William O. Douglas

| William O. Douglas | |

|---|---|

| |

| Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States | |

|

In office April 15, 1939 – November 12, 1975[1] | |

| Nominated by | Franklin Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | Louis Brandeis |

| Succeeded by | John Paul Stevens |

| 3rd Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission | |

|

In office August 17, 1937 – April 15, 1939 | |

| President | Franklin Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | James Landis |

| Succeeded by | Jerome Frank |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

William Orville Douglas October 16, 1898 Maine Township, Minnesota, U.S. |

| Died |

January 19, 1980 (aged 81) Bethesda, Maryland, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse(s) |

Mildred Riddle (1923–1953) Joan Martin (1963–1966) Cathleen Heffernan (1966–1980) |

| Alma mater |

Whitman College Columbia University |

| Religion | Presbyterianism |

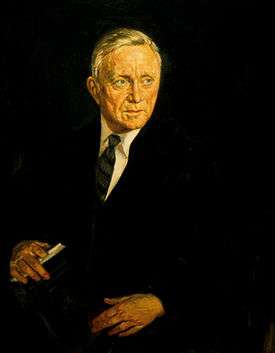

William Orville Douglas (October 16, 1898 – January 19, 1980) was an American jurist and politician who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Nominated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Douglas was confirmed at the age of 40, one of the youngest justices appointed to the court. His term, lasting 36 years and 209 days (1939–75), is the longest term in the history of the Supreme Court.

Douglas holds a number of records as a Supreme Court Justice, including the most opinions. He was the 79th person appointed and confirmed to the bench of that court. In 1975 Time magazine called Douglas "the most doctrinaire and committed civil libertarian ever to sit on the court".[2]

Early life and education

Douglas was born in 1898 in Maine Township, Otter Tail County, Minnesota, the son of Julia Bickford (Fisk) and William Douglas, an itinerant Scottish Presbyterian minister from Pictou County, Nova Scotia.[3][4] His family moved to California, and then to Cleveland, Washington. At age two Douglas suffered through an intestinal colic, which Douglas would claim had been polio.[5] His mother attributed his recovery to a miracle, telling Douglas that one day he would be President of the United States.[6]

His father died in Portland, Oregon, in 1904, when Douglas was six years old. Douglas would later claim his mother had been left destitute.[5] After moving the family from town to town in the West, his mother, with three young children, settled with them in Yakima, Washington. William, like the rest of the Douglas family, worked at odd jobs to earn extra money, and a college education appeared to be unaffordable. He was the valedictorian at Yakima High School and did well enough in school to earn a scholarship to Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington.[7]

While at Whitman, Douglas became a member of Beta Theta Pi fraternity. He worked at various jobs while attending school, including as a waiter and janitor during the school year, and at a cherry orchard in the summer. Picking cherries, Douglas would say later, inspired him to a legal career. He once said of his early interest in the law:

I worked among the very, very poor, the migrant laborers, the Chicanos and the I.W.W's who I saw being shot at by the police. I saw cruelty and hardness, and my impulse was to be a force in other developments in the law.[8]

Douglas was elected Phi Beta Kappa,[9] participated on the debate team, and was elected as student body president in his final year. After graduating in 1920 with a B.A. in English and economics, he taught English and Latin at Yakima high schools for the next two years, hoping to earn enough to attend law school. "Finally," he said, "I decided it was impossible to save enough money by teaching and I said to hell with it."[7]

He traveled to New York (taking a job tending sheep on a Chicago-bound train, in return for free passage), with hopes to attend the Columbia Law School.[7] Douglas drew on his Beta Theta Pi membership to help him survive in New York, as he stayed at one of its houses and was able to borrow $75 from a fraternity brother from Washington, enough to enroll at Columbia.[10]

Six months later, Douglas' funds were running out. The appointments office at the law school told him that a New York firm wanted a student to help prepare a correspondence course for law. Douglas earned $600 for his work, enabling him to stay in school. Hired for similar projects, he saved $1,000 by semester's end.[10] His wife Mildred worked as a schoolteacher to support him throughout law school, which he would later conceal by lying about the year they were married.[6] He graduated fifth in his class in 1925, although he later claimed to have been second.[6]

Douglas traveled to La Grande, Oregon, to marry Mildred Riddle, whom he had known in Yakima. After their return to New York, he started work at the firm of Cravath, DeGersdorff, Swaine and Wood (later Cravath, Swaine & Moore).[11][12]:p. 54

Yale and the SEC

Douglas quit the Cravath firm after four months. After one year, he moved back to Yakima, but soon regretted the move and never practiced law in the state. After a time of unemployment and another months-long stint at Cravath, he started teaching at Columbia Law School.

Douglas later joined the faculty of Yale Law School. There he became an expert on commercial litigation and bankruptcy, and was identified with the legal realist movement. This pushed for an understanding of law based less on formalistic legal doctrines and more on the real-world effects of the law. While teaching at Yale, he and fellow professor Thurman Arnold were riding the New Haven Railroad and were inspired to set the sign Passengers will please refrain... to Antonín Dvořák's Humoresque #7.[13] Robert Maynard Hutchins described Douglas as “the most outstanding law professor in the nation”.[14] When Hutchings became president of the University of Chicago, Douglas accepted an offer to move there, which he backed out of once he was made a Sterling Professor at Yale.[6]

Politics and government

In 1934, Douglas left Yale to join the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in a political appointee position, having been nominated by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.[15] By 1937, he had become an adviser and friend to the President and the SEC chairman.

