Autonomous sensory meridian response

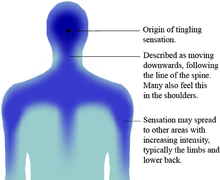

Autonomous sensory meridian response (ASMR) is a euphoric experience characterized by a static-like or tingling sensation on the skin that typically begins on the scalp and moves down the back of the neck and upper spine, precipitating relaxation. It has been compared with auditory-tactile synesthesia.[1][2] Autonomous sensory meridian response (ASMR) signifies the subjective experience of 'low-grade euphoria' characterized by 'a combination of positive feelings, relaxation, and a distinct static-like tingling sensation on the skin'. It typically begins 'on the scalp' before moving 'down the spine' to the base of the neck, sometimes spreading 'to the back, arms and legs as intensity increases', most commonly triggered by specific acoustic, visual and digital media stimuli, and less commonly by intentional attentional control.[3][4]

Overview

Origins of the name

The term 'autonomous sensory meridian response' (ASMR) was coined on 25 February 2010 by Jennifer Allen, a cybersecurity professional residing in New York[5] in the introduction to a Facebook Group she founded entitled the 'ASMR Group'.[6]

Prior to the subsequent social consensus that led to what is now the ubiquitous adoption of that term, other names were proposed and discussed at a number of locations including the Steady Health forum, the 'Society of Sensationalists' Yahoo! Group, and the 'Unnamed Feeling' Blog.

Proposed formal names included 'Attention Induced Head Orgasm', 'Attention Induced Euphoria', and 'Attention Induced Observant Euphoria'; whilst colloquial terms in usage included 'brain massage', 'head tingle', brain tingle', 'spine tingle', and 'brain orgasm'.[7][8][9][10][11][12]

Whilst many colloquial and formal terms used and proposed between 2007 and 2010 included reference to 'orgasm', there was during that time a significant majority objection to its use among those active in online discussions, many of whom have continued to persist in differentiating the euphoric and relaxing nature of ASMR from sexual arousal.[12][13] However, by 2015, a division had occurred within the ASMR community over the subject of sexual arousal, with some creating videos categorized as ASMRotica, which are deliberately designed to be sexually stimulating.[14][15]

The initial consensus among the 'ASMR Community' was that the name should not pose a high risk of the phenomenon being perceived as sexual. Given that consensus, Allen proposed 'autonomous sensory meridian response' (ASMR). Allen chose the words intending or assuming them to have the following specific meanings:

- Autonomous – spontaneous, self-governing, within or without control

- Sensory – pertaining to the senses or sensation

- Meridian – signifying a peak, climax, or point of highest development

- Response – referring to an experience triggered by something external or internal

Allen chose the word 'meridian' as 'a kinder way of saying 'orgasmic' or 'peak', indicating a non-sexual experience comparable in pleasurable intensity to orgasm.[16]

The term 'autonomous sensory meridian response' and its initialism 'ASMR' were adopted by both the community of contributors to online discussions, and those reporting and commentating on the phenomenon.

The sensation and how it is triggered

The sensation

The subjective experience, sensation, and perceptual phenomenon now widely identified by the term 'autonomous sensory meridian response' is described by some of those susceptible to it as 'akin to a mild electrical current…or the carbonated bubbles in a glass of champagne'.[17]

The triggers

ASMR is usually precipitated by stimuli referred to as 'triggers'.[17] ASMR triggers, which are most commonly acoustic and visual, may be encountered through the interpersonal interactions of daily life. Additionally, ASMR is often triggered by exposure to specific audio and video. Such media may be especially made with the specific purpose of triggering ASMR, or originally created for other purposes and later discovered to be effective as a trigger of the experience.[3]

Stimuli that can trigger ASMR, as reported by those who experience it, include the following:

- Listening to a softly spoken or whispering voice

- Listening to quiet, repetitive sounds resulting from someone engaging in a mundane task such as turning the pages of a book

- Watching somebody attentively execute a mundane task such as preparing food

- Receiving altruistic tender personal attention

- Initiating the stimulus through conscious manipulation without the need for external video or audio triggers

Furthermore, watching and listening to an audiovisual recording of a person performing or simulating the above actions and producing their consequent and accompanying sounds is sufficient to trigger ASMR for the majority of those who report susceptibility to the experience.[18][19][20][21]

Whispering triggers

Psychologists Nick Davis and Emma Barrat discovered that whispering was an effective trigger for 75% of the 475 subjects who took part in an experiment to investigate the nature of ASMR;[3] and that statistic is reflected in the popularity of intentional ASMR videos that comprise someone speaking in a whispered voice.[22][23][24]

Acoustic triggers

Many of those who experience ASMR report that some specific non-vocal ambient noises are also effective triggers of ASMR, including those produced by fingers scratching or tapping a surface, the crushing of eggshells, the crinkling and crumpling of a flexible material such as paper, writing, and a person or animal eating. Many intentional ASMR videos posted to YouTube capture a single person performing these actions and their subsequent sounds.[25][26]

Personal attention role play triggers

In addition to the effectiveness of specific acoustic stimuli, many subjects report that ASMR is triggered by the receipt of tender personal attention, often comprising combined physical touch and vocal expression, such as when having their hair cut, nails painted, ears cleaned, or back massaged, whilst the service provider speaks quietly to the recipient. Furthermore, many of those who have experienced ASMR during these and other comparable encounters with a service provider report that watching an 'ASMRtist' simulate the provision of such personal attention, acting directly to camera as if the viewer were the recipient of a simulated service, is sufficient to trigger it.[4][27][28]

