Kambojas

The Kambojas were a tribe of Iron Age India, frequently mentioned in Sanskrit and Pali literature.

Ethnicity and language

The ancient Kambojas were probably of Indo-Iranian origin.[1] They are, however, sometimes described as Indo-Aryans[2][3][4] and sometimes as having both Indian and Iranian affinities.[5][6][7] The Kambojas are also described as a royal clan of the Sakas.[8]

Origins

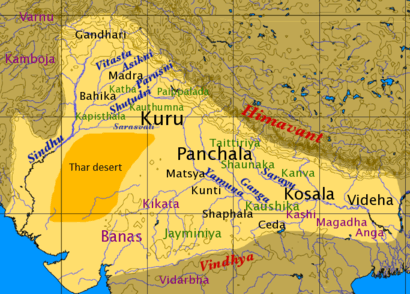

The earliest reference to the Kambojas is in the works of Pāṇini, around the 5th century BCE. Other pre-Common Era references appear in the Manusmriti (2nd century) and the Mahabharata (1st century), both of which described the Kambojas as former kshatriyas who had degraded through a failure to abide by Hindu sacred rituals.[9] Their territories were located beyond Gandhara, beyond Pakistan, Afghanistan laying in Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan where Buddha statues were built in the name of king Maurya & Ashoka[10] and the 3rd century BCE Edicts of Ashoka refers to the area under Kamboja control as being independent of the Mauryan empire in which it was situated.[9]

Some sections of the Kambojas crossed the Hindu Kush and planted Kamboja colonies in Paropamisadae and as far as Rajauri. The Mahabharata locates the Kambojas on the near side of the Hindu Kush as neighbors to the Daradas, and the Parama-Kambojas across the Hindu Kush as neighbors to the Rishikas (or Tukharas) of the Ferghana region.[11][12][13]

The confederation of the Kambojas may have stretched from the valley of Rajauri in the south-western part of Kashmir to the Hindu Kush Range; in the south–west the borders extended probably as far as the regions of Kabul, Ghazni and Kandahar, with the nucleus in the area north-east of the present day Kabul, between the Hindu Kush Range and the Kunar river, including Kapisa[14][15] possibly extending from the Kabul valleys to Kandahar.[16]

Others locate the Kambojas and the Parama-Kambojas in the areas spanning Balkh, Badakshan, the Pamirs and Kafiristan.[17] D. C. Sircar supposed them to have lived "in various settlements in the wide area lying between Punjab, Iran, to the south of Balkh."[18] and the Parama-Kamboja even farther north, in the Trans-Pamirian territories comprising the Zeravshan valley, towards the Farghana region, in the Scythia of the classical writers.[2][19][20] The mountainous region between the Oxus and Jaxartes is also suggested as the location of the ancient Kambojas.[21]

The name Kamboja may derive from (Kam + bhuj), referring to the people of a country known as "Kum" or "Kam". The mountainous highlands where the Jaxartes and its confluents arise are called the highlands of the Komedes by Ptolemy. Ammianus Marcellinus also names these mountains as Komedas.[22][23][24] The Kiu-mi-to in the writings of Xuanzang have also been identified with the Komudha-dvipa of the Puranic literature and the Iranian Kambojas.[25][26]

The two Kamboja settlements on either side of the Hindu Kush are also substantiated from Ptolemy's Geography, which refers to the Tambyzoi located north of the Hindu Kush on the river Oxus in Bactria, and the Ambautai people on the southern side of Hindukush in the Paropamisadae. Scholars have identified both the Ptolemian Tambyzoi and Ambautai with Sanskrit Kamboja.[11][27][28][29][30]

Theory of Origin - Eurasian Nomads

Some scholars believe that the Trans-Caucasian hydronyms and toponyms viz. Cyrus, Cambyses and Cambysene were due to tribal extension of the Iranian ethnics — the Kurus and Kambojas of the Indian texts, who according to them, had moved to the north of the Medes in Armenian Districts in remote antiquity.[31]

Kambojan States

The capital of Kamboja was probably Rajapura (modern Rajauri). The Kamboja Mahajanapada of Buddhist traditions refers to this branch.[32]

Kautiliya's Arthashastra and Ashoka's Edict No. XIII attest that the Kambojas followed a republican constitution. Pāṇini's Sutras tend to convey that the Kamboja of Pāṇini was a "Kshatriya monarchy", but "the special rule and the exceptional form of derivative" he gives to denote the ruler of the Kambojas implies that the king of Kamboja was a titular head (king consul) only.[33] One king of Kamboja was King Srindra Varmana Kamboj.[34]