During this time, Douglas became friends with a group of young New Dealers, including Tommy "The Cork" Corcoran and Abe Fortas. He was also close, socially and in thinking, with the Progressives of the era, such as Philip and Robert La Follette, Jr., and later with President Kennedy. This social/political group befriended Lyndon Baines Johnson, a freshman Congressman from the 10th District of Texas. In his book The Years of Lyndon Johnson: The Path to Power, Robert Caro writes that in 1937, Douglas helped persuade President Roosevelt to authorize the Marshall Ford Dam, a controversial project whose approval enabled Johnson to consolidate his power as a congressman.[16]

Supreme Court

In 1939, Justice Louis D. Brandeis retired from the Court, and Roosevelt nominated Douglas as his replacement on March 20.[15] Douglas was Justice Louis Brandeis's personal choice of a successor.[6] Douglas later revealed that this had been a great surprise to him—Roosevelt had summoned him to an "important meeting," and Douglas feared that he was to be named as the chairman of the Federal Communications Commission. He was confirmed by the United States Senate on April 4 by a vote of 62 to 4. The four negative votes were all cast by Republicans: Lynn J. Frazier, Henry Cabot Lodge Jr., Gerald P. Nye, and Clyde M. Reed. Douglas was sworn into office on April 17, 1939. At the age of forty, Douglas was one of the youngest justices to be confirmed to the Supreme Court.[17]

Relationships with others at Supreme Court

Douglas was often at odds with fellow Justice Felix Frankfurter, who believed in judicial restraint and thought the court should stay out of politics.[15] Douglas did not highly value judicial consistency or stare decisis when deciding cases.[15]

Judge Richard A. Posner, who was a law clerk at the Court during the latter part of Douglas's tenure, characterized him as "a bored, distracted, uncollegial, irresponsible" Supreme Court justice, as well as "rude, ice-cold, hot-tempered, ungrateful, foul-mouthed, self-absorbed" and so abusive in "treatment of his staff to the point where his law clerks—whom he described as 'the lowest form of human life'—took to calling him "shithead" behind his back." Posner asserts also that "Douglas's judicial oeuvre is slipshod and slapdash." Yet, says Posner, Douglas's "intelligence, his energy, his academic and government experience, his flair for writing, the leadership skills that he had displayed at the SEC, and his ability to charm when he bothered to try" could have let him "become the greatest justice in history."[6]

Judicial philosophy

In general, legal scholars have noted that Douglas' judicial style was unusual in that he did not attempt to elaborate justifications for his judicial positions on the basis of text, history, or precedent. Douglas was known for writing short, pithy opinions which relied on philosophical insights, observations about current politics, and literature, as much as more conventional "judicial" sources. Douglas wrote many of his opinions in twenty minutes, often publishing the first draft.[14] Regardless, Douglas was known for his fearsome work ethic, publishing over thirty books and once telling an exhausted secretary (Fay Aull) "If you hadn't stopped working, you wouldn't be tired".[14]

Douglas frequently disagreed with the other justices, dissenting in almost 40% of cases, more than half of the time writing only for himself.[14] Ronald Dworkin would conclude that because Douglas believed his convictions were merely “a matter of his own emotional biases”, Douglas would fail to meet “minimal intellectual responsibilities”.[18] Ultimately, Douglas believed that a judge's role was "not neutral." "The Constitution is not neutral. It was designed to take the government off the backs of the people ...."[19]

On the bench Douglas became known as a strong advocate of First Amendment rights. With fellow Justice Hugo Black, Douglas argued for a "literalist" interpretation of the First Amendment, insisting that the First Amendment's command that "no law" shall restrict freedom of speech should be interpreted literally. He wrote the opinion in Terminiello v. City of Chicago (1949), overturning the conviction of a Catholic priest who allegedly caused a "breach of the peace" by making anti-Semitic comments during a raucous public speech. Douglas, joined by Black, furthered his advocacy of a broad reading of First Amendment rights by dissenting from the Supreme Court's decision in Dennis v. United States (1952), affirming the conviction of the leader of the U.S. Communist Party.

In 1944 Douglas voted with the majority to uphold the wartime internment of Japanese Americans, in Korematsu v. United States but, over the course of his career, he grew to become a leading advocate of individual rights. Suspicious of majority rule as it related to social and moral questions, he frequently expressed concern in his opinions at forced conformity with "the Establishment". For example, Douglas wrote the Opinion of the Court in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), explaining that a new constitutional right to privacy forbid state contraception bans because “specific guarantees in the Bill of Rights have penumbras, formed by emanations from those guarantees that help give them life and substance.”[15][20] This went too far for his old ally Black, who dissented in Griswold. Scholars have derided Douglas's reasoning and Justice Clarence Thomas would years later hang a sign in his chambers reading “Please don’t emanate in the penumbras”.[14]

Douglas and Black also disagreed in Fortson v. Morris (1967), which cleared the path for the Georgia State Legislature to choose the governor in the deadlocked 1966 race between Democrat Lester Maddox and Republican Howard Callaway. Whereas Black voted with the majority under strict construction to uphold the state constitutional provision, Douglas and Abe Fortas dissented. According to Douglas, Georgia tradition would guarantee a Maddox victory but he had trailed Callaway by some 3,000 votes in the general election returns. Douglas also saw the issue as a continuation of the earlier decision Gray v. Sanders, which had struck down Georgia's County Unit System, a kind of electoral college formerly used to choose the governor.

Rosenberg Case

On June 17, 1953, Douglas granted a temporary stay of execution to Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, who had been convicted of selling the plans for the atomic bomb to the Soviet Union during the Cold War. The basis for the stay was that the Rosenbergs had been sentenced to die by Judge Irving Kaufman without the consent of the jury. While this was permissible under the Espionage Act of 1917, under which the Rosenbergs were tried, a later law, the Atomic Energy Act of 1946, held that only the jury could pronounce the death penalty. Since at the time the stay was granted the Supreme Court was out of session, this stay meant that the Rosenbergs could expect to wait at least six months before the case was heard.

