Pala Empire

| Pala Empire | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

The Pala Empire in Asia in 800 | ||||||||||

| Capital | Multiple

| |||||||||

| Languages | Sanskrit, Prakrit (including Pali), proto-Bengali | |||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism, Shaivite Hinduism | |||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | |||||||||

| Emperor | ||||||||||

| • | 8th century | Gopala | ||||||||

| • | 12th century | Madanapala | ||||||||

| Historical era | Classical India | |||||||||

| • | Established | 8th century | ||||||||

| • | Disestablished | 12th century | ||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||

The Pala Empire was an imperial power during the Late Classical period on the Indian subcontinent, which originated in the region of Bengal. It is named after its ruling dynasty, whose rulers bore names ending with the suffix of Pala, which meant "protector" in the ancient language of Prakrit. They were followers of the Mahayana and Tantric schools of Buddhism. The empire was founded with the election of Gopala as the emperor of Gauda in 750.[3] The Pala stronghold was located in Bengal and Bihar, which included the major cities of Pataliputra, Vikrampura, Ramvati (Varendra), Munger, Tamralipta and Jaggadala.

The Palas were astute diplomats and military conquerors. Their army was noted for its vast war elephant cavalry. Their navy performed both mercantile and defensive roles in the Bay of Bengal. The Palas were important promoters of classical Indian philosophy, literature, painting and sculpture. They built grand temples and monasteries, including the Somapura Mahavihara, and patronized the great universities of Nalanda and Vikramashila. The Proto-Bengali language developed under Pala rule. The empire enjoyed relations with the Srivijaya Empire, the Tibetan Empire and the Arab Abbasid Caliphate. Islam first appeared in Bengal during Pala rule, as a result of increased trade between Bengal and the Middle East. Abbasid coinage found in Pala archaeological sites, as well as records of Arab historians, point to flourishing mercantile and intellectual contacts. The House of Wisdom in Baghdad absorbed the mathematical and astronomical achievements of Indian civilization during this period.[4]

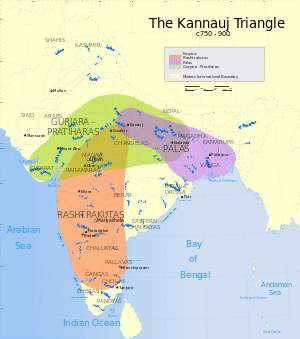

At its height in the early 9th century, the Pala Empire was the dominant power in the northern subcontinent, with its territory stretching across parts of modern-day eastern Pakistan, northern and northeastern India, Nepal and Bangladesh.[3][5] The empire reached its peak under Emperors Dharmapala and Devapala. The Palas also exerted a strong cultural influence under Atisa in Tibet, as well as in Southeast Asia. Pala control of North India was ultimately ephemeral, as they struggled with the Gurjara-Pratiharas and the Rashtrakutas for the control of Kannauj and were defeated. After a short lived decline, Emperor Mahipala I defended imperial bastions in Bengal and Bihar against South Indian Chola invasions. Emperor Ramapala was the last strong Pala ruler, who gained control of Kamarupa and Kalinga. The empire was considerably weakened by the 11th century, with many areas engulfed in rebellion.

The resurgent Hindu Sena dynasty dethroned the Pala Empire in the 12th century, ending the reign of the last major Buddhist imperial power in the subcontinent. The Pala period is considered one of the golden eras of Bengali history.[6][7] The Palas brought stability and prosperity to Bengal after centuries of civil war between warring divisions. They advanced the achievements of previous Bengali civilizations and created outstanding works of art and architecture. They laid the basis for the Bengali language, including its first literary work, the Charyapada. The Pala legacy is still reflected in Tibetan Buddhism.

History

Origins

According to the Khalimpur copper plate inscription, the first Pala king Gopala was the son of a warrior named Vapyata. The Ramacharitam attests that Varendra (North Bengal) was the fatherland (Janakabhu) of the Palas. The ethnic origins of the dynasty are unknown, although the later records claim that Gopala was a Kshatriya belonging to the legendary solar dynasty. The Ballala-Carita states that the Palas were Kshatriyas, a claim reiterated by Taranatha in his History of Buddhism in India as well as Ghanaram Chakrabarty in his Dharmamangala (both written in the 16th century CE). The Ramacharitam also attests the fifteenth Pala emperor, Ramapala, as a Kshatriya. Claims of belonging to the mythical solar dynasty are unreliable and clearly appear to be an attempt to cover up the humble origins of the dynasty.[7] The Pala dynasty has also been branded as Śudra in some sources such as Manjushri-Mulakalpa; this might be because of their Buddhist leanings.[8][9][10][11][12][13][14] According to Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak (in Ain-i-Akbari), the Palas were Kayasthas. There are even accounts that claim Gopala may have been from a Brahmin lineage.[15][16]

