Uralic languages

| Uralic | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution: | Central, Eastern, and Northern Europe, North Asia |

| Linguistic classification: | One of the world's primary language families |

| Proto-language: | Proto-Uralic |

| Subdivisions: | |

| ISO 639-5: | urj |

| Glottolog: | ural1272[1] |

|

Geographical distribution of the Uralic languages | |

The Uralic languages /jʊˈrælᵻk/ (sometimes called Uralian languages /jʊˈreɪliən/) constitute a language family of some 38[2] languages spoken by approximately 25 million people, predominantly in Northern Eurasia. The Uralic languages with the most native speakers are Hungarian, Finnish, and Estonian, which are official languages of Hungary, Finland, and Estonia, respectively, and of the European Union. Other Uralic languages with significant numbers of speakers are Erzya, Moksha, Mari, Udmurt, and Komi, which are officially recognized languages in various regions of Russia.

The name "Uralic" derives from the fact that areas where the languages are spoken spread on both sides of the Ural Mountains. Also, the original homeland (Urheimat) is commonly hypothesized to lie in the vicinity of the Urals.

Finno-Ugric is sometimes used as a synonym for Uralic, though Finno-Ugric is widely understood to exclude the Samoyedic languages.[3] Scholars who do not accept the traditional notion that Samoyedic split first from the rest of the Uralic family, such as Tapani Salminen, may treat both terms as synonymous.

History

Homeland

In recent times, linguists often place the Urheimat (original homeland) of the Proto-Uralic language in the vicinity of the Volga River, west of the Urals, close to the Urheimat of the Indo-European languages, or to the east and southeast of the Urals. Gyula László places its origin in the forest zone between the Oka River and central Poland. E. N. Setälä and M. Zsirai place it between the Volga and Kama Rivers. According to E. Itkonen, the ancestral area extended to the Baltic Sea. P. Hajdu has suggested a homeland in western and northwestern Siberia.[4]

Early attestations

The first plausible mention of a Uralic people is in Tacitus's Germania (c. 98 AD),[5] mentioning the Fenni (usually interpreted as referring to the Sami) and two other possibly Uralic tribes living in the farthest reaches of Scandinavia. There are many possible earlier mentions, including the Irycae (perhaps related to Yugra) described by Herodotus living in what is now European Russia, and the Budini, described by Herodotus as notably red-haired (a characteristic feature of the Udmurts) and living in northeast Ukraine and/or adjacent parts of Russia. In the late 15th century, European scholars noted the resemblance of the names Hungaria and Yugria, the names of settlements east of the Ural. They assumed a connection but did not seek linguistic evidence.

Uralic studies

The affinity of Hungarian and Finnish was first proposed in the late 17th century. Two of the more important contributors were the German scholar Martin Vogel, who established several grammatical and lexical parallels between Finnish and Hungarian, and the Swedish scholar Georg Stiernhielm, who commented on the similarities of Sami, Estonian and Finnish, and also on a few similar words between Finnish and Hungarian.[6] These two authors were thus the first to outline what was to become the classification of the Finno-Ugric, and later Uralic family. This proposal received some of its initial impetus from the fact that these languages, unlike most of the other languages spoken in Europe, are not part of what is now known as the Indo-European family.

In 1717, Swedish professor Olof Rudbeck proposed about 100 etymologies connecting Finnish and Hungarian, of which about 40 are still considered valid.[7] In the same year, the German scholar Johann Georg von Eckhart, in an essay published in Leibniz's Collectanea Etymologica, proposed for the first time a relation to the Samoyedic languages.

Philip Johan von Strahlenberg in 1730 published his book Das Nord- und Ostliche Theil von Europa und Asia, surveying the geography, peoples and languages of Russia. All the main groups of the Uralic languages were already identified here.[8] Nonetheless, these relationships were not widely accepted. Hungarian intellectuals especially were not interested in the theory and preferred to assume connections with Turkic tribes, an attitude characterized by Ruhlen (1987) as due to "the wild unfettered Romanticism of the epoch". Still, in spite of this hostile climate, the Hungarian Jesuit János Sajnovics travelled with Maximilian Hell to survey the alleged relationship between Hungarian and Sami. Sajnovics published his results in 1770, arguing for a relationship based on several grammatical features.[9] In 1799, the Hungarian Sámuel Gyarmathi published the most complete work on Finno-Ugric to that date.[10]

At the beginning of the 19th century, research on this family was thus more advanced than Indo-European research. But the rise of Indo-European comparative linguistics absorbed so much attention and enthusiasm that Uralic linguistics was all but eclipsed in Europe; in Hungary, the only European country that would have had a vested interest in the family (Finland and Estonia being under Russian rule), the political climate was too hostile for the development of Uralic comparative linguistics.

Progress resumed after a number of decades with the first major field research expeditions on the Uralic languages spoken in the more eastern parts of Russia. These were made in the 1840s by Matthias Castrén (1813–1852) and Antal Reguly (1819–1858), who focused especially on the Samoyedic and the Ob-Ugric languages, respectively. Reguly's materials were worked on by the Hungarian linguist Pál Hunfalvy (1810–1891) and German Josef Budenz (1836–1892), who both supported the Uralic affinity of Hungarian.[11] Budenz was the first scholar to bring this result to popular consciousness in Hungary, and to attempt a reconstruction of the Proto-Finno-Ugric grammar and lexicon.[12] Another late-19th-century Hungarian contribution is that of Ignácz Halász (1855–1901), who published extensive comparative material of Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic in the 1890s,[13][14][15][16] and whose work is at the base of today's wide acceptance of the inclusion of Samoyedic as a part of Uralic.[17] Meanwhile, in the autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland, a chair for Finnish language and linguistics at the University of Helsinki was created in 1850, first held by Castrén.[18]

.svg.png)