When Attorney General Herbert Brownell heard about the stay, however, he immediately took his objection to Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson, who reconvened the Court before the appointed date and set aside the stay. Douglas had departed for vacation, but on learning of the special session of the Court, he returned to Washington.[12] Because of widespread opposition to his decision, Douglas briefly faced impeachment proceedings in Congress, but attempts to remove him from the Court went nowhere.[21]

Vietnam War

Justice Douglas took strong positions on the Vietnam War. In 1952 Douglas traveled to Vietnam and met with Ho Chi Minh. During the trip Douglas became friendly with Ngo Dinh Diem and in 1953 he personally introduced the nationalist leader to Senators Mike Mansfield and John F. Kennedy. Douglas became one of the chief promoters for U.S. support of Diem, with CIA Deputy Director Robert Amory crediting Diem becoming "our man in Indochina" to a conversation with Douglas during a party at Martin Agronsky’s house.[22][22]

After Diem’s assassination in 1963 Douglas became strongly critical of the war, believing Diem had been killed because he “was not sufficiently servile to Pentagon demands.”[22] Douglas now outspokenly argued the war was illegal, dissenting whenever the Court passed on an opportunity to hear such claims.[23] In 1968 Douglas issued an order blocking the shipment of Army reservists to Vietnam, before the eight other justices unanimously reversed him.[22]

In Schlesinger v. Holtzman (1973) Justice Thurgood Marshall issued an in-chambers opinion declining a Congresswoman's request for a court order stopping the military from bombing Cambodia.[24] The Court was in recess for the summer but the Congresswoman reapplied, this time to Douglas.[22] Justice Douglas met with the Congresswoman’s ACLU lawyers at his home in Goose Prairie, Washington and promised them a hearing the next day.[22] On Friday, August 3, 1973, Douglas held a hearing in the Yakima federal courthouse, where he dismissed the Government’s argument that he was causing a “constitutional confrontation” by saying, “we live in a world of confrontations. That’s what the whole system is about.”[22] On August 4, Douglas ordered the military to stop bombing, reasoning “denial of the application before me would catapult our airmen as well as Cambodian peasants into the death zone.”[25]

The U.S. military ignored the new Supreme Court order.[24] Six hours later the eight other justices reconvening by telephone for a special term and unanimously overturned Douglas’s ruling.[26]

"Trees have standing"

In his dissenting opinion in the landmark environmental law case, Sierra Club v. Morton, 405 U.S. 727 (1972), Justice Douglas argued that "inanimate objects" should have standing to sue in court:

The critical question of "standing" would be simplified and also put neatly in focus if we fashioned a federal rule that allowed environmental issues to be litigated before federal agencies or federal courts in the name of the inanimate object about to be despoiled, defaced, or invaded by roads and bulldozers and where injury is the subject of public outrage. Contemporary public concern for protecting nature's ecological equilibrium should lead to the conferral of standing upon environmental objects to sue for their own preservation. This suit would therefore be more properly labeled as Mineral King v. Morton.[27]

He continued:

Inanimate objects are sometimes parties in litigation. A ship has a legal personality, a fiction found useful for maritime purposes. The corporation sole—a creature of ecclesiastical law—is an acceptable adversary and large fortunes ride on its cases .... So it should be as respects valleys, alpine meadows, rivers, lakes, estuaries, beaches, ridges, groves of trees, swampland, or even air that feels the destructive pressures of modern technology and modern life. The river, for example, is the living symbol of all the life it sustains or nourishes—fish, aquatic insects, water ouzels, otter, fisher, deer, elk, bear, and all other animals, including man, who are dependent on it or who enjoy it for its sight, its sound, or its life. The river as plaintiff speaks for the ecological unit of life that is part of it.[27]

Environmentalism

In the early 1970s, Douglas and his wife Cathleen were invited by Neil Compton and the Ozark Society to visit and canoe down part of the free-flowing Buffalo River in Arkansas. They put in at the low water bridge at Boxley. This experience made him a fan of the river and the young organization's idea of protecting it. Douglas was instrumental in having the Buffalo preserved as a free-flowing river, left in its natural state.[28] This decision was opposed by the region's Corps of Army Engineers. The act that soon followed designated the Buffalo River as America's first National River.[29]

Douglas was a self-professed outdoorsman. According to The Thru-Hiker's Companion, a guide published by the Appalachian Long Distance Hikers Association, Douglas hiked the entire 2,000 miles (3,200 km) trail from Georgia to Maine.[30] His love for the environment carried through to his judicial reasoning.

In his autobiographical Of Men and Mountains (1950), Douglas discusses his close childhood connections with nature.[31]

He served on the Board of Directors of the Sierra Club from 1960 to 1962 and wrote prolifically on his love of the outdoors. He is credited with saving the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal and inspiring the effort to establish the right-of-way as a national park. As it was being discussed, he challenged the editorial board of The Washington Post to go with him for a walk on the canal after the newspaper had published opinions supporting Congress's plan to fill and pave the canal into a road.[32] His efforts convinced the editorial board to change its stance and helped save the park.[32]

In 1962, Douglas wrote a glowing review of Rachel Carson's book, Silent Spring, which was included in the widely read Book-of-the-Month Club edition. He later swayed the Court to preserve the Red River Gorge in eastern Kentucky, when a proposal to build a dam and flood the gorge reached the Court. Douglas personally visited the area on November 18, 1967. The Red River Gorge's Douglas Trail is named in his honor.

In 1969 he wrote Points of Rebellion and published an essay in Evergreen magazine. Two years later, Justice Douglas helped launch the nation's first law review dedicated solely to environmental issues by publishing a paper in Lewis & Clark Law School's new law review, Environmental Law.

