Zimmermann Telegram

The Zimmermann Telegram (or Zimmermann Note) was an internal diplomatic communication issued from the German Foreign Office in January 1917 that proposed a military alliance between Germany and Mexico in the event of the United States' entering World War I against Germany. The proposal was intercepted and decoded by British intelligence. Revelation of the contents enraged American public opinion, especially after the German Foreign Secretary Arthur Zimmermann publicly admitted the telegram was genuine on 3 March, and helped generate support for the United States declaration of war on Germany in April.[1]

Content

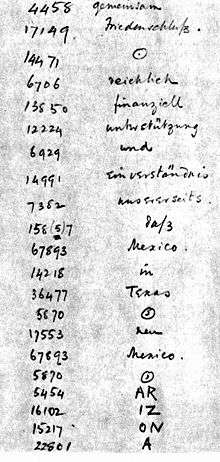

The message came in the form of a coded telegram dispatched by the Foreign Secretary of the German Empire, Arthur Zimmermann, on 11 January 1917. The message was sent to the German ambassador to Mexico, Heinrich von Eckardt. Zimmermann sent the telegram in anticipation of the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare by Germany on 1 February, an act the German government presumed would almost certainly lead to war with the United States. The telegram instructed Ambassador Eckardt that if the United States appeared certain to enter the war, he was to approach the Mexican Government with a proposal for military alliance with funding from Germany.

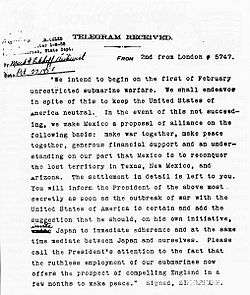

The decoded telegram is as follows:

- "We intend to begin on the first of February unrestricted submarine warfare. We shall endeavor in spite of this to keep the United States of America neutral. In the event of this not succeeding, we make Mexico a proposal of alliance on the following basis: make war together, make peace together, generous financial support and an understanding on our part that Mexico is to reconquer the lost territory in Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. The settlement in detail is left to you. You will inform the President of the above most secretly as soon as the outbreak of war with the United States of America is certain and add the suggestion that he should, on his own initiative, invite Japan to immediate adherence and at the same time mediate between Japan and ourselves. Please call the President's attention to the fact that the ruthless employment of our submarines now offers the prospect of compelling England in a few months to make peace." Signed, ZIMMERMANN

Mexican response

The Zimmermann Telegram was part of an effort carried out by the Germans to postpone the transportation of supplies and other war materials from the United States to the Allies of World War I that were at war with Germany.[2] The main purpose of the telegram was to make the Mexican government declare war on the United States in hopes of tying down American forces and slowing the export of American arms.[3] The German High Command believed they would be able to defeat the British and French on the Western Front and strangle Britain with unrestricted submarine warfare before American forces could be trained and shipped to Europe in sufficient numbers to aid the Allies. The Germans were encouraged by their successes on the Eastern Front into believing that they would be able to divert large numbers of troops to the Western Front in support of their goals.

Mexican President Venustiano Carranza assigned a military commission to assess the feasibility of the Mexican takeover of their former territories contemplated by Germany.[4] The general concluded that it would be neither possible nor even desirable to attempt such an enterprise for the following reasons:

- The United States was far stronger militarily than Mexico was. No serious scenarios existed under which Mexico could win a war against the United States.

- Germany's promises of "generous financial support" were very unreliable. The German government had already informed Carranza in June 1916 that they were unable to provide the necessary gold needed to stock a completely independent Mexican national bank.[5] Even if Mexico received financial support, the arms, ammunition, and other needed war supplies would presumably have to be purchased from the ABC nations (Argentina, Brazil, and Chile), which would strain relations with them, as explained below.

- Even if by some chance Mexico had the military means to win a conflict against the United States and reclaim the territories in question, Mexico would have severe difficulty accommodating a large English-speaking population that was better supplied with arms than most populations.

- Other foreign relations were at stake. The ABC nations organized the Niagara Falls peace conference in 1914 to avoid a full-scale war between the United States and Mexico over the United States occupation of Veracruz. If Mexico were to enter war against the United States, it would strain relations with those nations.

