Ukrainian diaspora

| Part of a series on |

| Ukrainians |

|---|

|

| Diaspora |

|

see Template:Ukrainian diaspora |

| Closely-related peoples |

|

East Slavs (parent group) Boykos · Hutsuls · Lemkos · Rusyns Poleszuks · Kuban Cossacks Pannonian Rusyns |

| Culture |

|

Architecture · Art · Cinema · Cuisine Dance · Language · Literature · Music Sport · Theater |

| Religion |

|

Eastern Orthodox (Ukrainian) Greek Catholicism Roman Catholicism Judaism (among ethnic Jews) |

| Languages and dialects |

|

Ukrainian Russian · Canadian Ukrainian · Rusyn · Pannonian Rusyn Balachka · Surzhyk · Lemko |

|

History · Rulers List of Ukrainians |

The Ukrainian diaspora is the global community of ethnic Ukrainians, especially those who maintain some kind of connection, even if ephemeral, to the land of their ancestors and maintain their feeling of Ukrainian national identity within their own local community.

History

1608 To 1880

After the loss suffered by the Ukrainian-Swedish Alliance under Ivan Mazepa in the Battle of Poltava in 1709, some political emigrants, primarily Cossacks, settled in Turkey and in Western Europe.

In 1775, after the fall of the Zaporozhian Sich to the Russian Empire, some more of the Cossacks emigrated to Dobruja in the Ottoman Empire (now in Romania), while others settled in Volga and Ural regions of the Russian Empire.

In the second half of the 18th century, Ukrainians from the Transcarpathian Region formed agricultural settlements in Hungary, primarily in the Bačka and Syrmia regions. Both these places are currently located in the Vojvodina Region of the Republic of Serbia.

In time, Ukrainian settlements emerged in the major European capitals, including Vienna, Budapest, Rome and Warsaw.

In 1880, the Ukrainian diaspora consisted of approximately 1.2 million people, which represented approximately 4.6% of all Ukrainians, and was distributed as follows:

- 0.7 million Ukrainians in the European part of the Russian Empire;

- 0.2 million Ukrainians in Austro-Hungary;

- 0.1 million Ukrainians in the Asian part of the Russian Empire;

- 0.1 million Ukrainians in the United States.

1880-1920

In the last quarter of the 19th century due to the agrarian resettlement, a massive emigration of Ukrainians from Austro-Hungary to the Americas and from the Russian Empire to the Urals and Asia (Siberia and Kazakhstan) occurred.

A secondary movement was the emigration under the auspices of the Austro-Hungarian government of 10,000 Ukrainians from Galicia to Bosnia.

Furthermore, due to Russian agitation, 15,000 Ukrainians left Galicia and Bukovina and settled in Russia. Most of these settlers later returned.

Finally in the Russian Empire, some Ukrainians from the Chełm and Podlaskie regions, as well as most of the Jews, emigrated to the Americas.

Some of the Ukrainians that left their homeland returned. For example, from the 393,000 Ukrainians that emigrated to the United States of America, 70,000 Ukrainians returned.

Most of the emigrants to the United States of America worked in the construction and mining industries. Many worked in the US on a temporary basis, to earn remittances.

In the 1890s, Ukrainian agricultural settlers emigrated to first to Brazil, and Argentina. However, the writings of Galician professor and nationalist Dr. Joseph Oleskiw were influential in redirecting that flow to Canada. He visited an already-established Ukrainian block settlement, which had been founded by Iwan Pylypiw, and met with Canadian immigration officials. His two pamphlets on the subject praised the United States as a place for wage labour, but stated that Canada was the best place for agricultural settlers to obtain free land. By contrast he was fiercely critical of the treatment Ukrainian settlers had received in South America. After his writings, the slow trickle of Ukrainians to Canada, greatly increased.

Before the start of the First World War, almost 500,000 Ukrainians emigrated to the Americas. This can be broken down by country as follows:

- to the United States of America: almost 350,000 Ukrainians;

- to Canada: almost 100,000 Ukrainians;

- to Brazil and Argentina: almost 50,000 Ukrainians.

In 1914, the Ukrainian diaspora in the Americas was about 700-750 thousand people, located as follows:

- 500-550 thousand Ukrainians in the United States of America;

- almost 100 thousand Ukrainians in Canada;

- approximately 50 thousand Ukrainians in Brazil;

- 15-20 thousand Ukrainians in Argentina.