Due to Douglas' active role in advocating the preservation and protection of wilderness across the United States, he was nicknamed "Wild Bill." Douglas was a friend and frequent guest of Harry Randall Truman, owner of the Mount St. Helens Lodge at Spirit Lake in Washington.

Honors

- The 1984 Washington Wilderness Act designated the Cougar Lake Roadless area as the William O. Douglas Wilderness. This wilderness, which adjoins Mount Rainier National Park in Washington State, is named in his honor.[33]

- Douglas Falls in the Appalachian Mountains of North Carolina, is named for him.

- The William O. Douglas Outdoor Classroom in Beverly Hills, California, is named for him.

- He was elected to the Ecology Hall of Fame for his dedication to conservation.

- The William O. Douglas Honors College at Central Washington University in Ellensburg, Washington, is named for him.

- The William O. Douglas Federal Building, an historic post office, courthouse, and federal office building in Yakima, Washington, which is listed in the National Register of Historic Places, was renamed in his honor in 1978.

Presidential politics

When, in early 1944, President Franklin D. Roosevelt decided not to support the renomination of Vice President Henry A. Wallace at the party's national convention, a short list of possible replacements was drafted. The names on the list included former Senator and Supreme Court Justice James F. Byrnes of South Carolina, former Senator (and future Supreme Court justice) Sherman Minton, former Governor and High Commissioner to the Philippines Paul McNutt of Indiana, House Speaker Sam Rayburn of Texas, Senator Alben W. Barkley of Kentucky, Senator Harry S. Truman of Missouri, and Douglas.

Five days before the vice presidential nominee was to be chosen at the convention, on July 15, Committee Chairman Robert E. Hannegan received a letter from Roosevelt stating that his choice for the nominee would be either "Harry Truman or Bill Douglas." After Hannegan released the letter to the convention on July 20, the nomination went without incident, and Truman was nominated on the second ballot. Douglas received two votes on the second ballot and none on the first.

After the convention, Douglas' supporters spread the rumor that the note sent to Hannegan had read "Bill Douglas or Harry Truman," not the other way around.[34] These supporters claimed that Hannegan, a Truman supporter, feared that Douglas' nomination would drive southern white voters away from the ticket (Douglas had a strong anti-segregation record on the Supreme Court) and had switched the names to suggest that Truman was Roosevelt's real choice.[34]

By 1948, Douglas' presidential aspirations were rekindled by Truman's low popularity, after he had succeeded Roosevelt in 1945. Many Democrats, believing that Truman could not be elected in November, began trying to find a replacement candidate. Attempts were made to draft popular retired war hero General Dwight D. Eisenhower for the nomination. A "Draft Douglas" campaign, complete with souvenir buttons and hats, sprang up in New Hampshire and several other primary states. Douglas campaigned for the nomination for a short time, but he soon withdrew his name from consideration.

In the end, Eisenhower refused to be drafted, and Truman won nomination easily. Although Truman approached Douglas about the vice presidential nomination, the Justice turned him down. Douglas' close associate Tommy Corcoran was later heard to ask, "Why be a number two man to a number two man?"[35] Truman selected Senator Alben W. Barkley and the two won the election.

Impeachment attempts

Political opponents made two attempts to remove Douglas from the Supreme Court, both unsuccessful.

Rosenberg case

On June 17, 1953, Representative William M. Wheeler of Georgia, infuriated by Douglas' brief stay of execution in the Rosenberg case, introduced a resolution to impeach the Justice. The resolution was referred the next day to the Judiciary Committee to investigate the charges. On July 7, 1953 the committee voted to end the investigation.

1970 Attempt

Justice Douglas maintained a busy speaking and publishing schedule to supplement his income. He became severely burdened financially due to a bitter divorce and settlement with his first wife. He gained additional financial difficulties after divorces and settlements with his second and third wives.

Douglas became president of the Parvin Foundation. His ties with the foundation (which was financed by the sale of the infamous Flamingo Hotel by casino financier and foundation founder Albert Parvin) became a prime target for then-House Minority Leader Gerald R. Ford. Besides being personally disgusted by Douglas' lifestyle, Representative Ford was also mindful that Douglas protégé Abe Fortas was forced to resign because of ties to a similar foundation.[36] Fortas would later say that he "resigned to save Douglas," thinking that the dual investigations of himself and Douglas would stop with his resignation.[36]

Some scholars[37][38] have argued that Ford's impeachment attempt was politically motivated. Those who support this contention note Ford's well-known disappointment with the Senate over the failed nominations of Clement Haynsworth and G. Harrold Carswell to succeed Fortas. In April 1970, Congressman Ford moved to impeach Douglas in an attempt to hit back at the Senate. House Judiciary Chairman Emanuel Celler handled the case carefully and there did not appear to be evidence of any criminal conduct on the part of Douglas. (Attorney General John N. Mitchell and the Nixon administration worked to gather evidence to the contrary.)[39] Congressman Ford moved forward in the first major attempt to impeach a Supreme Court Justice in the modern era.