The Carranza government was recognized de jure by the United States on 31 August 1917 as a direct consequence of the Zimmermann telegram, since recognition was necessary to ensure Mexican neutrality in World War I.[6][7] After the military invasion of Veracruz in 1914, Mexico would not participate in any military excursions with the United States in World War I,[8] thus ensuring Mexican neutrality was the best outcome that the United States could hope for, even if Mexican neutrality would allow German companies to keep their operations in Mexico open.[9]

British interception

The telegram was sent to the German embassy in the United States for re-transmission to Eckardt in Mexico. It has traditionally been claimed that the telegram was sent over three routes: transmitted by radio and also sent over two trans-Atlantic telegraph cables operated by neutral governments (the United States and Sweden) for the use of their diplomatic services. But it has been established that only one method was used. The message was delivered to the United States Embassy in Berlin and then transmitted by diplomatic cable first to Copenhagen and then to London for onward transmission over transatlantic cable to Washington.[10] The misinformation about the "three routes" was spread by William Reginald Hall, then the head of Room 40, to try to conceal from the United States the fact that Room 40 was intercepting its cable traffic.

Direct telegraph transmission of the telegram was not possible because the British had cut the German international cables at the outbreak of war. However, the United States allowed limited use of its diplomatic cables for Germany to communicate with its ambassador in Washington. The facility was supposed to be used for cables connected with President Woodrow Wilson's peace proposals.[10]

The Swedish cable ran from Sweden, and the United States cable from the United States embassy in Denmark. However, neither cable ran directly to the United States. Both cables passed through a relay station at Porthcurno, near Land's End, the westernmost tip of England. Here the signals were boosted for the long trans-oceanic jump. All traffic through the Porthcurno relay was copied to British intelligence, in particular to the codebreakers and analysts in Room 40 at the Admiralty.[11] After their telegraph cables had been cut, the German Foreign Office appealed to the United States for use of their cable for diplomatic messages. President Wilson agreed to this, in the belief that such cooperation would sustain continued good relations with Germany, and that more efficient German-American diplomacy could assist Wilson's goal of a negotiated end to the war. The Germans handed in messages to the United States embassy in Berlin, which were relayed to the embassy in Denmark and then to the United States by American telegraph operators. However, the United States placed conditions on German usage, most notably that all messages had to be in the clear (i.e., uncoded). The Germans assumed that the United States cable was secure and used it extensively.[11]

Obviously, Zimmermann's note could not be given to the United States in the clear. The Germans therefore persuaded Ambassador James W. Gerard to accept it in coded form, and it was transmitted on 16 January 1917.[11]

In Room 40, Nigel de Grey had partially deciphered the telegram by the next day.[10] Room 40 had previously obtained German cipher documents, including the diplomatic cipher 13040 (captured in the Mesopotamian campaign), and naval cipher 0075, retrieved from the wrecked cruiser SMS Magdeburg by the Russians, who passed it to the British.[12]

Disclosure of the Telegram would obviously sway public opinion in the United States against Germany, provided the Americans could be convinced it was genuine. But Room 40 chief William Reginald Hall was reluctant to let it out, because the disclosure would expose the German codes broken in Room 40 and British eavesdropping on the United States cable. Hall waited three weeks. During this period, Grey and cryptographer William Montgomery completed the decryption. On 1 February Germany announced resumption of "unrestricted" submarine warfare, an act which led the United States to break off diplomatic relations with Germany on 3 February.[11]

Hall passed the telegram to the Foreign Office on 5 February, but still warned against releasing it. Meanwhile, the British discussed possible cover stories: to explain to the Americans how they got the ciphertext of the telegram without admitting to the cable snooping; and to explain how they got the cleartext of the telegram without letting the Germans know their codes were broken. Furthermore, the British needed to find a way to convince the Americans the message was not a forgery.