Most of the emigrates to the Americas belonged to the Greek Catholic Church. This led to the creation of Greek Catholic bishops in Canada and the United States of America. The need for solidarity lead to the creation of Ukrainian religious, political, and social organisations. These new Ukrainian organisations maintained links with the homeland, from which books, media, priests, cultural figures, and new ideas arrived. Furthermore, local influence, as well as influence from their homeland, led to the process of a national re-awakening. At times, the diaspora was ahead of their times in this re-awakening.

It should be noted that the emigrants from the Transcarpathian and Lemko regions created their own organisations and had their own separate Greek Catholic church hierarchy (Ruthenian Catholic Church). These emigrants are often considered to be Rusyns or Ruthenians and are considered by some to be distinct from other Ukrainians. However, in Argentina and Brazil, immigrants from Transcarpathia and Lemkivshchyna did identify themselves as Ukrainians.

The majority of the Ukrainian diaspora in the Americas focused on freeing the nation and obtaining independence. Thus, during the First World War and the fight for freedom in Ukraine (1919–1920), the Ukrainian diaspora in the United States of America and Canada actively sought to get the governments to support their cause. An interesting note is the role the Ruthenians played to convince the United States' government to unite in 1919, the Transcarpathian region with the Czechoslovak Republic. The Ukrainian diaspora sent delegates to the Paris Peace Conference.

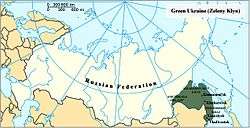

On the other hand, the Ukrainian diaspora in the Russian Empire, and especially in Asia, was primarily agrarian. After 1860, the diaspora was primarily located in the Volga and Ural Regions, while in the last quarter of that century, due to a lack of space for settlement, the diaspora expanded into Western Siberia, Turkestan, the Far East, and even into the Zeleny Klyn. In the 1897 census, in the Russian Empire, there were 1,560,000 Ukrainians divided as follows:

- In the European part of the empire: 1,232,000 Ukrainians

- In the Volga and Urals: 393,000 Ukrainians;

- In the non-Ukrainian (ethnographically speaking) parts of Kursk and Voronezh Regions: 232,000 Ukrainians;

- Almost 150,000 Ukrainians in Bessarabia.

- In the Asian part of the empire: 311,000 Ukrainians

- In the Caucasus region: 117,000 Ukrainians.

In the next decades, Ukrainian emigration to Asia increased (almost 1.5 million Ukrainians emigrated), so that in 1914 there were almost 2 million Ukrainians in the Asian part of the Russian Empire. In all of the Russian empire, there was a Ukrainian diaspora of 3.4 million Ukrainians. Most of this population was assimilated due to a lack of national awareness and closeness with the local Russian population, especially in religion.

Unlike the emigrants from Austro-Hungary, the Ukrainian emigrants in the Russian Empire did not create their own organisations nor were there many interactions with their homeland. Only, the revolution of 1917 allowed the creation of Ukrainian organisations, which were linked with the national and political rebirth in Ukraine.

1920-1945

First major political emigration

The First World War and the Russian Civil War led to the first massive political emigration, which strengthened the existing Ukrainian communities by infusing them with members from political, scientific, and cultural backgrounds. Furthermore, some of these new emigrants formed Ukrainian communities in Western and Central Europe. Thus, new communities were created in the Czechoslovakia, Germany, Poland, France, Belgium, Austria, Romania, and Yugoslavia. The largest was in Prague, which was considered one of the centres of Ukrainian culture and political life (after Lviv and Kraków).

This group of emigrants created many different organisations and movements associated with corresponding groups in the battle for independence. A few Ukrainian universities were founded. Furthermore, many of these organisations were associated with the exiled Ukrainian government, the Ukrainian People's Republic.