The Aśvakas

The Kambojas were famous in ancient times for their excellent breed of horses and as remarkable horsemen located in the Uttarapatha or north-west.[35][36] They were constituted into military sanghas and corporations to manage their political and military affairs. The Kamboja cavalry offered their military services to other nations as well. There are numerous references to Kamboja having been requisitioned as cavalry troopers in ancient wars by outside nations.[37][38]

It was on account of their supreme position in horse (Ashva) culture that the ancient Kambojas were also popularly known as Ashvakas, i.e. horsemen. Their clans in the Kunar and Swat valleys have been referred to as Assakenoi and Aspasioi in classical writings, and Ashvakayanas and Ashvayanas in Pāṇini's Ashtadhyayi.

The Kambojas were famous for their horses and as cavalry-men (aśva-yuddha-Kuśalah), Aśvakas, 'horsemen', was the term popularly applied to them... The Aśvakas inhabited Eastern Afghanistan, and were included within the more general term Kambojas.— K.P.Jayswal[36]

Elsewhere Kamboja is regularly mentioned as "the country of horses" (Asvanam ayatanam), and it was perhaps this well-established reputation that won for the horsebreeders of Bajaur and Swat the designation Aspasioi (from the Old Pali aspa) and assakenoi (from the Sanskrit asva "horse").

Conflict with Alexander

The Kambojas entered into conflict with Alexander the Great as he invaded Central Asia. The Macedonian conqueror made short shrift of the arrangements of Darius and after over-running the Achaemenid Empire he dashed into Afghanistan. There he encountered incredible resistance of the Kamboja Aspasioi and Assakenoi tribes.[40][41]

The Ashvayans (Aspasioi) were also good cattle breeders and agriculturists. This is clear from the large number of bullocks, 230,000 according to Arrian, of a size and shape superior to what the Macedonians had known, that Alexander captured from them and decided to send to Macedonia for agriculture.[42][43]

Migrations

During the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE, clans of the Kambojas from north Afghanistan in alliance with the Sakas, Pahlavas and the Yavanas entered India, spread into Sindhu, Saurashtra, Malwa, Rajasthan, Punjab and Surasena, and set up independent principalities in western and south-western India. Later, a branch of the same people took Gauda and Varendra territories from the Palas and established the Kamboja-Pala Dynasty of Bengal in Eastern India.[44][45][46]

There are references to the hordes of the Sakas, Yavanas, Kambojas, and Pahlavas in the Bala Kanda of the Valmiki Ramayana. In these verses one may see glimpses of the struggles of the Hindus with the invading hordes from the north-west.[4][47][48] The royal family of the Kamuias mentioned in the Mathura Lion Capital are believed to be linked to the royal house of Taxila in Gandhara.[49] In the medieval era, the Kambojas are known to have seized north-west Bengal (Gauda and Radha) from the Palas of Bengal and established their own Kamboja-Pala Dynasty. Indian texts like Markandeya Purana, Vishnu Dharmottari Agni Purana,[50]

Eastern Kambojas

A branch of Kambojas seems to have migrated eastwards towards Nepal and Tibet in the wake of Kushana (1st century) or else Huna (5th century) pressure and hence their notice in the chronicles of Tibet ("Kam-po-tsa, Kam-po-ce, Kam-po-ji") and Nepal (Kambojadesa).[51][52][53] The 5th-century Brahma Purana mentions the Kambojas around Pragjyotisha and Tamraliptika.[54][55][56][57]

The Kambojas of ancient India are known to have been living in north-west, but in this period (9th century AD), they are known to have been living in the north-east India also, and very probably, it was meant Tibet.[58]

The last Kambojas ruler of the Kamboja-Pala Dynasty Dharmapala was defeated by the south Indian Emperor Rajendra Chola I of the Chola dynasty in the 11th century.[59][60]

Mauryan period

The Kambojas find prominent mention as a unit in the 3rd-century BCE Edicts of Ashoka. Rock Edict XIII tells us that the Kambojas had enjoyed autonomy under the Mauryas.[4][61] The republics mentioned in Rock Edict V are the Yonas, Kambojas, Gandharas, Nabhakas and the Nabhapamkitas. They are designated as araja. vishaya in Rock Edict XIII, which means that they were kingless, i.e. republican polities. In other words, the Kambojas formed a self-governing political unit under the Maurya emperors.[62][63]

Ashoka sent missionaries to the Kambojas to convert them to Buddhism, and recorded this fact in his Rock Edict V.[64][65]

See also

References

- ↑ Dwivedi 1977: 287 "The Kambojas were probably the descendants of the Indo-Iranians popularly known later on as the Sassanians and Parthians who occupied parts of north-western India in the first and second centuries of the Christian era."

