Autoimmune hepatitis

| Autoimmune hepatitis | |

|---|---|

|

Micrograph showing a lymphoplasmacytic interface hepatitis -- the characteristic histomorphologic finding of autoimmune hepatitis. Liver biopsy. H&E stain. | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | gastroenterology, hepatology |

| ICD-10 | K75.4 |

| ICD-9-CM | 571.42 |

| DiseasesDB | 1150 |

| MedlinePlus | 000245 |

| eMedicine | med/366 |

| MeSH | D019693 |

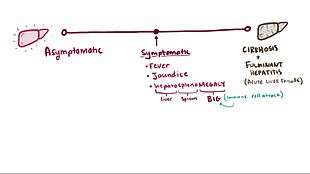

Autoimmune hepatitis, formerly called lupoid hepatitis, is a chronic, autoimmune disease of the liver that occurs when the body's immune system attacks liver cells causing the liver to be inflamed. Common initial symptoms include fatigue or muscle aches or signs of acute liver inflammation including fever, jaundice, and right upper quadrant abdominal pain. Individuals with autoimmune hepatitis often have no initial symptoms and the disease is detected by abnormal liver function tests.[1]

Anomalous presentation of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class II on the surface of liver cells, possibly due to genetic predisposition or acute liver infection, causes a cell-mediated immune response against the body's own liver, resulting in autoimmune hepatitis. This abnormal immune response results in inflammation of the liver, which can lead to further symptoms and complications such as fatigue and cirrhosis.[2] The disease may occur in any ethnic group and at any age, but is most often diagnosed in patients between age 40 and 50.[3]

Signs and symptoms

People may present with signs of chronic liver disease (abnormal liver function tests, fatigue, aches) or acute hepatitis (fever, jaundice, right upper quadrant abdominal pain).

"Autoimmune hepatitis usually occurs in women (70 %) between the ages of 15 and 40. Although the term "lupoid" hepatitis was originally used to describe this disease, patients with systemic lupus erythematosus do not have an increased incidence of autoimmune hepatitis and the two diseases are distinct entities. Patients usually present with evidence of moderate to severe hepatitis with elevated serum ALT and AST activities in the setting of normal to marginally elevated alkaline phosphatase and gamma-glutamyltranspeptidase activities. The patient will sometimes present with jaundice, fever and right upper quadrant pain and occasionally systemic symptoms such as arthralgias, myalgias, polyserositis and thrombocytopenia. Some patients will present with mild liver dysfunction and have only laboratory abnormalities as their initial presentation. Others will present with severe hepatic dysfunction."[4]

Cause

60% of patients have chronic hepatitis that may mimic viral hepatitis, but without serologic evidence of a viral infection. The disease usually affects women and is strongly associated with anti-smooth muscle autoantibodies.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis is best achieved with a combination of clinical, laboratory and histological findings after excluding other etiological factors (e.g. viral, hereditary, metabolic, cholestatic, and drug-induced diseases).

A number of specific antibodies found in the blood (antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-smooth muscle antibody (SMA), liver/kidney microsomal antibody (LKM-1, LKM-2, LKM-3), anti soluble liver antigen and liver–pancreas antigen (SLA/LP) and anti-mitochondrial antibody (AMA)) are of use, as is finding an increased Immunoglobulin G level. However, the diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis always requires a liver biopsy.

Expert opinion has been summarized by the International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group, which has published criteria which utilize clinical and laboratory data that can be used to help determine if a patient has autoimmune hepatitis.[5] A calculator based on those criteria is available online.[6]

Overlapping presentation with primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis has been observed.[7]

Classification

Four subtypes are recognised, but the clinical utility of distinguishing subtypes is limited.

- positive ANA and SMA,[8] elevated immunoglobulin G (classic form, responds well to low dose steroids);

- positive LKM-1 (typically female children and teenagers; disease can be severe), LKM-2 or LKM-3;

- positive antibodies against soluble liver antigen[9] (this group behaves like group 1)[10] (anti-SLA, anti-LP)

- no autoantibodies detected (~20%) (of debatable validity/importance)

Treatment

Treatment may involve the prescription of immunosuppressive glucocorticoids such as prednisone, with or without azathioprine, and remission can be achieved in up to 60–80% of cases, although many will eventually experience a relapse.[11] Budesonide has been shown to be more effective in inducing remission than prednisone, and result in fewer adverse effects.[12] Those with autoimmune hepatitis who do not respond to glucocorticoids and azathioprine may be given other immunosuppressives like mycophenolate, ciclosporin, tacrolimus, methotrexate, etc. Liver transplantation may be required if patients do not respond to drug therapy or when patients present with fulminant liver failure.[13]

Prognosis

Autoimmune hepatitis is not a benign disease. Despite a good initial response to immunosuppression, recent studies suggest that the life expectancy of patients with autoimmune hepatitis is lower than that of the general population.[14][15][16] Additionally, presentation and response to therapy appears to differ according to race. For instance, African Americans appear to present with a more aggressive disease that is associated with worse outcomes.[17][18]

Epidemiology

Autoimmune hepatitis has an incidence of 1-2 per 100,000 per year, and a prevalence of 10-20/100,000. As with most other autoimmune diseases, it affects women much more often than men (70%).[19] Liver enzymes are elevated, as may be bilirubin.