The hearings began in late April 1970. Congressman Ford was the main witness, and attacked Douglas' "liberal opinions"; his "defense of the 'filthy' film," the controversial Swedish film I Am Curious (Yellow) (1970); and his ties with the aforementioned Parvin. Douglas was also criticized for accepting $350 for an article he wrote on folk music in the magazine Avant Garde. The magazine's publisher had served a prison sentence for the distribution of another magazine in 1966 that had been deemed pornographic by some critics. Describing Douglas' article, Ford stated, "The article itself is not pornographic, although it praises the lusty, lurid, and risqué along with the social protest of left-wing folk singers." Ford also attacked Douglas for publishing an article in Evergreen Review, which he claimed was known to publish photographs of naked women. The Republican congressmen, however, refused to give the majority Democrats copies of the magazines described, prompting Congressman Wayne Hays to remark "Has anybody read the article – or is everybody over there who has a magazine just looking at the pictures?"[40]

As it became clear that the impeachment proceedings would be unsuccessful, they were brought to a close and no public vote on the matter was taken.[41]

Around this time, Douglas came to believe that strangers snooping around his Washington home were FBI agents, attempting to plant marijuana to entrap him. In a private letter to his neighbors, he said: "I wrote you last fall or winter that federal agents were in Yakima and Goose Prairie looking me over at Goose Prairie. I thought they were merely counting fence posts. But I learned in New York City yesterday that they were planting marijuana with the prospect of a nice big TV-covered raid in July or August. I forgot to tell you that this gang in power is not in search of truth. They are 'search and destroy' people."[42]

Judicial record-setter

During his tenure on the Supreme Court, Justice Douglas set a number of records, all of which stand. He sat on the U.S. Supreme Court for more than thirty-six years (1939–75), longer than any other Justice. During those years, he wrote some thirty books in addition to his opinions and dissenting opinions. He gave more speeches than any other Justice, and his record for sidebar productivity is unlikely ever to be topped. Douglas also holds the record among Justices for having had the most wives (four) and the most divorces (three) while on the bench.[14]

Nicknames

During his time on the Supreme Court, Douglas picked up a number of nicknames from both admirers and detractors. The most common epithet was "Wild Bill", which was in reference to his independent and often unpredictable stances and cowboy-style mannerisms—although many of the latter were considered by some to be affectations for the consumption of the press.[12]

Retirement

Since the 1970 impeachment hearings, Douglas had wanted to retire from the court. He wrote to his friend and former student Abe Fortas: "My ideas are way out of line with current trends, and I see no particular point in staying around and being obnoxious".[36]

At age 76 on December 31, 1974, while on vacation with his wife Cathleen in the Bahamas, Douglas suffered a debilitating stroke in the right hemisphere of his brain. It paralyzed his left leg and forced him to use a wheelchair. Douglas, severely disabled, insisted on continuing to participate in Supreme Court affairs despite his obvious incapacity. Seven of his fellow justices voted to postpone until the next term any argued case in which Douglas' vote might make a difference.[43] At the urging of Fortas, Douglas finally retired on November 12, 1975, after 36 years of service.

Douglas' formal resignation was submitted, as required by Federal protocols, to his long-time political nemesis, and then President, Gerald Ford. In his response, Ford put aside previous differences, and paid tribute to the retiring justice, writing:

"May I express on behalf of all our countrymen this nation's great gratitude for your more than thirty-six years as a member of the Supreme Court. Your distinguished years of service are unequaled in all the history of the Court."[44]

Ford also hosted Justice Douglas and his wife Cathleen as honored guests at a White House state dinner later that same month, writing of the occasion later: "We had had differences in the past, but I wanted to stress that bygones were bygones."[45]

Douglas maintained that he could assume judicial senior status on the Court, and attempted to continue serving in that capacity, according to Woodward and Armstrong, and refused to accept his retirement, trying to participate in the Court's cases well into 1976, after John Paul Stevens had taken his former seat.[46] Douglas reacted with outrage when, returning to his old chambers, he discovered that his clerks had been reassigned to Stevens, and when he tried to file opinions in cases whose arguments he had heard before his retirement. Chief Justice Warren Burger ordered all justices, clerks, and other staff members to refuse help to Douglas in those efforts. When Douglas tried in March 1976 to hear arguments in a capital-punishment case, Gregg v. Georgia, the nine sitting justices signed a formal letter informing him that his retirement had ended his official duties on the court. Only then did Douglas withdraw from Supreme Court business.[47] One commentator has attributed some of his behavior after his stroke to anosognosia, a neuropsychological presentation which leads an affected person to be unaware and unable to acknowledge disease in himself. It often results in defects in reasoning, decision making, emotions, and feeling.[48]

Personal life

Douglas' first wife was Mildred Riddle, a teacher at North Yakima High School six years his senior, whom he married on August 16, 1923. They had two children, Mildred and William Jr.[49] They were divorced on July 20, 1953. Douglas would not hear about Mildred’s death in 1969 because his children had stopped talking to him.[14] William Douglas Jr. became an actor, playing Gerald Zinser in PT 109.

On October 2, 1949, Douglas had thirteen of his ribs broken after he was thrown from a horse and tumbled down a rocky hillside.[50] Due to his injuries, Douglas did not return to the court until March 1950,[51] or take part in many of that term's cases.[52] Four months after his return to the court, Douglas had to be hospitalized again due to his being kicked by a horse.[12][53]

Douglas began openly pursuing Mercedes Davidson in 1951.[14] Other justices at the time kept mistresses as secretaries or kept them away from the Court building, according to Douglas's messenger Harry Datcher, but Douglas "did what he did in the open. He didn’t give a damn what people thought of him."[14] He divorced Mildred in 1953. Douglas's former friend Thomas Gardiner Corcoran represented Mildred in the divorce, securing alimony with an "escalator clause" that financially motivated Douglas to publish more books.[6] On December 14, 1954, Douglas married his second wife, Mercedes (née Hester), the divorced wife of a former Assistant Secretary of the Interior.[54] They divorced nine years later in 1963.

In 1961 Douglas pursued Joanie Martin, an Allegheny College student writing her thesis on him.[14] At the age of nearly 65, Douglas married for the third time, to Joan, then 23 years old, on August 5, 1963.[55] Douglas and Joanie divorced in 1966.