- 1 2 Mishra 1987

- ↑ Ramesh Chandra Majumdar, Achut Dattatrya Pusalker, A. K. Majumdar, Dilip Kumar Ghose, Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan, Vishvanath Govind Dighe. The History and Culture of the Indian People, 1962, p 264,

- 1 2 3 "Political History of Ancient India", H. C. Raychaudhuri, B. N. Mukerjee, University of Calcutta, 1996.

- ↑ See: Vedic Index of names & subjects by Arthur Anthony Macdonnel, Arthur. B Keath, I.84, p 138.

- ↑ See more Refs: Ethnology of Ancient Bhārata, 1970, p 107, Ram Chandra Jain; The Journal of Asian Studies, 1956, p 384, Association for Asian Studies, Far Eastern Association (U.S.)

- ↑ India as Known to Pāṇini: A Study of the Cultural Material in the Ashṭādhyāyī, 1953, p 49, Vasudeva Sharana Agrawala; Afghanistan, p 58, W. K. Fraser, M. C. Gillet; Afghanistan, its People, its Society, its Culture, Donal N. Wilber, 1962, p 80, 311

- ↑ Walker and Tapp 2001

- 1 2 Encyclopedia of the Peoples of Asia and Oceania, Barbara A. West, Infobase Publishing (2009), ISBN 9781438119137 p. 359

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Indica, "The Kambojas: Land and its Identification", First Edition, 1998 New Delhi, page 528

- 1 2 Sethna, K. D. (2000) Problems of Ancient India, New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. ISBN 81-7742-026-7

- ↑ Numerous scholars now locate the Kamboja realm on the southern side of the Hindu Kush ranges (in the Kabul, Swat, and Kunar valleys) and the Parama-Kambojas in the territories on the north side of the Hindu Kush. See: Geographical and Economic Studies in the Mahābhārata: Upāyana Parva, 1945, p 11-13, Moti Chandra - India; Geographical Data in the Early Purāṇas: A Critical Study, 1972, p 165/66, M. R. Singh

- ↑ Purana, Vol VI, No 1, January 1964, p 207 sqq; Inscriptions of Asoka: Translation and Glossary, 1990, p 86, Beni Madhab Barua, Binayendra Nath Chaudhury - Inscriptions, Prakrit).

- ↑ The Peoples of Pakistan: An Ethnic History, 1971, pp 64-67, Yuri Vladimirovich Gankovski - Ethnology.

- ↑ History of the Pathans, 2002, p 11, Haroon Rashid - Pushtuns.

- ↑ Michael Witzel Persica-9, p 92, fn 81.

- ↑ Asoka and His Inscriptions, 1968, pp 93-96, Beni Madhab Barua, Ishwar Nath Topa.

- ↑ Sircar, D. C. (1971). Studies in the Geography of Ancient and Medieval India. p. 100.

- ↑ See: Proceedings and Transactions of the All-India Oriental Conference, 1930, p 118, J. C. Vidyalankara

- ↑ The Deeds of Harsha: Being a Cultural Study of Bāṇa's Harshacharita, 1969, p 199, Vasudeva Sharana Agrawala

- ↑ Central Asiatic Provinces of the Mauryan Empire, p 403, H. C. Seth; See also: Indian Historical Quarterly, Vol. XIII, 1937, No 3, p. 400; Journal of the Asiatic Society, 1940, p 37, (India) Asiatic Society (Calcutta, Royal Asiatic Society of Bengal - Asia; cf: History and Archaeology of India's Contacts with Other Countries, from Earliest Times to 300 B.C., 176, p 152, Shashi P. Asthana; Mahabharata Myth and Reality, 1976, p 232, Swarajya Prakash Gupta, K. S. Ramachandran. Cf also: India and Central Asia, p 25 etc, P. C. Bagchi.

- ↑ Indian Historical Quarterly, 1963, p 403; Central Asiatic provinces of the Maurya Empire, p403, H.C. Seth

- ↑ History and Archaeology of India's Contacts with Other Countries, from Earliest Times to 300 B.C., 1976, p 152, Shashi Asthana; Mahabharata Myth and Reality, 1976, p 232, Swarajya Prakash Gupta, K. S. Ramachandran.