In 1883 the Finno-Ugrian Society was founded in Helsinki on the proposal of Otto Donner, and during the late 19th and early 20th century (until the separation of Finland from Russia following the Russian revolution), a large number of stipendiates were sent by the Society to survey the less known Uralic languages. Major researchers of this period included Heikki Paasonen (studying especially the Mordvinic languages), Yrjö Wichmann (fi) (Permic), Artturi Kannisto (fi) (Mansi), Kustaa Fredrik Karjalainen (Khanty), Toivo Lehtisalo (Nenets), and Kai Donner (Kamass).[19] The vast amounts of data collected on these expeditions would provide edition work for later generations of Finnish Uralicists for more than a century.[20]

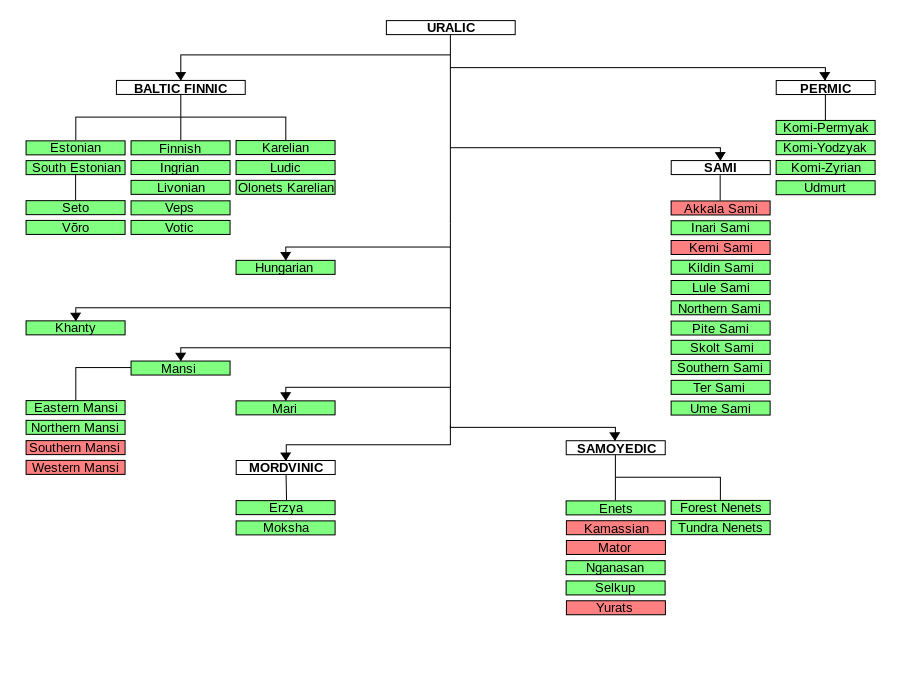

Classification

The Uralic family comprises nine undisputed groups with no consensus classification between them. (Some of the proposals are listed in the next section.) An agnostic approach treats them as separate branches.[21]

Obsolete or native names are displayed in italics.

- Finnic (Fennic, Baltic Finnic, Balto-Finnic, Balto-Fennic)

- Hungarian (Magyar)

- Khanty (Ostyak, Handi, Hantõ)

- Mansi (Vogul)

- Mari (Cheremis)

- Mordvinic (Mordvin, Mordvinian)

- Permic (Permian)

- Sami (Saami, Samic, Saamic, Lappic, Lappish)

- Samoyedic (Samoyed)

There is also historical evidence of a number of extinct languages of uncertain affiliation:

- Merya

- Muromian

- Meshcherian (until 16th century?)

Traces of Finno-Ugric substrata, especially in toponymy, in the northern part of European Russia have been proposed as evidence for even more extinct Uralic languages.[22]

Traditional classification

All Uralic languages are thought to have descended, through independent processes of language change, from Proto-Uralic. The internal structure of the Uralic family has been debated since the family was first proposed.[23] Doubts about the validity of most of the proposed higher-order branchings (grouping the nine undisputed families) are becoming more common.[23][24]

A traditional classification of the Uralic languages has existed since the late 19th century, tracing back to Donner (1879).[25] It has enjoyed frequent adaptation in whole or in part in encyclopedias, handbooks, and overviews of the Uralic family. Donner's model is as follows:

- Ugric (Ugrian)

- Finno-Permic (Permian-Finnic)

- Permic

- Finno-Volgaic (Finno-Cheremisic, Finno-Mari)

- Volga-Finnic

- Finno-Lappic (Finno-Saamic, Finno-Samic)

At Donner's time, the Samoyedic languages were still poorly known, and he was not able to address their position. As they became better known in the early 20th century, they were found to be quite divergent, and they were assumed to have separated already early on. The terminology adopted for this was "Uralic" for the entire family, "Finno-Ugric" for the non-Samoyedic languages (though "Finno-Ugric" has, to this day, remained in use also as a synonym for the whole family). Finno-Ugric and Samoyedic are listed in ISO 639-5 as primary branches of Uralic.

Nodes of the traditional family tree recognized in some overview sources:

| Source | Finno- Ugric | Ugric | Ob-Ugric | Finno- Permic | Finno- Volgaic | Volga- Finnic | Finno- Samic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Szinnyei (1910)[26] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| T. I. Itkonen (1921)[27] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Setälä (1926)[28] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Hajdú (1962)[29][30] | ✓ | ✗1 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗1 | ✗ |

| Collinder (1965)[31] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ |

| E. Itkonen (1966)[32] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Austerlitz (1968)[33] | ✗ 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ 2 | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Voegelin & Voegelin (1977)[34] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Kulonen (2002)[35] | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Lehtinen (2007)[36] | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Janhunen (2009)[37] | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

- Hajdú describes the Ugric and Volgaic groups as areal units.

- Austerlitz however accepts narrower-than-traditional Finno-Ugric and Finno-Permic groups that exclude Samic.