Psychologists Nick Davis and Emma Barrat discovered that personal attention was an effective trigger for 69% of the 475 subjects who participated in a study conducted at Swansea University, second in popularity only to whispering.[3]

Clinical role play triggers

Among the category of intentional ASMR videos that simulate the provision of personal attention is a subcategory of those specifically depicting the 'ASMRtist' providing clinical or medical services, including routine general medical examinations. The creators of these videos make no claims to the reality of what is depicted, and the viewer is intended to be aware that they are watching and listening to a simulation, performed by an actor. Nonetheless, many subjects attribute therapeutic outcomes to these and other categories of intentional ASMR videos, and there are voluminous anecdotal reports of their effectiveness in inducing sleep for those susceptible to insomnia, and assuaging a range of symptoms including those associated with depression, anxiety, and panic attacks.[29][30][31]

In the first peer-reviewed article on ASMR, published in Perspectives in Biology during the summer of 2013, Nitin Ahuja then a medical student at the University of Virginia, invited conjecture on whether the receipt of simulated medical attention might have some tangible therapeutic value for the recipient, comparing the purported positive outcome of clinical role play ASMR videos with the themes of the novel Love in the Ruins by author and physician Walker Percy, published in 1971.[4]

The story follows Tom More, a psychiatrist living in a dystopian future who develops a device called the Ontological Lapsometer that, when traced across the scalp of a patient, detects the neurochemical correlation to a range of disturbances. In the course of the novel, More admits that the 'mere application of his device' to a patient's body 'results in the partial relief of his symptoms.'[32]

Ahuja alleges that through the character of Tom More, as depicted in Love in the Ruins, Percy 'displays an intuitive understanding of the diagnostic act as a form of therapy unto itself'. Ahuja asks whether similarly, the receipt of simulated personal clinical attention by an actor in an ASMR video might afford the listener and viewer some relief.[33]

Background and history

Contemporary history

The contemporary history of ASMR began on 19 October 2007 when a 21-year-old registered user of a discussion forum for health-related subjects at a website called 'Steady Health',[34] with the username 'okaywhatever', submitted a post in which they described having experienced a specific sensation since childhood, comparable to that stimulated by tracing fingers along the skin, yet often triggered by seemingly random and unrelated non-haptic events, such as 'watching a puppet show' or 'being read a story'.[35]

Replies to this post, which indicated that a significant number of others experienced the sensation to which 'okaywhatever' referred, also in response to witnessing mundane events, precipitated the formation of a number of web-based locations intended to facilitate further discussion and analysis of the phenomenon for which there was plentiful anecdotal accounts,[22][36][37] yet no consensus-agreed name nor any scientific data or explanation.[29]

These included a Yahoo! Group called 'The Society of Sensationalists', founded on 12 December 2008 by a user named 'Ryan, AKA M?stery';[38] a blog at Blogspot.com called 'The Unnamed Feeling', launched on 13 February 2010 by Andrew MacMuiris;[39] an ASMR Facebook Group founded on 25 February 2010 by Jennifer Allen;[6] a Subreddit forum created by an individual with the username ' MrStonedOne' on 28 February 2011;[40] and a number of other web locations that facilitate user interaction.[41][42][43][44]

Earlier history

Austrian writer Clemens J. Setz suggests that a passage from the novel Mrs. Dalloway authored by Virginia Woolf and published in 1925, describes something distinctly comparable.[45][46] In the passage from Mrs. Dalloway cited by Setz, a nursemaid speaks to the man who is her patient 'deeply, softly, like a mellow organ, but with a roughness in her voice like a grasshopper’s, which rasped his spine deliciously and sent running up into his brain waves of sound'.[47]

According to Setz, this citation generally alludes to the effectiveness of the human voice and soft or whispered vocal sounds specifically as a trigger of ASMR for many of those who experience it, as demonstrated by the responsive comments posted to YouTube videos that depict someone speaking softly or whispering, typically directly to camera.[22][23][24]

Evolutionary history

Nothing is known about whether or not there are any evolutionary origins to ASMR because the perceptual phenomenon is yet to be clearly identified as having biological correlates. Notwithstanding, a significant majority of descriptions of ASMR by those who experience it compare the sensation to that precipitated by receipt of tender physical touch, providing examples such as having their hair cut or combed. This has precipitated conjecture that ASMR might be related to the act of grooming.[48][49][50]

For example, David Huron, Professor in the School of Music at Ohio State University, states that the 'ASMR effect' is 'clearly strongly related to the perception of non-threat and altruistic attention' and has a 'strong similarity to physical grooming in primates' who 'derive enormous pleasure (bordering on euphoria) when being groomed by a grooming partner' 'not to get clean, but rather to bond with each other.'[25]

The two categories of the 'ASMR' experience

Whilst little scientific research has been conducted into potential neurobiological correlates to the perceptual phenomenon known as 'autonomous sensory meridian response' (ASMR), with a consequent dearth of data with which to either explain or refute its physical nature, there is voluminous anecdotal literature comprising personal commentary and intimate disclosure of subjective experiences distributed across forums, blogs, and YouTube comments by hundreds of thousands of people. Within this literature, in addition to the original consensus that ASMR is euphoric but non-sexual in nature, a further point of continued majority agreement within the community of those who experience it is that they fall into two broad categories of subjects.[35][38][40][51]

One category depends upon external triggers in order to experience the localized sensation and its associated feelings, which typically originates in the head, often reaching down the neck and sometimes the upper back. The other category can intentionally augment the sensation and feelings through attentional control, without dependence upon external stimuli, or 'triggers', in a manner compared by some subjects to their experience of meditation.[52]