Establishment

After the fall of Shashanka's kingdom, the Bengal region was in a state of anarchy. There was no central authority, and there was constant struggle between petty chieftains. The contemporary writings describe this situation as matsya nyaya ("fish justice" i.e. a situation where the big fish eat the small fish). Gopala ascended the throne as the first Pala king during these times. The Khalimpur copper plate suggests that the prakriti (people) of the region made him the king.[7] Taranatha, writing nearly 800 years later, also writes that he was democratically elected by the people of Bengal. However, his account is in form of a legend, and is considered historically unreliable. The legend mentions that after a period of anarchy, the people elected several kings in succession, all of whom were consumed by the Naga queen of an earlier king on the night following their election. Gopal, however managed to kill the queen and remained on the throne.[17] The historical evidence indicates that Gopala was not elected directly by his citizens, but by a group of feudal chieftains. Such elections were quite common in contemporary societies of the region.[7][17]

Gopala's ascension was a significant political event as the several independent chiefs recognized his political authority without any struggle.[6]

Expansion under Dharmapala and Devapala

Gopala's empire was greatly expanded by his son Dharmapala and his grandson Devapala. Dharmapala was initially defeated by the Pratihara ruler Vatsaraja. Later, the Rashtrakuta king Dhruva defeated both Dharmapala and Vatsaraja. After Dhruva left for the Deccan region, Dharmapala built a mighty empire in the northern India. He defeated Indrayudha of Kannauj, and installed his own nominee Chakrayudha on the throne of Kannauj. Several other smaller states in North India also acknowledged his suzerainty. Soon, his expansion was checked by Vatsaraja's son Nagabhata II, who conquered Kannauj and drove away Chakrayudha. Nagabhata II then advanced up to Munger and defeated Dharmapala in a pitched battle. Dharmapala was forced to surrender and to seek alliance with the Rashtrakuta emperor Govinda III, who then intervened by invading northern India and defeating Nagabhata II.[18][19] The Rashtrakuta records show that both Chakrayudha and Dharmapala recognized the Rashtrakuta suzerainty. In practice, Dharmapala gained control over North India after Govinda III left for the Deccan. He adopted the title Paramesvara Paramabhattaraka Maharajadhiraja.[6]

Dharmapala was succeeded by his son Devapala, who is regarded as the most powerful Pala ruler.[6] His expeditions resulted in the invasion of Pragjyotisha (present-day Assam) where the king submitted without giving a fight and the Utkala (present-day Orissa) whose king fled from his capital city.[20] The inscriptions of his successors also claim several other territorial conquests by him, but these are highly exaggerated (see the Geography section below).[7][21]

First period of decline

Following the death of Devapala, the Pala empire gradually started disintegrating. Vigrahapala, who was Devapala's nephew, abdicated the throne after a brief rule, and became an ascetic. Vigrahapala's son and successor Narayanapala proved to be a weak ruler. During his reign, the Rashtrakuta king Amoghavarsha defeated the Palas. Encouraged by the Pala decline, the King Harjara of Assam assumed imperial titles and the Sailodbhavas established their power in Orissa.[6]

Naryanapala's son Rajyapala ruled for at least 12 years, and constructed several public utilities and lofty temples. His son Gopala II lost Bengal after a few years of rule, and then ruled only Bihar. The next king, Vigrahapala II, had to bear the invasions from the Chandelas and the Kalachuris. During his reign, the Pala empire disintegrated into smaller kingdoms like Gauda, Radha, Anga and Vanga. Kantideva of Harikela (eastern and southern Bengal) also assumed the title Maharajadhiraja, and established a separate kingdom, later ruled by the Chandra dynasty.[6] The Gauda state (West and North Bengal) was ruled by the Kamboja Pala dynasty. The rulers of this dynasty also bore names ending in the suffix -pala (e.g. Rajyapala, Narayanapala and Nayapala). However, their origin is uncertain, and the most plausible view is that they originated from a Pala official who usurped a major part of the Pala kingdom along with its capital.[6][7]

