Gus Grissom

| Gus Grissom | |

|---|---|

_Grissom_portrait.jpg) | |

| NASA Astronaut | |

| Nationality | United States |

| Status | Killed during training |

| Born |

Virgil Ivan Grissom April 3, 1926 Mitchell, Indiana, U.S. |

| Died |

January 27, 1967 (aged 40) Cape Kennedy, Florida, U.S. |

Other occupation | Test pilot |

|

Purdue University, B.S. 1950 Air Force Institute of Technology, B.S. 1956 | |

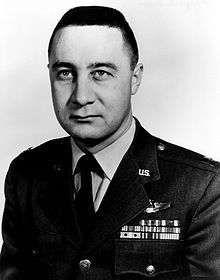

| Rank | Lieutenant Colonel, USAF |

Time in space | 5h 7m |

| Selection | 1959 NASA Group 1 |

| Missions | Mercury-Redstone 4, Gemini 3, Apollo 1 |

Mission insignia |

|

| Awards |

Distinguished Flying Cross Congressional Space Medal of Honor NASA Distinguished Service Medal |

Lieutenant Colonel Virgil Ivan "Gus" Grissom (April 3, 1926 – January 27, 1967) was one of the original NASA Project Mercury astronauts, a United States Air Force test pilot and a mechanical engineer. He was the second American to fly in space, and the first member of the NASA Astronaut Corps to fly in space twice.

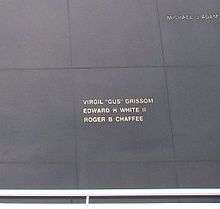

Grissom was killed along with fellow astronauts Ed White and Roger Chaffee during a pre-launch test for the Apollo 1 mission at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station (then known as Cape Kennedy), Florida. He was the first of the Mercury Seven to die. He was also a recipient of the Distinguished Flying Cross and, posthumously, the Congressional Space Medal of Honor.

Biography

Family and background

Grissom was born in Mitchell, Indiana, on April 3, 1926, the second child of Dennis David Grissom and Cecile King Grissom.[1] His father was a signalman for the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, and his mother a homemaker. His older sister died shortly before his birth, and he was followed by three younger siblings, Wilma, Norman and Lowell.[2] As a child he attended the local Church of Christ where he remained a lifelong member and joined the Boy Scouts' Troop 46. He earned the rank of Star Scout.[3]

Grissom, who reportedly had an IQ of 145, attended public elementary schools, and went on to Mitchell High School. He met and befriended Betty Lavonne Moore at school through their extracurricular activities. His boy scout troop carried the American flag at school basketball games, while she played the drum in the high school band. His first jobs were delivering newspapers for the Indianapolis Star in the morning, and the Bedford Times in the evening. He also worked at a local meat market, a service station, and a clothing store.[4] He occasionally spent time at a local airport in Bedford, Indiana, where he first became interested in flying. A local attorney who owned a small plane would take him on flights for a $1 fee and taught him the basics of flying an airplane.[5]

World War II

World War II broke out while Grissom was still in high school, and he was eager to enlist upon graduation. He enlisted as an aviation cadet in the United States Army Air Forces, and completed an entrance exam in November 1943. He graduated from high school in 1944, and was inducted into the United States Army at Fort Benjamin Harrison, Indiana, on August 8, 1944. He was sent to Sheppard Field in Wichita Falls, Texas, for basic flight training after which he was sent to Brooks Field in San Antonio, Texas, and then, in January 1945, was assigned to Boca Raton Army Airfield in Florida as a clerk.[6]

As the war neared its end, Grissom sought to be discharged. He married Betty Moore on July 6, 1945, at the First Baptist Church in Mitchell while on leave. His brother Norman served as his best man. He was discharged from the Army in November 1945, two months after the war ended. He took a job at Carpenter Body Works, a local bus manufacturing business, and rented an apartment in Mitchell. However, he had trouble providing a sufficient income and was determined to attend college. Using the G.I. Bill for partial payment of his school tuition, Grissom enrolled at Purdue University in September 1946. During his time in college, Betty returned to live with her parents and took a job at the Indiana Bell Telephone Company while he worked part-time as a cook at a local restaurant. Grissom took summer classes to finish early and graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree in Mechanical Engineering in February 1950.[7]