On July 15, 1966, Douglas married Cathleen Heffernan, then a 22-year-old student at Marylhurst College.[56] They met when he was vacationing at Mount St. Helens Lodge, a mountain wilderness lodge in Washington state at Spirit Lake, where she was working for the summer as a waitress,[57] and remained together until his death in 1980.[58] Their age difference was a subject of national controversy at the time of their marriage.[59]

For much of his life, Douglas was dogged by various rumors and allegations about his private life, originating from political rivals and other detractors of his liberal legal opinions on the Court—often a matter of controversy. In one such instance in 1966, Republican Senator Robert Dole of Kansas compared his court decisions to his "bad judgment from a matrimonial standpoint", and several other Republican Members of Congress introduced resolutions in the House of Representatives, though none ever passed, that called for investigation of Douglas' moral character.[57]

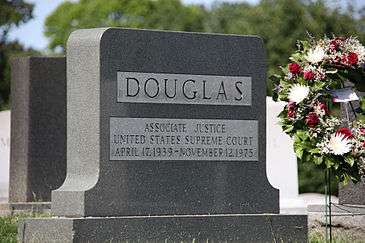

Death

Four years after retiring from the Supreme Court, William O. Douglas died at age 81 on January 19, 1980, at Walter Reed Hospital in Washington DC. He was survived by his fourth wife, Cathleen "Cathy" Douglas, and two children, Mildred and William Jr., from his first wife.

Douglas is interred in Section 5 of Arlington National Cemetery, near the graves of eight other former Supreme Court Justices: Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., Warren E. Burger, William Rehnquist, Hugo Black, Potter Stewart, William J. Brennan, Thurgood Marshall, and Harry Blackmun.[60][61] Throughout his life Douglas claimed he had been a U.S. Army private, which was inscribed on his headstone. Some historians, including biographer Bruce Murphy, asserted that this claim was false,[5][6][12] although Murphy later added, according to Washington Post editorial writer Charles Lane, that Douglas's "career on the court makes it 'appropriate' " that he be buried in Arlington Cemetery.[62]

Lane engaged in further research, consulting applicable provisions of the federal statutes, locating Douglas's honorable discharge. and speaking with Arlington Cemetery staff. Records in the Library of Congress showed that from June to December 1918, Douglas served in what the War Department's regulations termed "a soldier in the Army of the United States. . . placed upon active-duty status immediately." Tom Sherlock, Arlington's official historian, told Lane that an "active-duty recruit whose service was limited to boot camp [in which Douglas served] would qualify" to be buried in Arlington. Lane therefore concluded, "Legally, then, Douglas may have had a plausible claim to be a 'Private, U.S. Army,' as his headstone at Arlington reads."[63]

Legacy and honors

- Since 1972, the William O. Douglas Committee, a select group of law students at Gonzaga University in Spokane, Washington has sponsored a series of lectures on the First Amendment in Douglas's honor.[64] Douglas was the first speaker for the annual series.[64]

- The honors college at Central Washington University in Ellensburg, Washington was named for Douglas.

- In 1977, a bust of Douglas was erected along the towpath of the C & O Canal in Georgetown in Washington, DC, and the C & O Canal National Historical Park was officially dedicated to Douglas in honor of his exhaustive efforts dating from the 1950s in support of preserving the historic canal.[65]

- A statue of Douglas was installed at A.C. Davis High School, in Yakima, Washington. It was dedicated in 1978 to Douglas when the new school was opened.

- 1978, in Yakima, the William O. Douglas Federal Building was named for him.

- William O. Douglas Hall was named in his honor at his alma mater, Whitman College.

- Douglas Hall, apartments for continuing students at Earl Warren College, at the University of California, San Diego, is named for him as well.

- In 1998, the C&O Canal National Historical Park commemorated the 100th Anniversary of Douglas' birth by unveiling a portrait of Justice Douglas hiking along the towpath by artist Tom Kozar. The portrait, commissioned by the C&O Canal Association, now hangs in the Great Falls Tavern Visitor Center in the National Historical Park, which was officially dedicated to Douglas in 1977.[66]

Theater

Mountain-The Journey of Justice Douglas is a play written by Douglass Scott which explores the life of William O. Douglas.[67]

Bibliography

The papers of William O. Douglas from his career as professor of law, Securities and Exchange commissioner, and associate justice of the United States Supreme Court were bequeathed by him to the Library of Congress.[68]

- Go East, Young Man: The Early Years; The Autobiography of William O. Douglas ISBN 0-394-71165-3

- The Court Years, 1939 to 1975: The Autobiography of William O. Douglas ISBN 0-394-49240-4

- "Mr. Lincoln & the Negroes: The Long Road to Equality", 1963, Atheneum Press, New York. LoC card catalog number 63-17851

- Democracy and finance: The addresses and public statements of William O. Douglas as member and chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission ISBN 0-8046-0556-4

- Nature's Justice: Writings of William O. Douglas ISBN 0-87071-482-1

- Strange Lands and Friendly People, by William O. Douglas ISBN 1-4067-7204-6

- West of the Indus, by William O. Douglas, 1958, ASIN B0007DMD1O

- Beyond the High Himalayas, by William O. Douglas, 1952, ISBN 112112979X

- North From Malaya, by William O. Douglas ASIN B000UCP8IW

- Points of Rebellion, by William O. Douglas ISBN 0-394-44068-4

- An Interview with William O. Douglas by William O. Douglas (sound recording) ASIN B000S592XI

- An Interview with William O. Douglas, Folkway Records FW 07350

- The Mike Wallace Interview, with Mike Wallace May 11, 1958 (video)

- The Mike Wallace Interview, May 11, 1958 (transcript)

See also

References

- ↑ "Members of the Supreme Court of the United States". Supreme Court of the United States. Retrieved April 21, 2010.