ASMR and meditation

Several scientists have posited that there may be similarities between ASMR and meditative or contemplative practice. For example, in May 2013 psychiatrist Michael Yasinski was reported to have said that ASMR may be similar to meditation in the way it helps individuals 'focus' and 'relax' helping to 'shut down' 'parts of the brain' 'responsible for stress and anxiety'. Subsequently, in June 2014, Carl W. Bazil, Professor of Neurology at Columbia University Medical Center and director of its Sleep Disorders Center,[53] suggested that ASMR videos 'seem to be a variation on finding ways to shut your brain down' comparable to 'guided imagery, progressive relaxation, hypnosis and meditation'.[30][54][55]

Meanwhile, the first peer-reviewed article on ASMR based on a scientific experiment, conducted at Swansea University by psychologists Nick Davis and Emma Barratt,[3] suggests that the subjective experience of ASMR might compare to the state of 'flow' identified by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi as the condition of fully concentrating on and being completely absorbed in the present activity or situation to such a degree that nothing else seems to matter.[56]

ASMR media

ASMR videos

The most popular source of stimuli reported by subjects to be effective in triggering ASMR is video; and the most popular source of such media is YouTube. Videos reported to be effective in triggering ASMR fall into two categories, identified and named by the community as 'Intentional' and 'Unintentional'. Intentional media is created by those known within the community as 'ASMRtists' with the purpose of triggering ASMR in viewers and listeners. Unintentional media is that made for other purposes, often before attention was drawn to the phenomenon in 2007, but which some subjects discover to be effective in triggering ASMR.[40][57] One of the most popular examples of unintentional media as several journalists have noted is of famed painter Bob Ross and his videos on YouTube triggering the effect on many of the viewers.[58][59]

Binaural recording

Some ASMR video creators use binaural recording techniques to simulate the acoustics of a three dimensional environment, reported to elicit in viewers and listeners the experience of being in close proximity to actor and vocalist.[60]

Viewing and hearing such ASMR videos that comprise ambient sound captured through binaural recording has been compared to the reported effect of listening to binaural beats, which are also alleged to precipitate pleasurable sensations and the subjective experience of calm and equanimity.[61]

Binaural recordings are made specifically to be heard through headphones rather than loudspeakers. When listening to sound through loudspeakers, the left and right ear can both hear the sound coming from both speakers. By distinction, when listening to sound through headphones, the sound from the left earpiece is audible only to the left ear, and the sound from the right ear piece is audible only to the right ear. When producing binaural media, the sound source is recorded by two separate microphones, placed at a distance comparable to that between two ears, and they are not mixed, but remain separate on the final medium, whether video or audio.[62]

Listening to a binaural recording through headphones simulates the binaural hearing by which people listen to live sounds. For the listener, this experience is characterized by two perceptions. Firstly, the listener perceives being in close proximity to the performers and location of the sound source. Secondly, the listener perceives what is often reported as a three dimensional sound.[60]

Clinical implications

There are no scientific data nor any clinical trials from which to deduce evidence that might support or refute any clinical benefits or dangers of ASMR, with claims to therapeutic efficacy remaining based on voluminous personal anecdotal accounts by those who attribute the positive effect on anxiety, depression, and insomnia to ASMR video media.[36][63][64]

Amer Khan, a physician who practices sleep medicine at the Sutter Neuroscience Institute, has advised that watching ASMR videos as a means to treat insomnia may not be the best method by which to induce high-quality sleep, as it could become a habit comparable to dependence on a white noise machine.[65]

This point of view is contradicted by Carl W. Bazil, Professor of Neurology at Columbia University Medical Center and director of its Sleep Disorders Center,[53] who suggests that ASMR videos may provide ways to 'shut your brain down' that are a variation of other methods, including guided imagery, progressive relaxation, hypnosis and meditation', of potential particular benefit for those with insomnia, whom he describes as being in a 'hyper state of arousal'.[30]

Research and commentary

Peer-reviewed articles

Several peer-reviewed articles about ASMR have been published.

The first, by the medical student Nitin Ahuja, is titled It Feels Good to Be Measured: clinical role-play, Walker Percy, and the tingles. It was published in Perspectives in Biology and Medicine during 2013 and focused on a conjectural cultural and literary analysis.[33]

Another article, published in the journal Television and New Media in November 2014, is by Joceline Andersen, a doctoral student in the Department of Art History and Communication Studies at McGill University,[66] who suggested that ASMR videos comprising whispering 'create an intimate sonic space shared by the listener and the whisperer'. Andersen's article proposes that the pleasure jointly shared by both an ASMR video creator and its viewers might be perceived as a particular form of 'non-standard intimacy' by which consumers pursue a form of pleasure mediated by video media. Andersen suggests that such pursuit is private yet also public or publicized through the sharing of experiences via online communication with others within the 'whispering community'.[67]

Another article, 'Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR): a flow-like mental state', by Nick Davis and Emma Barratt, lecturer and post-graduate researcher respectively in the Department of Psychology at Swansea University, was published in PeerJ. This article aimed to 'describe the sensations associated with ASMR, explore the ways in which it is typically induced in capable individuals…to provide further thoughts on where this sensation may fit into current knowledge on atypical perceptual experiences…and to explore the extent to which engagement with ASMR may ease symptoms of depression and chronic pain '[3] The paper was based on a study of 245 men, 222 women, and 8 individuals of non-binary gender, aged from 18 to 54 years, all of whom had experienced ASMR, and regularly consumed ASMR media, from which the authors concluded and suggested that 'given the reported benefits of ASMR in improving mood and pain symptoms…ASMR warrants further investigation as a potential therapeutic measure similar to that of meditation and mindfulness.'

