Agrobacterium

| Agrobacterium | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Bacteria |

| Phylum: | Proteobacteria |

| Class: | Alpha Proteobacteria |

| Order: | Rhizobiales |

| Family: | Rhizobiaceae |

| Genus: | Agrobacterium |

| Type species | |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens (Smith and Townsend 1907) Conn 1942 | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Agrobacterium is a genus of Gram-negative bacteria established by H. J. Conn that uses horizontal gene transfer to cause tumors in plants. Agrobacterium tumefaciens is the most commonly studied species in this genus. Agrobacterium is well known for its ability to transfer DNA between itself and plants, and for this reason it has become an important tool for genetic engineering.

The Agrobacterium genus is quite heterogeneous. Recent taxonomic studies have reclassified all of the Agrobacterium species into new genera, such as Ahrensia, Pseudorhodobacter, Ruegeria, and Stappia,[1][2] but most species have been controversially reclassified as Rhizobium species.[3][4][5]

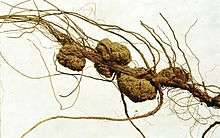

Plant pathogen

A. tumefaciens causes crown-gall disease in plants. The disease is characterised by a tumour-like growth or gall on the infected plant, often at the junction between the root and the shoot. Tumors are incited by the conjugative transfer of a DNA segment (T-DNA) from the bacterial tumour-inducing (Ti) plasmid. The closely related species, A. rhizogenes, induces root tumors, and carries the distinct Ri (root-inducing) plasmid. Although the taxonomy of Agrobacterium is currently under revision it can be generalised that 3 biovars exist within the genus, A. tumefaciens, A. rhizogenes, and A. vitis. Strains within A. tumefaciens and A. rhizogenes are known to be able to harbour either a Ti or Ri-plasmid, whilst strains of A. vitis, generally restricted to grapevines, can harbour a Ti-plasmid. Non-Agrobacterium strains have been isolated from environmental samples which harbour a Ri-plasmid whilst laboratory studies have shown that non-Agrobacterium strains can also harbour a Ti-plasmid. Some environmental strains of Agrobacterium possess neither a Ti nor Ri-plasmid. These strains are avirulent.[6]

The plasmid T-DNA is integrated semi-randomly into the genome of the host cell,[7] and the tumor morphology genes on the T-DNA are expressed, causing the formation of a gall. The T-DNA carries genes for the biosynthetic enzymes for the production of unusual amino acids, typically octopine or nopaline. It also carries genes for the biosynthesis of the plant hormones, auxin and cytokinins, and for the biosynthesis of opines, providing a carbon and nitrogen source for the bacteria that most other micro-organisms can't use, giving Agrobacterium a selective advantage.[8] By altering the hormone balance in the plant cell, the division of those cells cannot be controlled by the plant, and tumors form. The ratio of auxin to cytokinin produced by the tumor genes determines the morphology of the tumor (root-like, disorganized or shoot-like).

In humans

Although generally seen as an infection in plants, Agrobacterium can be responsible for opportunistic infections in humans with weakened immune systems,[9][10] but has not been shown to be a primary pathogen in otherwise healthy individuals. One of the earliest associations of human disease caused by Agrobacterium radiobacter was reported by Dr. J. R. Cain in Scotland (1988).[11] A later study suggested that Agrobacterium attaches to and genetically transforms several types of human cells by integrating its T-DNA into the human cell genome. The study was conducted using cultured human tissue and did not draw any conclusions regarding related biological activity in nature.[12]

Uses in biotechnology

The ability of Agrobacterium to transfer genes to plants and fungi is used in biotechnology, in particular, genetic engineering for plant improvement. A modified Ti or Ri plasmid can be used. The plasmid is 'disarmed' by deletion of the tumor inducing genes; the only essential parts of the T-DNA are its two small (25 base pair) border repeats, at least one of which is needed for plant transformation.[13][14] The genes to be introduced into the plant are cloned into a plant transformation vector that contains the T-DNA region of the disarmed plasmid, together with a selectable marker (such as antibiotic resistance) to enable selection for plants that have been successfully transformed. Plants are grown on media containing antibiotic following transformation, and those that do not have the T-DNA integrated into their genome will die. An alternative method is agroinfiltration.[15][16]

Transformation with Agrobacterium can be achieved in two ways. Protoplasts or alternatively leaf-discs can be incubated with the Agrobacterium and whole plants regenerated using plant tissue culture. A common transformation protocol for Arabidopsis is the floral-dip method:[17] inflorescence are dipped in a suspension of Agrobacterium, and the bacterium transforms the germline cells that make the female gametes. The seeds can then be screened for antibiotic resistance (or another marker of interest), and plants that have not integrated the plasmid DNA will die when exposed to the correct condition of antibiotic.[15]

Agrobacterium does not infect all plant species, but there are several other effective techniques for plant transformation including the gene gun.