Revival under Mahipala I

Mahipala I recovered northern and eastern Bengal within three years of ascending the throne in 988 CE. He also recovered the northern part of the present-day Burdwan division. During his reign, Rajendra Chola I of the Chola Empire frequently invaded Bengal from 1021 to 1023 CE in order to get Ganges water and in the process, succeeded to humble the rulers, acquiring considerable booty. The rulers of Bengal who were defeated by Rajendra Chola were Dharmapal, Ranasur and Govindachandra, who might have been feudatories under Mahipala I of the Pala Dynasty.[22] Rajendra Chola I also defeated Mahipala, and obtained from the Pala king "elephants of rare strength, women and treasure".[23] Mahipala also gained control of north and south Bihar, probably aided by the invasions of Mahmud of Ghazni, which exhausted the strength of other rulers of North India. He may have also conquered Varanasi and surrounding area, as his brothers Sthirapala and Vasantapala undertook construction and repairs of several sacred structures at Varanasi. Later, the Kalachuri king Gangeyadeva annexed Varanasi after defeating the ruler of Anga, which could have been Mahipala I.[6]

Second period of decline

Nayapala, the son of Mahipala I, defeated the Kalachuri king Karna (son of Ganggeyadeva) after a long struggle. The two later signed a peace treaty at the mediation of the Buddhist scholar Atiśa. During the reign of Nayapala's son Vigrahapala III, Karna once again invaded Bengal but was defeated. The conflict ended with a peace treaty, and Vigrahapala III married Karna's daughter Yauvanasri. Vigrahapala III was later defeated by the invading Chalukya king Vikramaditya VI. The invasion of Vikramaditya VI saw several soldiers from South India into Bengal, which explains the southern origin of the Sena Dynasty.[24] Vigrahapala III also faced another invasion led by the Somavamsi king Mahasivagupta Yayati of Orissa. Subsequently, a series of invasions considerably reduced the power of the Palas. The Varmans occupied eastern Bengal during his reign.[6][7]

Mahipala II, the successor of Vigrahapala III, brought a short-lived reign of military glory. His reign is well-documented by Sandhyakar Nandi in Ramacharitam. Mahipala II imprisoned his brothers Ramapala and Surapala II, on the suspicion that they were conspiring against him. Soon afterwards, he faced a rebellion of vassal chiefs from the Kaibarta (fishermen). A chief named Divya (or Divvoka) killed him and occupied the Varendra region. The region remained under the control of his successors Rudak and Bhima. Surapala II escaped to Magadha and died after a short reign. He was succeeded by his brother Ramapala, who launched a major offensive against Divya's grandson Bhima. He was supported by his maternal uncle Mathana of the Rashtrakuta dynasty, as well as several feudatory chiefs of south Bihar and south-west Bengal. Ramapala conclusively defeated Bhima, and killing him and his family in a cruel manner.[6][7]

Revival under Ramapala

After gaining control of Varendra, Ramapala tried to revive the Pala empire with limited success. He ruled from a new capital at Ramavati, which remained the Pala capital until the dynasty's end. He reduced taxation, promoted cultivation and constructed public utilities. He brought Kamarupa and Rar under his control, and forced the Varman king of east Bengal to accept his suzerainty. He also struggled with the Ganga king for control of present-day Orissa; the Gangas managed to annex the region only after his death. Ramapala maintained friendly relations with the Chola king Kulottunga to secure support against the common enemies: the Ganas and the Chalukyas. He kept the Senas in check, but lost Mithila to a Karnataka chief named Nanyuadeva. He also held back the aggressive design of the Gahadavala ruler Govindacharndra through a matrimonial alliance.[6][7]

Final decline

Ramapala was the last strong Pala ruler. After his death, a rebellion broke out in Assam during his son Kumarapala's reign. The rebellion was crushed by Vaidyadeva, but after Kumarapala's death, Vaidyadeva practically created a separate kingdom.[6] According to Ramacharitam, Kumarapala's son Gopala III was murdered by his uncle Mandapala. During Madanapala's rule, the Varmans in east Bengal declared independence, and the Eastern Gangas renewed the conflict in Orissa. Madanapala captured Munger from the Gahadavalas, but was defeated by Vijayasena, who gained control of southern and eastern Bengal. A ruler named Govindapala ruled over the Gaya district around 1162 CE, but there is no concrete evidence about his relationship to the imperial Palas. The Pala dynasty was replaced by the Sena dynasty.[7]

Geography

The borders of the Pala Empire kept fluctuating throughout its existence. Though the Palas conquered a vast region in North India at one time, they could not retain it for long due to constant hostility from the Gurjara-Pratiharas, the Rashtrakutas and other less powerful kings.[25]

