Ural (region)

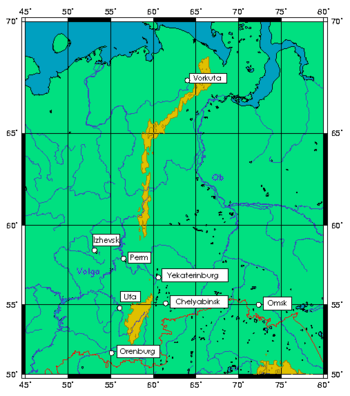

The Urals (Russian: Ура́л) are a geographical region located around the Ural Mountains, between the East European and West Siberian plains. It extends approximately from north to south, from the Arctic Ocean to the bend of Ural River near Orsk city. The boundary between Europe and Asia runs along the eastern side of the Ural Mountains.[3] Ural mostly lies within Russia but also includes a part of northwestern Kazakhstan. This is a historical, not an official entity, with the boundaries overlapping its western Volga and eastern Siberia neighbor regions. At points in time, parts of the Urals were considered a gateway to Siberia, if not Siberia itself, or were combined with the Volga administrative divisions. At present time, there are two official namesake entities, the Ural Federal District and the Ural economic region. While the latter follows the historical boundaries, the former is a political product; the District omits Western Urals and includes Western Siberia instead.

The historical center of the Urals is Cherdyn, nowadays it is the small town in Perm Krai. Perm was an administrative center of the gubernia with the same name by 1797. The most territory of historical and modern Ural was included in Perm gubernia. The administrative center of Urals was moved to Sverdlovsk (nowadays Yekaterinburg) after Revolution and Civil war. Nowadays Ural economic region does not have an administrative and informal capital, whereas Yekaterinburg is administrative center of the Ural Federal District.[1]

Etymology

From the 11th century, the region of the Ural Mountains was called "stone" by Russians. In the mid-16th – early 17th century, the southern parts became known as Ural, which later spread to the entire area. The name probably originated from Turkic "aral". This word literally means "island" and was used for any territory different from the surrounding terrain. In Bashkortostan there is a 13th-century legend about a hero named Ural. He sacrificed his life for the sake of his people, and they poured a stone pile over his grave, which later turned into the Ural Mountains.[3]

Topography

.jpg)

By topography and other natural features, Ural is divided, from north to south, into the Polar (or Arctic), Near-Polar (or Sub-Arctic), Northern, Central and Southern parts. The Polar Ural has an area of about 25,000 km2 and a strongly dissected relief. The Near-Polar Ural is wider (up to 150 km) and higher than the Polar Ural. The Northern Ural consists of a series of parallel ridges with the height up to 1,000–1,300 m and longitudinal depressions, which are elongated from north to south. The Central Ural is the lowest part of Urals, with the highest mountain of 994 m (Basegi) and a smooth relief. The relief of Southern Ural is more complex, with numerous valleys and ridges directed south-west and meridionally.[3][4]

Geology

Urals contains 48 species of economically valuable ores and minerals. Eastern regions are rich in chalcopyrite, nickel oxide, chromite and magnetite ores, as well as in coal (Chelyabinsk Oblast), bauxite, gold and platinum. Western Ural contains deposits of coal, oil, gas and potassium salts. The specialty of Urals is precious and semi-precious stones, such as emerald, amethyst, aquamarine, jasper, rhodonite, malachite and diamond.[3]

Climate

The climate of Ural is continental. The ridges of the Ural Mountains are elongated from north to south, they effectively absorb sunlight thereby increasing the temperature. The areas west to the Ural Mountains are 1–2 °C warmer in winter than the eastern regions because the former are warmed by the Atlantic winds whereas the eastern slopes are chilled by the Siberian air masses. The average January temperatures increase in the western areas from –20 °C in the Polar to –15 °C in the Southern Urals and the corresponding temperatures in July are 10 °C and 20 °C. The western areas also received more rainfall than the eastern ones by 150–300 mm per year. The highest precipitation (1000 mm) is in the Northern Ural that causes the average height of snow up to 90 cm. The eastern parts receive from 500–600 mm on the north to 300–400 mm on the south.[3]