An article titled An examination of the default mode network in individuals with autonomous sensory meridian response (ASMR) [68] by Stephen D. Smith, Beverley Katherine Fredborg, and Jennifer Kornelsen, looked at the default mode network (DMN) in individuals with ASMR. The study, which used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), concluded that there were significant differences in the DMN of individuals who have ASMR as compared to a control group without ASMR.

Graduate theses

Prior to the publication of these three peer-reviewed articles, in May 2013, Bryson Lochte, an undergraduate in the Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences at Dartmouth College, submitted his final thesis entitled Touched Through a Screen: Putative Neural Correlates of Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response[69] based on studies conducted at the college's Brain Imaging Laboratory[70] supervised by Professor William M. Kelley.[71]

The study used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to investigate the effects of two categories of popular ASMR videos on the brain, using 18 subjects. The first category depicted an ASMRtist giving direct attention to the camera; the second type showed two actors interacting from a third person perspective. Non-ASMR videos were used as a control. Results showed that the first category precipitated increased activation in areas of the brain 'associated with self-referential and empathetic thought'; the second category 'caused activity in the mirror neuron system'; and both categories instigated 'activation of the somatosensory regions'. Based on these results, Lochte suggests that the first category of ASMR videos, in which the ASMRtist speaks and looks directly to camera, 'generate cognitive engagement indicative of actual human interaction'.

Subsequently, in 2014, Kathryn Durkin completed a thesis based on comparing ASMR with previously studied relaxation techniques, under the supervision of Randolph Lee, Associate Professor of Psychology at Trinity College.[72][73]

Most recently, Amy Huffenberger completed a thesis at the College of Wooster based on an investigation into whether ASMR increased the cognitive ability of facial recognition.[74]

Scientific commentary

A number of scientists have published or made public their reaction to and opinions of ASMR.

On 12 March 2012, Steven Novella, Director of General Neurology at the Yale School of Medicine and an active contributor to widely reported and academically cited discussion and debate on topics related to neurology and scientific skepticism, published a post about ASMR on Neurologica, a blog dedicated to his writings on neuroscience, skepticism, and critical thinking. In it, Novella says that he always starts his investigations of such phenomena by asking whether or not it is real. Regarding ASMR, Novella says "in this case, I don't think there is a definitive answer, but I am inclined to believe that it is. There are a number of people who seem to have independently experienced and described" it with "fairly specific details. In this way it's similar to migraine headaches – we know they exist as a syndrome primarily because many different people report the same constellation of symptoms and natural history." Novella tentatively posits the possibilities that ASMR might be either a type of pleasurable seizure, or another way to activate the "pleasure response". However, Novella draws attention to the lack of scientific investigation into ASMR, suggesting that functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and transcranial magnetic stimulation technologies should be used to study the brains of people who experience ASMR in comparison to people who do not, as a way of beginning to seek scientific understanding and explanation of the phenomenon.[75][76]

Four months after Novella's blog post, Tom Stafford, a lecturer in psychology and cognitive sciences at the University of Sheffield, was reported to have said that ASMR "might well be a real thing, but it's inherently difficult to research…something like this that you can't see or feel" and "doesn't happen for everyone". Stafford compares the current status of ASMR with development of attitudes toward synesthesia, which he says "for years...was a myth, then in the 1990s people came up with a reliable way of measuring it."[77]

Comparisons and associations with other phenomena

Comparison with synesthesia

Integral to the subjective experience of ASMR is a localized tingling sensation that many describe as similar to being gently touched, but which is stimulated by watching and listening to video media in the absence of any physical contact with another person.

These reports have precipitated comparison between ASMR and synesthesia – a condition characterized by the excitation of one sensory modality by stimuli that normally exclusively stimulates another, as when the hearing of a specific sound induces the visualization of a distinct color, a type of synesthesia called chromesthesia. Thereby, people with other types of synesthesia report for example 'seeing sounds' in the case of auditory-visual synesthesia, or 'tasting words' in the case of lexical-gustatory synesthesia.[78][79][80][81][82]

In the case of ASMR, many report the perception of 'being touched' by the sights and sounds presented on a video recording, comparable to visual-tactile and auditory-tactile synesthesia.[83]

Comparison with misophonia

Some commentators and members of the ASMR community have sought to relate ASMR to misophonia, which literally means the 'hatred of sound', but manifests typically as 'automatic negative emotional reactions to particular sounds – the opposite of what can be observed in reactions to specific audio stimuli in ASMR'.[3]

For example, those who suffer from misophonia often report that specific human sounds, including those made by breathing or whispering with any loudness can precipitate feelings of anger and disgust, in the absence of any previously learned associations that might otherwise explain those reactions.[84][85]

There are plentiful anecdotal reports by those who claim to have both misophonia and ASMR at multiple web-based user-interaction and discussion locations. Common to these reports is the experience of ASMR to some sounds, and misophonia in response to others.[86][87][88] In one case, a subject reports that the sound of someone whispering can precipitate ASMR or misophonia depending on who is producing it.[89]

Comparison with frisson

The tingling sensation that characterises ASMR has been compared and contrasted to 'frisson', which is a French word for 'shiver'.[90]

However, the English word 'shiver' signifies the rhythmic involuntary contraction of skeletal muscles which serves the function of generating heat in response to low temperatures, has variable duration, and is often reported subjectively as unpleasant. By distinction, the French word 'frisson', signifies a brief sensation usually reported as pleasurable and often expressed as an overwhelming emotional response to stimuli, such as a piece of music. Frisson often occurs simultaneously with piloerection, colloquially known as 'goosebumps', by which tiny muscles called arrector pili contract, causing body hair, particularly that on the limbs and back of the neck, to erect or 'stand on end'.[91][92][93][94]