History

Autoimmune hepatitis was previously called "lupoid" hepatitis. It was originally described in the early 1950s.

Most patients do have an associated autoimmune disorder such as systemic lupus erythematosus. Thus, its name was previously lupoid hepatitis.

Because the disease has multiple different forms, and is not always associated with systemic lupus erythematosus, lupoid hepatitis is no longer used. The current name at present is autoimmune hepatitis (AIH).

References

- ↑ Czaja, AJ (May 2004). "Autoimmune liver disease.". Current opinion in gastroenterology. 20 (3): 231–40. doi:10.1097/00001574-200405000-00007. PMID 15703647.

- ↑ National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse. "Digestive Disease: Autoimmune Hepatitis". Archived from the original on 15 September 2010. Retrieved October 9, 2010.,

- ↑ Manns, MP; Czaja, AJ; Gorham, JD; Krawitt, EL; Mieli-Vergani, G; Vergani, D; Vierling, JM; American Association for the Study of Liver, Diseases (June 2010). "Diagnosis and management of autoimmune hepatitis.". Hepatology (Baltimore, Md.). 51 (6): 2193–213. doi:10.1002/hep.23584. PMID 20513004.

- ↑ Krawitt, E. L. (1996). "Autoimmune hepatitis". New England Journal of Medicine. 334 (14): 897–903. doi:10.1056/NEJM199604043341406. PMID 8596574.

- ↑ Alvarez F, Berg PA, Bianchi FB, et al. (November 1999). "International Autoimmune Hepatitis Group Report: review of criteria for diagnosis of autoimmune hepatitis". J. Hepatol. 31 (5): 929–38. doi:10.1016/S0168-8278(99)80297-9. PMID 10580593. Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ↑ "Autoimmune Hepatitis Calculator". Retrieved 2008-05-09.

- ↑ Washington MK (February 2007). "Autoimmune liver disease: overlap and outliers". Mod. Pathol. 20 Suppl 1: S15–30. doi:10.1038/modpathol.3800684. PMID 17486048.

- ↑ Bogdanos DP, Invernizzi P, Mackay IR, Vergani D (June 2008). "Autoimmune liver serology: Current diagnostic and clinical challenges". World J. Gastroenterol. 14 (21): 3374–3387. doi:10.3748/wjg.14.3374. PMC 2716592

. PMID 18528935.

. PMID 18528935. - ↑ "autoimmune hepatitis".

- ↑ "Medscape & eMedicine Log In".

- ↑ Krawitt EL (January 1994). "Autoimmune hepatitis: classification, heterogeneity, and treatment". Am. J. Med. 96 (1A): 23S–26S. doi:10.1016/0002-9343(94)90186-4. PMID 8109584.

- ↑ Manns, MP; Strassburg, CP (2011). "Therapeutic strategies for autoimmune hepatitis.". Digestive diseases (Basel, Switzerland). 29 (4): 411–5. doi:10.1159/000329805. PMID 21894012.

- ↑ Stephen J Mcphee, Maxine A Papadakis. Current medical diagnosis and treatment 2009 page.596

- ↑ Hoeroldt, Barbara; McFarlane, Elaine; Dube, Asha; Basumani, Pandurangan; Karajeh, Mohammed; Campbell, Michael J.; Gleeson, Dermot (2011). "Long-term Outcomes of Patients With Autoimmune Hepatitis Managed at a Nontransplant Center". Gastroenterology. 140 (7): 1980–1989. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.02.065. ISSN 0016-5085.

- ↑ Ngu, Jing Hieng; Gearry, Richard Blair; Frampton, Chris Miles; Stedman, Catherine A.M. (2013). "Predictors of poor outcome in patients with autoimmune hepatitis: A population-based study". Hepatology. 57 (6): 2399–2406. doi:10.1002/hep.26290. ISSN 0270-9139.

- ↑ Ngu, Jing Hieng; Gearry, Richard Blair; Frampton, Chris Miles; Malcolm Stedman, Catherine Ann (2012). "Mortality and the risk of malignancy in autoimmune liver diseases: A population-based study in Canterbury, New Zealand". Hepatology. 55 (2): 522–529. doi:10.1002/hep.24743. ISSN 0270-9139.

- ↑ Lim, Kie N.; Casanova, Roberto L.; Boyer, Thomas D.; Bruno, Christine Janes (2001). "Autoimmune hepatitis in African Americans: presenting features and response to therapy". The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 96 (12): 3390–3394. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.05272.x. ISSN 0002-9270.

- ↑ Verma, Sumita; Torbenson, Michael; Thuluvath, Paul J. (2007). "The impact of ethnicity on the natural history of autoimmune hepatitis". Hepatology. 46 (6): 1828–1835. doi:10.1002/hep.21884. ISSN 0270-9139.

- ↑ "Autoimmune Hepatitis".