Rivers and lakes

Most Ural rivers belong to the basin of the Arctic Ocean. They include Tobol, Iset, Tura, Pechora, Lozva and Severnaya Sosva Rivers. The southern rivers – Ural, Kama, Belaya and Chusovaya Rivers – belong to the Caspian Sea basin. Western rivers, especially north-western ones, are more affluent. They have high and long (2–3 months) floods in May–June (June–July in the Polar Ural). The south-eastern rivers are much narrower and may dry up in summer. Rivers are fed by melting snow and precipitations. The largest lakes are on the east of the Central and Southern Urals. They include Tawatui, Argazi, Uvildy and Turgoyak. The deepest lake (136 m) is Bolshoe Schuchye. Rivers and lakes are used as a water supply, transport routes and for waterlogging. Some rivers have dams forming the Kama and Votkinsk Reservoirs.[3][4]

Flora

The landscapes of Urals change both in the latitudinal and vertical directions and are dominated by steppes and forests. Steppes lie mostly in the southern and especially south-eastern Urals. Meadow steppes have developed in the lower parts of mountain slopes and are covered with various clovers, daisies, filipendula, meadow-grass and foxtail millet, reaching the height of 60–80 cm. Many lands are cultivated. Moving to the south, the meadow steppes become more sparse, dry and low. The steep gravelly slopes of mountains and hills of eastern slopes of the Southern Ural are mostly covered with rocky steppes. Valleys of the rivers contain willow, poplar and caragana shrubs.[3]

Forest landscapes of Urals are diverse, especially the southern part. The western areas are dominated by dark coniferous taiga forests which change to mixed and deciduous forests on the south. The eastern mountain slopes have light coniferous taiga forests. Southern Ural is most diverse in the forest composition; here together with coniferous forests also abundant are other tree species such as larch, oak, birch, maple and elm. The Northern Ural is dominated by Siberian species of fir, cedar, spruce and pine. Forests are much more sparse in Polar Ural. Whereas in other Ural Mountains areas they grow up to the heights of 1 km, the forests cease at 250–400 m in the Polar Urals. The polar forests are low and are mixed with swamps, lichens, bogs and shrubs. Abundant are dwarf birch, mosses and berries (blueberry, cloudberry, black crowberry, etc.).[3]

Fauna

Ural forests are inhabited by animals typical of Siberia, such as elk, brown bear, fox, wolf, wolverine, lynx, squirrel and sable (north only). In the Central Ural, one can meet a rare mixture of sable and pine marten named kidus. In the Southern Ural frequent are badger and black polecat. Reptiles and amphibians live mostly in the Southern and Central Ural and are represented by the common viper, lizards and grass snakes. Bird species are represented by capercaillie, black grouse, hazel grouse, spotted nutcracker and cuckoos. In the summer, South and Central Urals are visited by songbirds, such as nightingale and redstart.[3][4]

Steppes of the Southern Urals are dominated by hares and rodents such as gophers, susliks and jerboa. There are many birds of prey such as lesser kestrel and buzzards. The animals of the Polar Ural are characteristic of the tundra and include fox, lemming and reindeer. The birds of those areas include rough-legged buzzard, snowy owl and rock ptarmigan.[3][4]

Astronomical events

2013 Russian meteor event

At around 9:20 a.m. on Friday, February 15, 2013, an astronomical incident occurred, known as the 2013 Russian meteor event. A fiery meteor, roughly 55 feet wide, weighing at least 10,000 tons and traveling at a speed of 30,000 miles per hour, burst through earth's atmosphere over the Ural Mountains. The news media reported that the meteor's deafening shock wave packed the punch of a 500-kiloton explosion, and was so powerful that it shattered windows and collapsed walls, damaging 4,000 buildings and injuring 1,491 people, the majority of whom were caught in the shards of flying glass. Of the people injured, 311 were children who were at school at the time. Small rocky meteorite fragments were discovered near an eight-metre crater, believed to have been created by the impact, in an ice-covered reservoir near the town of Chebarkul. The overall resulting damage from the shock wave was estimated at $33,000,000.