Agrobacterium is listed as being the vector of genetic material that was transferred to these USA GMOs:[18]

- Soybean

- Cotton

- Corn

- Sugar Beet

- Alfalfa

- Wheat

- Rapeseed Oil (Canola)

- Creeping bentgrass (for animal feed)

- Rice (Golden Rice)

Genomics

The sequencing of the genomes of several species of Agrobacterium has permitted the study of the evolutionary history of these organisms and has provided information on the genes and systems involved in pathogenesis, biological control and symbiosis. One important finding is the possibility that chromosomes are evolving from plasmids in many of these bacteria. Another discovery is that the diverse chromosomal structures in this group appear to be capable of supporting both symbiotic and pathogenic lifestyles. The availability of the genome sequences of Agrobacterium species will continue to increase, resulting in substantial insights into the function and evolutionary history of this group of plant-associated microbes.[19]

History

Marc Van Montagu and Jozef Schell at the University of Ghent (Belgium) discovered the gene transfer mechanism between Agrobacterium and plants, which resulted in the development of methods to alter Agrobacterium into an efficient delivery system for gene engineering in plants.[13][14] A team of researchers led by Dr Mary-Dell Chilton were the first to demonstrate that the virulence genes could be removed without adversely affecting the ability of Agrobacterium to insert its own DNA into the plant genome (1983).

See also

- Agroinfiltration

- Marc Van Montagu

- Rhizobium rhizogenes (formerly Agrobacterium rhizogenes)

References

- ↑ Uchino, Yoshihito; Yokota, Akira; Sugiyama, Junta (1997). "Phylogenetic position of the marine subdivision of Agrobacterium species based on 16S rRNA sequence analysis". The Journal of General and Applied Microbiology. 43 (4): 243–247. doi:10.2323/jgam.43.243. PMID 12501326.

- ↑ Uchino, Yoshihito; Hirata, Aiko; Yokota, Akira; Sugiyama, Junta (1998). "Reclassification of marine Agrobacterium species: Proposals of Stappia stellulata gen. nov., comb. Nov., Stappia aggregata sp. nov., nom. Rev., Ruegeria atlantica gen. nov., comb. Nov., Ruegeria gelatinovora comb. Nov., Ruegeria algicola comb. Nov., and Ahrensia kieliense gen. nov., sp. nov., nom. Rev". The Journal of General and Applied Microbiology. 44 (3): 201–210. doi:10.2323/jgam.44.201. PMID 12501429.

- ↑ Young, J. M.; Kuykendall, L. D.; Martínez-Romero, E; Kerr, A; Sawada, H (2001). "A revision of Rhizobium Frank 1889, with an emended description of the genus, and the inclusion of all species of Agrobacterium Conn 1942 and Allorhizobium undicola de Lajudie et al. 1998 as new combinations: Rhizobium radiobacter, R. rhizogenes, R. rubi, R. undicola, and R. vitis". Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 51 (Pt 1): 89–103. doi:10.1099/00207713-51-1-89. PMID 11211278.

- ↑ Farrand, S. K.; Van Berkum, P. B.; Oger, P (2003). "Agrobacterium is a definable genus of the family Rhizobiaceae". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 53 (5): 1681–7. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.02445-0. PMID 13130068.

- ↑ Young, J. M.; Kuykendall, L. D.; Martínez-Romero, E; Kerr, A; Sawada, H (2003). "Classification and nomenclature of Agrobacterium and Rhizobium—a reply to Farrand et al. (2003)". International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 53 (5): 1689–95. doi:10.1099/ijs.0.02762-0. PMID 13130069.

- ↑ Sawada, H.; Ieki, H.; Oyaizu, H.; Matsumoto, S. (1993). "Proposal for Rejection of Agrobacterium tumefaciens and Revised Descriptions for the Genus Agrobacterium and for Agrobacterium radiobacter and Agrobacterium rhizogenes". International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology. 43 (4): 694. doi:10.1099/00207713-43-4-694. PMID 8240952.