Korean War

Grissom re-enlisted in the military after his graduation from Purdue, this time in the newly formed United States Air Force. He was accepted into the air cadet basic training program at Randolph Air Force Base in Universal City, Texas. Upon completion of the program, he was assigned to Williams Air Force Base in Mesa, Arizona.[8] In March 1951 Grissom received his pilot wings and commission as a Second Lieutenant.[9] Betty remained in Indiana, and while he was away his first child, Scott, was born. After his birth they joined Grissom in Arizona.[10] The family remained there only briefly and in December 1951 they moved to Presque Isle, Maine, where Grissom was assigned to Presque Isle Air Force Base and became a member of the 75th Fighter Interceptor Squadron.[11]

With the ongoing Korean War, Grissom's squadron was dispatched to the war zone in February 1952. There he flew as an F-86 Sabre replacement pilot and was reassigned to the 334th Fighter Squadron of the 4th Fighter Interceptor Wing stationed at Kimpo Air Base.[12] Grissom flew 100 combat missions, serving as a wingman protecting the lead fighters. The position was not one that put him in a position to attack the enemy and he did not shoot down any planes while he was in service. He did personally drive off Korean air raids on multiple occasions as their MiGs would often flee at the first sign of superior American aircraft.[13] On March 11, 1952, Grissom was promoted to First Lieutenant and was cited for his "superlative airmanship".[14] He was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross and the Air Medal with an oak leaf clusters.[15]

Grissom requested to remain in Korea to fly another 25 flights, but his request was denied. He was given the option of which base he would like to be stationed at in the United States and he requested Bryan AFB in Bryan, Texas. There he served as a flight instructor, and was joined by his wife and son. His second child was born there in 1953.[16] During a training exercise with a cadet, a trainee pilot caused a flap to break off the plane, causing it to spin out of control. Grissom climbed from the rear seat of the small craft to take over the controls and safely land the jet.[17]

In August 1955, Grissom was reassigned to the U.S. Air Force Institute of Technology located in Dayton, Ohio. There he earned a Bachelor of Science degree in Aeromechanics in 1956, after completing the year-long course.[18] In October 1956, he entered USAF Test Pilot School at Edwards Air Force Base, California, and returned to Wright-Patterson AFB in May 1957 as a test pilot assigned to the fighter branch.[19][20]

NASA career

In 1958, Grissom received an official teletype message instructing him to report to an address in Washington, D.C. wearing civilian clothes. The message was classified "Top Secret" and Grissom was not to discuss its contents with anyone. He was one of 110 military test pilots whose credentials had earned them an invitation to learn more about the space program in general and Project Mercury in particular. Grissom liked the sound of the program, but knew that competition for the final spots would be fierce.[21]

Grissom was sent to the Lovelace Clinic and Wright-Patterson Air Force Base to receive extensive physical examinations and to submit to a battery of psychological tests. He was nearly disqualified when doctors discovered that he suffered from hay fever, but was permitted to continue on when it was determined that his allergies would not be a problem due to the absence of ragweed pollen in space. On April 13, 1959, Grissom received official notification that he had been selected as one of the seven Project Mercury astronauts.[22][23]

Project Mercury

On July 21, 1961, Grissom was pilot of the second Project Mercury flight, Mercury-Redstone 4, which he named Liberty Bell 7.[21] This was a sub-orbital flight that lasted 15 minutes and 37 seconds.[20] After splashdown, emergency explosive bolts unexpectedly fired and blew the hatch off, causing water to flood into the spacecraft. Quickly exiting through the open hatch and into the ocean, Grissom was nearly drowned as water began filling his spacesuit.[21] A recovery helicopter tried to lift and recover the spacecraft, but the flooding spacecraft became too heavy, and it was ultimately cut loose before sinking.[21]