Little explicit evidence has however been presented in favor of Donner's model since his original proposal, and numerous alternate schemes have been proposed. Especially in Finland there has been a growing tendency to reject the Finno-Ugric intermediate protolanguage.[24][38] A recent competing proposal instead unites Ugric and Samoyedic in an "East Uralic" group for which shared innovations can be noted.[39]

The Finno-Permic grouping still holds some support, though the arrangement of its subgroups is a matter of some dispute. Mordvinic is commonly seen as particularly closely related to or part of Finno-Samic.[40] The term Volgaic (or Volga-Finnic) was used to denote a branch previously believed to include Mari, Mordvinic and a number of the extinct languages, but it is now obsolete[24] and considered a geographic classification rather than a linguistic one.

Within Ugric, uniting Mansi with Hungarian rather than Khanty has been a competing hypothesis to Ob-Ugric.

Lexical isoglosses

Lexicostatistics has been used in defense of the traditional family tree. A recent re-evaluation of the evidence[41] however fails to find support for Finno-Ugric and Ugric, suggesting four lexically distinct branches (Finno-Permic, Hungarian, Ob-Ugric and Samoyedic).

One alternate proposal for a family tree, with emphasis on the development of numerals, is as follows:[42]

- Uralic (*kektä "2", *wixti "5" / "10")

- Samoyedic (*op "1", *ketä "2", *näkur "3", *tettə "4", *səmpəleŋkə "5", *məktut "6", *sejtwə "7", *wiət "10")

- Finno-Ugric (*üki/*ükti "1", *kormi "3", *ńeljä "4", *wiiti "5", *kuuti "6", *luki "10")

- Mansic

- Mansi

- Hungarian (hét "7"; replacement egy "1")

- Finno-Khantic (reshaping *kolmi "3" on the analogy of "4")

- Khanty

- Finno-Permic (reshaping *kektä > *kakta)

- Permic

- Finno-Volgaic (*śećem "7")

- Mari

- Finno-Saamic (*kakteksa, *ükteksa "8, 9")

- Saamic

- Finno-Mordvinic (replacement *kümmen "10" (*luki- "to count", "to read out"))

- Mordvinic

- Finnic

- Mansic

Phonological isoglosses

Another proposed tree, more divergent from the standard, focusing on consonant isoglosses (which does not consider the position of the Samoyedic languages) is presented by Viitso (1997),[43] and refined in Viitso (2000):[44]

- Finno-Ugric

- Saamic–Fennic (consonant gradation)

- Saamic

- Fennic

- Eastern Finno-Ugric

- Mordva

- (node)

- Mari

- Permian–Ugric (*δ > *l)

- Permian

- Ugric (*s *š *ś > *ɬ *ɬ *s)

- Hungarian

- Khanty

- Mansi

- Saamic–Fennic (consonant gradation)

The grouping of the four bottom-level branches remains to some degree open to interpretation, with competing models of Finno-Saamic vs. Eastern Finno-Ugric (Mari, Mordvinic, Permic-Ugric; *k > ɣ between vowels, degemination of stops) and Finno-Volgaic (Finno-Saamic, Mari, Mordvinic; *δ́ > δ between vowels) vs. Permic-Ugric. Viitso finds no evidence for a Finno-Permic grouping.

Extending this approach to cover the Samoyedic languages suggests affinity with Ugric, resulting in the aforementioned East Uralic grouping, as it also shares the same sibilant developments. A further non-trivial Ugric-Samoyedic isogloss is the reduction *k, *x, *w > ɣ when before *i, and after a vowel (cf. *k > ɣ above), or adjacent to *t, *s, *š, or *ś.[39]

Finno-Ugric consonant developments after Viitso (2000); Samoyedic changes after Sammallahti (1988)

| Saamic | Finnic | Mordvinic | Mari | Permic | Hungarian | Mansi | Khanty | Samoyedic | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medial lenition of *k | no | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | |

| Medial lenition of *p, *t | no | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | no | no | |

| Degemination | no | no | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | |

| Consonant gradation | yes | yes | no | no | no | no | no | no | yes | |

| Development of | *δ | *δ | *t | *t | ∅ | *l | l | *l | *l | *r |

| *δ́ | *δ | *ĺ | ď ⟨gy⟩, j | *ĺ | *j | *j | ||||

| *s | *s | *s | *s | *š | *s | ∅ | *t | *ɬ | *t | |

| *š | *h | *š | *š | |||||||

| *ś | *ć | *s | *ś | *ś | s ⟨sz⟩ | *š | *s | *s | ||

| *ć | *ć | č ⟨cs⟩ | *ć ~ *š | *ć | ||||||

- Note: Proto-Khanty *ɬ in many of the dialects yields *t; it is assumed this also happened in Mansi and Samoyedic.

The inverse relationship between consonant gradation and medial lenition of stops (the pattern also continuing within the three families where gradation is found) is noted by Helimski (1995): an original allophonic gradation system between voiceless and voiced stops would have been easily disrupted by a spreading of voicing to previously unvoiced stops as well.[45]

Based on phonological isoglosses, Häkkinen (2007)[46] proposes the following tree:

- Uralic

- West Uralic

- Saamic

- Finnic

- Mordvinic

- Central Uralic (?)

- Mari

- Permic

- East Uralic

- Hungarian

- Ob-Ugric

- Mansi

- Khanty

- Samoyedic

- West Uralic

Typology

Structural characteristics generally said to be typical of Uralic languages include:

Grammar

- extensive use of independent suffixes (agglutination)

- a large set of grammatical cases marked with agglutinative suffixes (13–14 cases on average; mainly later developments: Proto-Uralic is reconstructed with 6 cases), e.g.:

- Erzya: 12 cases

- Estonian: 14 cases (15 cases with instructive)

- Finnish: 15 cases

- Hungarian: 18 cases (together 34 grammatical cases and case-like suffixes)

- Inari Sami: 9 cases

- Komi: in certain dialects as many as 27 cases

- Moksha: 13 cases

- Nenets: 7 cases

- North Sami: 6 cases

- Udmurt: 16 cases

- Veps: 24 cases

- unique Uralic case system, from which all modern Uralic languages derive their case systems.

- nominative singular has no case suffix.

- accusative and genitive suffixes are nasal sounds (-n, -m, etc.)

