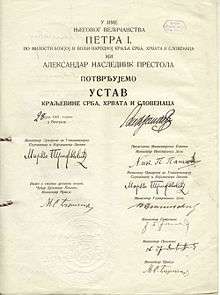

Vidovdan Constitution

The Vidovdan Constitution was the first constitution of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. It was approved by the Constitutional Assembly on June 28, 1921 despite the opposition boycotting the vote. The Constitution is named after the feast of St. Vitus (Vidovdan), a Serbian Orthodox holiday. The Constitution required a simple majority to pass. Out of 419 representatives, 223 voted for, 35 voted against and 161 abstained.[1]

The Constitution was in effect until King Alexander proclaimed his January 6th Dictatorship on that date in 1929.

Vote

For

Against

- Yugoslav Social-Democratic Party

- Yugoslav Republican Party

- Foreign Minister Ante Trumbić

Boycotted

- Communist Party of Yugoslavia - left assembly in June

- Croatian Republican Peasant Party - boycotted assembly since 1920 elections

- Slovenian People's Party - left assembly in June

- Croatian People's Party - left assembly in June

- Croatian Union - left assembly in May

Alternative proposals

Croatian Republican Peasant Party

The Croatian Republican Peasant Party adopted its Constitution of the neutral peasant republic of Croatia in Zagreb on April 1, 1921.[2]

Croatian Union

The Croatian Union had proposed a confederation of the kingdom into six entities:[3]

- Serbia

- Croatia

- Montenegro

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

- Vojvodina

- Slovenia

Aftermath

On June 30, an editorial in the People's Radical Party's journal Samouprava stated: ″This year's Vidovdan restored an empire to us″.[4] On July 21 Minister of the Interior, and member of the People's Radical Party, Milorad Drašković was assassinated in Delnice by a group of communist activists.[5]

The viability of the constitution dominated the 1923 parliamentary elections.[6]

The Croatian Peasant Party did not accept the legitimacy of the constitution. After the 1925 elections, entry into the government was offered to the party by Nikola Pašić. The Croatian Peasant Party accepted the offer, agreeing to recognize the constitution. This led to the release of the party's leader Stjepan Radić from prison, along with other party officials.[7]

References

- ↑ Robert J. Donia, John Van Antwerp Fine; Bosnia and Hercegovina: A Tradition Betrayed. Columbia University Press, 1995. (p. 126)

- ↑ Pod teretom nerešenog nacionalnog pitanja, Danas

- ↑ Anne Lane, Yugoslavia: When Ideals Collide.(New York Palgrave Macmillan; 2004). (p. 54)

- ↑ Banac 1988, p. 404.

- ↑ Ramet 1988, p. 58.

- ↑ Joseph Rothschild, Peter F. Sugar, Donald Warren Treadgold; East Central Europe Between the Two World Wars. University of Washington Press, 1979. (p.218)

- ↑ R. J. Crampton, Eastern Europe in the twentieth century. Routledge, 1994. (p. 137)

- Banac, Ivo (1988). The National Question in Yugoslavia: Origins History, Politics. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-80149-493-1.

- Ramet, Sabrina (2006). The Three Yugoslavias: State-Building And Legitimation, 1918-2005. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-25334-656-8.