Maryland Army National Guard

| Maryland Army National Guard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Active | March 25, 1634–present |

| Country |

|

| Allegiance |

|

| Branch |

|

| Part of |

|

| Garrison/HQ | Baltimore, Maryland, United States |

| Nickname(s) | "The Maryland Line" (from the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War) |

| Motto(s) | "Fatti Maschii Parole Femine" ("Manly deeds, womanly words") |

| Commanders | |

| Commander, MD ARNG | Brig. Gen. Timothy E. Gowen, USA[1] |

| Insignia | |

| Crest |

|

| Distinctive unit insignia |

|

The Maryland Army National Guard (MD ARNG) is the United States Army component of the American state of Maryland. It is headquartered at the old Fifth Regiment Armory at the intersection of North Howard Street, 29th Division Street, near Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard in Baltimore and has additional units assigned and quartered at several regional armories, bases/camps and other facilities across the state.

Heraldic Items

Shoulder Sleeve Insignia

- Description: On a black disc 2 3⁄4 inches (6.99 cm) in diameter within a 1/8 inch (.32 cm) gold border, the shield of the Great Seal of Maryland Proper (1st and 4th quarters, yellow and black; 2nd and 3rd quarters, white and red).

- Background:

- The shoulder sleeve insignia was originally approved for Headquarters and Headquarters Detachment on 1949-03-08.

- It was redesignated with description amended for Headquarters, State Area Command, Maryland Army National Guard on 1983-12-30.

Distinctive Unit Insignia

- Description: A gold color metal and enamel device 7/8 inch (2.22 cm) high and 1 inch (2.54 cm) wide overall consisting of the shield, coronet, supporters and motto scroll and motto from the complete heraldic achievement of Lord Baltimore as delineated on the reverse side of the official seal of the State of Maryland and blazoned as follows:

- Shield (heraldic language description):

- Quarterly I and IV, paly of six pieces Or (gold) and Sable (black) a bend counterchanged; quarterly II and III, quarterly Argent (silver) and Gules (red) a cross bottony counterchanged.

- Above the shield an earl's coronet.

- Supporters: Dexter, a plowman Proper, holding a spade in dexter hand. Sinister, a fisherman Proper, holding a fish in sinister hand.

- Motto Scroll: A scroll folded in four undulating sections and inscribed "FATTI MASCHII PAROLE FEMINE" (Latin: "Deeds are Manly, Words are Womanly") all gold.

- Symbolism:

- The first and fourth (gold and black) quarters of the shield are the arms of the Calvert family and the second and third (silver (white) and red) quarters are those of the "Crossland family" which Cecilius Calvert, Second Lord Baltimore, (1605-1675), inherited from his maternal family side with grandmother, Alicia Crossland, wife of Leonard Calvert, the father of Sir George Calvert, (1579-1632), the first Lord Baltimore, and receiver of the first grant of land and charter for the newly established colonial Province of Maryland from King Charles I of the Kingdom of England in 1632, but died before the Colony was laid out and settled in 1634.

- The earl's coronet above the shield indicates that although Calvert was only a baron in England, he was considered of the higher noble rank of an earl or "count palatine" in Maryland.

- Background:

- The distinctive unit insignia was originally approved for Headquarters and Headquarters Detachment and non-color bearing units of the Maryland Army National Guard on 1971-04-09.

- It was amended to correct the spelling of the motto on 1971-06-08.

- The insignia was redesignated effective 1982-10-01 for Headquarters, State Area Command, Maryland Army National Guard.

- The distinctive unit insignia was amended to correct the spelling of the motto on 2001-12-07.

Crest

- Description: That for regiments and separate battalions of the Maryland Army National Guard: From a wreath of colors, a cross bottony per cross quarterly Gules and Argent.

- Symbolism: The crest and canton are from the arms of Lord Baltimore and appeared on the seal of the Province of Maryland probably as early as 1648.

- Background: The crest was approved for color bearing organizations of the State of Maryland on 1924-01-11.

- Note: This Crest is applied to the top of all Maryland National Guard Distinctive Unit Insignias to form the Unit Coat Of Arms.

Organization

The Maryland Army National Guard is organized into several major subordinate commands: the 58th Battlefield Surveillance Brigade (United States); the Combat Aviation Brigade, 29th Infantry Division; the 70th Regiment, a training unit; and the 58th Troop Command. The MSCs report to the Assistant Adjutant General for Army (TAAG-Army), who in turn reports to the Adjutant General (TAG). Both officers are appointed by the governor.

History

Colonial Militia

The Maryland National Guard traces its roots through the long-time previous colonial and state militia to March 1634, with the landing of two English militia captains from the two settlement expeditionary ships, the "Ark" and the "Dove" off the north shore of the Potomac River near the confluence with Chesapeake Bay at the first provincial capital, St. Mary's City in later St. Mary's County. It has a long and illustrious history.