Grissom asserted he had done nothing to cause the hatch to blow. Robert F. Thompson, Director of Mercury Operations, was dispatched to the USS Randolph by Space Task Group Director Robert Gilruth and spoke with Grissom upon Grissom's arrival on the aircraft carrier. Grissom explained that he had gotten ahead in the mission timeline and had pulled the pip-pin that released the metal trigger for the explosive egress hatch. Once the pin was removed, the trigger was no longer held in place and could have inadvertently fired as a result of ocean wave action, bobbing as a result of helicopter rotor wash, or other activity. NASA officials concluded Grissom had not necessarily initiated the firing of the explosive hatch. The full story was revealed for the first time at the Space Center Lecture Series lecture by Thompson and Grissom recovery helicopter pilot Dr. James Lewis on the fiftieth anniversary of the event.[24] As a result of the difficulties, astronaut training for upcoming flights stressed not removing the pip pin until immediately prior to hatch detonation and modifications were made to the Mercury pressure suit to automatically close inlet valves in order to preclude the entry of ocean water. Gilruth and Thompson decided no further changes or actions were required.

Initiating the explosive egress system called for pushing or hitting the metal trigger with the hand, which unavoidably left a large, obvious bruise on the astronaut's hand,[25] but Grissom was found not to have any of the tell-tale bruising. Still, controversy remained, and fellow Mercury astronaut Wally Schirra, at the end of his October 3, 1962, flight, remained inside his spacecraft until it was safely aboard the recovery ship, and made a point of deliberately blowing the hatch to get out, bruising his hand.[26]

Grissom's spacecraft was recovered in 1999, but no further evidence was found which could conclusively explain how the explosive hatch release had occurred. Later, Guenter Wendt, pad leader for the early American manned space launches, wrote that he believed a small cover over the external release actuator was accidentally lost sometime during the flight or splashdown and the T-handle may have been tugged by a stray parachute suspension line, or was perhaps damaged by the heat of re-entry and after cooling upon splashdown, contracted and fired.[22][27]

Grissom was surrounded by reporters in a news conference after his space flight in America's second manned ship. When asked how he felt, he replied, "Well, I was scared a good portion of the time; I guess that's a pretty good indication."[28]

Project Gemini

In early 1964 Alan Shepard was grounded after being diagnosed with Ménière's disease and Grissom was designated command pilot for Gemini 3, the first manned Project Gemini flight, which flew on March 23, 1965.[21] This mission made him the first NASA astronaut to fly into space twice.[29] This flight made three revolutions of the Earth and lasted for 4 hours, 52 minutes and 31 seconds.

Grissom was one of the eight pilots of the NASA paraglider research vehicle.[30]

Grissom was one of the smaller astronauts, and he worked very closely with the engineers and technicians from McDonnell Aircraft who built the Gemini spacecraft. The first three spacecraft were built around him and the design was humorously referred to as "the Gusmobile". However, by July 1963 NASA discovered 14 out of the 16 astronauts could not fit themselves into the cabin and later cockpits were modified.[31] During this time Grissom invented the multi-axis translation thruster controller used to push the Gemini and Apollo spacecraft in linear directions for rendezvous and docking.[32]

Naming of the Molly Brown

In a joking nod to the sinking of his Mercury craft, Grissom named the first Gemini spacecraft Molly Brown (after the popular Broadway show The Unsinkable Molly Brown);[21] NASA publicity officials were unhappy with this name. When Grissom and his Pilot John Young were ordered to come up with a new one, they offered Titanic.[21] NASA executives gave in and allowed the name Molly Brown, but did not use it in any official references. Subsequently and much to the agency's chagrin, on launch CAPCOM Gordon Cooper gave Gemini 3 its sendoff by telling Grissom and Young, "You're on your way, Molly Brown!" and ground controllers used this name throughout the flight.[33]

After the safe return of Gemini 3, NASA announced new spacecraft would not be named. Hence Gemini 4 was not named American Eagle as its crew had planned. The naming of spacecraft resumed in 1967 after managers found the Apollo flights needed a name for each of two flight elements, the Command Module and Lunar Module. Lobbying by the astronauts and senior NASA administrators also had an effect. Apollo 9 had the callsigns Gumdrop for the Command Module and Spider for the Lunar Module. However, Wally Schirra had been prevented from naming his Apollo 7 spacecraft Phoenix in honor of Grissom's Apollo 1 crew since it was believed the average taxpayer would not take a "fire" metaphor as intended.