No records are available about the exact boundaries of original kingdom established by Gopala, but it might have included almost all of the Bengal region.[6] The Pala empire extended substantially under Dharmapala's rule. Apart from Bengal, he directly ruled the present-day Bihar. The kingdom of Kannauj (present-day Uttar Pradesh) was a Pala dependency at times, ruled by his nominee Chakrayudha.[6] While installing his nominee on the Kannauj throne, Dharmapala organized an imperial court. According to the Khalimpur copper plate issued by Dharmapala, this court was attended by the rulers of Bhoja (possibly Vidarbha), Matsya (Jaipur region), Madra (East Punjab), Kuru (Delhi region), Yadu (possibly Mathura, Dwarka or Simhapura in the Punjab), Yavana, Avanti, Gandhara and Kira (Kangra Valley).[7][26] These kings accepted the installation of Chakrayudha on the Kannauj throne, while "bowing down respectfully with their diadems trembling".[27] This indicates that his position as a sovereign was accepted by most rulers, although this was a loose arrangement unlike the empire of the Mauryas or the Guptas. The other rulers acknowledged the military and political supremacy of Dharmapala, but maintained their own territories.[7] The poet Soddhala of Gujarat calls Dharmapala an Uttarapathasvamin ("Lord of the North") for his suzerainty over North India.[28]

The epigraphic records credit Devapala with extensive conquests in hyperbolic language. The Badal pillar inscription of his successor Narayana Pala states that by the wise counsel and policy of his Brahmin minister Darbhapani, Devapala became the suzerain monarch or Chakravarti of the whole tract of Northern India bounded by the Vindhyas and the Himalayas. It also states that his empire extended up to the two oceans (presumably the Arabian Sea and the Bay of Bengal). It also claims that Devpala defeated Utkala (present-day Orissa), the Hunas, the Kambojas, the Dravidas, the Kamarupa (present-day Assam), and the Gurjaras:[6]

- The Gurjara adversary may have been Mihira Bhoja, whose eastward expansion was checked by Devapala

- The identity of the Huna king is uncertain.

- The identity of the Kamboja prince is also uncertain. While an ancient country with the name Kamboja was located in what is now Afghanistan, there is no evidence that Devapala's empire extended that far. Kamboja, in this inscription, could refer to the Kamboja tribe that had entered North India (see Kamboja Pala dynasty).

- The Dravida king is usually identified with the Rashtrakuta king Amoghavarsha. Some scholars believe that the Dravida king could have been the Pandya ruler Shri Mara Shri Vallabha, since "Dravida" usually refers to the territory south of the Krishna river. According to this theory, Devapala could have been helped in his southern expedition by the Chandela king Vijaya. In any case, Devapala's gains in the south, if any, were temporary.

The claims about Devapala's victories are exaggerated, but cannot be dismissed entirely: there is no reason to doubt his conquest of Utkala and Kamarupa. Besides, the neighbouring kingdoms of Rashtrakutas and the Gurjara-Pratiharas were weak at the time, which might have helped him extend his empire.[21] Devapala is also believed to have led an army up to the Indus river in Punjab.[6]

The empire started disintegrated after the death of Devapala, and his successor Narayanapala lost control of Assam and Orissa. He also briefly lost control over Magadha and north Bengal. Gopala II lost control of Bengal, and ruled only from a part of Bihar. The Pala empire disintegrated into smaller kingdoms during the reign of Vigrahapala II. Mahipala recovered parts of Bengal and Bihar. His successors lost Bengal again. The last strong Pala ruler, Ramapala, gained control of Bengal, Bihar, Assam and parts of Orissa.[6] By the time of Madanapala's death, the Pala kingdom was confined to parts of central and east Bihar along with northern Bengal.[6]

Administration

The Pala rule was monarchial. The king was the centre of all power. Pala kings would adopt imperial titles like Parameshwara, Paramvattaraka, Maharajadhiraja. Pala kings appointed Prime Ministers. The Line of Garga served as the Prime Ministers of the Palas for 100 years.

- Garga

- Darvapani (or Darbhapani)

- Someshwar

- Kedarmisra

- Bhatta Guravmisra

Pala Empire was divided into separate Bhuktis (Provinces). Bhuktis were divided into Vishayas (Divisions) and Mandalas (Districts). Smaller units were Khandala, Bhaga, Avritti, Chaturaka, and Pattaka. Administration covered widespread area from the grass root level to the imperial court.[29]

The Pala copperplates mention following administrative posts:[30]

- Raja

- Rajanyaka

- Ranaka (possibly subordinate chiefs)

- Samanta and Mahasamanta (Vassal kings)

- Mahasandhi-vigrahika (Foreign minister)

- Duta (Head Ambassador)

- Rajasthaniya (Deputy)

- Aggaraksa (Chief guard)

- Sasthadhikrta (Tax collector)