During the 1920s, the new diaspora maintained links with the Soviet Ukraine. A Sovietophile movement appeared, whereby former opponents of the Bolsheviks began to argue that Ukrainians should support the Soviet Ukraine. Some argued that they should do so because the Soviet republics were the leaders of international revolution, while others claimed that the Bolsheviks' social and national policies benifted Ukraine. This movement included Mykhailo Hrushevskyi, Volodymyr Vynnychenko and Yevhen Petrushevych. Many émigrés, for example Mykhailo Hrushevskyi, returned and helped the Bolsheviks implement their policy of Ukrainianisation. However, the abandonment of Ukrainianisation, the return to collectivisation and the man-made famine of 1932-3 ended this tendency.[1] Most of the links were broken, with the exception of some Sovietophile organisations in Canada and the United States of America.[2]

On the other hand, the Canadian and American diaspora maintained links with the Ukrainian community in Galicia and the Transcarpathian Region.

The political emigration decreased in the middle 1920s due to a return to the homeland and a decline in students studying at the Ukrainian universities.

Economic emigration

In 1920-1921, Ukrainians left Western Ukraine to settle in the Americas and Western Europe. Most of the emigrates settled in Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, Paraguay, France, the UK and Belgium. The economic crisis of the early 1930s stopped most of the emigration. Later, the emigration picked up. The number of emigrants can be approximated as:

- to Canada: almost 70,000 Ukrainians;

- to Argentina: 50,000 Ukrainians;

- to France: 35,000 Ukrainians;

- to the United States of America: 15,000 Ukrainians;

- to Brazil: 10,000 Ukrainians;

- to Paraguay and Uruguay: a couple of thousand Ukrainians.

Furthermore, many Ukrainians left the Ukrainian SSR and settled in Asia due to political and economic factors, primarily collectivisation and the famine of 1920.

Size

The Ukrainian diaspora, outside of the Soviet Union, was 1.7-1.8 million people, divided by place as follows:

- In the Americas:

- In the United States of America: 700-800 thousand Ukrainians

- In Canada: 250 thousand Ukrainians

- In Argentina: 220 thousand Ukrainians

- In Brazil: 80 thousand Ukrainians

- In Western and Central Europe:

- In Romania (almost all in Bessarabia): 350 thousand Ukrainians

- In Poland: 100 thousand Ukrainians

- In France: 40 thousand Ukrainians

- In Yugoslavia: 40 thousand Ukrainians

- In Czechoslovakia: 35 thousand Ukrainians

- In other countries: 15-20 thousand Ukrainians

According to the soviet census of 1926, there were 3,450,000 Ukrainians living outside of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, divided as follows:

- In the European part of the Soviet Union: 1,310,000 Ukrainians

- 242,000 Ukrainians living on land neighbouring the Ukrainian ethnic territory

- 771,000 Ukrainians in the Volga and Ural regions

- In the Asian part of the Soviet Union: 2,138,000 Ukrainians

- 861,000 Ukrainians in Kazakhstan

- 830,000 Ukrainians in Siberia

- 315,000 Ukrainians in the Far East

- 64,000 Ukrainians in Kyrgyzstan

- 33,000 Ukrainians in the Central Asian Republic

- 35,000 Ukrainians in the Caucasus Region.

In Siberia the vast majority of the Ukrainians lived in the Central Asian region and in the Zeleny Klyn. On January 1, 1933, there were about 4.5 million Ukrainians (larger than the official figures) in the Soviet Union outside of the Ukrainian SSR, while in America there were 1.1-1.2 million Ukrainians.

In 1931, the Ukrainian diaspora can be counted as follows:

| Country | Number (thousands) |

| Soviet Republics | 9,020 |

| Poland | 6,876 |

| Romania | 1,200 |

| USA | 750 |

| Czechoslovakia | 650 |

| Canada | 400 |

| Rest | 368.5 |

| In all | 19,264.5 |

In the Ukrainian SSR, there were 25,300,278 Ukrainians.

1945-1991

Outside the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe

The Ukrainian diaspora increased after 1945 due to a second wave of political emigrants. The 250,000 Ukrainians at first settled in Germany and Austria. In the latter half of the 1940s and early 1950s, these Ukrainians were resettled in many different countries creating new Ukrainian settlements in Australia, Venezuela, and for a time being in Tunisia (Ben-Metir), as well as re-enforcing previous settlements in the United States of America, Canada (primarily Toronto, Ontario and Montreal, Quebec), Brazil, Argentina and Paraguay. In Europe, there remained between 50,000 and 100,000 Ukrainians that settled in the United Kingdom, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands.