American Revolutionary War

During the American Revolution, members of the "Maryland Line" repeatedly charged a vastly superior British force at the Battle of Long Island, buying time for the Continental Army to escape. It is from this incident that Maryland draws one of its official nicknames, "The Old Line State." This was the first time the American Army had used the bayonet in combat. Later in the war, the Maryland militia made a number of additional bayonet charges, including at Cowpens, where their charge turned impending defeat into victory, and at Guilford Courthouse, where they forced the elite British Foot Guards to retreat.

War of 1812

During the War of 1812, the Maryland militia held the line at the Battle of North Point in 1814, commanded by Brigadier General John Stricker. There, they held up the British attack for two hours, long enough for the defense of Baltimore to be shored up. The British forces, many of whom were veterans of the Napoleonic Wars took around 300 casualties and, though the Americans retreated from the field at North Point, the British would eventually turn back rather than attempt an assault on the American defenses at Baltimore.[2] Not all the militia regiments performed with equal distinction. The 51st, and some members of 39th, broke and ran under fire. However, the 5th and 27th held their ground and were able to retreat in good order having inflicted significant casualties on the advancing enemy.[3] The 175th Infantry (ARNG MD), derived from the 5th Regiment, is one of only nineteen Army National Guard units with campaign credit for the War of 1812.

American Civil War

From 1841 to 1861 the senior militia general was Major General George H. Steuart, commander of the First Light Division.[4] Until the Civil War he would be the senior commander of the Maryland Volunteers.

In 1833 a number of Baltimore regiments were formed into a brigade, and Steuart was promoted from colonel to brigadier general.[5] From 1841 to 1861 he was Commander of the First Light Division, Maryland Volunteer Militia.[4] Until the Civil War he would be the Commander-in-Chief of the Maryland Volunteers.[6][7] The First Light Division comprised two brigades: the 1st Light Brigade and the 2nd Brigade. The First Brigade consisted of the 1st Cavalry, 1st Artillery, and 5th Infantry regiments. The 2nd Brigade was composed of the 1st Rifle Regiment and the 53rd Infantry Regiment, and the Battalion of Baltimore City Guards.[8]

By April 1861 it had become clear that war was inevitable. On April 16 Steuart's son, George H. Steuart, then an officer in the United States Army, resigned his captain's commission to join the Confederacy.[9] On April 19 Baltimore was disrupted by riots, during which Southern sympathizers attacked Union troops passing through the city by rail. Steuart's son commanded one of the Baltimore city militias during the disturbances of April 1861, following which Federal troops occupied the city. In a letter to his father, the younger Steuart wrote:

- "I found nothing but disgust in my observations along the route and in the place I came to - a large majority of the population are insane on the one idea of loyalty to the Union and the legislature is so diminished and unreliable that I rejoiced to hear that they intended to adjourn...it seems that we are doomed to be trodden on by these troops who have taken military possession of our State, and seem determined to commit all the outrages of an invading army."[10]

Steuart himself was strongly sympathetic to the Confederacy and, perhaps knowing this, Governor Hicks did not call out the militia to suppress the riots.[11] On May 13, 1861 Union troops occupied the state, restoring order and preventing a vote in favour of Southern secession. Steuart moved south for the duration of the American Civil War, and much of the general's property was confiscated by the Federal Government as a consequence. Old Steuart Hall was confiscated by the Union Army and Jarvis Hospital was erected on the estate, to care for Federal wounded.[12] However, many members of the newly formed Maryland Line in the Confederate army would be drawn from the state militia.[13]

Maryland militia units fought on both sides of the Civil War. At the Battle of Front Royal, the Union 1st Maryland was engaged and defeated by the Confederate 1st Maryland. The lineage of the Confederate 1st Maryland is perpetuated by the 175th Infantry Regiment, whose lineage dates back to 1774.

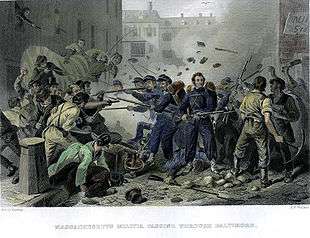

Great Railroad Strike of 1877

During the Great Railroad Strike of 1877, on July 20 Governor Carroll called up the 5th and 6th Regiments from Baltimore to stop strikers in Cumberland from disrupting rail service. While marching from their armories to a Baltimore and Ohio Railroad train at Camden Station, an armed mob attacked the troops. The 6th Regiment fired on the mob, killing 10 and wounding 25, and several members of both regiments were injured by stones and bricks.[14] The troops were then besieged by 15,000 rioters inside Camden Yards until the arrival of federal troops in Baltimore. The building, now part of Camden Yards baseball stadium, still bears bullet holes from rioters firing at troops inside.