- Chauroddharanika (Police tax)

- Shaulkaka (Trade tax)

- Dashaparadhika (Collector of penalties)

- Tarika (Toll collector for river crossings)

- Mahaksapatalika (Accountant)

- Jyesthakayastha (Dealing documents)

- Ksetrapa (Head of land use division) and Pramatr (Head of land measurements)

- Mahadandanayaka or Dharmadhikara (Chief justice)

- Mahapratihara

- Dandika

- Dandapashika

- Dandashakti (Police forces)

- Khola (Secret service). Agricultural posts like Gavadhakshya (Head of dairy farms)

- Chhagadhyakshya (Head of goat farms)

- Meshadyakshya (Head of sheep farms)

- Mahishadyakshya (Head of Buffalo farms) and many other like Vogpati

- Vishayapati

- Shashtadhikruta

- Dauhshashadhanika

- Nakadhyakshya

Culture

Religion

The Palas were patrons of Mahayana Buddhism. A few sources written much after Gopala's death mention him as a Buddhist, but it is not known if this is true.[31] The subsequent Pala kings were definitely Buddhists. Taranatha states that Gopala was a staunch Buddhist, who had built the famous monastery at Odantapuri.[32] Dharmapala made the Buddhist philosopher Haribhadra his spiritual preceptor. He established the Vikramashila monastery and the Somapura Mahavihara. Taranatha also credits him with establishing 50 religious institutions and patronizing the Buddhist author Hariibhadra. Devapala restored and enlarged the structures at Somapura Mahavihara, which also features several themes from the epics Ramayana and Mahabharata. Mahipala I also ordered construction and repairs of several sacred structures at Saranath, Nalanda and Bodh Gaya.[6] The Mahipala geet ("songs of Mahipala"), a set of folk songs about him, are still popular in the rural areas of Bengal.

The Palas developed the Buddhist centers of learnings, such as the Vikramashila and the Nalanda universities. Nalanda, considered one of the first great universities in recorded history, reached its height under the patronage of the Palas. Noted Buddhist scholars from the Pala period include Atisha, Santaraksita, Saraha, Tilopa, Bimalamitra, Dansheel, Dansree, Jinamitra, Jnanasrimitra, Manjughosh, Muktimitra, Padmanava, Sambhogabajra, Shantarakshit, Silabhadra, Sugatasree and Virachan.

As the rulers of Gautama Buddha's land, the Palas acquired great reputation in the Buddhist world. Balaputradeva, the Sailendra king of Java, sent an ambassador to him, asking for a grant of five villages for the construction of a monastery at Nalanda.[33] The request was granted by Devapala. He appointed the Brahmin Viradeva (of Nagarahara, present-day Jalalabad) as the head of the Nalanda monastery. The Budhdist poet Vajradatta (the author of Lokesvarashataka), was in his court.[6] The Buddhist scholars from the Pala empire travelled from Bengal to other regions to propagate Buddhism. Atisha, for example, preached in Tibet and Sumatra, and is seen as one of the major figures in the spread of 11th-century Mahayana Buddhism.

The Palas also supported the Saiva ascetics, typically the ones associated with the Golagi-Math.[34] Narayana Pala himself established a temple of Shiva, and was present at the place of sacrifice by his Brahmin minister.[35] Queen of King Madanapaladeva, namely Chitramatika, made a gift of land to a Brahmin named Bateswara Swami as his remuneration for chanting the Mahabharata at her request, according to the principle of the Bhumichhidranyaya. Besides the images of the Buddhist deities, the images of Vishnu, Siva and Sarasvati were also constructed during the Pala dynasty rule.[36]

Literature

The Palas patronized several Sanskrit scholars, some of whom were their officials. The Gauda riti style of composition was developed during the Pala rule. Many Buddhist Tantric works were authored and translated during the Pala rule. Besides the Buddhist scholars mentioned in the Religion section above, Jimutavahana, Sandhyakar Nandi, Madhava-kara, Suresvara and Chakrapani Datta are some of the other notable scholars from the Pala period.[6]

The notable Pala texts on philosophy include Agama Shastra by Gaudapada, Nyaya Kundali by Sridhar Bhatta and Karmanushthan Paddhati by Bhatta Bhavadeva. The texts on medicine include

- Chikitsa Samgraha, Ayurveda Dipika, Bhanumati, Shabda Chandrika and Dravya Gunasangraha by Chakrapani Datta

- Shabda-Pradipa, Vrikkhayurveda and Lohpaddhati by Sureshwara

- Chikitsa Sarsamgraha by Vangasena

- Sushrata by Gadadhara Vaidya

- Dayabhaga, Vyavohara Matrika and Kalaviveka by Jimutavahana

Sandhyakar Nandi's semi-fictional epic Ramacharitam (12th century) is an important source of Pala history.