This second wave of emigrants re-invigorated Ukrainian organisations in the Americas and Western Europe. In 1967, in New York City, the World Congress of Free Ukrainians was created. Scientific organisations were created. There was created an Institute of Ukrainian Studies at Harvard.

An attempt was made to unite the various religious organisations (Orthodox and Greek Catholic). However, this did not succeed. In the early 1970s, the Ukrainian Orthodox Church in the United States of America and the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church in Europe, South America, and Australia managed to unite. Most of the other Orthodox churches maintained with each other some religious links. The Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church had to wait until 1980 until its synod was recognised by the Vatican. The Ukrainian Evangelical and Baptist churches also created an All-Ukrainian Evangelical-Baptist Union.

Within the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe

During the latter Soviet time there was a strong net migration in the USSR. Most of the Ukrainian contingent that was leaving the Ukrainian SSR for other areas of the Union settled in places with other migrants. The cultural separation from Ukraine proper meant that many were to form the so-called "multicultural soviet nation". In Siberia, 82% of Ukrainian entered mixed marriages, primarily with Russians. This meant that outside the parent national republic there was little or no provision for continuing a diaspora function. Thus only in large cities such as Moscow would Ukrainian literature and television could be found. At the same time other Ukrainian cultural heritage such as clothing and national foods were preserved. According to Soviet sociologist, 27% of the Ukrainians in Siberia read Ukrainian printed material and 38% used the Ukrainian language. From time to time, Ukrainian groups would visit Siberia. Nonetheless most of the Ukrainians did assimilate.

In Eastern Europe, the Ukrainian diaspora can be divided as follows:

- In Poland: 200-300 thousand Ukrainians

- In Czechoslovakia: 120-150 thousand Ukrainians

- In Romania: 100-150 thousand Ukrainians

- In Yugoslavia: 45-50 thousand Ukrainians.

In all these countries, Ukrainians had the status of a minority nation with their own socio-cultural organisations, schools, and press. The degree of these rights varied from country to country. They were greatest in Yugoslavia.

The largest Ukrainian diaspora was in Poland. It consisted of those Ukrainians, which were left in the western parts of Galicia that after the Second World War remained in Poland and had not emigrated to the Ukrainian SSR or resettled, and those who were resettled to the western and northern parts of Poland, which before the Second World War had been part of Germany.

Ukrainians in Czechoslovakia lived in the Prešov Region, which can be considered Ukrainian ethnographic territory, and had substantial rights. The Ukrainians in the Prešov Region had their own church organisation.

Ukrainians in Romania lived in the Romanian parts of Bukovina and the Maramureş Region, as well as in scattered settlements throughout Romania.

Ukrainians in Yugoslavia lived primarily in Bancka and Srem regions of Vojvodina and Bosnia. These Ukrainians had their own church organisation as the Eparchy of Križevci.

Size

Of the countries where the Ukrainian diaspora had settled, only in Canada and the Soviet Union were information about ethnic background collected. However, the data from the Soviet Union is suspect and underestimates the number of Ukrainians. In 1970, the Ukrainian diaspora can be given as follows:

- In the Soviet Union: officially 5.1 million Ukrainians

- In the European part: 2.8 million Ukrainians

- In the Asian part: 2.3 million Ukrainians

- In Eastern Europe (outside of the Soviet Union): 465-650 thousand Ukrainians

- In Czechoslovakia: 120-150 thousand Ukrainians

- In Poland: 200-300 thousand Ukrainians

- In Romania: 100-150 thousand Ukrainians

- In Yugoslavia: 45-50 thousand Ukrainians

- In Central and Eastern Europe: 88-107 thousand Ukrainians

- In Austria: 4-5 thousand Ukrainians

- In Germany: 20-25 thousand Ukrainians

- In France: 30-35 thousand Ukrainians

- In Belgium: 3-5 thousand Ukrainians

- In the United Kingdom: 50-100 thousand Ukrainians

- In the Americas and Australia: 2,181-2,451 thousand Ukrainians:

- In the USA: 1,250-1,500 thousand Ukrainians

- In Canada: 581 thousand Ukrainians

- In Brazil: 120 thousand Ukrainians

- In Argentina: 180-200 thousand Ukrainians

- In Paraguay: 10 thousand Ukrainians

- In Uruguay: 8 thousand Ukrainians

- In other American countries: 2 thousand Ukrainians

- In Australia and New Zealand: 30 thousand Ukrainians.