Apollo program

Grissom was backup Command Pilot for Gemini 6A when he shifted to the Apollo program and was assigned as Commander of the first manned mission AS-204, with Senior Pilot Ed White, who had flown in space on Gemini 4 mission when he became the first American to make a spacewalk, and Pilot Roger B. Chaffee.[21] The three men were granted permission to refer to their flight as Apollo 1 on their mission insignia patch.

Death

I said, how are we gonna get to the Moon if we can't talk between two or three buildings?

Grissom expressing frustration with the Apollo comm system[34]

Before its planned February 21, 1967, launch, the Command Module interior caught fire and burned on January 27, 1967, during a pre-launch test on Launch Pad 34 at Cape Kennedy, killing all three men. The fire's ignition source was never determined, but their deaths were attributed to a wide range of lethal hazards in the early Apollo Command Module design and conditions of the test, including a pressurized 100% oxygen pre-launch atmosphere, many wiring and plumbing flaws, flammable materials used in the cockpit and in the astronauts' flight suits, and an inward-opening hatch which could not be opened quickly in an emergency and could not be opened at all with full internal pressure.[35]

The engineers who programmed the Apollo simulator used for training had a difficult time keeping the simulator in synch with the changes continuously being made to the spacecraft. According to backup astronaut Walter Cunningham, "We knew that the spacecraft was, you know, in poor shape relative to what it ought to be. We felt like we could fly it, but let's face it, it just wasn't as good as it should have been for the job of flying the first manned Apollo mission." NASA pressed on, and mid January 1967, preparations were being made for the final preflight tests of Spacecraft 012.[36]

The simulator problems proved extremely annoying to Grissom. On January 22, 1967, before returning to the Cape to conduct the January 27 plugs-out test, Grissom took a lemon off a tree in his back yard. When his wife Betty asked him what he planned to do with it, he replied, "I'm going to hang it on that spacecraft."[36] He actually hung the lemon on the simulator, not the spacecraft.

After the tragedy, NASA adopted a new flight numbering system for Apollo, and honored the crew by making Apollo 1 official. The spacecraft problems were corrected, and the Apollo program carried on successfully to reach its objective of landing men on the Moon.

Grissom had attained the rank of Lieutenant Colonel at the time of his death, and had logged a total of 4,600 hours flying time, including 3,500 hours in jet airplanes. Chief astronaut Deke Slayton wrote that he wanted one of the original Mercury Seven astronauts to be the first on the Moon and, "Had Gus been alive, as a Mercury astronaut he would have taken the step ... My first choice would have been Gus, which both Chris Kraft and Bob Gilruth seconded."[37]

Gus Grissom is buried in Section 3, plot number 2503-E, 38°52′23″N 77°04′22″W / 38.873115°N 77.072755°W of the Arlington National Cemetery, directly beside Roger Chaffee, plot number 2502-F. Ed White is buried at the West Point Cemetery, West Point, New York.

Spacesuit controversy

When the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame opened in 1990, his family lent the spacesuit worn by Grissom during Mercury 4 along with other personal artifacts belonging to the astronaut. In 2002, the museum went into bankruptcy and was taken over by a NASA contractor, whereupon the family asked for everything back.[38] All the artifacts were returned to them except the spacesuit, which NASA claimed was government property.[39] NASA insisted Grissom got authorization to use the spacesuit for a show and tell at his son's school and never returned it, but some Grissom family members claimed the astronaut rescued the spacesuit from a scrap heap.[40]

Personal life

Grissom and his wife Betty (born 1927) had two sons: Scott (born May 16, 1950) and Mark (born December 30, 1953).[41] He greatly valued being home with his family, stating that "it sure helped to spend a quiet evening with your wife and children in your own living room." His wife Betty accommodated his hectic schedule by completing major chores and errands during the week so weekends would be free for family activities. Grissom refused to let work problems intrude on his time at home and tried to complete technical reading or paperwork after the boys were asleep. Gus also introduced his sons to hunting and fishing, two of his favorite hobbies.[42]

Awards and honors

| ||

- Air Force Command Pilot rating with astronaut qualifier

- Honorary Doctorate, Florida Institute of Technology

- John J. Montgomery Award

- Member of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots[20]

- Honorary Mayor of Newport News, Virginia (posthumous)

- Inducted into the International Space Hall of Fame in 1981.[43]

- Enshrined in the National Aviation Hall of Fame in 1987.[44]

- Inducted into the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame on May 11, 1990.[45]

- Enshrined at the "Wall of Honor" at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum's Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center at Washington Dulles International Airport

- In a 2010 Space Foundation survey, Grissom was ranked as the #9 (tied with astronauts Buzz Aldrin and Alan Shepard) most popular space hero.[46]

Memorials

- There are three streets in Buffalo, New York, named after the Apollo 1 astronauts: Gus Grissom Drive, Roger Chaffee Drive and Edward White Drive.