History

The first people appeared on the Ural at the end of the Early Paleolithic period (about 75 thousand years ago). Several sites were discovered from the late Paleolithic (35–10 thousand years ago) including the Kapova Cave. In the Neolithic period, tribes have formed which became the basis of the Uralic language community, and mixed (Mongoloid, europoid) anthropological type. Around the same time, farming and animal husbandry develop in the Southern Ural. Manufacture of copper and bronze started in the early 2nd millennium BC and production of iron was developed around the 8th–7th centuries BC.[3]

At the beginning of the 2nd millennium, the primitive society of Ural started transforming to feudal relations. Around the 14th century, the feudal state Great Perm was created west to the Northern Ural. Russian started moving to Ural in the 11th century, mostly from the Novgorod areas. They became active around the 14th century when a number of settlements were established in the Northern Ural and attributed to Veliky Novgorod. Their ownership went to the Moscow state in 1471, together with lands around the Kama River. After the defeat of Khanate of Kazan in 1552, the Russian influence expanded to the most parts of Bashkortostan and Udmurtia.[3]

In the 17th century, Ural became inhabited by Slavs who brought advanced farming technique and craftsmanship. This changed the lifestyle of the area and quenches the past armed conflicts. Grain-based agriculture, small-scale industries (wood, leather, pottery, blacksmithing, etc.) and a network of markets spread over Ural. The salt industry was developed in Solikamsk. At the same time, the national and social oppression started of the indigenous people of the area, such as Mansi, Khanty and Bashkirs.[3]

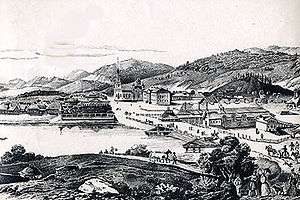

In the 17th century rich and high-quality mineral deposits were discovered in the Ural region. First iron and copper smelters were founded by the mid-17th century. The area was recognized by the Russian government as a strategic source of raw materials. More than 60 factories were built in the first half of the 18th century and this number doubled in the 1750–60s. The industrial activity declined in the early 19th century due to the crisis of the feudal system in Russia, and the growth slowed down in all areas except for the gold mining. The largest industrial and commercial centers were Perm, Yekaterinburg, Orenburg, Ufa, Kungur and Irbit. Irbit hosted the biggest fair of the Urals. In the 1840s, regular commercial navigation started on the Kama River.[3]

As a result of the Emancipation reform of 1861, most Ural farmers lost more than half of their personal lands. First joint-stock companies appeared on the Ural in the second half of the 19th century, including those with foreign capital. Many old ironworks were reconstructed and a number of new ones were built. The development accelerated not only in the traditional gold and platinum industries, but also in the coal mining and engineering. Mechanical factories were established in Yekaterinburg, Perm, Izhevsk and others cities, and chemical industry was developed in Berezniki. Nevertheless, Ural lost its status of the main metallurgical area to the South of Russia. The end of 19th century saw a rapid growth of the Ural cities and of the anti-capitalist movements. The long-term exploitation of the factory workers resulted in establishment of Social Democratic committees demanding improvements of working conditions. Those activities peaked around the period of the political collapse of the 1910s in Russia. This brought a severe industrial crisis, fuel shortages, disruption of transport, reduction of agricultural production and the deterioration of the life conditions. The October Revolution brought numerous benefits to the workers, but was followed by the years of Civil Wars (1917–19). The situation improved only after 1920. In 1920–21, the industrial production was at the 12% level of that in 1913, but by 1925–26 it recovered to 93% and in 1937 reached 700%. New giant plants were raised in Magnitogorsk (1932, iron and steel production), Bereznikovskiy (1932, Chemistry), Sverdlovsk (1933, Heavy Machinery), Chelyabinsk (1933, tractors), Solikamsk (1934, potassium), Krasnokamsk (1936, pulp and paper), Novotagilsk (metallurgy) and others. In 1929, oil was discovered in the Kama River basin and its production began in 1932 in Bashkortostan.[3]