For the Soviet Union, it can be assumed that about 10-12 million people of Ukrainian (7-9 million in Asia) heritage live outside the Ukrainian SSR.

After 1991

After the independence of Ukraine, many Ukrainians have emigrated to Portugal, Spain, the Czech Republic, Russia, and Italy due to the uncertain economic and political situation at home.

Many Ukrainians live in Russia either along the Ukrainian border or in Siberia. In 1990s, the number of Ukrainians living in the Russian Federation was calculated to be around 5 million.[3] These regions, where Ukrainians live, can be subdivided into 2 categories: Regions along the mixed Ukrainian-Russian border territory and The Far East territory:

- The northern part of Sloboda Ukraine where Ukrainians have been living for centuries

- Siberian Ukrainians, Descendents of the Ukrainians deported to Siberia during the Stalin era

- The rest of Russia, formed from systematic migration since the start of the 19th century.

Ukrainians can also be found in parts of Romanian and Slovakia that border Ukraine.

The size of the Ukrainian diaspora has changed over time due to the following factors:

- Growth Factors

- New emigration from Ukraine

- Natural Growth

- Decrease Factors

- Returning of emigrants to Ukraine

- Assimilation

In 2004, the Ukrainian diaspora was distributed as follows:

| Country | Number (thousands) | Main Areas of Settlement |

| Russia | 2.942-4.379[4][5][6] | In the regions of Kursk, Voronezh, Saratov, Samara, Astrakhan, Vladivostok and the Don River. From Orenburg to the Pacific Ocean, in the Primorsky Krai along the Ussuri River, and in the Amur Oblast ("Zeleny Klyn") Norilsk, Magadan, Yakutia and Vorkuta |

| Kazakhstan | 896.2-2,400 | In the north and urban areas |

| USA | 900 | States: Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Ohio, Illinois, Michigan, Minnesota, Maryland, Florida, California, Texas, and Wisconsin |

| Canada | 1,000 | Provinces: Ontario, Alberta, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Quebec, and British Columbia |

| Brazil | 1,000 | States: Paraná, São Paulo, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande do Sul |

| Moldova | 600.4-650 | Transnistria, Chişinău |

| Poland | 360-500 [27 (census 2002)] | Regions: Western and northern parts of Poland (voivoideships of Olsztyn, Szczecin, Wrocław, Gdańsk, and Poznań) |

| Greece | 350-360 | Regions: Northern Greece, Thessaloniki, Athens |

| Italy | 320-350 | Regions: North Italy, Naples, Sicily |

| Belarus | 291-500 | Brest Oblast |

| Argentina | 100-250 | Provinces: Buenos Aires, Misiones, Chaco, Mendoza, Formosa, Córdoba, and Río Negro |

| Uzbekistan | 153.2 | Urban Centres |

| Kyrgyzstan | 108 | Urban Centres |

| Paraguay | 102 | Regions: in the area of Colonia Fram, Sandov, Nuevo Volyn, Bohdanivky, and Tarasivky |

| Slovakia | 40-100 | Regions: Eastern Slovakia, Prešov |

| Latvia | 92 | Urban Centres |

| Romania | 61-90[7] | Regions: Southern Bukovina (Suceava region), Maramureş region, Banat, and Northern Dobruja |

| former Yugoslavia | 60 | Regions: Vojvodina (Backa Region), Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Croatia (Slavonia) |

| Portugal | 40-150 | Lisbon and surroundings, interior of the country |

| Georgia | 52.4 | Urban Centres |

| Czech Republic | 50 | Sudetenland |

| Estonia | 48 | Urban Centres |

| Lithuania | 44 | Urban Centres |

| Turkmenistan | 35.6 | Urban Centres |

| France | 35 | Regions: Central, Eastern, Southwestern, and Northwestern France |

| United Kingdom | 35 | Counties: Greater London, Lancashire, Yorkshire, as well as Central and Northern England and Scotland |

| Australia | 35 | States/territories: New South Wales, Victoria, Western Australia, South Australia, Queensland and ACT |

| Azerbaijan | 32.3 | Urban Centres |

| Germany | 22 | States: Bavaria, Baden-Württemberg, Hesse, North Rhine-Westphalia, and Lower Saxony |