If we die, we want people to accept it. We are in a risky business and we hope that if anything happens to us it will not delay the program. The conquest of space is worth the risk of life.

— Grissom, after his Gemini mission, March 1965[47]

- The dismantled Launch Pad 34 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station bears two memorial plaques: One reads, They gave their lives in service to their country in the ongoing exploration of humankind's final frontier. Remember them not for how they died but for those ideals for which they lived. and the other, In memory of those who made the ultimate sacrifice so others could reach for the stars. Ad astra per aspera, (a rough road leads to the stars). God speed to the crew of Apollo 1.[48]

- Grissom is named with his Apollo 1 crewmates on the Space Mirror Memorial at Kennedy Space Center Visitor Complex in Florida.

- Grissom crater is one of several located on the far side of the Moon named for Apollo astronauts, near a large crater (walled plain) named Apollo.

- Grissom Hill is one of the Apollo 1 Hills on Mars, located 4.7 miles (7.6 km) southwest of Columbia Memorial Station.

- Navi (Ivan spelled backwards), a nickname for the star Gamma Cassiopeiae: Grissom used this name, plus two others for White and Chaffee, on his Apollo 1 mission planning star charts as a joke, and the succeeding Apollo astronauts kept using the names as a memorial.[49][50]

- 2161 Grissom is a main belt asteroid.

- The airport in Bedford, Indiana where Grissom flew as a teenager was renamed Virgil I. Grissom Municipal Airport.

- Grissom's boyhood home on Grissom Avenue (renamed in his honor after his Mercury flight[51]) in Mitchell, Indiana, is currently being restored into a museum.

- A limestone carving of the Titan II rocket which launched his Gemini flight is in downtown Mitchell, Indiana. There is also a memorial in nearby Spring Mill State Park.

- The auditorium in Mitchell High School, which Grissom attended.

- Virgil I. Grissom Library, Denbigh section of Newport News, Virginia.

- Virgil I. Grissom Bridge across the Hampton River, on Rt 258 (Mercury Blvd, named after the Mercury program) in Hampton, VA, is one of the six bridges and one road named after the original 7 Mercury astronauts, who trained in the area.

- Virgil "Gus" Grissom Park, Fullerton, California. (Fullerton also has parks named for White and Chaffee).[52]

- The Gus Grissom Stakes, a thoroughbred horse race run in Indiana each fall; originally held at Hoosier Park in Anderson, moved in 2014 to Indiana Grand Race Course in Shelbyville.

- Grissom Island, artificial island, Long Beach Harbor off Southern California (along with White & Chaffee Islands).[53][54]

- The Virgil I. Grissom Museum is located just inside the entrance to Spring Mill State Park in Mitchell, Indiana.[55]

Military

- Bunker Hill Air Force Base in Peru, Indiana, was renamed on May 12, 1968, to Grissom Air Force Base. In 1994, it was again renamed to Grissom Air Reserve Base following the USAF's realignment program.[56] The three-letter identifier of the VHF Omni Directional Radio Range (VOR) located at Grissom Air Reserve Base is GUS, Grissom's nickname

- Grissom Dining Facility, Misawa Air Base, Japan.

- Grissom was the "Class Exemplar" of the United States Air Force Academy class of 2007.

- Grissom Hall at the former Chanute Air Force Base, Rantoul, Illinois, where Minuteman missile maintenance training was conducted.

- Grissom Avenue at the former Mather Air Force Base, now known as Sacramento Mather Airport, Rancho Cordova, California, is one of a number of streets at the former base named after Mercury, Gemini and Apollo program astronauts.

