Architecture of Mongolia

The architecture of Mongolia is based on traditional dwellings such as the yurt (Mongolian: гэр, ger) and tent. In the 16th and 17th centuries, Lamaseries were built throughout the country as structures used for temples. These temples were later enlarged to accommodate the growing number of worshipers. Mongolian architects designed their temples with 6 and 12 angles, also sporting pyramidal roofs to approximate the round shape of the traditional yurt. Further expansion led to a quadratic shape in the design of the temples. Thus roofs were made in the shape of marquees.[1]

The trellis walls, roof poles and layers of felt were eventually replaced by stone and brick beams and planks, which became permanent.[2]

Chultem distinguished three styles in traditional Mongolian architecture: Mongolian, Tibetan and Chinese, as well as combinations thereof. Batu-Tsagaan (1654) designed by Zanabazar was one of the first quadratic temples. The Dashchoilin khiid monastery in Ulaanbaatar is an example of yurt-style architecture. The Lavrin temple (18th century) in the Erdene Zuu lamasery was built in the Tibetan tradition. The Choijin Lama Süm temple (1904) is an example of a temple built in the Chinese tradition. It is a museum today. The quadratic Tsogchin temple in Gandan monastery in Ulaanbaatar is a combination of the Mongolian and Chinese traditions. The Maitreya temple (disassembled in 1938) was an example of the Tibeto-Mongolian architecture.[1] Dashchoilin khiid has commenced a project to restore this temple and the 80-feet sculpture of Maitreya. Indian influences can also be seen in Mongolian architecture, especially in the designs of Buddhist stupas.

Socialist-era Mongolian architects occasionally incorporated traditional elements, such as round shapes (e.g. restaurants Tuyaa (nowadays "Seoul") and Khorshoolol (nowadays "KhanBräu")) or meandering ornaments (on many of the residential tower blocks).

Ancient Period

The Xiongnu culture ruled the area that is now Mongolia from the 3rd century BCE through the 1st century. Their dwellings consisted of portable round-shaped tents on carts and round yurts. The Xiongnu aristocracy lived in small palaces, and their villages were protected by huge walls.[3] S. I. Rudenko also mentions capital construction built of logs.[4] Archaeological excavations have indicated that the Xiongnu had towns.[5] Their main city was called Luut Hot (City of Dragon).

Powerful statehoods built by Turkic and Uigur tribes, from the 6th through the 9th centuries, dominated what is now Mongolia. Several Turkic cities and towns existed in the basin of the rivers Orhon, Tuul and Selenge.[5] The main city of the Turkic Kaganate was Balyklyk. The Uigur Kaganate that succeeded the Turks centered on the city Kara Balgasun founded in the early 8th century. A fragment of the twelve metre high fortress wall with a watch tower has been preserved. A large trades-and-craftswork district existed in the city.[5] Their architecture was influenced by the Sogdian and Chinese traditions.[1] The Uigur Kaganate was routed by their warlike neighbours Kirghiz, who destroyed the advanced culture of the Uigur, and the cultural development of the country was thrown back to the primitive stage.

Archaeological excavations discovered traces of cities of the Kidan period that lasted from the 10th to the 12th centuries. The most significant of the excavated cities was Hatun Hot founded in 944. Another significant Kidan city was Bars-Hot existed in the basin of the river Kerulen, occupying an area of 1600 x 1810 metros, surrounded with mud walls which are today 4 metres thick and 1.5–2 metres high.[1] A remnant of one of two original stupas exists today, having been damaged in the 1940s by a Soviet garrison using cannon fire to destroy one stupa for amusement.

-

Construction materials from the Xiongnu walled town of Tereljiin Dorvoljin (209BC-93AD) located within the sphere of larger Ulan Bator.

-

Gokturk Period (555-745) construction materials from memorial complex in Orkhon valley, central Mongolia.

-

Mid-7th century Gokturk door parts from memorial complex in north-central Mongolia.

-

Ordu-Baliq capital of the Uyghur Khaganate (745-840) in Mongolia.

-

Construction material from Uyghur period Durvuljin tombs, central Mongolia.

-

Construction materials from the Uyghur period Durvuljin tombs, central Mongolia.

