United States Marine Corps Women's Reserve

The United States Marine Corps Women's Reserve (MCWR) was the World War II women's branch of the US Marine Corps Reserve. It was authorized by the U.S. Congress and signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt 30 July 1942. Yet, the Marine Corps delayed the formation of the MCWR until 13 February 1943. This law allowed for the acceptance of women into the reserve as commissioned officers and at the enlisted level, effective for the duration of the war plus six months. The purpose of the law was to release officers and men for combat and to replace them with women in the shore stations. Ruth Cheney Streeter was appointed the first director of the MCWR. She was sworn in with the rank of major and later was promoted to a full colonel. Streeter attended Bryn Mawr College and had been involved in health and welfare work. The MCWR did not have an official nickname, as did the other World War II women's military services.

Background

At the out-break of World War II, the notion of women serving in the Navy or Marine Corps (both were under the jurisdiction of the Department of the Navy) was not widely supported by the congress or by the branches of the military services. Nevertheless, there were some who believed that women would eventually be needed in the military. The most notable was Edith Nourse Rogers, Representative of Massachusetts, and Eleanor Roosevelt, wife of the president, who helped pave the way for its reality. When President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed what would become Public Law 689 on 30 July 1942, it established a Women’s Reserve as a branch of the Naval Reserve for the Navy and Marine Corps.[1] The idea behind the law was to free-up officers and men for combat, with women standing-in for them at shore stations on the home front. Women could now serve in the MCWR as an officer or at an enlisted level, with a rank or rating consistent with that of men. MCWR volunteers could only serve for the duration of the war, plus six months.[2] But the Corps saw fit to delay formation of the MCWR until 13 February 1943.[3] It was the last service branch to accept women into its ranks, and “there was considerable unhappiness about making the Marine Corps anything but a club for white men”.[4] In fact, General Thomas Holcomb, Commandant of the Marine Corps was a well-known opponent of women serving in the corps.[5] But he later reversed himself, saying, “there’s hardly any work at our Marine stations that women can’t do as well as men. They do some work far better than men. … What is more, they’re real Marines. They don’t have a nickname, and they don’t need one.”[6] Holcomb rejected all acronyms or monikers for the MCWR; he did not believe they were compulsorily. And there were many of them, including: Femarines, WAMS, Dainty Devil-Dogs, Glamarines, Women’s Leatherneck-Aides, MARS, and Sub-Marines. By the summer of 1943, attempts to pressure the MCWR into a nickname had diminished. WRs was as far as Holcomb and Streeter would move in that direction.[7]

Mrs. Ruth Cheney Streeter was named the first director of the MCWR; commissioned a major and sworn in by the Secretary of the Navy on 29, January 1943. She was not the first woman to see active duty in the Marine Corps during World War II. Weeks earlier, Mrs. Anne A. Lentz, a civilian clothing expert who had helped design the MCWR uniforms, was commissioned a captain. Lentz came to the corps on a 30-day assignment from the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) and stayed on.[8] Streeter was born in Brookline, Massachusetts, in 1895[9] and attended Bryn Mawr College for two years. She was the wife of a prominent (Morristown, NJ) lawyer and businessman, and the mother of four children; three sons in the military in World War II and a younger daughter. Although Streeter had 20 years of active civic work, she had never held a paying job. She was selected from a field of 12 outstanding women, all recommended to the corps by Dean Virigina C. Gildersleeve of Barnard College, who had earlier recommended Mildred McAfee for the director of the WAVES, Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Services. Streeter was 47 years of age when selected to head the MCWR. She was described as confident, spirited, patriotic, and a principled person, qualities she demonstrateed. In 1940, she believed the United States would be drawn into World War II. Intending to be part of the war effort, Streeter learned to fly, earned a commercial pilots license and bought a small airplane. And in the summer of 1941, she joined the Civil Air Patrol. Although her plane was used to fly missions, she was, unhappily, relegated to doing … “all the dirty work’’. Then, when the Women’s Air Service Pilots (WASP) was formed, Streeter was 12 years over the age limit, but applied five times and was rejected five times. In January 1943, she inquired about service with the WAVES, flying was out of the question but told she could be a ground instructor. Streeter turned it down, and a month later became the director of the MCWR.[10]