Mexican Border raids of 1916

In response to Pancho Villa’s cross-border raids, the Maryland National Guard was called up in 1916 and deployed for seven months to the town of Eagle Pass, Texas, on the Mexican border.[15]

World War I

During the First World War, most Maryland National Guard troops served as part of the 29th Division, and their campaign credits include Meuse-Argonne. In addition, the 1st Separate Company, an all-black unit, served as part of the 372nd Infantry Regiment, although ostensibly assigned to the 93rd Division, actually fought under French control. One of the Maryland National Guard's longest-mobilized units during the war was the 117th Trench Mortar Battery, which served under the 42nd Division from October 1917 until the end of the war. It was the first Maryland unit to see combat, and participated in all of the AEF's major battles during that period.

World War II

World War II also saw the mobilization of the Maryland National Guard. Again, most were assigned to the 29th Infantry Division, where they took part in the D-Day landings and fought their way across France and Germany. In 1945, they missed being the first unit to link up with the Soviet Red Army on the Elbe River by a matter of hours.

Korean War

The Maryland National Guard had very few troops mobilized for the Korean War, but those that were played an important role. The 231st Transportation Truck Battalion was the first National Guard unit to land in Korea, and were immediately put to use keeping supplies flowing within the Pusan Perimeter. Originally a segregated, all-black unit, the 231st was integrated during this service in Korea, only to be again segregated when it returned to state status.

Cold War

Although no Maryland Army National Guard units served in Vietnam, the Maryland Army Guard played a significant role during the Cold War. Across the state, Nike missile batteries, armed with nuclear warheads, were manned by Maryland National Guardsmen to defend the National Capital area from Soviet bombers from the mid-1950s until the early 1970s. Maryland National Guard troops were also kept busy with riot-control duty in the 1960s and early 1970s, most notably during the Baltimore Riots of 1968, the Salisbury riots of May, 1968, the University of Maryland student riots of 1970-72, and the Cambridge Riots of 1963 and 1967.[16]

Gulf War

200th and 290th Military Police Companies November 1990 - April 1991 - deployed to Saudi Arabi near the Iraq border in support of Operations Desert Shield/Storm.

Global War on Terrorism

Since the September 11 attacks, the Maryland Army National Guard has mobilized a number of units, including the 58th Infantry Brigade Combat Team, for service in Iraq; Afghanistan; Guantanamo Bay, Cuba; and Kosovo. Guardsmen from the 115th Military Police Battalion were among the first and most heavily called upon, having arrived at the Pentagon on September 12 and subsequently served in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Guantanamo Bay. Maryland elements of the Combat Aviation Brigade, 29th Infantry Division served in Iraq, Maryland elements of the Combat Aviation Brigade, 42nd Infantry Division served in Afghanistan, and Maryland National Guard elements were attached to 44th Medical Brigade/XVIII Airborne Corps for service in Iraq. Maryland is also home to several Special Operations units, most notably Company B, 2nd Battalion, 20th Special Forces Group (Airborne) and Special Operations Detachment, Joint Forces. Members of these units have both been mobilized to serve in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Currently, the Special Operations Detachment, Joint Forces was selected and mobilized to create the Special Operations Command for the newly created United States Africa Command.

Despite the GWOT's call and response for MDARNG units to enlist or volunteer for a Post September 11, 2001, theater of new deployments , MDARNG left many wounded soldiers who served in OEF and OIF with no benefits for periods of up and over a decade after soldiers injuries occurred; injuries such as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder [PTSD], Traumatic Brain Injury [TBI], anatomical losses were not covered under statue or army regulation/national guard regulation. This epic cycle of information for Post 911 Security Studies does suggest the neglect of the MDARNG against her soldiers was unfortunately the most humiliating de facto loss of the MDARNG's military history and MDARNG's ability to even suggest they are a state organization which can assimilate under both the ideas of a military philosophy and military medical sciences for the war wounded of Post 911 military operations. Under MDARNG's current organizational and command status, MDARNG cannot assimilate these ethical tasks which are required of them in repetitive tedium of being associated with the United States Army in complete fashion that an alethic army of the United States is something which MDARNG can't commit to actively being part of. [17]

Historic units

-

115th Armor Regiment (United States)

115th Armor Regiment (United States) -

158th Cavalry Regiment (United States)

158th Cavalry Regiment (United States) -

110th Field Artillery Regiment (United States)

110th Field Artillery Regiment (United States) -

224th Field Artillery Regiment (United States)