A form of the proto-Bengali language can be seen in the Charyapadas composed during the Pala rule.[6]

Art and architecture

The Pala school of sculptural art is recognised as a distinct phase of the Indian art, and is noted for the artistic genius of the Bengal sculptors.[37] It is influenced by the Gupta art.[38]

Carved shankhas

Carved shankhas Sculpture of Khasarpana Lokesvara from Nalanda

Sculpture of Khasarpana Lokesvara from Nalanda

As noted earlier, the Palas built a number of monasteries and other sacred structures. The Somapura Mahavihara in present-day Bangladesh is a World Heritage Site. It is a monastery with 21 acre (85,000 m²) complex has 177 cells, numerous stupas, temples and a number of other ancillary buildings. The gigantic structures of other Viharas, including Vikramashila, Odantapuri, and Jagaddala are the other masterpieces of the Palas. These mammoth structures were mistaken by the forces of Bakhtiar Khilji as fortified castles and were demolished. The art of Bihar and Bengal during the Pala and Sena dynasties influenced the art of Nepal, Burma, Sri Lanka and Java.[39]

Somapura Mahavihara, a World Heritage Site, was built by Dharmapala

Somapura Mahavihara, a World Heritage Site, was built by Dharmapala Central shrine decor at Somapura

Central shrine decor at Somapura A model of the Somapura Mahavihara by Ali Naqi

A model of the Somapura Mahavihara by Ali Naqi Ruins of Vikramashila

Ruins of Vikramashila

List of Pala rulers

Most of the Pala inscriptions mention only the regnal year as the date of issue, without any well-known calendar era. Because of this, the chronology of the Pala kings is hard to determine.[40] Based on their different interpretations of the various epigraphs and historical records, different historians estimate the Pala chronology as follows:[41]

| RC Majumdar (1971)[42] | AM Chowdhury (1967)[43] | BP Sinha (1977)[44] | DC Sircar (1975–76)[45] | D. K. Ganguly (1994)[40] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gopala I | 750–770 | 756–781 | 755–783 | 750–775 | 750-774 |

| Dharmapala | 770–810 | 781–821 | 783–820 | 775–812 | 774-806 |

| Devapala | 810–c. 850 | 821–861 | 820–860 | 812–850 | 806-845 |

| Mahendrapala | NA (Mahendrapala's existence was conclusively established through a copper-plate charter discovered later.) | 845-860 | |||

| Shurapala I | 850–853 | 861–866 | 860–865 | 850–858 | 860-872 |

| Vigrahapala I | 858–60 | 872-873 | |||

| Narayanapala | 854–908 | 866–920 | 865–920 | 860–917 | 873-927 |

| Rajyapala | 908–940 | 920–952 | 920–952 | 917–952 | 927-959 |

| Gopala II | 940–957 | 952–969 | 952–967 | 952–972 | 959-976 |

| Vigrahapala II | 960–c. 986 | 969–995 | 967–980 | 972–977 | 976-977 |

| Mahipala I | 988–c. 1036 | 995–1043 | 980–1035 | 977–1027 | 977-1027 |

| Nayapala | 1038–1053 | 1043–1058 | 1035–1050 | 1027–1043 | 1027-1043 |

| Vigrahapala III | 1054–1072 | 1058–1075 | 1050–1076 | 1043–1070 | 1043–1070 |

| Mahipala II | 1072–1075 | 1075–1080 | 1076–1078/9 | 1070–1071 | 1070-1071 |

| Shurapala | 1075–1077 | 1080–1082 | 1071–1072 | 1071-1072 | |

| Ramapala | 1077–1130 | 1082–1124 | 1078/9–1132 | 1072–1126 | 1072-1126 |

| Kumarapala | 1130–1125 | 1124–1129 | 1132–1136 | 1126–1128 | 1126–1128 |

| Gopala III | 1140–1144 | 1129–1143 | 1136–1144 | 1128–1143 | 1128–1143 |

| Madanapala | 1144–1162 | 1143–1162 | 1144–1161/62 | 1143–1161 | 1143–1161 |

| Govindapala | 1155–1159 | NA | 1162–1176 or 1158–1162 | 1161–1165 | 1161–1165 |

| Palapala | NA | NA | NA | 1165–1199 | 1165–1200 |

Note:[41]

- Earlier historians believed that Vigrahapala I and Shurapala I were the two names of the same person. Now, it is known that these two were cousins; they either ruled simultaneously (perhaps over different territories) or in rapid succession.