-

Construction materials from the 10th century Khitan city Chin Tolgoi (possibly Zhenzhou), Bulgan Province, northern Mongolia.

-

Construction materials from the 10th century Khitan city Chin Tolgoi (possibly Zhenzhou), Bulgan Province, northern Mongolia.

-

Ikh Aurug Ord. 12th century capital of Khamag Mongol (1125-1206)

-

Construction material from Ikh Aurug Ord. 12th century capital of Khamag Mongol (1125-1206)

-

Remains of Wang Khan's 12th-century palace in Ulan Bator.

-

Remains of Wang Khan's 12th-century palace in Ulan Bator.

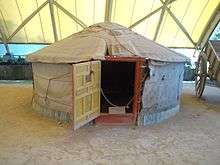

Yurts

The yurt is the traditional dwelling of the Mongolian nomads. Yurts are circular structures supported by a collapsible wooden frame, covered with wool felt. In Mongolia, a "yurt" is called a "ger" (Mongolian: гэр).

In the 12th and 13th centuries, ger-tereg (yurts on carts) were built for the khans and chieftains. Iron bushes of enormous dimensions for the shafts of a cart were found during excavations of Karakorum.[6] The distance between the wheels of such a cart would be over 6 metres and it would be pulled by 22 oxen. Such ger-teregs are mentioned in the Secret History of the Mongols.

A common arrangement of a yurt camp in medieval Mongolia was huree (kuren) (meaning "circle"), in which the yurt of the khan or chieftain was located in the centre; the yurts of other members of the tribe were placed around it. This arrangement had a defensive function during frequent skirmishes. Huree was replaced by ail (meaning "neighbourhood") arrangement in the 13th and 14th centuries during the unified Mongol Khanate when internal wars had stopped. After the disintegration of the Mongol Khanate in the 15th century, Huree arrangement was used as the basic layout of monasteries initially founded as mobile monasteries. Another type of monastery layout is known as "khiid" following the Tibetan arrangement) in the 16th and 17th centuries when Buddhism was re-introduced to the region. As huree-monasteries and huree-camps of nobles settled and developed into towns and cities, the names of such settlements retained the word huree (e.g., Niislel Huree, Zasagtu Khaan-u Huree).

Originally, roofs had steeper slopes with a rim around the center opening, to allow the smoke from central open fires to exit more easily. In the 18th and 19th centuries, enclosed stoves with chimneys (zuuh) were introduced, making it possible to simplify the design with a lower silhouette. Another relatively recent development is the use of an additional layer of canvas for rain protection. A white cotton cover, originally only used on the yurts of nobles, became commonplace.

The organization and furnishings of the interior spaces mirror traditional roles of the family members as well as spiritual concepts, giving significance to each of the cardinal directions, with the door always facing south. Herders use the position of the sun in the crown of the yurt as a sundial. The northeastern quarter of the yurt is reserved for women. Men were traditionally prohibited to enter this quarter.

Yurts have been used in Central Asia for thousands of years. In Mongolia, yurts have influenced other architectural forms, particularly temples.

In the 21st century, between 30% and 40% of the population live in yurts, many of them in the suburbs of cities. The Mongolian word "ger" has additional connotations of "home". The stylistically elevated register for ger is örgöö, most commonly translated as "residence" or "palace".

Tents

Tents also play a role in the history and development of Mongolian architecture. These temporary shelters, were used more frequently in pastoral conditions. Tents were also erected during Naadam festivals, feasts and other gatherings.

- Jodgor is a small tent to accommodate one or two persons.

- Maihan is a large tent for a group of people.

- Tsatsar is a fabric shade on vertical supports without vertical walls.

- Tsachir is a large rectangular tent with vertical fabric walls.

- Asar is a generic name for tsatsar and tsachir.

Giovanni da Pian del Carpine ("History of the Mongols") reported that during the enthronement ceremony of Guyuk Khaan in 1246, a colossal marquee-tsachir, capable of hosting 2000 people, was erected at the Tamir river. The marquee was supported by pillars decorated in gold leaves, and the internal side of the walls were covered with canopy.

Later, the designs of many temples were based on tsachir.

Imperial Period

The remains of Karakorum, capital of the Mongol Empire, were first rediscovered and studied by the expedition of S. V Kiselev. Karakorum was founded in the basin of the Orkhon River by Chinggis Khaan in 1220 as a major military centre. However, in 15 years it became an administrative and cultural centre of the empire.