- three-way distinction in the local case system, with each set of local cases being divided into forms corresponding roughly to "from", "to", and "in/at"; especially evident, e.g. in Hungarian, Finnish and Estonian, which have several sets of local cases, such as the "inner", "outer" and "on top" systems in Hungarian, while in Finnish the "on top" forms have merged to the "outer" forms.

- the Uralic locative suffix exists in all Uralic languages in various cases, e.g. Hungarian superessive, Finnish essive (-na), North Sami essive, Erzyan inessive, and Nenets locative.

- the Uralic lative suffix exists in various cases in many Uralic languages, e.g. Hungarian illative, Finnish lative (-s as in rannemmas), Erzyan illative, Komi approximative, and Northern Sami locative.

- a lack of grammatical gender, including one pronoun for both he and she; for example, hän in Finnish, tämä in Votic, tema in Estonian, sijə in Komi, ő in Hungarian.

- negative verb, which exists in almost all Uralic languages

- use of postpositions as opposed to prepositions (prepositions are uncommon).

- possessive suffixes

- the genitive is also used to express possession in some languages, e.g. Estonian mu koer, colloquial Finnish mun koira, Northern Sami mu beana 'my dog' (literally 'dog of me'). Separate possessive adjectives and possessive pronouns, such as my and your, are rare.

- dual, in the Samoyedic, Ob-Ugric and Samic languages and reconstructed for Proto-Uralic

- plural markers -j (i) and -t (-d, -q) have a common origin (e.g. in Finnish, Estonian, Võro, Erzya, Samic languages, Samoyedic languages). Hungarian, however, has -i- before the possessive suffixes and -k elsewhere. In the old orthographies, the plural marker -k was also used in the Samic languages.

- Possessions are expressed by a possessor in the adessive or dative case, the verb "be" (the copula, instead of the verb "have") and the possessed with or without a possessive suffix. The grammatical subject of the sentence is thus the possessed. In Finnish, for example, the possessor is in the adessive case: "Minulla on kala", literally "At me is fish", i.e. "I have a fish", whereas in Hungarian, the possessor is in the dative case, but appears overtly only if it is contrastive, while the possessed has a possessive ending indicating the number and person of the possessor: "(Nekem) van egy halam", literally "(To me [dative]) is a fish-my", i.e. "(As for me,) I have a fish".

- expressions that include a numeral are singular if they refer to things which form a single group, e.g. "négy csomó" in Hungarian, "njeallje čuolmma" in Northern Sami, "neli sõlme" in Estonian, and "neljä solmua" in Finnish, each of which means "four knots", but the literal approximation is "four knot". (This approximation is inaccurate for Finnish and Estonian, where the singular is in the partitive case, such that the number points to a part of a larger mass, like "four of knot(s)".)

Phonology

- Vowel harmony: this is present in many but by no means all Uralic languages. It exists in Hungarian and various Baltic-Finnic languages, and is present to some degree elsewhere, such as in Mordvinic, Mari, Eastern Khanty, and Samoyedic. It is lacking in Sami, Permic and standard Estonian, while it does exist in Võro and elsewhere in South Estonian.[47][48] (Although umlaut letters are used in writing Uralic languages, the languages do not exhibit Germanic umlaut; front and back values are intrinsic features of words and modify suffixes, not vice versa as in umlaut.)

- Large vowel inventories. For example, some Selkup varieties have over twenty different monophthongs, and Estonian has over twenty different diphthongs.

- Palatalization of consonants; in this context, palatalization means a secondary articulation, where the middle of the tongue is tense. For example, pairs like [ɲ] – [n], or [c] – [t] are contrasted in Hungarian, as in hattyú [hɒcːuː] "swan". Some Sami languages, for example Skolt Sami, distinguish three degrees: plain ⟨l⟩ [l], palatalized ⟨'l⟩ [lʲ], and palatal ⟨lj⟩ [ʎ], where ⟨'l⟩ has a primary alveolar articulation, while ⟨lj⟩ has a primary palatal articulation. Original Uralic palatalization is phonemic, independent of the following vowel and traceable to the millennia-old Proto-Uralic. It is different from Slavic palatalization, which is of more recent origin. The Finnic languages have lost palatalization, but the eastern varieties have reacquired it, so Finnic palatalization (where extant) was originally dependent on the following vowel and does not correlate to palatalization elsewhere in Uralic.

- Lack of phonologically contrastive tone.

- In many Uralic languages, the stress is always on the first syllable, though Nganasan shows (essentially) penultimate stress, and a number of languages of the central region (Erzya, Mari, Udmurt and Komi-Permyak) synchronically exhibit a lexical accent. The Erzya language can vary its stress in words to give specific nuances to sentential meaning.

Lexicography

Basic vocabulary of about 200 words, including body parts (e.g. eye, heart, head, foot, mouth), family members (e.g. father, mother-in-law), animals (e.g. viper, partridge, fish), nature objects (e.g. tree, stone, nest, water), basic verbs (e.g. live, fall, run, make, see, suck, go, die, swim, know), basic pronouns (e.g. who, what, we, you, I), numerals (e.g. two, five); derivatives increase the number of common words.