- ↑ Francis, Kirk E.; Spiker, Steven (2004). "Identification of Arabidopsis thaliana transformants without selection reveals a high occurrence of silenced T-DNA integrations". The Plant Journal. 41 (3): 464–77. doi:10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02312.x. PMID 15659104.

- ↑ Pitzschke, Andrea; Hirt, Heribert (2010). "New insights into an old story: Agrobacterium-induced tumour formation in plants by plant transformation". The EMBO Journal. 29 (6): 1021–32. doi:10.1038/emboj.2010.8. PMC 2845280

. PMID 20150897.

. PMID 20150897. - ↑ Hulse, M.; Johnson, S.; Ferrieri, P. (1993). "Agrobacterium Infections in Humans: Experience at One Hospital and Review". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 16 (1): 112–7. doi:10.1093/clinids/16.1.112. PMID 8448285.

- ↑ Dunne Jr, W. M.; Tillman, J; Murray, J. C. (1993). "Recovery of a strain of Agrobacterium radiobacter with a mucoid phenotype from an immunocompromised child with bacteremia". Journal of clinical microbiology. 31 (9): 2541–3. PMC 265809

. PMID 8408587.

. PMID 8408587. - ↑ Cain, John Raymond (1988). "A case of septicaemia caused by Agrobacterium radiobacter". Journal of Infection. 16 (2): 205–6. doi:10.1016/s0163-4453(88)94272-7. PMID 3351321.

- ↑ Kunik, T.; Tzfira, T; Kapulnik, Y; Gafni, Y; Dingwall, C; Citovsky, V (2001). "Genetic transformation of HeLa cells by Agrobacterium". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 98 (4): 1871–6. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.1871K. doi:10.1073/pnas.041327598. JSTOR 3054968. PMC 29349

. PMID 11172043.

. PMID 11172043. - 1 2 Schell, J.; Van Montagu, M. (1977). "The Ti-Plasmid of Agrobacterium Tumefaciens, A Natural Vector for the Introduction of NIF Genes in Plants?". In Hollaender, Alexander; Burris, R. H.; Day, P. R.; Hardy, R. W. F.; Helinski, D. R.; Lamborg, M. R.; Owens, L.; Valentine, R. C. Genetic Engineering for Nitrogen Fixation. Basic Life Sciences. 9. pp. 159–79. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-0880-5_12. ISBN 978-1-4684-0882-9. PMID 336023.

- 1 2 Joos, H; Timmerman, B; Montagu, M. V.; Schell, J (1983). "Genetic analysis of transfer and stabilization of Agrobacterium DNA in plant cells". The EMBO Journal. 2 (12): 2151–60. PMC 555427

. PMID 16453483.

. PMID 16453483. - 1 2 Thomson JA. "Genetic Engineering of Plants" (PDF). Biotechnology. Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems. 3. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ↑ Leuzinger K, Dent M, Hurtado J, Stahnke J, Lai H, Zhou X, Chen Q (2013). "Efficient Agroinfiltration of Plants for High-level Transient Expression of Recombinant Proteins". Journal of Visualized Experiments. 77 (50521). PMC 3846102

.

. - ↑ Clough, Steven J.; Bent, Andrew F. (1998-12-01). "Floral dip: a simplified method forAgrobacterium-mediated transformation ofArabidopsis thaliana". The Plant Journal. 16 (6): 735–743. doi:10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. ISSN 1365-313X.

- ↑ The FDA List of Completed Consultations on Bioengineered Foods Archived May 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Setubal, Joao C.; WOod, Derek; Burr, Thomas; Farrand, Stephen K.; Goldman, Barry S.; Goodner, Brad; Otten, Leon; Slater, Steven (2009). "The Genomics of Agrobacterium: Insights into its Pathogenicity, Biocontrol, and Evolution". In Jackson, Robert W. Plant Pathogenic Bacteria: Genomics and Molecular Biology. Caister Academic Press. pp. 91–112. ISBN 978-1-904455-37-0.

External links

- Kyndt, Tina; Quispe, Dora; Zhai, Hong; Jarret, Robert; Ghislain, Marc; Liu, Qingchang; Gheysen, Godelieve; Kreuze, Jan F. (2015). "The genome of cultivated sweet potato contains Agrobacterium T-DNAs with expressed genes: An example of a naturally transgenic food crop". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112: 201419685. doi:10.1073/pnas.1419685112. Lay summary – Phys.org (April 21, 2015).

- Current taxonomy of Agrobacterium species, and new Rhizobium names

- Agrobacteria is used as gene ferry - Plant transformation with Agrobacterium]