Recruiting

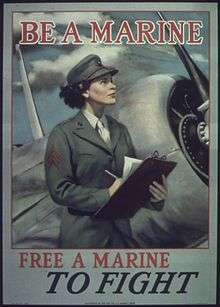

The slogan "Free a Marine to Fight" proved to be a strong drawing card for the MCWR, stronger than any tailored by the WAC, Waves, or SPARS.[11]

Training

Initially, the Marine Corps relied upon the Navy's training facilities for both its officers and its enlisted women. Classes began in March 1943 for both officer candidates and recruits. The first group of women officers received direct commissions, based on their ability, education, and civilian expertise. On 13 March 1943, just one month after the Marine Corps began accepting women, the first class of officer candidates began training at Mount Holyoke College in South Hadley, Massachusetts. The first class of recruits (722) completed their recruit training at Hunter College in The Bronx, New York. In July 1943, the Marine Corps transferred the officer and recruit training to more permanent facilities in New River, North Carolina. Nearly 19,000 women would complete their training at New River during the course of the war.

Assignments

The women were assigned to over 200 different jobs, among them: radio operator, photographer, parachute rigger, driver, aerial gunnery instructor, cook, baker, quartermaster, control tower operator, motion picture operator, auto mechanic, telegraph operator, cryptographer, laundry operator, post exchange manager, stenographer, and agriculturist. They would serve as the trained nucleus for possible mobilization emergencies. The demobilization of the Marine Corps Women's Reserve of 820 officers and 17,640 enlisted was to be completed by 1 September 1946. Of the 20,000 women who had joined the Marine Corps during World War II, only 1,000 remained in the Marine Corps Women's Reserve on 1 July 1946.

On 12 June 1948, the United States Congress passed the Women's Armed Services Integration Act, and made women a permanent part of the regular Marine Corps.

In 1950, the Women Marine Corps Reserves mobilized for the Korean War and 2,787 women were called to active duty. By the height of the Vietnam War, about 2,700 women had served both stateside and overseas. By 1975, the Marine Corps had approved the assignment of women to all occupational fields, except the infantry, artillery, armor, and pilot-air crew. Over 1,000 women were deployed in Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm in 1990–1991.

Chronology

- 1943—Private Lucille McClarren, first enlisted woman

- 1945—First detachment of women Marines arrives in Hawaii for duty.

- 1947—First female warrant officer in the Corps — Lotus Mort

- 1948 – President Harry Truman signs Public Law 625 (the Women's Armed Services Integration Act) on June 30, 1948. It incorporates the women's service organizations, like the Marine Corps Women's Reserve, into the regular military on a permanent basis. Colonel Katherine A. Towle was declared the first Director of Women Marines.

- 1948 – First group of women sworn into the regular Marine Corps.

- 1960 – First woman Marine is promoted to E-9 — Master Gunnery Sergeant, Geraldine M. Moran.

- 1961 – The first woman Marine is promoted to Sergeant Major (E-9) — Bertha Peters Billeb.

See also

- Minnie Spotted-Wolf, first Native American woman to enlist in the Marine Corps, enlisted in USMCWR in 1943

- Women in the United States Marines

References

Citations

Bibliography

- National Archives and Records Administration, Paula Nassen Pouls, Editor. (1996). A Women's War Too: U.S. Women in the military in World War II. United States: National Archives Tust Fund Board. ISBN 1-880875-098.

- Ebert and Hall, Jean and Marie-Beth (1993). Crossed Currents. McLean, VA: Brassey's. ISBN 0-02-881022-8.

- Soderbergh, Peter, A. (1992). Women Marines: The World War II Era. westport, CT: Praeer Publishers. ISBN 0-275-94131-0.

- Stremlow, Colonel Mary V., USMCR (Ret). (1994). Free a Marine toFight: Women Marines in World War II. Washington, DC: Marine Corps Historical Center.

Further reading

- Litoff, Judy Barrett, and David C. Smith. "The Wartime History of the Waves, SPARS, Women Marines, Army and Navy Nurses, and WASP's.

External links

![]() Media related to United States Marine Corps Women's Reserve at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to United States Marine Corps Women's Reserve at Wikimedia Commons

- Navy & Marine Corps World War II Commemorative Committee. "Article: Women in the Marine Corps". Archived from the original on 2006-05-06. Retrieved 2006-01-11.

- USMCWR history and WWII women's uniforms in color — World War II US women's service organizations (WAC, WAVES, ANC, NNC, USMCWR, PHS, SPARS, ARC and WASP).