In the centre of the city was situated the palace of the Great Khaan—the Tumen Amugulang palace. Based on the records of William of Rubruck, most scholars maintain that in front of the palace was the Silver Tree fountain. However, there is a group of researchers who conclude that the famous fountain was inside the palace. According to Rubruck, there were 4 silver sculptures of lions at the foot of the Silver Tree, and fermented mare's milk—airag, favourite drink of the Mongols, would run from their mouths. Four golden serpents twined round the tree. Wine would run out from the mouth of one serpent, airag—from the mouth of the second serpent, mead from the third, and rice beer from the fourth. The top of the tree was crowned by an angel blowing a bugle. The branches, leaves and fruits of the tree were all made of silver. The fountain was designed by a captive sculptor William of Paris. The Khaan himself would sit on the throne in the north of the yard in front of the palace. Men would sit in a row at the right hand of the Khaan and women would sit to the left.

Excavations partly proved and partly supplemented these descriptions. The buildings were heated by smoke pipes installed under the floors. The Khaan's palace was erected on an artificial platform occupying an area of 2475 sq. metres.

Ogedei Khaan ordered that each of his brothers, sons and other princes build a magnificent palace in Karakorum. The city hosted Buddhist temples, Christian churches and Muslim mosques. There were sculptures of tortoises at each gate on the four sides of the city wall. Steles on the backs of the tortoises were crowned with beacons for travellers in the steppe. The overall construction in Karakorun was supervised by Otchigin, the youngest brother of Genghis Khan.

There were many other cities and palaces throughout Mongolia in the 13th and 14th centuries. Best studied are the ruins of Palace Aurug near Kerulen and Hirhira and Kondui cities in the Trans-Baikal region. The latter two demonstrate that cities grew out not only around the Khaan's palaces but also around residences of the other members of nobility. City Hirhira sprang out around the residence of Juchi-Khasar. The Mongolian aristocrats were dissatisfied with temporary residences and started building luxurious palaces. The palace in Hirhira city was located within a citadel. The palace in Kondui city was built on a platform, surrounded by double-tiered terraces, pavilions and water pools. The archeological excavations revealed traces of conflagrations and the times of the fall of these cities are approximately the same as of Karakorum—late 14th century [7] when the Chinese army repeatedly raided the country and looted the cities though the aggressor was expelled each time. Karakorum was destroyed in 1380 and could never restore its previous magnificence. The long destructive wars waged by China continued from 1372 to 1422 ruining the cultural progress of Mongolia achieved during the imperial period. Mongolia fell back into dark Middle Ages till the second half of the 16th century, when her culture experienced Renaissance.

Renaissance

After the two centuries of cultural decline, Mongolia experienced Renaissance beginning in the second half of the 16th century. This was a period of relative peace free of foreign aggressions and introduction of Buddhism in the form of Gelugpa (3rd introduction of Buddhism). Altan Khan of Tumet founded city Hohhot in 1575 as a political and cultural centre of his holdings. Among the first Buddhist monasteries of Mongolia of this period was temple Thegchen Chonchor Ling in Khökh Nuur built by Altan Khan to memorise his 1577 meeting with Dalai Lama Sonam Gyatso.[8][9] Many temples were built in Hohhot during the period including Dazhao and Xilituzhao Temples.

In Khalkha, Abatai Khan founded the Erdene Zuu monastery in 1585 near the site of the ancient city Karakorum.[10] Although these first temples featured the Chinese architectural styles, the further development enriched the architecture of Mongolia with Tibetan, Indian and unique Mongolian styles.