Despite such comparisons, there is a majority consensus among those who form the 'ASMR community' that autonomous sensory meridian response is distinct from frisson; accordingly, moderators of the ASMR subreddit, which is the largest online focus of discussions on the subject with over 100,000 users, stipulate that topics related to frisson should be posted to the Frisson subreddit.[40][95]

Association with sexuality

There have been persistent efforts by many of those who form the 'ASMR community' to distinguish the euphoric sensation that characterizes ASMR from sexual arousal, and to differentiate video media created with intent to trigger it from pornography.[96][97]

Meanwhile, some journalists and commentators have drawn attention to the way in which many videos made as triggers are susceptible to being perceived as sexually provocative in a number of ways. Firstly, the use of objects as acoustic instruments and points of visual focus, accompanied by a softly spoken voice has been described as potentially fetishistic. Secondly, commentary and reporting on ASMR videos points out that the majority of 'ASMRtists' appearing in them are 'young attractive females', whose potential appeal is further allegedly sexualized by their use of a whispered vocal expression and gentleness of simulated touch purportedly associated exclusively with intimacy. The popularity of ASMR videos featuring women does substantially exceed those created by male performers. However, there are some popular male 'ASMRtists'.[22][36][97][98][99][100][101][102]

Representation in literature and the arts

Digital arts

The first digital arts installation specifically inspired by ASMR was by the American artist Julie Weitz and called Touch Museum, which opened at the Young Projects Gallery on 13 February 2015, and comprised video screenings distributed throughout seven rooms.[103][104][105][106]

Music

The music for Julie Weitz' Touch Museum digital arts installation was composed by Benjamin Wynn under his pseudonym 'Deru', and was the first musical composition specifically created for live ASMR arts event.[103]

Subsequently, artists Sophie Mallett and Marie Toseland created 'a live binaural sound work' composed of ASMR triggers, broadcast by Resonance FM, the listings for which advised the audience to 'listen with headphones for the full sensory effect'.[107][108]

On 18 May 2015, contemporary composer Holly Herndon released an album called Platform which included a collaboration with artist Claire Tolan named Lonely At The Top, intended to trigger ASMR.[109][110][111][112][113][114][115]

Film

There have been three successful crowd funded projects each based on proposals to make a film about ASMR, two documentaries and one fictional piece, none of which are currently completed.[116][117][118][119][120][121]

Fictional and creative literature

The American weekly hour-long radio program This American Life produced by WBEZ and hosted by Ira Glass[122] broadcast the first short story on the subject of ASMR, called A Tribe Called Rest, authored and read by American novelist and screenwriter Andrea Seigel[123]

Non-fiction

There is currently one non-fiction book on ASMR, part of the Idiot's Guide series.[50]

Statistics

In addition to the information collected from the 475 subjects who participated in the scientific investigation conducted by Nick Davies and Emma Barratt,[3] there have been two attempts to collate statistical data pertaining to the demographics, personal history, clinical conditions, and subjective experience of those who report susceptibility to ASMR.

Firstly, in December 2012, Craig Richard - a blogger on the subject of ASMR - published the first results of a poll comprising 12 questions that had received 161 respondents, followed by second results in August 2015 by which time there were 477 responses.[124][125]

Secondly, in August 2014, Craig Richard, Jennifer Allen, and Karissa Burnett published a survey at SurveyMonkey that was reviewed by Shenandoah University Institutional Review Board, and the Fuller Theological Seminary School of Psychology Human Studies Review Committee. In September 2015, when the survey had received 13000 responses, the publishers announced that they were analyzing the data with intent to publish the results. No such publication or report is yet available.[126][127]

See also

References

- ↑ Simner, Julia; Mulvenna, Catherine; Sagiv, Noam; Tsakanikos, Elias; Witherby, Sarah A.; Fraser, Christine; Scott, Kirsten; Ward, Jamie (2006). "Synaesthesia: the prevalence of atypical cross-modal experiences". Perception. 35 (8). doi:10.1068/p5469. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ↑ Banissy, Michael J.; Jonas, Clare; Cohen Kadosh, Roi (15 December 2014). "Synesthesia: an introduction". Frontiers in Psychology. 5 (1414). doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01414. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Barrat Emma, Davis Nick (2015). "Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR): a flow-like mental state". PeerJ. 3: e851. doi:10.7717/peerj.851. PMC 4380153

. PMID 25834771.

. PMID 25834771. - 1 2 3 Ahuja Nitin (2013). "It feels good to be measured: clinical role-play, Walker Percy, and the tingles". Perspectives in Biology and Medicine. 56 (3): 442–451. doi:10.1353/pbm.2013.0022. PMID 24375123.