Selected cognates

The following is a very brief selection of cognates in basic vocabulary across the Uralic family, which may serve to give an idea of the sound changes involved. This is not a list of translations: cognates have a common origin, but their meaning may be shifted and loanwords may have replaced them.

| English | Proto-Uralic | Finnic | Sami | Mordvin | Mari | Permic | Hungarian | Mansi | Khanty | Samoyed | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finnish | Estonian | Võro | South | North | Kildin | Erzya | Meadow | Komi | Udmurt | Northern | Kazym | Vakh | Tundra Nenets | |||

| 'fire' | *tuli | tuli (tule-) | tuli (tule-) | tuli (tulõ-) |

dålle [tollə] | dolla | tōll | tol | tul | tɨl- | tɨl | – | – | – | – | tuu |

| 'water' | *weti | vesi (vete-) | vesi (vee-) | vesi (vii-) |

– | – | – | ved´ | wüt | va | vu | víz | wit | – | – | jiʔ |

| 'ice' | *jäŋi | jää | jää | ijä | jïenge [jɨeŋə] | jiekŋa | īŋŋ | ej | i | ji | jə | jég | jaaŋk | jeŋk | jeŋk | – |

| 'fish' | *kala | kala | kala | kala | guelie [kʉelie] | guolli | kūll’ | kal | kol | – | – | hal | xuul | xŭɬ | kul | xalʲa |

| 'nest' | *pesä | pesä | pesa | pesä | biesie [piesie] | beassi | piess’ | pize | pəžaš | poz | puz | fészek | pitʲi | – | pĕl | pʲidʲa |

| 'hand, arm' | *käti | käsi (käte-) | käsi (käe-) | käsi (käe-) |

gïete [kɨedə] | giehta | kīdt | ked´ | kit | ki | ki | kéz | kaat | – | köt | – |

| 'eye' | *śilmä | silmä | silm (silma-) | silm (silmä-) |

tjelmie [t͡ʃɛlmie] | čalbmi | čall’m | śeĺme | šinča | śin (śinm-) | śin (śinm-) |

szem | sam | sem | sem | sæwə |

| 'fathom' | *süli | syli (syle-) | süli (süle-) | – | sïlle [sʲɨllə] | salla | sē̮ll | seĺ | šülö | sɨl | sul | öl(el) | tal | ɬăɬ | lö̆l | tʲíbʲa |

| 'vein / sinew' | *sï(x)ni | suoni (suone-) | soon (soone-) | suuń (soonõ-) |

soene [suonə] | suotna | sūnn | san | šün | sən | sən | ín | taan | ɬɔn | lan | teʔ |

| 'bone' | *luwi | luu | luu | luu | – | – | – | lovaža | lu | lɨ | lɨ | – | luw | ɬŭw | lŏγ | le |

| 'blood' | *weri | veri | veri | veri | vïrre [vʲɨrrə] | varra | vē̮rr | veŕ | wür | vur | vir | vér | wiɣr | wŭr | wər | – |

| 'liver' | *mïksa | maksa | maks (maksa-) | mass (massa-) |

mueksie [mʉeksie] | – | – | makso | mokš | mus | mus (musk-) |

máj | maat | mŏxəɬ | muγəl | mudə |

| 'urine' / 'to urinate' |

*kunśi | kusi (kuse-) | kusi (kuse-) | kusi (kusõ-) |

gadtjedh (gadtje-) [kɑdd͡ʒə]- | gožžat (gožža-) | kōnnče | – | kəž | kudź | kɨź | húgy | xuńś- | xŏs- | kŏs- | – |

| 'to go' | *meni- | mennä (men-) | minema | minemä | mïnnedh [mʲɨnnə]- | mannat | mē̮nne | – | mija- | mun- | mɨn- | menni | men- | măn- | mĕn- | mʲin- |

| 'to live' | *elä- | elää (elä-) |

elama (ela-) |

elämä (elä-) |

jieledh [jielə]- |

eallit | jēll’e | – | ila- | ol- | ul- | él- | – | – | – | jilʲe- |

| 'to die' | *ka(x)li- | kuolla (kuol-) | koolma | kuulma (kool-) |

– | – | – | kulo- | kola- | kul- | kul- | hal- | xool- | xăɬ- | kăla- | xa- |

| 'to wash' | *mośki- | – | – | mõskma | – | – | – | muśke- | muška- | mɨśkɨ- | mɨśk- | mos- | – | – | – | masø- |

Orthographical notes: The hacek denotes postalveolar articulation (⟨ž⟩ [ʒ], ⟨š⟩ [ʃ], ⟨č⟩ [t͡ʃ]) (In Northern Sami, (⟨ž⟩ [dʒ]), while the acute denotes a secondary palatal articulation (⟨ś⟩ [sʲ ~ ɕ], ⟨ć⟩ [tsʲ ~ tɕ], ⟨l⟩ [lʲ]) or, in Hungarian, vowel length. The Finnish letter ⟨y⟩ and the letter ⟨ü⟩ in other languages represent the high rounded vowel [y]; the letters ⟨ä⟩ and ⟨ö⟩ are the front vowels [æ] and [ø].

As is apparent from the list, Finnish is the most conservative of the Uralic languages presented here, with nearly half the words on the list below identical to their Proto-Uralic reconstructions and most of the remainder only having minor changes, such as the conflation of *ś into /s/, or widespread changes such as the loss of *x and alteration of *ï. Finnish has even preserved old Indo-European borrowings relatively unchanged as well. (An example is porsas ("pig"), loaned from Proto-Indo-European *porḱos or pre-Proto-Indo-Iranian *porśos, unchanged since loaning save for loss of palatalization, *ś > s.)

Mutual intelligibility

The Estonian philologist Mall Hellam proposed cognate sentences that she asserted to be mutually intelligible among the three most widely spoken Uralic languages: Finnish, Estonian, and Hungarian:[49]

- Estonian: 'Elav kala ujub vee all.

- Finnish: 'Elävä kala ui veden alla.

- Hungarian: 'Eleven hal úszik a víz alatt.

- English: A live fish is swimming underwater.

However, linguist Geoffrey Pullum reports that neither Finns nor Hungarians could understand the other language's version of the sentence.[50]

Comparison

No Uralic language exactly has the idealized typological profile of the family. Typological features with varying presence among the modern Uralic language groups include:[51]

| Feature | Samoyedic | Ob-Ugric | Hungarian | Permic | Mari | Mordvin | Finnic | Samic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Palatalization | + | + | + | + | − | + | − | + |

| Consonant length | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | + |

| Consonant gradation | −1 | − | − | − | − | − | + | + |

| Vowel harmony | −2 | −2 | + | − | + | + | + | − |

| Grammatical vowel alternation (ablaut or umlaut) |

+ | + | − | − | − | − | −3 | + |

| Dual number | + | + | − | − | − | − | − | + |

| Distinction between inner and outer local cases |

− | − | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Determinative inflection (verbal marking of definiteness) |

+ | + | + | − | − | + | − | − |

| Passive voice | − | + | + | − | − | + | + | + |

| Negative verb | + | − | − | + | + | ± | + | + |

| SVO word order | − | − | − | ±4 | − | + | + | + |

Notes:

- Clearly present only in Nganasan.