The Mongolian style began with mobile temples. As they settled, they evolved into multi-angular and quadratic structures. As the roof was directly supported by the pillars and walls, it served also as the ceiling.[11]

G. Zanabazar, the first Bogdo Gegeen of Khalha, designed the architecture of many temples and monasteries in the traditional Mongolian style and supervised their construction. He succeeded merging the Oriental architecture with the designs of the Mongolian yurts and marquees. Especially the style of the Batu-Tsagaan Tsogchin temple of Urga designed by G. Zanabazar became a proto-type for the further development of the Mongolian style in architecture. It is a large marquee-shaped structure in which the four central columns support the main area of the roof. There are 12 columns in the middle row and the columns in the outer row are slightly higher. The total number of the columns is 108. This temple was designed to be expanded as necessary. Thus, it was originally 42 x 42 metres and was later expanded to 51 x 51 metres.[11]

The Indian style was most prominent in the design of stupas. Among the most famous stupas are Ikh Tamir, Altan Suburgan of Erdene Zuu, Jiran Khashir of Gandang and the mausoleums of Abatai Khan and Tüsheetu Khan Gombodorji.

Monasteries Khögnö Tarni (1600), Zaya-iin Khüree (1616), Baruun Khüree (1647) and Zaya-iin Khiid (1654) were built during this period.

Post-Renaissance

Building of magnificent temples in the traditions of the Renaissance period continued in the 18th, 19th and early 20th centuries. Ishbaljir (1709–1788) described the proportions of construction of buildings together with the proportions of human body in "Exquisite Flower Beads". Agvaanhaidav (1779–1838) described the process of building a Maitreya temple in "Maitreya Chapters Treasurous Mirror". Agvaanceren (1785–1849) wrote a book "The rules of building and repairing temples" teaching how to construct buildings and a book "Aahar shaahar" about maintenance and repairs of buildings.[11] Also translations of Kangyur were widely used by the Mongolian architects.

Monasteries Züün Huree (1711), Amarbayasgalant monastery (1727), Manjusri Hiid (1733) and others were built during this period. The mobile monastery Ihe Huree founded for Zanabazar settled at the present location of city Ulaanbaatar in 1779. The wall around Erdene Yuu monastery began to be built in 1734. It contains 108 stupas. The Temple of Boddhisattva Avalokiteshvara was built in 1911–1913 as symbol of the new independent Bogdo Khanate of Mongolia. The colossal statue of the Boddhisattva Avalokiteshvara Migjed Janraisig, that who opens the eyes of wisdom of sentient beings, symbolised enlightenment of the Mongolian people who had opened a new page in their history and stepped into the modern civilisation. In the beginning of the 20th century, there were around 800 monasteries throughout the country.

An interesting tendency in the beginning of the 20th century was an experiment of combining the traditional Asian architecture with the features of the Russian architectural style. Bogdo Khan had his winter palace built as a Russian "horomy". A legend holds that the Manchurian Khan was suspicious of the interest of Bogdo Gegeen VIII in the European culture. To calm down his suspicion, Bogdo Gegeen had a ganjir added to the top of the building. Another example of the combination of the Asian and Russian styles of architecture is the residence of Khanddorji Wang, a leader of the independence movement of 1911. The body of the building is designed as a Russian house while the top was designed in the 'baroque' Asian style. One of the first European buildings in Mongolia is the 2-storey building of Zanabazar Museum of Fine Arts. It was originally built as a trade centre in 1905.

-

19th-century painting of the Monastery of Sain Noyon Khan showing different styles of traditional architecture.

-

Temple at Amarbayasgalant monastery

-

Detail of 19th-century painting of Urga (Ulaanbaatar) also showing different styles of traditional architecture.

-

Avalokiteshvara Temple

-

Quadratic temple in the style of G. Zanabazar

-

Winter Palace of Bogdo-Khaan built in the traditional Russian style. It had a gold ganjir on the top.

-

Statue of Avalokiteśvara (Mongolian name: Migjid Janraisig), Gandantegchinlen Monastery. Tallest indoor statue in the world, 26.5-meter-high, 1996 rebuilt, (1913)

Revolutionary architecture

Despite the obvious progress, the Revolution also brought destruction of the traditional culture with demolition of over 800 monasteries and purge of thousands of lamas—carriers of the traditional intellectual culture including masters of traditional architecture. The development of the national culture of the Mongolians had to restart from zero.