224th Field Artillery Regiment (United States) -

115th Infantry Regiment (United States)

115th Infantry Regiment (United States) -

175th Infantry Regiment (United States)

175th Infantry Regiment (United States) -

224th Aviation Regiment (United States)

224th Aviation Regiment (United States) -

121st Engineer Battalion (United States)

121st Engineer Battalion (United States)

Current Units

- Joint Forces Headquarters

- Medical Detachment

- Training Support Detachment

- 32nd Civil Support Team (WMD)

- Recruiting & Retention Battalion

.jpg) Maryland National Guard soldiers watch protesters gathered in front of Baltimore City Hall, 30 April 2015

Maryland National Guard soldiers watch protesters gathered in front of Baltimore City Hall, 30 April 2015 - Recruit Sustainment Program

- 58th Troop Command

- HHD 115th Military Police Battalion

- 200th Military Police Company

- 290th Military Police Company

- 29th Military Police Company

- HHC 1297th Support Battalion

- 29th Mobile Public Affairs Detachment

- 1729th Maintenance Company

- 1229th Transportation Company

- 224th Medical Company

- 104th Medical Company

- 581st Troop Command

- 231st Chemical Company

- 243rd Engineer Haul Team

- 244th Engineer Company (Vertical)

- 253d Engineer Company (Sapper)

- 229th Army Band

- 291st Digital Liaison Detachment

- Det 2, HHD, 2 Battalion, 20th Special Forces Group

- 70th Regiment

- 58th Battlefield Surveillance Brigade

- Headquarters - Headquarters Company

- 1st Battalion, 175th Infantry Regiment, assigned to the 28th Infantry Division, Pennsylvania Army National Guard when in federal use

- 325th Military Intelligence Battalion (USAR), Hartford, CT

- 110th Information Operations Battalion

- 729th Support Company

- 629th Signal Company (Network Support)

- 29th Infantry Division Combat Aviation Brigade

- Det 1, HSC, 29th ID

- Company C, Signal 29th ID

- Company B I&S 29th ID

Notable members

- Raymond Berry, professional football Hall of Fame inductee

- John R. Bolton, United States Representative to the United Nations

- D. John Markey, 1946 senatorial candidate

- James Morris, Grammy Award-winning opera baritone

- Clinton L. Riggs, Secretary of Commerce and Police of the Philippine Commission

See also

References

- ↑ http://www.md.ngb.army.mil/absolutenm/templates/?a=725&z=39

- ↑

- ↑ George, Christopher. Terror on the Chesapeake - The War of 1812 on the Bay. White Mane Books, Shippensberg, Pennsylvania (2000).

- 1 2 Sullivan David M., The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War: The First Year, p.286, White Mane Publishing (1997). Retrieved Jan 13 2010

- ↑ Griffith, Thomas W., p.257, Annals of Baltimore, 1833 Retrieved February 28, 2010

- ↑ Hartzler, Daniel D., p.13, A Band of Brothers: Photographic Epilogue to Marylanders in the Confederacy Retrieved March 1, 2010

- ↑ Niles Weekly register, Volume 62, p.177 Retrieved March 2, 2010

- ↑ Field, Ron, et al., p.33, The Confederate Army 1861-65: Missouri, Kentucky & Maryland Osprey Publishing (2008), Retrieved May 10, 2010

- ↑ Cullum, George Washington, p.226, Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the U.S. Military Retrieved Jan 16 2010

- ↑ Mitchell, Charles W., p.102, Maryland Voices of the Civil War. Retrieved February 26, 2010

- ↑ Maryland, A Middle Temperament: 1634–1980 by Robert J. Brugger, Johns Hopkins University Press (1996) Retrieved Jan 15 2010

- ↑ Nelker, p.120

- ↑ Goldsborough, p.9

- ↑ Scharf, J. Thomas (1967 (reissue of 1879 ed.)), History of Maryland From the Earliest Period to the Present Day, 3, Hatboro, PA: Tradition Press, pp. 733–42 Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "History of Maryland National Guard". Maryland National Guard. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- ↑ Balkoski, Joseph. The Maryland National Guard: A History of Maryland's Military Forces. Baltimore: Maryland Military Department. 1991.

- ↑ [Stephen Verges - Georgetown University - September 11, 2001 First Responder and blinded veteran from MDARNG - srv8*georgetown*edu

- ↑ http://www.md.ngb.army.mil/XHTML/Organization/UnitLocator.html

- Goldsborough, W. W., The Maryland Line in the Confederate Army, Guggenheimer Weil & Co (1900), ISBN 0-913419-00-1.

External links

- Maryland Military Historical Society

- Bibliography of Maryland Army National Guard History compiled by the United States Army Center of Military History