- Vowel harmony is present in the Uralic languages of Siberia only in some marginal archaic varieties: Nganasan, Southern Mansi and Eastern Khanty.

- A number of umlaut processes are found in Livonian.

- In Komi, but not in Udmurt.

Possible relations with other families

Many relationships between Uralic and other language families have been suggested, but none of these are generally accepted by linguists at the present time.

Indo-Uralic

The Indo-Uralic (or Uralo-Indo-European) hypothesis suggests that Uralic and Indo-European are related at a fairly close level or, in its stronger form, that they are more closely related than either is to any other language family. It is viewed as certain by a few linguists (see main article) and as possible by a larger number.

Uralic–Yukaghir

The Uralic–Yukaghir hypothesis identifies Uralic and Yukaghir as independent members of a single language family. It is currently widely accepted that the similarities between Uralic and Yukaghir languages are due to ancient contacts.[52] Regardless, the hypothesis is accepted by a few linguists and viewed as attractive by a somewhat larger number.

Eskimo–Uralic

The Eskimo–Uralic hypothesis associates Uralic with the Eskimo–Aleut languages. This is an old thesis whose antecedents go back to the 18th century. An important restatement of it is Bergsland 1959.

Uralo-Siberian

Uralo-Siberian is an expanded form of the Eskimo–Uralic hypothesis. It associates Uralic with Yukaghir, Chukotko-Kamchatkan, and Eskimo–Aleut. It was propounded by Michael Fortescue in 1998.

Ural–Altaic

Theories proposing a close relationship with the Altaic languages were formerly popular, based on similarities in vocabulary as well as in grammatical and phonological features, in particular the similarities in the Uralic and Altaic pronouns and the presence of agglutination in both sets of languages, as well as vowel harmony in some. For example, the word for "language" is similar in Estonian (keel) and Mongolian (хэл (hel)). These theories are now generally rejected[53] and most such similarities are attributed to language contact or coincidence.

Nostratic

Nostratic associates Uralic, Indo-European, Altaic, Dravidian, and various other language families of Asia. The Nostratic hypothesis was first propounded by Holger Pedersen in 1903 and subsequently revived by Vladislav Illich-Svitych and Aharon Dolgopolsky in the 1960s.

Eurasiatic

Eurasiatic resembles Nostratic in including Uralic, Indo-European, and Altaic, but differs from it in excluding the South Caucasian languages, Dravidian, and Afroasiatic and including Chukotko-Kamchatkan, Nivkh, Ainu, and Eskimo–Aleut. It was propounded by Joseph Greenberg in 2000–2002. Similar ideas had earlier been expressed by Heinrich Koppelmann (1933) and by Björn Collinder (1965:30–34).

Uralo-Dravidian

The hypothesis that the Dravidian languages display similarities with the Uralic language group, suggesting a prolonged period of contact in the past,[54] is popular amongst Dravidian linguists and has been supported by a number of scholars, including Robert Caldwell,[55] Thomas Burrow,[56] Kamil Zvelebil,[57] and Mikhail Andronov.[58] This hypothesis has, however, been rejected by some specialists in Uralic languages,[59] and has in recent times also been criticised by other Dravidian linguists, such as Bhadriraju Krishnamurti.[60]

All of these hypotheses are minority views at the present time in Uralic studies.

Other comparisons

Various unorthodox comparisons have been advanced such as Finno-Basque and Hungaro-Sumerian. These are considered spurious by specialists.[61]

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Hammarström, Harald; Forkel, Robert; Haspelmath, Martin; Bank, Sebastian, eds. (2016). "Uralic". Glottolog 2.7. Jena: Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

- ↑ Language family tree of Uralic on Ethnologue

- ↑ Tommola, Hannu (2010). "Finnish among the Finno-Ugrian languages". Mood in the Languages of Europe. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 155. ISBN 90-272-0587-6.

- ↑ The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, p. 231.

- ↑ Anderson, J.G.C. (ed.) (1938). Germania. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- ↑ Wickman 1988, pp. 793–794.

- ↑ Collinder 1965.

- ↑ Wickman 1988, pp. 795–796.

- ↑ Wickman 1988, pp. 796-798.

- ↑ Wickman 1988, p. 798.

- ↑ Wickman 1988, pp. 801-803.

- ↑ Wickman 1988, pp. 803–804.

- ↑ Halász, Ignácz (1893). "Az ugor-szamojéd nyelvrokonság kérdése" (PDF). Nyelvtudományi Közlemények (in Hungarian). 23:1: 14–34.

- ↑ Halász, Ignácz (1893). "Az ugor-szamojéd nyelvrokonság kérdése II" (PDF). Nyelvtudományi Közlemények (in Hungarian). 23:3: 260–278.

- ↑ Halász, Ignácz (1893). "Az ugor-szamojéd nyelvrokonság kérdése III" (PDF). Nyelvtudományi Közlemények (in Hungarian). 23:4: 436–447.

- ↑ Halász, Ignácz (1894). "Az ugor-szamojéd nyelvrokonság kérdése IV" (PDF). Nyelvtudományi Közlemények (in Hungarian). 24:4: 443–469.

- ↑ Szabó, László (1969). "Die Erforschung der Verhältnisses Finnougrisch–Samojedisch". Ural-Altaische Jahrbücher. 41: 317–322.

- ↑ Wickman 1988, pp. 799–800.

- ↑ Wickman 1988, pp. 810–811.

- ↑ http://www.sgr.fi/lexica/lexicaxxxv.html

- ↑ Salminen, Tapani, 2009. Uralic (Finno-Ugrian) languages.