Constructivism and Rationalism in architecture that flourished in the USSR also shot their roots in Mongolia, though in their most modest forms. The building of the Radio and Postal Communications Committee was the brightest example of constructivism with a pyramid-topped tower stressing its role in the town-building. This construction, unique in Mongolia, however was later disassembled. The other works constructed under the principles of constructivism and rationalism were the office of the Mongoltrans company, Ministry of Internal Affairs, and the Military Club built in the space, forms and composition order.[12]

Classicism and "mass-production"

The ensemble of Ulaanbaatar's downtown was designed by Soviet architects, developing the traditions of Classicism under the conditions of Socialism (Stalinist architecture). The buildings of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the State University, the House of the Government, the Opera House, the State Library and many other public buildings that were constructed during this period demonstrate the magnificence and elegance of European Classicism.

The Mongolian architects worked to creatively combine this neo-Classicism with the traditional features of Mongolian architecture. The development of Ulaanbaatar's downtown continued at the initiative of B. Chimed who is the architect of the Drama Theater, the Natural History Museum and the Ulaanbaatar Hotel. The overall design of the Drama Theatre implemented in neo-Classicism employs the quadratic plane and double-tier marquee roof of the Mongolian architecture. These works evidence his creative search for developing the indigenous traditions in the contemporary architecture. This direction was followed by other architects, e.g. in the Urt Tsagaan (Tourists Walk) and House of Health Education (today used by the Ministry of Health) by B. Dambiinyam and the Astronomical Observatory, State University Building #2, and Meteorology Building by A. Hishigt, which cannot be mistaken for European buildings.[12]

From the 1960s, the design of architecture was dictated by requirements of economy and mass-production under the influence of the Nikita Khrushchev and Leonid Brezhnev eras in the Soviet Union. At the same time, the early 1960s were characterised by increased Soviet and Chinese investment due to their competition for greater influence in Mongolia. Such a competition resulted in an accelerated development of the country. Thus both the older districts south of the river Dundgol and the Peace bridge were built by Chinese workers.

The architecture of the 1960s and 1970s presents the monotony of 4-, 5-, and 9-storey apartment blocks with simple rectangular shapes dictated by the need of cheap and speedy construction. The looks of cities became increasingly boring and dull. The hostility between the USSR and PRC forced Mongolia to side with only one of the two and Mongolia allied with the USSR. This external political situation led to an immensely increased influx of Soviet investment. Apartment districts were intensively built in all directions around Ulaanbaatar, including the area to the south of the Dundgol river, often by Soviet soldiers. Completely new cities were founded in Darkhan, Erdenet and Baganuur during this period.

The visit of L. Brezhnev in 1974 was followed by a donation of the modern housing massif in what is now Bayangol district. This massif consists of extensive 9-storey apartment blocks decorated with five V-shaped 12-storey buildings located along the Ayush street, giving it a resemblance of the famous Kalinin Avenue in the centre of Moscow. This street is today the busiest shopping mall in the capital of Mongolia. Although presenting little artistic interest, the Socialist apartment districts were comfortable, spacious environments for family life with safe playgrounds for children. The entire cities were designed for pedestrians. In Darkhan and Erdenet, the industries are separated from the living parts by a mountain. A pride of this epoch was the Wedding Palace in Ulaanbaatar. Designed in the Mongolian style, it was in a beautiful harmony with the Choijim Lama Monastery at its northwest. The entire area of the Wedding Palace and the Monastery were a unique architectural symphony which was unfortunately disturbed by a cacophony of business buildings that chaotically emerged in the early 21st century.

The monotony of the cities was criticised at 4 successive congresses of the Mongolian Association of Architects since 1972; however, no significant improvement was achieved.[12] The beginning of the 1980s brought new public buildings such as Museum of Lenin and the Yalalt cinema (nowadays Tengis) which added national features to the Socialist designs. The Ethnographical Museum located in the centre of Ulaanbaatar's amusement park was designed as an imaginary Mongolian castle surrounded by walls on an island in the middle of an artificial lake. The winter house of the international children's Nairamdal camp was designed as large ocean ship travelling in the sea of mountains. One of the largest monuments of the Socialist period is the National Palace of Culture. Though demonstrating some shapes of the Mongolian architecture, the basic design of the palace is found in the capitals of many former Socialist countries.

With a vision of complete replacement of yurts with apartment blocks in future, the yurt districts were seen as a temporary and transient form of housing. Therefore, during Socialism the state made no or little effort (except for bathhouses) to develop the yurt districts, which became peculiar shanty-towns of Mongolia.