- ↑ Allen, Jennifer (January 2015). Jennifer Allen Linked In Profile. LinkedIn. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- 1 2 Allen, Jennifer (25 February 2010). ASMR Facebook Group founded by Jennifer Allen. Facebook. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Simons, Hadlee (16 August 2012). 'An orgasm for your head?'. iAfrica. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Mitchell, Jennifer (2 September 2012). 'Latest social media craze: Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response'. The Maine Public Broadcasting Network. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Shropshall, Claire (6 September 2012). 'Braingasms and towel folding: the ASMR effect'. The Huffington Post. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Tufnell, Nicholas (27 February 2012). 'ASMR: orgasms for your brain'. The Huffington Post. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Lively, Daniel (19 April 2012). 'That tingling feeling: first international ASMR day'. The Corvallis Advocate. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- 1 2 'asmr0921' Podcast (21 September 2011). KCRadioGod.com. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Overton, Emma (22 October 2012). 'That funny feeling'. The McGill Daily. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Lindsay, Kathryn (15 August 2015). 'Inside the Sensual World of ASMRotica'. Broadly (Vice). Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Bronte, Georgia (17 December 2015). 'How ASMR purists got into a turf war over porn'. Vice. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ MacMuiris, Andrew (15 March 2010). 'Taking names: what do we call these tingles, then?' The Unnamed Feeling. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- 1 2 Ahuja, Nitin (2013). 'It Feels Good to Be Measured: clinical role-play, Walker Percy, and the tingles'. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine Vol. 56, No. 3. pp442-451. doi:10.1353/pbm.2013.0022 PMID 24375123

- ↑ Steady Health (19 October 2007). 'Weird Sensation Feels Good' Part 1. Forum Discussion at Steady Health. Steady Health. Retrieved 20 January 2016. The conversation entitled 'Weird Sensation Feels Good' began with its first post on 19 October 2007, which received 82 responses until the conversation moved to a fresh thread entitled 'Weird Sensation Feels Good Part 2'.

- ↑ Steady Health (20 December 2010). ''Weird Sensation Feels Good' Part 2. Forum Discussion at Steady Health' Forum Discussion at Steady Health. LifeForm Inc.. Retrieved 20 January 2016. The conversation entitled 'Weird Sensation Feels Good Part 2' began with its first post on 20 December 2010, which has 200 responses up to May 2015.

- ↑ Yahoo! Groups (12 December 2008). Society of Sensationalists Yahoo Group. Yahoo!. Retrieved 20 January 2016. The Society of Sensationalists Yahoo Group was active with its intended purpose from inception on 12 December 2008 until December 2014, accruing a total of 112 posts, after which it became inactive and a repository for spam posts.

- ↑ Reddit (28 February 2011). Subreddit ASMR Forum. Reddit. Retrieved 20 January 2016. The ASMR Subredit, which is a forum for user-generated content that includes sharing discovery of media related to ASMR, was formed on 28 February 2011, and by 31 December had over 100,000 registered users.

- 1 2 3 4 Manduley, Aida (February 2013). 'Intimate with strangers'. #24MAG, Issue 4, pp60–61. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- 1 2 The Young Turks (17 February 2013). 'ASMR videos - soothing or creepy?'. YouTube; retrieved 20 January 2016.

- 1 2 Green-Oliver, Heather (9 April 2013). 'I have ASMR, do you?', Northern Life; retrieved 20 January 2016.

- 1 2 Collins, Sean T. (10 September 2012). 'Why music gives you the chills'. BuzzFeed. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ ASMR Lab (April 2013). 'ASMR triggers - common asmr triggers that cause tingles'. The ASMR Lab Website. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Cox, Carolyn (2 September 2014). 'Brain Orgasms, Spidey Sense, and Bob Ross: A Look Inside The World Of ASMR'. The Mary Sue. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ ASMR Lab (2013). 'ASMR Triggers – Common ASMR triggers that cause tingles'.

- 1 2 Cheadle, Harry (31 July 2012). ASMR - the good feeling no one can explain. Vice. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 Fairyington, Stephanie (28 July 2014). Rustle, Tingle, Relax: The Compelling World of ASMR. New York Times Blog; retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Manduley, Aida (February 2013). 'Intimate with strangers'. #24MAG, Issue 4, pp60–61.Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Percy, Walker (2011). 'Love in the ruins: The adventures of a bad Catholic at a time near the end of the world'. Open Road Media; ISBN 9781453216200.

- 1 2 Ahuja, Nitin (2013). 'It feels good to be measured: clinical role-play, Walker Percy, and the tingles'. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine Vol. 56, No. 3. pp 442-51; doi:10.1353/pbm.2013.0022 PMID 24375123

- ↑ LifeForm Inc. (4 June 2015). 'About' the Steady Health Website. LifeForm Inc. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- 1 2 Steady Health (19 October 2007). 'Weird Sensation Feels Good' Part 1. Forum Discussion at Steady Health. LifeForm Inc.. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 Hudelson, Joshua (10 December 2012). 'Listening to whisperers: performance, ASMR community and fetish on YouTube'. Sound Studies Blog. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ O'Connell, Mark (12 February 2013). The Soft Bulletins. 'Could a one-hour video of someone whispering and brushing her hair change your life?'. Slate. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- 1 2 Yahoo! Groups (12 December 2008). Society of Sensationalists Yahoo Group. Yahoo!. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ MacMuiris, Andrew (February 2010). The Unnamed Feeling Blog. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Reddit (28 February 2011). Subreddit ASMR Forum. Reddit; retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Anonymous Poster to Is it Normal? (November 2009). 'Sensational feeling I get when talking to people'. Is it Normal?. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ pickledantique (7 October 2008). 'Tingly sensation on back of head when happy'. MedHelp Neurology Community; retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ odonate (23 June 2009).'Strange sensation in head'. eHealth Neurological Disorders Forum. eHealth Forum. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ avatarasong641 (2010). 'Sound from ear causes back tickle'. WebMD Ear, Nose and Throat Community. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Clemens, Setz (6 April 2015). 'High durch sich räuspernde Menschen'. Süddeutsche Zeitung. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Maslen, Hannah and Roache, Rebecca (30 July 2015). 'ASMR and absurdity'. Practical Ethics. Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Woolf, Virginia (2007) [1925]. "Mrs. Dalloway". The Selected Works; ISBN 978-1-84022-558-7.