- ↑ Helimski, Eugene (2006). "The «Northwestern» group of Finno-Ugric languages and its heritage in the place names and substratum vocabulary of the Russian North". In Nuorluoto, Juhani. The Slavicization of the Russian North (Slavica Helsingiensia 27) (PDF). Helsinki: Department of Slavonic and Baltic Languages and Literatures. pp. 109–127. ISBN 978-952-10-2852-6.

- 1 2 Angela Marcantonio. The Uralic Language Family: Facts, Myths and Statistics (2002, Publications of the Philological Society 35). Pages 55-68.

- 1 2 3 Salminen, Tapani (2002): Problems in the taxonomy of the Uralic languages in the light of modern comparative studies

- ↑ Donner, Otto (1879). Die gegenseitige Verwandtschaft der Finnisch-ugrischen sprachen. Helsinki.

- ↑ Szinnyei, Josef (1910). Finnisch-ugrische Sprachwissenschaft. Leipzig: G. J. Göschen'sche Verlagshandlung. pp. 9–21.

- ↑ Itkonen, T. I. (1921). Suomensukuiset kansat. Helsinki: Tietosanakirjaosakeyhtiö. pp. 7–12.

- ↑ Setälä, E. N. (1926). "Kielisukulaisuus ja rotu". Suomen suku. Helsinki: Otava.

- ↑ Hájdu, Péter (1962). Finnugor népek és nyelvek. Budapest.

- ↑ Hajdu, Peter (1975). Finno-Ugric Languages and Peoples. Translated by G. F. Cushing. London: André Deutch Ltd.. English translation of Hajdú (1962).

- ↑ Collinder, Björn. An Introduction to the Uralic languages. Berkeley / Los Angeles: University of California Press. pp. 8–27.

- ↑ Itkonen, Erkki (1966). Suomalais-ugrilaisen kielen- ja historiantutkimuksen alalta. Tietolipas. 20. Suomalaisen kirjallisuuden seura. pp. 5–8.

- ↑ Austerlitz, Robert (1968). "L'ouralien". In Martinet, André. Le langage.

- ↑ Voegelin, C. F.; Voegelin, F. M. (1977). Classification and Index of the World's Languages. New York/Oxford/Amsterdam: Elsevier. pp. 341–343.

- ↑ Kulonen, Ulla-Maija (2002). "Kielitiede ja suomen väestön juuret". In Grünthal, Riho. Ennen, muinoin. Miten menneisyyttämme tutkitaan. Tietolipas. 180. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. pp. 104–108. ISBN 951-746-332-4.

- ↑ Lehtinen, Tapani (2007). Kielen vuosituhannet. Tietolipas. 215. Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. ISBN 978-951-746-896-1.

- ↑ Janhunen, Juha (2009). "Proto-Uralic – what, where and when?" (pdf). Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran toimituksia. 258. ISBN 978-952-5667-11-0. ISSN 0355-0230.

- ↑ Häkkinen, Kaisa 1984: Wäre es schon an der Zeit, den Stammbaum zu fällen? – Ural-Altaische Jahrbücher, Neue Folge 4.

- 1 2 Häkkinen, Jaakko 2009: Kantauralin ajoitus ja paikannus: perustelut puntarissa. – Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Aikakauskirja 92. http://www.sgr.fi/susa/92/hakkinen.pdf

- ↑ Bartens, Raija (1999). Mordvalaiskielten rakenne ja kehitys (in Finnish). Helsinki: Suomalais-Ugrilainen Seura. p. 13. ISBN 952-5150-22-4.

- ↑ Michalove, Peter A. (2002) The Classification of the Uralic Languages: Lexical Evidence from Finno-Ugric. In: Finnisch-Ugrische Forschungen, vol. 57

- ↑ Janhunen, Juha (2009), "Proto-Uralic – what, where and when?" (pdf), Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran toimituksia, 258, ISBN 978-952-5667-11-0, ISSN 0355-0230

- ↑ Viitso, Tiit-Rein. Keelesugulus ja soome-ugri keelepuu. Akadeemia 9/5 (1997)

- ↑ Viitso, Tiit-Rein. Finnic Affinity. Congressus Nonus Internationalis Fenno-Ugristarum I: Orationes plenariae & Orationes publicae. (2000)

- ↑ Helimski, Eugen. Proto-Uralic gradation: Continuation and traces. In Congressus Octavus Internationalis Fenno-Ugristarum. Pars I: Orationes plenariae et conspectus quinquennales. Jyväskylä, 1995.

- ↑ Häkkinen, Jaakko 2007: Kantauralin murteutuminen vokaalivastaavuuksien valossa. Pro gradu -työ, Helsingin yliopiston Suomalais-ugrilainen laitos.

- ↑ Austerlitz, Robert (1990). "Uralic Languages" (pp. 567–576) in Comrie, Bernard, editor. The World's Major Languages. Oxford University Press, Oxford (p. 573).

- ↑ "Estonian Language" (PDF). Estonian Institute. p. 14. Retrieved 2013-04-16.

- ↑ "The Finno-Ugrics: The dying fish swims in water", The Economist, pp. 73–74, December 24, 2005 – January 6, 2006, retrieved 2013-01-19

- ↑ Pullum, Geoffrey K. (2005-12-26), "The Udmurtian code: saving Finno-Ugric in Russia", Language Log, retrieved 2009-12-21

- ↑ Hájdu, Péter (1975). "Arealógia és urálisztika" (pdf). Nyelvtudományi Közlemények (in Hungarian). 77: 147–152. ISSN 0029-6791.

- ↑ Rédei, Károly 1999: Zu den uralisch-jukagirischen Sprachkontakten. – Finnisch-Ugrische Forschungen 55.

- ↑ cf. e.g. Georg et al. 1999

- ↑ Tyler, Stephen (1968), "Dravidian and Uralian: the lexical evidence". Language 44:4. 798–812

- ↑ Webb, Edward (1860). "Evidences of the Scythian Affinities of the Dravidian Languages, Condensed and Arranged from Rev. R. Caldwell's Comparative Dravidian Grammar". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 7: 271–298. doi:10.2307/592159.

