Uterine microbiome

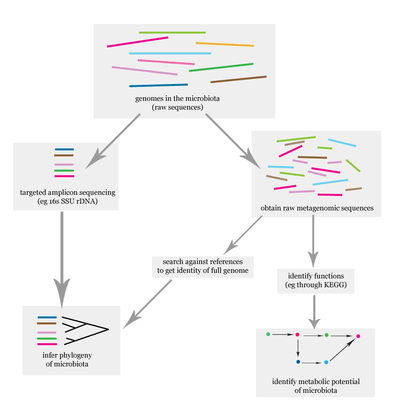

The uterine microbiome is the commensal, nonpathogenic, bacteria present in a healthy uterus and endometrium and the specific environment which they inhabit. It has been only recently confirmed that the uterus and its tissues are not sterile.[1] Due to improved 16S rRNA gene sequencing techniques, detection of bacteria that are present in low numbers is possible.[2] Using this procedure that allows the detection of bacteria that cannot be cultured outside the body, studies of microbiota present in the uterus are expected to increase.[3]

Characteristics

Bacteria, viruses and one genus of yeasts are a normal part of the uterus before and during pregnancy.[1][4] The uterus has been found to possess its own characteristic microbiome that differs significantly from the vaginal microbiome. Despite its close spatial connection with the vagina, the microbiome of the uterus more closely resembles the commensal bacteria found in the oral cavity.[1] In addition, the immune system is able to differentiate between those bacteria normally found in the uterus and those that are pathogenic. Hormonal changes have an effect on the microbiota of the uterus.[5]

Taxa

The organisms listed below have been identified as commensals. Some also have the potential for growing to the point of causing disease:

| Organism | Commensal | Transient | Potential pathogen |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

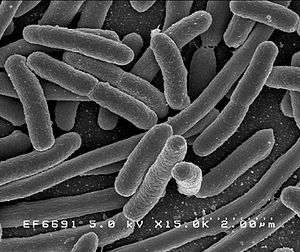

| Escherichia coli | x | x | [1][5][6] | |

| Escherichia spp. | x | x | [1][5][6] | |

| Ureaplasma parvum | x | x | [1][5] | |

| Fusobacterium nucleatum | x | [7] | ||

| Prevotella tannerae | x | [4] | ||

| Bacteroides spp. | x | [4] | ||

| Streptomyces avermitilis | x | [1][5] | ||

| Mycoplasma spp. | x | x | [4] | |

| Neisseria lactamica | x | [1][5] | ||

| Neisseria polysaccharea | x | [1][5] | ||

| Epstein-Barr virus | x | x | [4] | |

| Respiratory-Syncytial virus | x | x | [4] | |

| Adenovirus | x | x | [4] | |

| Candida spp. | x | x | [4] |

Other taxa, while not causing signs or symptoms of disease, are associated with a negative birth outcome.[1][4][5]

Clinical significance

Treatment for infertility has often involved the injection of prophylactic antibiotics into the uterus when transferring embryos, with the intention of increasing successful implantation rates. A 2012 review found no association between successful implantation and antibiotic treatment. This research found that antibiotic treatment was associated with a decrease in culturable bacteria, but did not screen for non-culturable bacteria remaining after treatment. These microbiota or their fragments may be involved in regulating the immune system.[8] Infertility treatments often progress to the point where a microbiological analysis of the uterine microbiota is performed.[1]

Immune response

The healthy uterine microbiota at the mucosal-epithelium and trophoblast implantation site is regulated by macrophages. These macrophages control the microbiota and secrete antimicrobial substances that regulate the population of the commensal bacteria and help to prevent infection with pathogenic bacteria.[1]

References and notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Mor, Gil; Kwon, Ja-Young (2015). "Trophoblast-microbiome interaction: a new paradigm on immune regulation". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 213 (4): S131–S137. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2015.06.039. ISSN 0002-9378. PMID 26428492.

- ↑ Verstraelen, Hans; Vilchez-Vargas, Ramiro; Desimpel, Fabian; Jauregui, Ruy; Vankeirsbilck, Nele; Weyers, Steven; Verhelst, Rita; De Sutter, Petra; Pieper, Dietmar H.; Van De Wiele, Tom (2016). "Characterisation of the human uterine microbiome in non-pregnant women through deep sequencing of the V1-2 region of the 16S rRNA gene". PeerJ. 4: e1602. doi:10.7717/peerj.1602. ISSN 2167-8359.

- ↑ Wassenaar, T.M.; Panigrahi, P. (2014). "Is a foetus developing in a sterile environment?". Letters in Applied Microbiology. 59 (6): 572–579. doi:10.1111/lam.12334. ISSN 0266-8254. PMID 25273890.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Payne, Matthew S.; Bayatibojakhi, Sara (2014). "Exploring Preterm Birth as a Polymicrobial Disease: An Overview of the Uterine Microbiome". Frontiers in Immunology. 5: 595. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00595. ISSN 1664-3224. PMC 4245917

. PMID 25505898.

. PMID 25505898. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Yarbrough, V. L.; Winkle, S.; Herbst-Kralovetz, M. M. (2014). "Antimicrobial peptides in the female reproductive tract: a critical component of the mucosal immune barrier with physiological and clinical implications". Human Reproduction Update. 21 (3): 353–377. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmu065. ISSN 1355-4786. PMID 25547201.

- 1 2 Todar, K. "Pathogenic E. coli". Online Textbook of Bacteriology. University of Wisconsin–Madison Department of Bacteriology. Retrieved 2007-11-30.

- ↑ Prince, Amanda L.; Antony, Kathleen M.; Chu, Derrick M.; Aagaard, Kjersti M. (2014). "The microbiome, parturition, and timing of birth: more questions than answers". Journal of ReproductiveImmunology. 104-105: 12–19. doi:10.1016/j.jri.2014.03.006. ISSN 0165-0378.

- ↑ Franasiak, Jason M.; Scott, Richard T. (2015). "Reproductive tract microbiome in assisted reproductive technologies". Fertility and Sterility. 104 (6): 1364–1371. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.10.012. ISSN 0015-0282. PMID 26597628.

See also

- Human microbiome project

- Human virome

- List of bacterial vaginosis microbiota

- Vaginal microbiota in pregnancy

- Placental microbiome

- List of antimicrobial peptides in the female reproductive tract