For the first story, the British obtained the ciphertext of the telegram from the Mexican commercial telegraph office. The British knew that the German Embassy in Washington would relay the message by commercial telegraph, so the Mexican telegraph office would have the ciphertext. "Mr. H", a British agent in Mexico, bribed an employee of the commercial telegraph company for a copy of the message. (Sir Thomas Hohler, then British ambassador in Mexico, claimed to have been "Mr. H", or at least involved with the interception, in his autobiography.) This ciphertext could be shown to the Americans without embarrassment. Moreover, the retransmission was enciphered using the older cipher 13040, so by mid-February the British had not only the complete text, but also the ability to release the telegram without revealing the extent to which the latest German codes had been broken—at worst, the Germans might have realized that the 13040 code had been compromised, but weighed against the possibility of United States entry into the war, that was a risk worth taking. Finally, since copies of the 13040 ciphertext would also have been deposited in the records of the American commercial telegraph, the British had the ability to prove the authenticity of the message to the United States government.

As a cover story, the British could publicly claim that their agents had stolen the telegram's deciphered text in Mexico. Privately, the British needed to give the Americans the 13040 cipher so that the United States government could verify the authenticity of the message independently with their own commercial telegraphic records; however the Americans agreed to back the official cover story. The German Foreign Office refused to consider a possible code break, and instead sent Eckardt on a witch-hunt for a traitor in the embassy in Mexico. (Eckardt indignantly rejected these accusations, and the Foreign Office eventually declared the embassy exonerated.)[11]

British use of the Telegram

On 19 February, Hall showed the Telegram to Edward Bell, secretary of the United States Embassy in Britain. Bell was at first incredulous, thinking it was a forgery. Once Bell was convinced the message was genuine, he became enraged. On 20 February Hall informally sent a copy to United States ambassador Walter Hines Page. On 23 February, Page met with British Foreign Minister Arthur Balfour and was given the ciphertext, the message in German, and the English translation. Then Page reported the story to President Wilson, including details to be verified from telegraph company files in the United States. Wilson released the text to the media on 28 February 1917.

Effect in the United States

Popular sentiment in the United States at that time was anti-Mexican as well as anti-German, while in Mexico there was considerable anti-American sentiment.[13] General John J. Pershing had long been chasing the revolutionary Pancho Villa and carried out several cross-border raids. News of the telegram further inflamed tensions between the United States and Mexico.

On the other hand, there was also a notable anti-British sentiment in the United States, particularly among German- and Irish-Americans. Many Americans wished to avoid the conflict in Europe. Since the public had been told (untruthfully) that the telegram had been stolen in a deciphered form in Mexico, the message was widely believed at first to be an elaborate forgery perpetrated by British intelligence. This belief, which was not restricted to pacifist and pro-German lobbies, was promoted by German and Mexican diplomats and by some American newspapers, especially the Hearst press empire. This presented the Wilson administration with a dilemma—with the evidence the United States had been provided confidentially by the British, Wilson realized the message was genuine—but he could not make the evidence public without compromising the British codebreaking operation.

However, any doubts as to the authenticity of the telegram were removed by Arthur Zimmermann himself. First at a press conference on 3 March 1917, he told an American journalist, "I cannot deny it. It is true." Then, on 29 March 1917, Zimmermann gave a speech in the Reichstag in which he admitted the telegram was genuine.[14] Zimmermann hoped Americans would understand the idea was that Germany would only fund Mexico's war with the United States in the event of American entry into World War I.

On 1 February 1917, Germany began unrestricted submarine warfare against all ships in the Atlantic bearing the American flag, both passenger and merchant ships. Two ships were sunk in February, and most American shipping companies held their ships in port. Besides the highly provocative war proposal to Mexico, the telegram also mentioned "ruthless employment of our submarines." Public opinion demanded action. Wilson had previously refused to assign US Navy crews and guns to the merchant ships. However, once the Zimmermann note was public, Wilson called for arming the merchant ships, but antiwar elements in the United States Senate blocked his proposal.[15]