- ↑ Burrow, T. (1944). "Dravidian Studies IV: The Body in Dravidian and Uralian". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies. 11 (2): 328–356. doi:10.1017/s0041977x00072517.

- ↑ Zvelebil, Kamal (2006). Dravidian Languages. In Encyclopædia Britannica (DVD edition).

- ↑ Andronov, Mikhail S. (1971), "Comparative Studies on the Nature of Dravidian-Uralian Parallels: A Peep into the Prehistory of Language Families". Proceedings of the Second International Conference of Tamil Studies Madras. 267–277.

- ↑ Zvelebil, Kamal (1970), Comparative Dravidian Phonology Mouton, The Hauge. at p. 22 contains a bibliography of articles supporting and opposing the hypothesis

- ↑ Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003) The Dravidian Languages Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. ISBN 0-521-77111-0 at p. 43.

- ↑ Trask, R.L. The History of Basque Routledge: 1997 ISBN 0-415-13116-2

Further reading

- Abondolo, Daniel M. (editor). 1998. The Uralic Languages. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-08198-X.

- Austerlitz, Robert. 1990. "Uralic Languages" (pp. 567–576) in Comrie, Bernard, editor. The World's Major Languages. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

- Collinder, Björn. 1955. Fenno-Ugric Vocabulary: An Etymological Dictionary of the Uralic Languages. (Collective work.) Stockholm: Almqvist & Viksell. (Second, revised edition: Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag, 1977.)

- Collinder, Björn. 1957. Survey of the Uralic Languages. Stockholm.

- Collinder, Björn. 1960. Comparative Grammar of the Uralic Languages. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- Collinder, Björn. 1965. An Introduction to the Uralic Languages. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Comrie, Bernhard. 1988. "General Features of the Uralic Languages." In The Uralic Languages, edited by Denis Sinor, pp. 451–477. Leiden: Brill.

- Décsy, Gyula. 1990. The Uralic Protolanguage: A Comprehensive Reconstruction. Bloomington, Indiana.

- Hajdu, Péter. 1963. Finnugor népek és nyelvek. Budapest: Gondolat kiadó.

- Hajdu, Péter. 1975. Finni-Ugrian Languages and Peoples, translated by G. F. Cushing. London: André Deutsch. (English translation of the previous.)

- Helimski, Eugene. Comparative Linguistics, Uralic Studies. Lectures and Articles. Moscow. 2000. (Russian: Хелимский Е.А. Компаративистика, уралистика. Лекции и статьи. М., 2000.)

- Georg, Stefan, Peter A. Michalove, Alexis Manaster Ramer, and Paul J. Sidwell. 1999. "Telling general linguists about Altaic." Journal of Linguistics 35:65–98.

- Koppelmann, Heinrich. 1933. Die eurasische Sprachfamilie. Heidelberg: Carl Winter.

- Laakso, Johanna. 1992. Uralilaiset kansat ('Uralic Peoples'). Porvoo – Helsinki – Juva. ISBN 951-0-16485-2.

- Napolskikh, Vladimir. The First Stages of Origin of People of Uralic Language Family: Material of Mythological Reconstruction. Moscow, 1991. (Russian: Напольских В. В. Древнейшие этапы происхождения народов уральской языковой семьи: данные мифологической реконструкции. М., 1991.)

- Rédei, Károly (editor). 1986–88. Uralisches etymologisches Wörterbuch ('Uralic Etymological Dictionary'). Budapest.

- Ruhlen, Merritt. A Guide to the World's languages, Stanford, California (1987), pp. 64–71.

- Sammallahti, Pekka. 1988. "Historical phonology of the Uralic Languages." In The Uralic Languages, edited by Denis Sinor, pp. 478–554. Leiden: E.J. Brill.

- Sinor, Denis (editor). 1988. The Uralic Languages: Description, History and Foreign Influences. Leiden: Brill.

- Wickman, Bo. 1988. "The History of Uralic Linguistics." In The Uralic Languages, edited by Denis Sinor, pp. 792–818. Leiden: Brill.

External classification

- Bergsland, Knut (1959). "The Eskimo–Uralic hypothesis". Journal de la Société Finno-Ougrienne. 61: 1–29.

- Fortescue, Michael. 1998. Language Relations across Bering Strait. London and New York: Cassell.

- Greenberg, Joseph. 2000–2002. Indo-European and Its Closest Relatives: The Eurasiatic Language Family, 2 volumes. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Pedersen, Holger (1903). "Türkische Lautgesetze". Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft. 57: 535–561.

- Sauvageot, Aurélien. 1930. Recherches sur le vocabulaire des langues ouralo-altaïques ('Research on the Vocabulary of the Uralo-Altaic Languages'). Paris.

Linguistic issues

- Künnap, A. 2000. Contact-induced Perspectives in Uralic Linguistics. LINCOM Studies in Asian Linguistics 39. München: LINCOM Europa. ISBN 3-89586-964-3.

- Wickman, Bo. 1955. The Form of the Object in the Uralic Languages. Uppsala: Lundequistska bokhandeln.

External links

- Finnic and Finno-Ugric Swadesh vocabulary lists on Wiktionary

- "The Finno-Ugrics" The Economist, December 20, 2005

- News on the Uralic peoples

- Kulonen, Ulla-Maija: Origin of Finnish and related languages. thisisFINLAND, Finland Promotion Board. Cited 30.10.2009.

"Rebel" Uralists

- "The untenability of the Finno-Ugrian theory from a linguistic point of view" by Dr. László Marácz, a minority opinion on the language family

- "The 'Ugric-Turkic battle': a critical review" by Angela Marcantonio, Pirjo Nummenaho, and Michela Salvagni

- "Linguistic shadow-boxing" by Johanna Laakso – a book review of Angela Marcantonio’s The Uralic Language Family: Facts, Myths and Statistics

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Uralic languages. |

.png)