico?" (PDF). Centre on Migration Policy and Society, School of Anthropology, University of Oxford. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 December 2014.

- ↑ Russia's Ukrainian minority under pressure, Al Jazeera English (25 April 2014)

A ghost of World War II history haunts Ukraine’s standoff with Russia, Washington Post (25 March 2014) - ↑ Weir, Fred (1 December 2015). "Ukrainian refugees in Russia: Did Moscow fumble a valuable resource?". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ↑ Malinkin, Mary Elizabeth; Nigmatullina, Liliya (4 February 2015). "The Great Exodus: Ukraine's Refugees Flee to Russia". The National Interest. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ↑ Lozynskyj, Askold S. (30 January 2002). "The Ukrainian World Congress regarding the census in Russia". Ukrainians of Russia – Kobza. Archived from the original on 2 December 2007.

- ↑ "The first Catholic church in Russia built in the Byzantine style has been blessed". ugcc.org.ua. 24 October 2007. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007.

- ↑ Demoscope.ru, 1897 census results for the Kuban Oblast

- 1 2 3 The politics of identity in a Russian borderland province: the Kuban neo-Cossack movement, 1989-1996, by Georgi M. Derluguian and Serge Cipko; Europe-Asia Studies; December 1997 URL

- ↑ Ukraine and Ukrainians Throughout the World, edited by A.L. Pawliczko, University of Toronto Press, 1994. ISBN 0-8020-0595-0

- ↑ Shambarov, Valery (2007). Kazachestvo Istoriya Volnoy Rusi. Algoritm Expo, Moscow. ISBN 978-5-699-20121-1.

- ↑ Kuban Okrug from the 1926 census demoscope.ru

- 1 2 Zakharchenko, Viktor (1997). Народные песни Кубани [Folk songs of the Kuban]. geocities.com (in Russian). Archived from the original on 11 February 2002. Retrieved 7 November 2007.

- ↑ Kaiser, Robert (1994). The Geography of Nationalism in Russia and the USSR. Princeton University Press, New Jersey. ISBN 0-691-03254-8.

- ↑ Demoscope.ru Soviet Census of 1989, population distribution in region by region of birth.Retrieved 13 November 2007

- ↑ "Russian census 2002". Retrieved 2007-04-22.

- ↑ Trylenko, Larysa (29 December 1991). "The coup: Ukrainians on the barricades". The Ukrainian Weekly. ukrweekly.com. LIX (52). Archived from the original on 20 May 2006.

- ↑ Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года - Москва [National Population Census 2002 - Moscow] (in Russian). Demoscope.ru. 19 September 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ "Kyiv-appointed head of Ukrainian Cultural Center in Moscow intimidated by Russian personnel". Unian.info. 21 September 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ Kraliuk, Petro (7 July 2009). "Mazepa's many faces: constructive, tragic, tragicomic". The Day. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года - Санкт Петербург [National Population Census 2002 - St. Petersburg] (in Russian). Demoscope.ru. 19 September 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года - Приморский край [National Population Census 2002 - Primorsky Krai] (in Russian). Demoscope.ru. 19 September 2016. Retrieved 27 September 2016.

- ↑ Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года: Приморский край [Russian Population Census 2002: Primorsky Krai] (in Russian). Demoscope.ru. 2002. Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ↑ Zhelty Klin website

- ↑ Национальный состав населения Российской Федерации 2010 г. [National composition of the population of the Russian Federation in 2010]. Russian Federation - Federal State Statistics Service (in Russian). Retrieved 3 June 2016.

- ↑ Украинцы в России: еще братья, но уже гости - О "средне-потолочной" гипотезе про 4 миллиона "заробітчан" в РФ и бесславном конце "Родной Украины" [Ukrainians in Russia: still brothers, but now guests - On the "medium ceiling" hypothesis on 4 million "(Ukrainian) workers" in the RF and the inglorious end of "Mother Ukraine"] (in Russian). Ukrainians of Russia – Kobza. 18 June 2006. Archived from the original on 10 November 2007.

- ↑ Открытое письмо Комиссару национальных меньшинств ОБСЕ господину Максу Ван дер Стулу [Open letter to the Commissioner for National Minorities for the OSCE, Mr. Max van der Stoel] (in Russian). Ukrainians of Russia - Kobza. 30 September 2000. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 20 November 2007: Open letter to the OSCE from the Union of Ukrainians in the Urals.

- ↑ Гарантуйте нам в Росії життя та здоров'я! [Guarantee us life and health in Russia!] (in Ukrainian). Ukrainians of Russia - Kobza. 31 December 2006. Archived from the original on 21 March 2008. Retrieved 20 November 2007: Letter to President Putin from the Union of Ukrainians in Bashkiria.

- ↑ Nalyvaichenko, Valentyn (26 January 2011). "Nalyvaichenko to OSCE: Rights of Ukrainians in Russia systematically violated". KyivPost. Archived from the original on 14 September 2011.

Sources

- Kubiyovych, Volodymyr. Entsykolpedia Ukrainoznavstva Vol. 7.

- Українське козацтво - Енциклопедія - Kyiv, 2006

- Zaremba, S. (1993). From the national-cultural life of Ukrainians in the Kuban (1920 and 1930s). Kyivska starovyna. pp. 94–104.

- Lanovyk, B.; et al. (1999). Ukrainian Emigration: from the past to the present. Ternopil.

- Petrenko, Y. (1993). Ukrainian cossackdom. Kyivska starovyna. pp. 114–119.

- Польовий Р. Кубанська Україна К. Дiокор 2003.

- Ratuliak, V. (1996). Notes from the history of Kuban from historic times until 1920. Krasnodar.

- Сергійчук В. Українізація Росії К. 2000

Internet site for Ukrainians in Russia

External links

- Races of Europe 1942-1943 (English)

- Hammond's Racial map of Europe 1923 (English)

- Peoples of Europe / Die Voelker Europas 1914 (German)

- Ethnographic map of Europe 1914 (English)