- ↑ "The Law: The Court's Uncompromising Libertarian". Time.com. 1975-11-24. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- ↑ . Ernest Kerr, Imprint of the Maritimes, 1959, Boston: Christopher Publishing, p. 83.

- ↑ "William O. Douglas: 1939–1975 : SAGE Knowledge". Knowledge.sagepub.com. 2013-05-22. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- 1 2 3 Ryerson, James (13 April 2003). "Dirty Rotten Hero". The New York Times. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Richard A. Posner, The Anti-Hero", The New Republic (Feb. 24, 2003).

- 1 2 3 Current Biography 1941, pp233–235

- ↑ Whitman, Alden. (1980). "Vigorous Defender of Rights," The New York Times, 20 January 1980, p. 28.

- ↑ Supreme Court Justices Who Are Phi Beta Kappa Members, Phi Beta Kappa website, accessed Oct 4, 2009.

- 1 2 Current Biography 1941, p234

- ↑ Swain, Robert T. The Cravath Firm and Its Predecessors, 1819-1947, Volume 1 The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. orig. pub. 1946-1948 p. xv.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bruce Allen Murphy, Wild Bill: The Legend and Life of William O. Douglas, pp. 324–325 (New York: Random House, 2003).

- ↑ "Lyr Add: Humoresque (various versions)". Mudcat.org. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Garrow, David J. (27 March 2003). "The Tragedy of William O. Douglas". The Nation. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Christopher L. Tomlins (2005). The United States Supreme Court. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 475–476. ISBN 978-0-618-32969-4. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ↑ Christopher L. Tomlins (2005). The United States Supreme Court. Houghton Mifflin. p. 461. ISBN 978-0-618-32969-4. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ↑ Bowles, Nigel (1993). The Government and Politics of the United States (second ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 188. ISBN 0-312-10207-0.

- ↑ Dworkin, Ronald (19 February 1981). "Dissent on Douglas". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved 1 May 2016.

- ↑ Douglas, William O. (1980). The Court Years. Random House. p. 8.

- ↑ Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965)

- ↑ "House Move to Impeach Douglas Bogs Down; Sponsor Is Told He Fails to Prove His Case," The New York Times, Wednesday, July 1, 1953, p. 18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Moses, James L.. 1996. “William O. Douglas and the Vietnam War: Civil Liberties, Presidential Authority, and the "Political Question"”. Presidential Studies Quarterly 26 (4). [Wiley, Center for the Study of the Presidency and Congress]: 1019–33.

- ↑ Holtzman v. Schlesinger, 414 U.S. 1316 (1973) (Douglas, J., in chambers) citing Sarnoff v. Shultz, 409 U.S. 929; DaCosta v. Laird, 405 U. S. 979; Massachusetts v. Laird, 400 U. S. 886; McArthur v. Clifford, 393 U. S. 1002; Hart v. United States, 391 U. S. 956; Holmes v. United States, 391 U. S. 936; Mora v. McNamara, 389 U. S. 934, 935; Mitchell v. United States, 386 U. S. 972.

- 1 2 Eugene R. Fidell, Why Did the Cambodia Bombing Continue?, 13 GREEN BAG 2D 321 (2010).

- ↑ Holtzman v. Schlesinger, 414 U.S. 1316 (1973) (Douglas, J., in chambers).

- ↑ Schlesinger v. Holtzman, 414 U.S. 1321, 1322 (1973) (Douglas, J., dissenting in chambers).

- 1 2 Sierra Club v. Morton, 405 U.S. 727, 741–43 (USSC 1972).

- ↑ Blevins, Brooks (2001). Hill Folks: A History of Arkansas Ozarkers and Their Image. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. p. 235. ISBN 0-8078-5342-9.

- ↑ The Ozarks Society newsletters, and books by Kenneth L. Smith.

- ↑ Appalachian Trail Long Distance Hikers Association (2009). Appalachian Trail Thru-Hikers' Companion (2009) (2009 ed.). Harpers Ferry, WV: Appalachian Trail Conservancy. p. 122. ISBN 1-889386-60-X.

- ↑ Frederick, John J. (1950). "Speaking of Books : About Fables and Mountains ... Hogs and Government ... Animals and IQ's". The Rotarian. Rotary International. 77 (1): 39–40. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- 1 2 Lynch, John A. "Justice Douglas, the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal, and Maryland Legal History". University of Baltimore Law Forum. 35 (Spring 2005): 104–125.

- ↑ "Gifford Pinchot National Forest - Home". Fs.fed.us. Retrieved 2013-04-22.

- 1 2

- ↑ Simon, James F. (1980). Independent Journey: The Life of William O. Douglas (first ed.). New York: Harper & Row. p. 274. ISBN 0-06-014042-9.

- 1 2 3 Laura Kalman (1990). Abe Fortas. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-04669-4. Retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ↑ Gerhardt, Michael J. (2000). The Federal Impeachment Process. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-28956-7.

- ↑ Lohthan, William C. (1991). The United States Supreme Court: Lawmaking in the Third Branch of Government. Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-933623-2.

- ↑ Archived September 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "(DV) Gerard: Conservatives, Judicial Impeachment, and Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas". Dissidentvoice.org. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- ↑ The Federal Impeachment Process: A Constitutional and Historical Analysis - Michael J. Gerhardt. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- ↑ https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/lifestyle/1987/11/17/laying-the-gorbachev-groundwork/92c8d204-7f7a-4976-8cd1-08d207b831d3/

- ↑ Appel, Jacob M. (August 22, 2009). "Anticipating the Incapacitated Justice". Huffington Post. USA. Retrieved August 23, 2009.