Schools

- Grissom Hall at Purdue University, his alma mater, was the home of the School of Aeronautics and Astronautics for several decades. It is currently home of the Purdue department of Industrial Engineering.[57]

- Grissom Hall, Florida Institute of Technology.

- Grissom Hall, State University of New York at Fredonia.

- Virgil I. Grissom High School, Huntsville, Alabama.[58] (Huntsville also has schools named for Roger Chaffee, Ed White, Mae Jemison, Ronald McNair and the lost space shuttles: Roger B. Chaffee Elementary School, Ed White Middle School, Challenger Middle School, and Columbia High School)[59]

- Virgil I. Grissom Middle School, Mishawaka, Indiana.

- Virgil I. Grissom Middle School, Tinley Park, Illinois.

- Virgil I. Grissom Middle School, Sterling Heights, Michigan.

- Virgil I. Grissom Junior High School 226, South Ozone Park, Queens, New York City, New York.

- Grissom Elementary School, Gary, Indiana.

- Grissom Elementary School, Muncie, Indiana.

- Virgil I. Grissom Elementary School in the Hegewisch community of Chicago, Illinois.

- Virgil Grissom Elementary School, Princeton, Iowa.

- Virgil Grissom Elementary School, Old Bridge, New Jersey. (This school was named for Grissom several years before his death.)[60]

- Virgil I. Grissom School No. 7, Rochester, New York.

- Grissom Elementary School, Tulsa, Oklahoma[61]

- Virgil I. Grissom Elementary School, Houston, Texas.[62]

- V.I. Grissom Elementary School, at the closed Clark Air Base, Philippines.

Film and television

Grissom has been noted and remembered in many film and television productions. Before he became widely known as an astronaut, the film Air Cadet (1951) starring Richard Long and Rock Hudson briefly featured Grissom early in the movie as a U.S. Air Force candidate for flight school at Randolph Field, San Antonio, Texas. Grissom was depicted by Fred Ward in the film The Right Stuff (1983) and (very briefly) in the film Apollo 13 (1995) by Steve Bernie. He was portrayed in the 1998 HBO miniseries From the Earth to the Moon (1998) by Mark Rolston. Actor Kevin McCorkle played Grissom in the third season finale of the NBC television show American Dreams. Bryan Cranston played Grissom as a nervous variety-show guest in the film That Thing You Do! Actor Joel Johnstone portrays Gus Grissom in the 2015 ABC TV series The Astronaut Wives Club

In the 1984 film Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, the Federation starship USS Grissom is named for Grissom.[63] Another USS Grissom was featured in a 1990 episode of the TV series Star Trek: The Next Generation,[64] and was mentioned in a 1999 episode of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine.[65]

The character Gus Griswald in the popular children's TV show Recess is named after Grissom (his fictional father is a General in the US Army and Gus is his recruit). The character Gil Grissom in the CBS television series CSI: Crime Scene Investigation[66] and the character Virgil Tracy in the British television series Thunderbirds[67] are also named after the astronaut.

NASA footage including Grissom's Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo missions was released in high definition on the Discovery Channel in June 2008 in the television series When We Left Earth: The NASA Missions.[22]

Books

At the time of his death, Grissom had been putting the finishing touches on Gemini!: A Personal Account of Man's Venture Into Space; he had been heavily involved in the engineering of the spacecraft. The final chapter is dated January 1967, a few days before Grissom's death on the Apollo launch pad. According to editor Jacob Hay, the book's final form was "reached with the approval of Mrs. Betty Grissom."

A book titled Seven Minus One: The Story of Astronaut Gus Grissom was published in 1968 by Carl L. Chappell, Ph.D. through New Frontier Publishing Co. of Madison, Indiana, and is probably the earliest biography of Col. Grissom.

Betty Grissom co-wrote a memoir with Henry Still, titled Starfall (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1974.)

A family-approved account of Grissom's life appears in the 2003 book Fallen Astronauts by Colin Burgess and Kate Doolan.

The Indiana Historical Society commissioned Gus Grissom: The Lost Astronaut by Ray E. Boomhower, as part of its "Indiana Biography Series".[68] It was first published in 2004.

"Calculated Risk: The Supersonic Life and Times of Gus Grissom," by George Leopold published by Purdue University Press 2016.