Previous German efforts to promote war

Germany had long sought to incite a war between Mexico and the U.S., which would have tied down American forces and slowed the export of American arms to the Allies.[16] The Germans had engaged in a pattern of actively arming, funding and advising the Mexicans, as shown by the 1914 Ypiranga Incident[17] and the presence of German advisors during the 1918 Battle of Ambos Nogales. The German Naval Intelligence officer Franz von Rintelen had attempted to incite a war between Mexico and the United States in 1915, giving Victoriano Huerta $12 million for that purpose.[18] The German saboteur Lothar Witzke — responsible for the March 1917 munitions explosion at the Mare Island Naval Shipyard in the Bay Area,[19] and possibly responsible for the July 1916 Black Tom explosion in New Jersey — was based in Mexico City. The failure of United States troops to capture Pancho Villa in 1916 and the movement of President Carranza in favor of Germany emboldened the Germans to send the Zimmermann note.[20]

The German provocations were partially successful. Woodrow Wilson ordered the military invasion of Veracruz in 1914 in the context of the Ypiranga Incident and against the advice of the British government.[21] War was prevented thanks to the Niagara Falls peace conference organized by the ABC nations, but the occupation was a decisive factor in Mexican neutrality in World War I.[8] Mexico refused to participate in the embargo against Germany and granted full guarantees to the German companies for keeping their operations open, specifically in Mexico City.[9] These guarantees lasted for 25 years —coincidentally, it was on 22 May 1942 that Mexico declared war on the Axis Powers following the loss of two Mexican-flagged tankers that month to Kriegsmarine U-boats. Woodrow Wilson considered another military invasion of Veracruz and Tampico in 1917–1918,[22][23] so as to take control of the Tehuantepec Isthmus and Tampico oil fields,[23][24] but this time the relatively new Mexican President Venustiano Carranza threatened to destroy the oil fields in case the Marines landed there.[25][26]

In October 2005, the original British typescript of the deciphered Zimmermann Telegram was found.[27]

See also

- American entry into World War I

- Imperial German plans for the invasion of the United States

- Mexico in World War I

References

Notes

- ↑ Andrew, p. 42.

- ↑ Tuchman, pp. 63, 73–4

- ↑ Katz, pp. 328–29.

- ↑ Katz, p. 364

- ↑ William Beezley, Michael Meyer (2010) The Oxford History of Mexico, p. 476, Oxford University Press, UK.

- ↑ Thomas Paterson, J. Garry Clifford, Robert Brigham, Michael Donoghue, Kenneth Hagan (2010) American Foreign Relations, Volume 1: To 1920, p. 265, Cengage Learning, USA.

- ↑ Thomas Paterson, John Garry Clifford, Kenneth J. Hagan (1999) American Foreign Relations: A History since 1895, p. 51, Houghton Mifflin College Division, USA.

- 1 2 Lee Stacy (2002) Mexico and the United States, Volume 3, p. 869, Marshall Cavendish, USA.

- 1 2 Jürgen Buchenau (2004) Tools of Progress: A German Merchant Family in Mexico City, 1865–present, p. 82, UNM Press, USA.

- 1 2 3 Gannon

- 1 2 3 4 5 West, pp. 83, 87–92.

- ↑ Polmar & Noot

- ↑ Link

- ↑ Meyer, p. 76.

- ↑ Richard W Leopold, The Growth of American Foreign Policy: A History (1962) pp 330–31

- ↑ Katz, pp. 328–29.

- ↑ Katz, pp. 232–40.

- ↑ Katz, pp. 329–32.

- ↑ Tucker & Roberts, p. 1606

- ↑ Katz, pp. 346–47.

- ↑ Michael Small (2009) The Forgotten Peace: Mediation at Niagara Falls, 1914, p. 35, University of Ottawa, Canada.

- ↑ Ernest Gruening (1968) Mexico and Its Heritage, p. 596, Greenwood Press, U.S.

- 1 2 Drew Philip Halevy (2000) Threats of Intervention: U. S.-Mexican Relations, 1917–1923, p. 41, iUniverse, U.S.

- ↑ Lorenzo Meyer (1977) Mexico and the United States in the oil controversy, 1917–1942, p. 45, University of Texas Press, U.S.

- ↑ Stephen Haber, Noel Maurer, Armando Razo (2003) The Politics of Property Rights: Political Instability, Credible Commitments, and Economic Growth in Mexico, 1876–1929, p. 201, Cambridge University Press, UK.