- ↑ Ford, Gerald R. - A Time to Heal: The Autobiography of Gerald R. Ford, Harper & Row, 1979, p. 334. ISBN 0-06-011297-2.

- ↑ Ford, Gerald R. - A Time to Heal, p. 206.

- ↑ Woodward, Robert and Armstrong, Scott. The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court (1979). ISBN 978-0-380-52183-8; ISBN 0-380-52183-0. ISBN 978-0-671-24110-0; ISBN 0-671-24110-9; ISBN 0-7432-7402-4; ISBN 978-0-7432-7402-9.

- ↑ Woodward & Armstrong, pp.480–88, 526.

- ↑ Damasio, Antonio. "Descartes' Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Human Brain." Penguin Books, 1994. pg. 68–69.

- ↑ "Supreme Court Justices William O. Douglas (1898-1980)". michaelariens.com. Retrieved Aug 8, 2015.

- ↑ William O. Douglas Heritage Trail, Pacific Coast Trail (including map showing where incident occurred),

- ↑

- ↑ Woodward, Bob; Armstrong, Scott (1979). The Brethren. Simon & Schuster. p. 367.

- ↑ ; Niagara Falls Gazette, p. 12 (July 21, 1950).

- ↑ Archived March 23, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Newspaper Article - 'The marrying Justice'". Newspapers.nl.sg. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- ↑ Cloak and Gavel: FBI Wiretaps, Bugs, Informers, and the Supreme Court - Alexander Charns. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- 1 2 "The Supreme Court: September Song". Time.com. 1966-07-29. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- ↑ "Arlington National Cemetery - Home". Arlingtoncemetery.org. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- ↑ See This American Life, Transcript.

- ↑ "Christensen, George A. (1983) Here Lies the Supreme Court: Gravesites of the Justices, Yearbook". Archived from the original on September 3, 2005. Retrieved 2013-11-24. Supreme Court Historical Society

- ↑ Christensen, George A., Here Lies the Supreme Court: Revisited, Journal of Supreme Court History, Volume 33 Issue 1, Pages 17 – 41 (Feb 19, 2008), University of Alabama

- ↑ Charles Lane, On Further Review, It's Hard to Bury Douglas's Arlington Claim, Washington Post (Feb. 14, 2003).

- ↑ Charles Lane, On Further Review.

- 1 2 Archived May 11, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "60 Years Ago, Hike by Justice Douglas Saved the C&O Canal". Georgetowner.com. 2014-03-20. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- ↑ "Associate Justice William O. Douglas - Chesapeake & Ohio Canal National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". Nps.gov. Retrieved 2015-06-21.

- ↑ "Mountain—The Journey of Justice Douglas - Home". Dramatists Play Service. Retrieved 2015-06-22.

- ↑ Archived December 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

Further reading

- Abraham, Henry J., Justices and Presidents: A Political History of Appointments to the Supreme Court. 3d. ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1992). ISBN 0-19-506557-3.

- Cushman, Clare, The Supreme Court Justices: Illustrated Biographies,1789–1995 (2nd ed.) (Supreme Court Historical Society), (Congressional Quarterly Books, 2001) ISBN 1-56802-126-7; ISBN 978-1-56802-126-3.

- Frank, John P., The Justices of the United States Supreme Court: Their Lives and Major Opinions (Leon Friedman and Fred L. Israel, editors) (Chelsea House Publishers: 1995) ISBN 0-7910-1377-4, ISBN 978-0-7910-1377-9.

- Hall, Kermit L., ed. The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1992. ISBN 0-19-505835-6; ISBN 978-0-19-505835-2.

- Martin, Fenton S. and Goehlert, Robert U., The U.S. Supreme Court: A Bibliography, (Congressional Quarterly Books, 1990). ISBN 0-87187-554-3.

- Murphy, Bruce Allen, Wild Bill: The Legend and Life of William O. Douglas, (New York: Random House, 2003), ISBN 0-394-57628-4

- Pritchett, C. Herman, Civil Liberties and the Vinson Court. (The University of Chicago Press, 1969) ISBN 978-0-226-68443-7; ISBN 0-226-68443-1.

- "Adam M. Sowards". The Oregon Encyclopedia.

- Urofsky, Melvin I., Conflict Among the Brethren: Felix Frankfurter, William O. Douglas and the Clash of Personalities and Philosophies on the United States Supreme Court, Duke Law Journal (1988): 71–113.

- Urofsky, Melvin I., Division and Discord: The Supreme Court under Stone and Vinson, 1941–1953 (University of South Carolina Press, 1997) ISBN 1-57003-120-7.

- Urofsky, Melvin I., The Supreme Court Justices: A Biographical Dictionary (New York: Garland Publishing 1994). 590 pp. ISBN 0-8153-1176-1; ISBN 978-0-8153-1176-8.

- Woodward, Robert and Armstrong, Scott. The Brethren: Inside the Supreme Court (1979). ISBN 978-0-380-52183-8; ISBN 0-380-52183-0. ISBN 978-0-671-24110-0; ISBN 0-671-24110-9; ISBN 0-7432-7402-4; ISBN 978-0-7432-7402-9.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: William O. Douglas |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: William O. Douglas |

- William O. Douglas Papers at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library, Princeton University

- William O. Douglas at Find a Grave

- Oyez project, U.S. Supreme Court media on William O. Douglas.

- Points of Rebellion, by William O. Douglas

- Supreme Court Historical Society, William O. Douglas.

- William O. Douglas at the Biographical Directory of Federal Judges, a public domain publication of the Federal Judicial Center.

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by James Landis |

Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission 1937–1939 |

Succeeded by Jerome Frank |

| Legal offices | ||

| Preceded by Louis Brandeis |

Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States 1939–1975 |

Succeeded by John Paul Stevens |

| | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||