Notes

- ↑ Boomhower, p. 39

- ↑ Boomhower, p. 40

- ↑ "Scouting and Space Exploration". Boy Scouts of America. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 25, 2014.

- ↑ Boomhower, pp. 42–45

- ↑ Boomhower, p. 47

- ↑ Boomhower, pp. 48–49

- ↑ Boomhower, pp. 50–56

- ↑ Boomhower, p. 57

- ↑ Boomhower, p. 58

- ↑ Boomhower, p. 59

- ↑ Boomhower, p. 60

- ↑ Boomhower, p. 63

- ↑ Grissom, p. 66

- ↑ Grissom, p. 67

- ↑ Burgess, p. 59

- ↑ Boomhower, p. 68

- ↑ Boomhower, p. 69

- ↑ Boomhower, p. 71

- ↑ "Astronaut Biographies: Virgil I. (Gus) Grissom". U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on October 8, 2007. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- 1 2 3 "Astronaut Bio: Virgil I. Grissom". Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "NASA History". NASA.

- 1 2 3 Discovery Channel, When We Left Earth: The NASA Missions, "Ordinary Supermen," airdate June 8, 2008 (season 1)

- ↑ Zornio, Mary C. "Virgil Ivan "Gus" Grissom". NASA History Program Office. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

- ↑ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oFmNo8UFMjI YouTube

- ↑ French, F.; Burgess, C. (2007). Into That Silent Sea: Trailblazers of the Space Era, 1961-1965, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press (ISBN 978-0-8032-1146-9), 93

- ↑ Alexander, C. C.; Grimwood, J. M.; Swenson, L. S. Jr. (1966). "Chap. 14: Climax of Project Mercury-The Textbook Flight". This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury. NASA. p. 484. Retrieved 2009-08-23. (HTML copy Retrieved 2015-07-12)

- ↑ Banke, Jim (June 17, 2000). "Gus Grissom didn't sink the Liberty Bell 7 Mercury capsule". Space. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- ↑ "U.S. in Space". Year in Review. UPI.com. Retrieved 2015-07-12.

- ↑ The first person to reach space twice was Joseph A. Walker, a NASA test pilot who made two X-15 flights in 1963 which exceeded 100 kilometers (54 nmi) altitude, the internationally recognized definition of outer space.

- ↑ "Photo Paresev Contact Sheet". NASA Dryden Flight Research Center. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

- ↑ Hacker, Barton C.; James M. Grimwood (1977). On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini. NASA History Series #4203. NASA Special Publications. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ↑ Agle, D.C. (September 1, 1998), "Flying the Gusmobile", Air & Space, Smithsonian Institution

- ↑ Shayler, David (2001), Gemini: Steps to the Moon. Chichester, UK: Praxis Publishing. ISBN 1-85233-405-3, p. 186

- ↑ "To the Moon Transcript". NOVA. PBS. July 13, 1999. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- ↑ "Findings, Determinations And Recommendations". Report of Apollo 204 Review Board. NASA. April 5, 1967.

No single ignition source of the fire was conclusively identified.

- 1 2 White, Mary C. "Detailed Biographies of Apollo I Crew - Gus Grissom". NASA. Retrieved June 25, 2016.

- ↑ Slayton, Donald K; Cassutt, Michael (1994). Deke!: U.S. Manned Space from Mercury to the Shuttle (1st ed.). New York City: Forge: St. Martin's Press. pp. 223, 234. ISBN 0-312-85503-6. LCCN 94-2463. OCLC 29845663.

- ↑ Kelly, John (November 20, 2002). "Gus Grissom's Family, NASA Fight Over Spacesuit". Florida Today. Archived from the original on May 21, 2008. Retrieved May 27, 2007.

- ↑ "Luckless Gus Grissom in the hot seat again". RoadsideAmerica.com. November 24, 2002. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved May 4, 2007.

- ↑ Lee, Christopher (August 24, 2005). "Grissom Spacesuit in Tug of War". Washington Post. Retrieved May 27, 2007.

- ↑ "In Memoriam - Lt. Col. Virgil Ivan "Gus" Grissom (USAF)". Archived from the original on July 23, 2014.

- ↑ "40th Anniversary of Mercury 7: Virgil Ivan "Gus" Grissom".