- AM Chowdhury rejects Govindapala and his successor Palapala as the members of the imperial Pala dynasty.

- According to BP Sinha, the Gaya inscription can be read as either the "14th year of Govindapala's reign" or "14th year after Govindapala's reign". Thus, two sets of dates are possible.

Military

The highest military officer in the Pala empire was the Mahasenapati (commander-in-chief). The Palas recruited mercenary soldiers from a number of kingdoms, including Malava, Khasa, Huna, Kulika, Kanrata, Lata, Odra and Manahali. According to the contemporary accounts, the Rashtrakutas had the best infantry, the Gurjara-Pratiharas had the finest cavalry and the Palas had the largest elephant force. The Arab merchant Sulaiman states that the Palas had an army bigger than those of the Balhara (possibly the Rashtrakutas) and the king of Jurz (possibly the Gurjara-Pratiharas). He also states that the Pala army employed 10,000-15,000 men for fueling and washing clothes. He further claims that during the battles, the Pala king would lead 50,000 war elephants. Sulaiman's accounts seem to be based on exaggerated reports; Ibn Khaldun mentions the number of elephants as 5,000.[46]

Since Bengal did not have a good native breed of horses, the Palas imported their cavalry horses from the foreigners, including the Kambojas. They also had a navy, used for both mercantile and defence purposes.[47]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pala Empire. |

Sources

The main sources of information about the Pala empire include:[48]

- Pala accounts

- Various epigraphs, coins, sculptures and architecture

- Ramacharita, a Sanskrit work by Abhinanda (9th century)

- Ramacharitam, a Sanskrit epic by Sandhyakar Nandi (12th century)

- Subhasita Ratnakosa, a Sanskrit compilation by Vidyakara (towards the end of the Pala rule)

- Other accounts

- Silsiltut-Tauarikh by the Arab merchant Suleiman (951 CE), who referred to the Pala kingdom as Ruhmi or Rahma

- Dpal dus khyi 'khor lo'i chos bskor gyi byung khungs nyer mkh (History of Buddhism in India) by Taranatha (1608), contains a few traditional legends and hearsays about the Pala rule

- Ain-i-Akbari by Abu'l-Fazl (16th-century)

References

- ↑ Michael C. Howard (2012). Transnationalism in Ancient and Medieval Societies: The Role of Cross-Border Trade and Travel. McFarland. p. 72. ISBN 978-0-7864-9033-2.

- ↑ Huntington 1984, p. 56.

- 1 2 R. C. Majumdar (1977). Ancient India. Motilal Banarsidass Publ. pp. 268–. ISBN 978-81-208-0436-4.

- ↑ Raj Kumar (2003). Essays on Ancient India. Discovery Publishing House. p. 199. ISBN 978-81-7141-682-0.

- ↑ Sailendra Nath Sen (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. pp. 280–. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Sailendra Nath Sen (1999). Ancient Indian History and Civilization. New Age International. pp. 277–287. ISBN 978-81-224-1198-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Sengupta 2011, pp. 39-49.

- ↑ Bagchi 1993, p. 37.

- ↑ Vasily Vasilyev (December 1875). Translated by E. Lyall. "Taranatea's Account of the Magadha Kings" (PDF). The Indian Antiquary. IV: 365–66.

- ↑ Ramaranjan Mukherji; Sachindra Kumar Maity (1967). Corpus of Bengal Inscriptions Bearing on History and Civilization of Bengal. Calcutta: Firma K.L. Mukhopadhyay. p. 11.

- ↑ J. C. Ghosh (1939). "Caste and Chronology of the Pala Kings of Bengal". The Indian Historical Quarterly. IX (2): 487–90.

- ↑ The Caste of the Palas, The Indian Culture, Vol IV, 1939, pp 113–14, B Chatterji

- ↑ M. N. Srinivas (1995). Social Change in Modern India. Orient Blackswan. p. 9. ISBN 978-81-250-0422-6.

- ↑ Metcalf, Thomas R. (1971). Modern India: An Interpretive Anthology. Macmillan. p. 115.

- ↑ André Wink (1990). Al-Hind, the Making of the Indo-Islamic World. BRILL. p. 265. ISBN 90-04-09249-8.

- ↑ Ishwari Prasad (1940). History of Mediaeval India. p. 20 fn.

- 1 2 Biplab Dasgupta (2005). European Trade and Colonial Conquest. Anthem Press. pp. 341–. ISBN 978-1-84331-029-7.