- ↑ Bordonaro, Roberto (16 June 2013). 'ASMR and social grooming'. The ASMR Experiment. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Kuriki, Masahiko (2007). 'ASMR and social grooming'. Tokyo Maths. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- 1 2 Young, Julie, and Blansert, Ilse (2015). Idiot's Guides: ASMR. Idiot's Guides: ASMR. Penguin. ISBN 978-1615648184.

- ↑ Steady Health (20 December 2010). 'Weird Sensation Feels Good' Part 2. Forum Discussion at Steady Health Forum Discussion at Steady Health. LifeForm Inc.. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Westlund, Donna (5 May 2014). 'ASMR: the odd and pleasurable sensation felt only by some'. Liberty Voice; retrieved 20 January 2016.

- 1 2 Columbia University (2016). Professor Carl W. Bazil at Columbia University Medical Center. Columbia University Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Hockridge, Stephanie (16 May 2013). 'ASMR whisper therapy: does it work? relaxing, healing with sounds and a whisper'. ABC15.com. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Thinking Better (2008). Relaxation. Thinking Better; retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. (1990). Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. New York: Harper and Row. ISBN 0-06-092043-2

- ↑ 'Unintentional ASMR videos – random videos that give you the greatest tingles'.

- ↑ "The Soothing Sounds of Bob Ross". Newsweek.com. Retrieved 2016-04-21.

- ↑ "Is There Any Money To Be Made In ASMR?". Forbes.com. Retrieved 24 March 2016.

- 1 2 Lalwani, Mona (12 February 2015). ' Surrounded by sound: how 3D audio hacks your brain. A century-old audio technology is making a comeback thanks to VR', theverge.com, 12 February 2015.

- ↑ Hernandez, Patricia (28 November 2012).'This drug is legal. it's digital. and it's supposed to improve how you game. I put it to the test'. Kotaku Website; retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Binaural.com (April 1998) 'Binaural for beginners'. Binaural.com. Retrieved 20 January 2016. The Verge; retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ O'Connell, Mark (12 February 2013). The Soft Bulletins. 'Could a one-hour video of someone whispering and brushing her hair change your life?' Slate. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Manduley, Aida (February 2013). 'Intimate with strangers', #24MAG, Issue 4, pp 60–61; retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Mendonsa, Cristina (6 May 2013). 'ASMR: The sound that massages your brain', News10.Net; retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ↑ Andersen, Joceline (1 December 2015). Joceline Andersen's Profile at McGill University. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Andersen, Joceline (11 November 2014). ' Now you've got the shiveries: affect, intimacy, and the ASMR whisper community'. Television and New Media. Online version: doi:10.1177/1527476414556184. Subsequently published in print: Andersen, Joceline, 'Now you've got the shiveries: affect, intimacy, and the ASMR whisper community'. Television & New Media. Vol. 16, No. 8. pp683-700.

- ↑ Smith, Stephen; Fredborg, Beverley Katherine; Kornelsen, Jennifer (2015-08-14). "An examination of the default mode network in individuals with autonomous sensory meridian response (ASMR)". Social Neuroscience. Retrieved 2016-08-13.

In the current study, the default mode network (DMN) of 11 individuals with ASMR was contrasted to that of 11 matched controls.

- ↑ Lochte, Bryson (2013). Putative neural correlates of Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response. Undergraduate Thesis. Dartmouth College.

- ↑ Dartmouth College (2 October 2012). Dartmouth College Brain Imaging Laboratory Dartmouth College. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Kelly, William M. (19 January 2016). Professor William M. Kelly's Profile at Dartmouth College; retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Durkin, Kathryn (2014). 'Autonomous sensory meridian response:the role of ASMR as a therapeutic relaxation technique'. Trinity College Graduate Thesis.

- ↑ Lee, Randolph M. (1 January 2016). Randolph M. Lee Profile at Trinity College. Trinity College. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Huffenberger, Amy (2015). 'Empathy and euphoria: facial expression discrimination and Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response'. College of Wooster. Senior Independent Study Thesis. Paper 6677.

- ↑ Novella, Steven (12 March 2012). 'ASMR'. Neurologica Blog.New England Skeptical Society; retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Novella, Steven (12 March 2012). 'ASMR'. Skeptic Blog; retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Marsden, Rhodri (21 July 2012). 'Maria spends 20 minutes folding towels: why millions are mesmerised by ASMR videos'. The Independent. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Cytowic, Richard E. (2002). Synesthesia: a union of the senses (2nd edition). Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-03296-1. OCLC 49395033.

- ↑ Cytowic, Richard E. (2003). The man who tasted shapes. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-53255-7. OCLC 53186027.

- ↑ Cytowic, Richard E; Eagleman, David M (2009). Wednesday is indigo blue: discovering the brain of synesthesia. Cambridge: MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-01279-0.

- ↑ Harrison, John E.; Simon Baron-Cohen (1996). Synaesthesia: classic and contemporary readings. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-19764-8 OCLC 59664610.

- ↑ Naumer MJ, and van den Bosch, JJ (July 2009). Touching sounds: thalamocortical plasticity and the neural basis of multi-sensory integration. Journal of Neurophysiology. Vol. 102, No. 1. pp7-8. doi:10.1152%2Fjn.00209.2009 10.1152/jn.00209.2009. PubMed 19403745.

- ↑ Naumer MJ, van den Bosch JJ (July 2009). "Touching sounds: thalamocortical plasticity and the neural basis of multisensory integration". J. Neurophysiol. 102 (1): 7–8. doi:10.1152/jn.00209.2009. PMID 19403745.