| Uruguay | 10 | Regions: Montevideo, San José, and Paysandú |

| Armenia | 8.3 | Urban Centres |

| Austria | 9-10 | Region: Vienna and surroundings |

| Bulgaria | 5-6 | Region: Sofia, Plovdiv, Dobrich and other big cities in Bulgaria |

| Belgium | 5 | Region: Central and Eastern Belgium |

| Hungary | 3 | Region: The Tysa River Basin |

| Venezuela | 3 | Region: Caracas, Valencia, Maracan |

| New Zealand | 2 | Regions: Christchurch, Auckland, Wellington |

| Chile | 1.0-1.5? | Region: Santiago, Chile |

| Netherlands | 0.6 | Region: on the border with Germany |

See also

- Ukrainian World Congress

- Shevchenko Scientific Society

- Ukrainians

- Ukrainian Village, Chicago

- Ukrainian Association of Washington State

- Ukrainians of Argentina

- Ukrainians in Siberia

- Ukrainians in Portugal

- Ukrainians in Kuban

- Ukrainians in Russia

- Ukrainian Institute in London

Notes

- ↑ Christopher Gilley, The 'Change in Signposts' in the Ukrainian Emigration. A Contribution to the History of Sovietophilism in the 1920s, Stuttgart: Ibidem, 2009

- ↑ John Kolasky, The Shattered Illusion. The History of Ukrainian Pro-Communist Organizations in Canada, Toronto: PMA Books

- ↑ Democratic Changes and Authoritarian Reactions in Russia, Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova By Karen Dawisha, Bruce Parrott. Cambridge University Press, 1997 ISBN 0-521-59732-3, ISBN 978-0-521-59732-6. p. 332

- ↑ "Government portal :: Ukrainian Diaspora". kmu.gov.ua. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ↑ Загальна чисельність українців у Росії становить 4 379 690 осіб.

- ↑ "Ukraine : :". culturalpolicies.net. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ↑ Romanian National Institute of Statistics, 2002 census, "Populaţia după etnie"

References

- Based on the August 17, 2006 Ukrainian version of the article

- L Y Luciuk, Searching for Place: Ukrainian Displaced Persons, Canada and the Migration of Memory University of Toronto Press, 2001

- Ukraine: A Concise Encyclopaedia. - Toronto, 1971

- (Ukrainian) Український Науковий Ін-т Гарвардського Ун-ту. Українці в американському та канадійському суспільствах. Соціологічний збірник, за ред. В.Ісаєва. - Cambridge, 1976

- (Russian) Томилов И. Современные этнические процессы в южных и центральных зонах Сибири. // Советская Этнография, 4, 1978

- (Ukrainian) Кубійович В. Укр. діяспора в СССР в світлі переписів населення // Сучасність, ч. (210). - Munich, 1978

- (Ukrainian) Енциклопедія українознавства

- Ukrainian Otherlands. Diaspora, Homeland, and Folk Imagination in the Twentieth Century by Natalia Khanenko-Friesen. 2015. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. 290 pages. ISBN 978-0-299-30344-0

- https://muse.jhu.edu/book/40918

- http://www.indiana.edu/~jfr/review.php?id=1941

Online references

- "Ukrainians abroad have a more developed sense of patriotism..." Zerkalo Nedeli (the Mirror Weekly), November 27 - December 3, 2004. Available online in Russian and in Ukrainian.

* - Ukrainian diaspora in Canada and U.S.

- Україна та українське зарубіжжя

- Encyclopedia of Ukraine

- http://www.kobza.com.ua

- http://ukrainianworldcongress.org

- Українці за кордоном

- Чисельність українців в США

- Оціночна чисельність українців по країнах світу і перелік мережевих майданів зарубіжжя

- -Українці в США - Ukrainians in USA

- -Українці в Нью-Йорку - Ukrainians in New York

- - The Association of Ukrainians in Great Britain, Edinburgh Branch

- - Ukrainians in Bulgaria

- - "Byku" - Youth Club of the Ukrainians in Bulgaria

- - Ukrainian Institute in London

- - Ukrainian Genealogical Research Bureau

- Ukrainian Genealogy and Family History | Library and Archives Canada

- Suggested List of Sources for the Study of Ukrainian Family History