- ↑ "The Town of Darwaz in Badakshan is still called Khum (Kum) or Kala-i-Khum. It stands for the valley of Basht. The name Khum or Kum conceals the relics of ancient Kamboja" (Journal of the Asiatic Society, 1956, p 256, Buddha Prakash [Asiatic Society (Calcutta, India), Asiatic Society of Bengal]).

- ↑ India and the World, p 71, Buddha Prakash; also see: Central Asiatic Provinces of Maurya Empire, p 403, H. C. Seth; India and Central Asia, p 25, P. C. Bagchi

- ↑ Journal of the Asiatic Society, 1956, p 256, Asiatic Society (Calcutta, India), Asiatic Society of Bengal.

- ↑ Talbert 2000, p. 99

- ↑ For Tambyzoi=Kamboja, see refs: Pre Aryan and Pre Dravidian in India, 1993, p 122, Sylvain Lévi, Jean Przyluski, Jules Bloch, Asian Educational Services; Cities and Civilization, 1962, p 172, Govind Sadashiv Ghurye

- ↑ For Ambautai=Kamboja, see Witzel 1999a

- ↑ Patton and Bryant 2005, p. 257

- ↑ Histoire Auguste: Pt. 2. Vies des deux Valérines et des deux Galliens, 2000, p 90, Ammn Marcellin, Jean Pierre Callu, O. Desbordes (Les hydronymes de Transcaucasie, en question ici, auraient pu, dès lors, aussi dériver aussi de ces ethniques, lors de l'extension des tribus iraniennes vers le Nord de la Médie, et non pas de ces souverains achéménides — dont la présente légende répond mieux à l'ingéniosité «heurématique» des Grecs)

- ↑ See: Problems of Ancient India, 2000, p 5-6; cf: Geographical Data in the Early Puranas, p 168.

- ↑ Hindu Polity: A Constitutional History of India in Hindu Times, Parts I and II., 1955, p 52, Dr Kashi Prasad Jayaswal - Constitutional history; Prācīna Kamboja, jana aura janapada =: Ancient Kamboja, people and country, 1981, Dr Jiyālāla Kāmboja - Kamboja (Pakistan).

- ↑ Studies in Skanda Purana, 1978, p 59, A. B. L. Awasthi.

- ↑ The Indian Historical Quarterly, 1963, p 103

- 1 2 Hindu Polity, 1978, pp 121, 140, K. P. Jayswal.

- ↑ War in Ancient India, 1944, p 178, V. R. Ramachandra Dikshitar - Military art and science.

- ↑ The Indian Historical Quarterly, 1963, p 103; The Achaemenids in India, 1950, p 47, Sudhakar Chattopadhyaya; Poona Orientalist: A Quarterly Journal Devoted to Oriental Studies, 1945, P i, (edi) Har Dutt Sharma; The Poona Orientalist, 1936, p 13, Sanskrit philology

- ↑ "Par ailleurs le Kamboja est régulièrement mentionné comme la "patrie des chevaux" (Asvanam ayatanam), et cette reputation bien etablie gagné peut-etre aux eleveurs de chevaux du Bajaur et du Swat l'appellation d'Aspasioi (du v.-p. aspa) et d'assakenoi (du skt asva "cheval")". E. Lamotte, Historie du Bouddhisme Indien, p. 110. (WP translation. Quotation should be taken from the published English translation: Lamotte 1988, p. 100)

- ↑ Panjab Past and Present, pp 9-10; also see: History of Porus, pp 12, 38, Buddha Parkash

- ↑ Proceedings, 1965, p 39, by Punjabi University. Dept. of Punjab Historical Studies - History.

- ↑ History of Punjab, 1997, Editors: Fauja Singh, L. M. Joshi

- ↑ Acharya 2001, p 91

- ↑ Geographical Data in the Early Purāṇas: A Critical Study, 1972, p 168, M. R. Singh - India.

- ↑ History of Ceylon, 1959, p 91, Ceylon University, University of Ceylon, Peradeniya, Hem Chandra Ray, K. M. De Silva.

- ↑ Pande (R.) 1984, p. 93

- ↑ Shrava 1981, p. 12

- ↑ Rishi, 1982, p. 100

- ↑ See: Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, Vol II, Part I, p xxxvi; see also p 36, Sten Konow; Indian Culture, 1934, p 193, Indian Research Institute; Cf: Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, 1990, p 142, Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland - Middle East.