- ↑ "International Space Hall of Fame :: New Mexico Museum of Space History :: Inductee Profile".

- ↑ "National Aviation Hall of fame: Our Enshrinees". National Aviation Hall of Fame. Retrieved February 10, 2011.

- ↑ "Virgil I. (Gus) Grissom - Astronaut Scholarship Foundation".

- ↑ "Space Foundation Survey Reveals Broad Range of Space Heroes".

- ↑ "Early Apollo". Apollo to the Moon: To Reach the Moon - Building a Moon Rocket. Smithsonian Institution, National Air and Space Museum. July 1999. Archived from the original on May 24, 2011. Retrieved April 3, 2011.

- ↑ "The Official Site of Edward White, II".

- ↑ Wasik, John W. (April 4, 1965). "Virgil Grissom and John Young: Our Trail-Blazing "Twin" Astronauts". Family Weekly. The Herald-Tribune. p. 4. Retrieved January 28, 2010.

- ↑ "Parks & Recreation: List of parks". City of Fullerton. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ↑ "Fallen Astronauts: Book Review".

- ↑ "City of Long Beach". Archived from the original on July 13, 2010.

- ↑ "DNR: Gus Grissom Memorial".

- ↑ "Questions About Grissom". Grissom Air Reserve Base, USAF. Archived from the original on November 3, 2007. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ↑ Sequin, Cynthia (October 14, 2005). "Purdue industrial engineering kicks off Grissom renovation, celebrates gifts". Purdue University News. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ↑ "Grissom High School". WikiMapia. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ↑ Jaques, Bob (June 6, 2002). "First spacewalk by American astronaut 37 years ago" (PDF). Marshall Star. NASA Marshall Space Flight Center. p. 5.

- ↑ "Welcome to Virgil Grissom Elementary School". Old Bridge Township Public Schools. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- ↑ "Grissom Elementary School". Tulsa Public Schools. Retrieved July 13, 2013.

- ↑ "Mission Control". Virgil I. Grissom Elementary School. Houston ISD. Retrieved July 27, 2009.

- ↑ Okuda, Michael (October 22, 2002). Star Trek III: The Search for Spock, Special Collector's Edition: Text commentary (DVD; Disc 1/2). Paramount Pictures.

- ↑ Roddenberry, Gene (May 1990). "The Most Toys". Star Trek: The Next Generation. Season 3. Episode 22.

- ↑ Berman, Rick (February 1999). "Field of Fire". Star Trek: Deep Space Nine. Season 7. Episode 13.

- ↑ Gabettas, Chris (Spring 2010). "William Petersen: From ISU to CSI". Idaho State University Magazine. 20 (2). Idaho State University. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ↑ Burgess, Colin (September 2015). Aurora 7: The Mercury Space Flight of M. Scott Carpenter. Springer Praxis Books. p. 232. ISBN 978-3-319-20438-3. Retrieved October 19, 2015.

- ↑ "Gus Grissom: The Lost Astronaut (Indiana Biography Series): Ray E. Boomhower, Kathleen M. Breen, Paula J. Corpuz: 9780871951762: Amazon.com: Books".

References

- Boomhower, Ray E. (2004). Gus Grissom: The Lost Astronaut. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. ISBN 0-87195-176-2.

- Burgess, Colin (2014). Liberty Bell 7 : the suborbital Mercury flight of Virgil I. Grissom. Cham: Springer-Praxis books in space exploration. ISBN 9783319043906. OCLC 868042180.

- Grissom, Virgil I. (1968). Gemini: A Personal Account of Man's Venture into Space. New York: MacMillan Publishing Company. ISBN 0-02-545800-0. OCLC 442293.

Further reading

- Beddingfield, Sam. "Astronaut Virgil "Gus" Grissom". SpySpace.

- IHS Staff. "Virgil "Gus" Grissom". Indiana Historical Society.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Gus Grissom. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Gus Grissom |

- Grissom's official NASA bio

- Detailed Biographies of Apollo I Crew - Gus Grissom - NASA

- Gus Grissom at Astronauts Memorial page

- Virgil I. Grissom Memorial at Spring Mill State Park (pdf-2.2 Mb)

- Gus Grissom at the Internet Movie Database

- Gus Grissom at Find a Grave