- ↑ Schröder A, Vulink N, Denys D (2013). Fontenelle L, ed. "Misophonia: Diagnostic Criteria for a New Psychiatric Disorder". PLoS ONE. 8 (1): e54706. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0054706. ISSN 1932-6203.

- ↑ Life with Misophonia (9 June 2014). 'ASMR: the opposite of misophonia?' Life with Misophonia Blog. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ reddit_badger (2015). [TRIGGER WARNING] Misophonia and ASMR?. Reddit. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Pennsylvania State University (2015). 'ASMR and Misophonia: Sounds-Crazy! Science in our world: certainty and controversy'.

- ↑ Higa, Kerin (11 June 2015). 'Technicalities of the Tingles: The science of sounds that feel good. #ASMR'. Neuwrite. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ 4SSucks (2013). 'Misophonia and ASMR'. MD Junction. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Jones, Lucy (12 September 2012). 'Which moments in songs give you chills?' New Musical Express. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Define Frisson at Dictionary.com. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Huron, David Brian (2006). Sweet anticipation: music and the psychology of expectation. MIT Press. p.141. ISBN 978-0-262-08345-4.

- ↑ Huron, David Brian (1999). Music cognition handbook: a glossary of concepts. Ohio State University. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Salimpoor, V. N., Benovoy, M., Larcher, K., Dagher, A., and Zatorre, R. J. (2011). 'Anatomically distinct dopamine release during anticipation and experience of peak emotion to music'. Nature Neuroscience. Vol. 14, No. 2. pp257-262. doi:10.1038/nn.2726

- ↑ Lochte, Bryson (2013). Putative neural correlates of autonomous sensory meridian response. Undergraduate Thesis. Dartmouth College.

- ↑ Mashable (26 January 2015) 'All the feels. How a bunch of YouTubers discovered a tingling sensation nobody knew existed'. Mashable. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- 1 2 Etchells, Pete (8 January 2016). 'ASMR and 'head orgasms': what's the science behind it?' The Guardian. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Madrigal, Alexis C. (28 March 2015). 'Finally, psychologists publish a paper about ASMR, that tingly whispering YouTube thing'. Fusion. ABC Yahoo News Network. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Plante, Chris (9 September 2015). 'Is ASMR a "sex thing" and answers to questions you're afraid to ask about'. The Verge. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Waldron, Emma Leigh (14 December 2015). 'Mediated sexuality in ASMR videos'. Sound Studies Blog. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Reid-Smith, Tris (28 August 2013). 'How do you defeat anti gay trolls?' Gay Star News. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Hockridge, Stephanie (16 May 2013). 'ASMR whisper therapy: does it work? relaxing, healing with sounds and a whisper'. ABC15.com. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- 1 2 Picon, Jose (2015). 'Cutting the web: an art show for the digital age' 'Touch Museum' Reviewed in LA Canvas. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Vankin, Deborah (3 January 2016). Artist Julie Weitz breaks down "Touch Museum" videos'. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Webb, Nancy (January 2013) 'Sound into feeling, stone into flesh'. Julie Weitz. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Young Projects Gallery (November 2015). 'Touch Museum - Julie Weitz'. Young Projects Gallery. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Mallett, Sophie and Toseland, Marie (27 October 2015). Resonance FM Clear Spot Schedule. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Mallett, Sophie and Toseland, Marie (27 October 2015). Resonance FM Clear Spot Audio. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Beaumont-Thomas, Ben (26 April 2015). 'Holly Herndon: the queen of tech-topia'. The Guardian. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Zevolli, Giuseppe (2015). 'Holly Herndon (Past : Forward)'. Four by Three Magazine. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Sherburne, Philip (31 March 2015). 'Holly Herndon's collective vision'. Pitchfork. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Jacoby, Sarah (21 May 2015). 'Does this song trigger your ASMR?' Refinery29. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Corcoran, Nina (22 May 2015). 'Holly Herndon goes off the grid'. Consequence of Sound. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Kretowicz, Steph (13 May 2015). '10 people that inspired Holly Herndon's "Platform"'. Dummy. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Cliff, Aimee (13 May 2015). 'Holly Herndon’s new horizons'. Dazed. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Ragone, Lindsay (1 January 2013). 'Braingasm' film project on Kickstarter. Kickstarter. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Ragone, Lindsay, (January 2013). 'Braingasm' film website. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Mull, Kate (15 July 2013). 'Tingly Sensation' film project on Kickstarter. Kickstarter Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Mull, Kate (8 April 2013). 'Tingly Sensation' film Facebook page. Facebook. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Mull, Kate (15 July 2013). Kate Mull profile on Kickstarter. Kickstarter. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Cole, Graeme (July 2015). 'Murmurs' film project on Kickstarter. Kickstarter. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Abel, Jessica and Glass, Ira (1999). Radio: an illustrated guide. WBEZ Alliance Inc. ISBN 0-9679671-0-4.

- ↑ Seigel, Andrea (29 March 2013). 'A tribe called rest'. This American Life. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Richard, Craig (11 December 2014). 'ASMR data from website polls'. 'ASMR University' blog. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ 'ASMR data from website polls (August 2015 update)'. 'ASMR University' blog. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ "ASMR Surveys and Polls". ASMR Report. December 2015. Archived from the original on 2016-10-15. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

- ↑ Richard, Craig and Allen, Jennifer and Burnett, Karissa, (August 2014). ASMR Research Survey at SurveyMonkey. SurveyMonkey. Retrieved 20 January 2016.

External links

- "The ASMR Report". Archived from the original on 2016-03-24.

- What is ASMR?

- ASMRbar.com - Curated ASMR Videos and multimedia.