- ↑ Indian Historical Quarterly, 1963, p 127

- ↑ Shastri and Choudhury 1982, p. 112

- ↑ B. C. Sen, Some Historical Aspects of the Inscriptions of Bengal, p. 342, fn 1

- ↑ Vaidya 1986, p. 221

- ↑ M. R. Singh, A Critical Study of the Geographical Data in the Early Puranas, p. 168

- ↑ Ganguly 1994, p. 72, fn 168

- ↑ H. C. Ray, The Dynastic History of Northern India, I, p. 309

- ↑ A. D. Pusalkar, R. C. Majumdar et al., History and Culture of Indian People, Imperial Kanauj, p. 323,

- ↑ R. R. Diwarkar (ed.), Bihar Through the Ages, 1958, p. 312

- ↑ Ancient Indian History and Civilization by Sailendra Nath Sen p.281

- ↑ The Cambridge Shorter History of India p.145

- ↑ H. C. Raychaudhury, B. N. Mukerjee; Asoka and His Inscriptions, 3d Ed, 1968, p 149, Beni Madhab Barua, Ishwar Nath Topa.

- ↑ Hindu Polity, A Constitutional History of India in Hindu Times, 1978, p 117-121, K. P. Jayswal; Ancient India, 2003, pp 839-40, V. D. Mahajan; Northern India, p 42, Mehta Vasisitha Dev Mohan etc

- ↑ Bimbisāra to Aśoka: With an Appendix on the Later Mauryas, 1977, p 123, Sudhakar Chattopadhyaya.

- ↑ The North-west India of the Second Century B.C., 1974, p 40, Mehta Vasishtha Dev Mohan - India; Tribes in Ancient India, 1973, p 7

- ↑ Yar-Shater 1983, p. 951

Bibliography

- Acharya, K. T. (2001) A Historical Dictionary of Indian Food (Oxford India Paperbacks). ISBN 978-0-19-565868-2

- Barnes, Ruth and David Parkin (eds.) (2002) Ships and the Development of Maritime Technology on the Indian Ocean. London: Curzon. ISBN 0-7007-1235-6

- Bhatia, Harbans Singh (1984) Political, legal, and military history of India. New Delhi: Deep & Deep Publications

- Bhattacharyya, Alakananda (2003) The Mlechchhas in Ancient India, Kolkata: Firma KLM. ISBN 81-7102-112-3

- Boardman, John and N. G. L. Hammond, D. M. Lewis, and M. Ostwald (1988) The Cambridge Ancient History: Volume 4, Persia, Greece and the Western Mediterranean (c. 525 to 479 BC). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-22804-2

- Bongard-Levin, Grigoriĭ Maksimovich (1985) Ancient Indian Civilization. New Delhi: Arnold-Heinemann

- Bowman, John Stewart (2000) Columbia chronologies of Asian history and culture, New York; Chichester: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-11004-9

- Boyce, Mary and Frantz Grenet (1991) A History of Zoroastrianism, Vol. 3, Zoroastrianism under Macedonian and Roman rule. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 90-04-09271-4

- Collins, Steven (1998) Nirvana and Other Buddhist Felicities: Utopias of the Pali Imaginaire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-57054-9. ISBN 0-521-57842-6 ISBN 978-0-521-57842-4

- Drabu, V. N. (1986) Kashmir Polity, c. 600-1200 A.D. New Delhi: Bahri Publications. Series in Indian history, art, and culture; 2. ISBN 81-7034-004-7

- Ganguly, Dilip Kumar (1994) Ancient India, History and Archaeology. New Delhi: Abhinav Publications. ISBN 81-7017-304-3

- Dwivedi, R. K., (1977) "A Critical study of Changing Social Order at Yuganta: or the end of the Kali Age" in Lallanji Gopal, J.P. Singh, N. Ahmad and D. Malik (eds.) (1977) D.D. Kosambi commemoration volume. Varanasi: Banaras Hindu University.