Modern period

Perestroika and transition to the democratic values induced two tendencies: first is the interest to the traditional culture and history and second is the interest to free liberated thinking in the arts and architecture. Virtually the entire population of Mongolia made donations to the repairs of the Chenrezig temple in the Gandan Tegchinling monastery and to the re-casting of the giant statue of Boddhisattva Avalokiteshvara. A group of artists and architects led by actor Bold, an enthusiast of traditional architecture, developed an ambitious project to change Ulan Bator into a profoundly Asian city. They began constructing gates and shades in the traditional style in the Street of Revolutionaries and other streets as well as in the amusement park. The implementation of their project stopped at the beginning of the severe economic crisis. Nevertheless, the Buddhist sangha of Mongolia continued restoration of the monasteries and establishing new ones.

Modern architecture eventually took its place as the economy began recovering from the crisis. The completion of the construction of the tall glass building of Ardiin Bank (nowadays hosting Ulaanbaatar Bank) as well as of the giant glass building complex of Chinggis Khan hotel in the second half of 1990s marked the beginning of the new age in the Mongolian architecture.

Among the constructions of this period, the Bodhi Tower of 2004 represents an interesting solution. It consists of 2 parts. The part facing the Sükhbaatar Square is a 4-storey building implemented in the style of Classicism and it perfectly harmonises with the architectural ensemble of the 1950s. A highrise tower facing the Sükhbaatar Square would be out of space. Instead the modern style tower, the other part of the building, faces the backstreet (a similar principle is also observed with the National Palace of Culture of the previous period). Another work of this period is the Narantuul tower, recognised as one of the most elegant designs in Ulaanbaatar. The majestic hotel complex Mongol Castle in Gachuurt region of Ulaanbaatar reveals an interest of the authors in the historical past. With a Silver Tree fountain at the centre, it creates for visitors an impression of traveling in the palace of the Great Khan in ancient Karakorum.

Prime Minister Tsakhiagiin Elbegdorj appointed a working group of professionals to develop a project to build a new city at the site of the ancient capital Karakorum. According to him, the new Karakorum was to be designed to be an exemplary city with a vision of becoming the capital of Mongolia. After his resignation and appointment of Miyeegombyn Enkhbold as Prime Minister, this project was abandoned.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Architecture of Mongolia. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Buildings in Mongolia. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Culture of Mongolia. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Architecture of the Yuan Dynasty. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Monasteries in Mongolia. |

- List of historical cities and towns of Mongolia

- Khanbaliq

- Gandantegchinlen Khiid Monastery

- Manjusri Monastery

- National Academic Theatre of Opera and Ballet of Mongolia

- Temple of the Five Pagodas

- Noin-Ula

- Orkhon Valley

- Artificial Lake Castle

- Mongol Castle

- Ugsarmal bair

- International Commercial Center

- Ulaanbaatar railway station

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 Chultem, N. (1984). Искусство Монголии. Moscow.

- ↑ "Cultural Heritage of Mongolia". Indiana University. Archived from the original on 2007-07-02. Retrieved 2007-07-07.

- ↑ "The Xiongnu". Ulrich Theobald. Archived from the original on 29 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-22.

- ↑ Rudenko, S. I. (1962). Культура хуннов и ноин-улинские курганы. Moscow.

- 1 2 3 Maidar, D. (1971). Архитектура и градостоительство Монголии. Moscow.

- ↑ Kiselev S. V. and Merpert N. Y (1965). Железные и чугунные изделия из Кара-Корума. Moscow.

- ↑ Kiselev, S. V. (1965). "Город на реке Хир-Хира" and "Дворец в Кондуе"--в сборнике Древнемонгольские города. Moscow.

- ↑ Rosary of White Lotuses.

- ↑ "Zanabazar". Archived from the original on 19 October 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- ↑ "Zanabazar". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- 1 2 3 Oyunbileg, Z. (1990). Монголд уран барилга хөгжиж байсан нь. Journal "Дүрслэх урлаг, уран барилга" ("Fine Arts and Architecture") 1990-1. Ulaanbaatar.

- 1 2 3 Odon, S. (1990). Хүний амьдралын орчинг архитектурт хамааруулахын учир. Journal "Дүрслэх урлаг, уран барилга" ("Fine Arts and Architecture") 1990-2. Ulaanbaatar.