- ↑ John Andrew Allan; Sir T. Wolseley Haig (1934). The Cambridge Shorter History of India. Macmillan Company. p. 143.

- ↑ Bindeshwari Prasad Sinha (1977). Dynastic History of Magadha. Abhinav Publications. p. 179. ISBN 978-81-7017-059-4.

- ↑ Bhagalpur Charter of Narayanapala, year 17, verse 6, The Indian Antiquary, XV p 304.

- 1 2 Bindeshwari Prasad Sinha (1977). Dynastic History of Magadha. Abhinav Publications. p. 185. ISBN 978-81-7017-059-4.

- ↑ Sengupta 2011, p. 45.

- ↑ John Keay (2000). India: A History. Grove Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-8021-3797-5.

- ↑ John Andrew Allan; Sir T. Wolseley Haig (1934). The Cambridge Shorter History of India. Macmillan Company. p. 10.

- ↑ Bagchi 1993, p. 4.

- ↑ Bindeshwari Prasad Sinha (1977). Dynastic History of Magadha. Abhinav Publications. pp. 177–. ISBN 978-81-7017-059-4.

- ↑ Paul 1939, p. 38.

- ↑ Bagchi 1993, p. 39–40.

- ↑ Paul 1939, p. 122–124.

- ↑ Paul 1939, p. 111–122.

- ↑ Huntington 1984, p. 39.

- ↑ Taranatha (1869). Târanâtha's Geschichte des Buddhismus in Indien [History of Buddhism in India] (in German). Translated by Anton Schiefner. St. Petersburg: Imperial Academy of Sciences. p. 206.

Zur Zeit des Königs Gopâla oder Devapâla wurde auch das Otautapuri-Vihâra errichtet.

- ↑ P. N. Chopra; B. N. Puri; M. N. Das; A. C. Pradhan, eds. (2003). A Comprehensive History of Ancient India (3 Vol. Set). Sterling. pp. 200–202. ISBN 978-81-207-2503-4.

- ↑ Bagchi 1993, p. 19.

- ↑ Bagchi 1993, p. 100.

- ↑ Krishna Chaitanya (1987). Arts of India. Abhinav Publications. p. 38. ISBN 978-81-7017-209-3.

- ↑ Chowdhury, AM (2012). "Pala Dynasty". In Islam, Sirajul; Jamal, Ahmed A. Banglapedia: National Encyclopedia of Bangladesh (Second ed.). Asiatic Society of Bangladesh.

- ↑ Rustam Jehangir Mehta (1981). Masterpieces of Indian bronzes and metal sculpture. Taraporevala. p. 21.

- ↑ Stella Kramrisch (1994). Exploring India's Sacred Art Selected Writings of Stella Kramrisch. Motilal Banarsidass Publishe. p. 208. ISBN 978-81-208-1208-6.

- 1 2 Dilip Kumar Ganguly (1994). Ancient India, History and Archaeology. Abhinav. pp. 33–41. ISBN 978-81-7017-304-5.

- 1 2 Susan L. Huntington (1984). The "Påala-Sena" Schools of Sculpture. Brill Archive. pp. 32–39. ISBN 90-04-06856-2.

- ↑ R. C. Majumdar (1971). History of Ancient Bengal. G. Bharadwaj. p. 161–162.

- ↑ Abdul Momin Chowdhury (1967). Dynastic history of Bengal, c. 750-1200 CE. Asiatic Society of Pakistan. pp. 272–273.

- ↑ Bindeshwari Prasad Sinha (1977). Dynastic History of Magadha, Cir. 450–1200 A.D. Abhinav Publications. pp. 253–. ISBN 978-81-7017-059-4.

- ↑ Dineshchandra Sircar (1975–76). "Indological Notes - R.C. Majumdar's Chronology of the Pala Kings". Journal of Indian History. IX: 209–10.

- ↑ Paul 1939, p. 139–143.

- ↑ Paul 1939, p. 143–144.

- ↑ Bagchi 1993, pp. 2-3.

Bibliography

- Bagchi, Jhunu (1993). The History and Culture of the Pālas of Bengal and Bihar, Cir. 750 A.D.-cir. 1200 A.D. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-301-4.

- Huntington, Susan L. (1984). The "Påala-Sena" Schools of Sculpture. Brill Archive. ISBN 90-04-06856-2.

- Paul, Pramode Lal (1939). The Early History of Bengal. Indian History. 1. Indian Research Institute. Retrieved 2014-03-28.

- Sengupta, Nitish K. (2011). Land of Two Rivers: A History of Bengal from the Mahabharata to Mujib. Penguin Books India. pp. 39–49. ISBN 978-0-14-341678-4.