- Jha, Jata Shankar (ed.) (1981) K.P. Jayaswal commemoration volume. Patna: K P Jayaswal Research Institute

- Jindal, Mangal Sen (1992) History of Origin of Some Clans in India, with Special Reference to Jats. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons. ISBN 81-85431-08-6

- Lamotte, Etienne (1988) History of Indian Buddhism: From the Origins to the Saka Era. Sara Webb-Boin and Jean Dantinne (transl.) Louvain-la-Neuve: Université Catholique de Louvain, Institut Orientaliste. ISBN 90-6831-100-X

- Mishra, Krishna Chandra (1987) Tribes in the Mahabharata: A Socio-cultural Study. New Delhi, India: National Pub. House. ISBN 81-214-0028-7

- Misra, Satiya Deva (ed.) (1987) Modern Researches in Sanskrit: Dr. Veermani Pd. Upadhyaya Felicitation Volume. Patna: Indira Prakashan

- Pande, Govind Chandra (1984) Foundations of Indian Culture, Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass ISBN 81-208-0712-X (1990 edition.)

- Pande, Ram (ed.) (1984) Tribals Movement [proceedings of the National Seminar on Tribals of Rajasthan held on 9–10 April 1983 at Jaipur under the auspices of Shodhak in collaboration of Indian Council of Historical Research, New Delhi. Jaipur: Shodhak

- Patton, Laurie L. and Edwin Bryant (eds.) ( 2005) Indo-Aryan Controversy: Evidence and Inference in Indian History, London: Routledge. ISBN 0-7007-1462-6 ISBN 0-7007-1463-4

- Rishi, Weer Rajendra (1982) India & Russia: Linguistic & Cultural Affinity. Chandigarh: Roma Publications

- Sathe, Shriram (1987) Dates of the Buddha. Hyderabad: Bharatiya Itihasa Sankalana Samiti Hyderabad

- Sethna, K. D. (2000) Problems of Ancient India, New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. ISBN 81-7742-026-7

- Sethna, Kaikhushru Dhunjibhoy (1989) Ancient India in a new light. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan. ISBN 81-85179-12-3

- Shastri, Biswanarayan (ed.) and Pratap Chandra Choudhury, (1982) Abhinandana-Bhāratī: Professor Krishna Kanta Handiqui Felicitation Volume. Gauhati: Kāmarūpa Anusandhāna Samiti

- Shrava, Satya (1981 [1947]) The Śakas in India. New Delhi: Pranava Prakashan

- Singh, Acharya Phool (2002) Philosophy, religion and Vedic education, Jaipur: Sublime. ISBN 81-85809-97-6

- Singh, G. P., Dhaneswar Kalita, V. Sudarsen and Mohammed Abdul Kalam (1990) Kiratas in Ancient India: Displacement, Resettlement, Development. India University Grants Commission, Indian Council of Social Science Research. New Delhi: Gian. ISBN 81-212-0329-5

- Singh, Gursharan (ed.) (1996) Punjab history conference. Punjabi University. ISBN 81-7380-220-3 ISBN 81-7380-221-1

- Talbert, Richard J.A. (ed.) (2000) Barrington Atlas of the Greek and Roman World. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-04945-8

- Vogelsang, Willem (2001) The Afghans. Peoples of Asia Series. ISBN 978-1-4051-8243-0

- Walker, Andrew and Nicholas Tapp (2001) in Tai World: A Digest of Articles from the Thai -Yunnan Project Newsletter. Or in Scott Bamber (ed.) Thai-Yunnan Project Newsletter. Australian National University, Department of Anthropology, Research School of Pacific Studies. http://www.nectec.or.th/thai-yunnan/20.html. ISSN 1326-2777

- Witzel, M. (1999a) "Substrate Languages in Old Indo-Aryan (Rgvedic, Middle and Late Vedic)", Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies, 5:1 (September).

- Witzel, Michael (1980) "Early Eastern Iran and the Atharvaveda", Persica 9

- Witzel, Michael (1999b) "Aryan and non-Aryan Names in Vedic India. Data for the linguistic situation, c. 1900-500 B.C.", in J. Bronkhorst & M. Deshpande (eds.), Aryans and Non-Non-Aryans, Evidence, Interpretation and Ideology. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Dept. of Sanskrit and Indian Studies, Harvard University (Harvard Oriental Series, Opera Minora 3). ISBN 1-888789-04-2 pp. 337–404

- Witzel, Michael (2001) in Electronic Journal of Vedic Studies 7:3 (May 25), Article 9. ISSN 1084-7561

- Yar-Shater, Ehsan (ed.) (1983) The Cambridge History of Iran, Vol. 3: The Seleucid, Parthian and Sasanian periods. ISBN 0-521-20092-X ISBN 0-521-24693-8 (v.3/2) ISBN 0-521-24699-7 (v.3/1-2)