- ↑ Lorenzo Meyer (1977) Mexico and the United States in the Oil Controversy, 1917–1942, p. 44, University of Texas Press, U.S.

- ↑ Fenton.

Bibliography

- Andrew, Christopher (1996). For The President's Eyes Only. Harper Collins. ISBN 0-00-638071-9.

- Beesly, Patrick (1982). Room 40: British Naval Intelligence, 1914–1918. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich. ISBN 0-15-178634-8.

- Boghardt, Thomas. The Zimmermann Telegram: Intelligence, Diplomacy, and America's Entry into World War I (2012) excerpt and text search; 319pp

- Boghardt, Thomas (November 2003). The Zimmermann Telegram: Diplomacy, Intelligence and The American Entry into World War I (PDF). Working Paper Series. Washington DC: The BMW Center for German and European Studies Edmund A. Walsh School of Foreign Service, Georgetown University. 6-04. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 2, 2006.; 35pp

- Fenton, Ben (17 October 2005). "Telegram that brought US into Great War is Found Found". The Telegraph. London.

- Gannon, Paul (2011). Inside Room 40: The Codebreakers of World War I. London: Ian Allen Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7110-3408-2.

- Hopkirk, Peter (1994). On Secret Service East of Constantinople. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280230-5.

- Katz, Friedrich (1981). The Secret War in Mexico: Europe, the United States, and the Mexican Revolution.

- Link, Arthur S. (1965). Wilson: Campaigns for Progressivism and Peace: 1916–1917.

- Massie, Robert K. (2007). Castles of Steel. London: Vantage Books. ISBN 978-0-09-952378-9.

- Meyer, Michael C. (1966). "The Mexican-German Conspiracy of 1915". The Americas. 23 (1): 76. doi:10.2307/980141.

- Polmar, Norman & Noot, Jurrien (1991). Submarines of the Russian and Soviet Navies 1718–1990. Annapolis: US Naval Institute Press.

- Pommerin, Reiner (1996). "Reichstagsrede Zimmermanns (Auszug), 30. März 1917". 'Quellen zu den deutsch-amerikanischen Beziehungen. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft Vol. 1. pp. 213–16.

- Singh, Simon (8 September 1999). "The Zimmermann Telegraph". The Independent. Independent Print Limited. Archived from the original on 1999. Retrieved 14 August 2014.

- Tuchman, Barbara W. (1958). The Zimmermann Telegram. ISBN 0-345-32425-0.

- Tucker, Spencer & Roberts, Priscilla Mary (2005). World War One. Santa Barbara CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1-85109-420-2.

- West, Nigel (1990). The Sigint Secrets: The Signals Intelligence War, 1990 to Today-Including the Persecution of Gordon Welchman. New York: Quill. ISBN 0-688-09515-1.

Further reading

- Bernstorff, Count Johann Heinrich (1920). My Three Years in America. New York: Scribner. pp. 310–11.

- Bridges, Lamar W. "Zimmermann telegram: reaction of Southern, Southwestern newspapers." Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly (1969) 46#1: 81–86.

- Dugdale, Blanche (1937). Arthur James Balfour. New York: Putnam. Vol. II, pp. 127–129.

- Hendrick, Burton J. (2003) [1925]. The Life and Letters of Walter H. Page. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 0-7661-7106-X.

- Kahn, David (1996) [1967]. The Codebreakers. New York: Macmillan.

- Winkler, Jonathan Reed (2008). Nexus: Strategic Communications and American Security in World War I. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02839-5.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zimmermann Telegram. |

- Failed Diplomacy: the Zimmermann Telegram

- The life and death of Charles Jastrow Mendelsohn and the breaking of the code.

- Our Documents – Zimmermann Telegram (1917)

- GermanNavalWarfare.info, Some Original Documents from the British Admiralty, Room 40, regarding the Zimmermann-/Mexico Telegram: Photocopies from The National Archives, Kew, Richmond, UK.

- Moving out of German Embassy after breaking relations, 1917

- Zimmermann Telegram: The Original Document, accessed 21 Feb 2015