During World War II (1941–45) Ural became the industrial backbone of Russia as most important industrial enterprises were evacuated there from the western Russia occupied by Germans. From the summer to winter of 1941, 667 factories were moved to Ural and by the end of 1941 Ural accounted for 62% of the Soviet iron production. The Ural's industrial production increased 3 times in 1943 relatively to 1941 and the military production increased 6 times. During the war, Ural accounted for 40% of the Soviet military production. Three Ural's plants gave 66% of Soviet tanks and mobile artillery units. The annual increase of production was about 50%. In 1946, most plants were converted into non-military directions.[3]

Ethnic composition

The Northern Urals is home to Uralic speaking people like Udmurts, Mari, Komi, Mansi and Khanty people. The indigenous population of the Polar Urals consists of the Nenets and Samoyedic peoples who are widespread through the Siberia and have their own languages. Bashkirs form the largest indigenous group of the region. They live in the Southern Ural and speak a language of the Turkic group. Kazakhs are another significant national fraction of the Southern Ural. Many northern tribals still continue their traditional activities, including fishing, hunting and animal husbandry (reindeer). The nomadic people of the south used to breed horses, but are mostly settled now and are involved in agriculture, especially growth of wheat, potato, melons and watermelons. The majority of the Urals population (about 80%) is however Russians, who are mostly concentrated in the cities of the Central and Southern Urals and are involved in the industry.[4]

Current administrative divisions of Urals

| Subdivision (major city) | Economic region[2] | Federal District[1] |

|---|---|---|

| Bashkortostan Republic (Ufa) | Ural | Volga |

| Chelyabinsk Oblast (Chelyabinsk) | Ural | Ural |

| Kurgan Oblast (Kurgan) | Ural | Ural |

| Orenburg Oblast (Orenburg) | Ural | Volga |

| Perm Krai (Perm) | Ural | Volga |

| Sverdlovsk Oblast (Yekaterinburg) | Ural | Ural |

| Tyumen Oblast (Tyumen) | West Siberia | Ural |

| Khanty–Mansi Autonomous Okrug (Khanty-Mansiysk) | West Siberia | Ural |

| Yamalo-Nenets Autonomous Okrug (Salekhard) | West Siberia | Ural |

| Udmurt Republic (Izhevsk) | Ural | Volga |

| Aktobe Province (Aktobe) | n/a | n/a |

The table (see also maps above) reveals that the Ural Federal District and Ural economical region are rather different entities, which geographically differ from the Urals, even though the Urals is not well defined geographically. In particular, those entities include parts of Volga and Siberia, and do not include areas belonging to Kazakhstan. Meanwhile, the southern part of the Ural Mountains (including Mugodzhar Mountains) does belong to Kazakhstan.[4]

See also

- Ural Cossacks

- Ural Ocean

- Ural pictograms

- Uralic languages

- History of Ural

References

- 1 2 3 "Указ Президента РФ от 13 мая 2000 г. N 849 "О полномочном представителе Президента Российской Федерации в федеральном округе" (Decree No 849 by the President of Russia on 13 May 2000)" (in Russian).

- 1 2 "Ural economic region" (in Russian). Great Soviet Encyclopedia.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 "Ural (geographical)". Great Soviet Encyclopedia.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ural Mountains, Encyclopædia Britannica on-line

Coordinates: 60°00′N 60°00′E / 60.000°N 60.000°E