Battle of the Lippe

| Battle of the Lippe | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eighty Years' War | |||||||

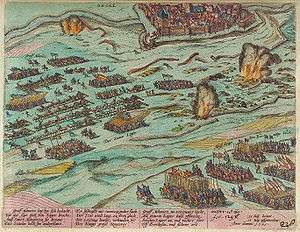

'Defeat of the Dutch States Army near Wesel, 1595'. By Simon Frisius and Frans Hogenberg. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Cristóbal de Mondragón Juan de Córdoba |

Maurice of Nassau Philip of Nassau (DOW) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 500 cavalry | 500–700 cavalry | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 60 | 100–300 | ||||||

The Battle of the Lippe was a cavalry action fought on 2 September 1595 on the banks of the Lippe river, in Germany, between a corps of Spanish cavalry led by Juan de Córdoba and a corps of Dutch cavalry, supported by English troops, led by Philip of Nassau. The Dutch statholder Maurice of Nassau, taking advantage of the fact that the bulk of the Spanish army was busied in operations in France, besieged the town of Groenlo in Gelderland, but the elderly governor of the citadel of Antwerp, Cristóbal de Mondragón, organized a relief army and forced Maurice to lift the siege. Mondragón next moved to Wesel, positioning his troops on the southern bank of the Lippe river to cover Rheinberg from a Dutch attack. Maurice aimed then, relying on his superior army, to entice Mondragón into a pitched battle, planning to use an ambush to draw the Spanish army into a trap. However, the plan was discovered by the Spanish commander, who organized a counter-ambush.

The Dutch intended to overtake a Spanish foraging convoy and deliver it into their camp in order to draw the Spanish army in pursuit to the banks of the Lippe, where Maurice was awaiting with the Dutch States Army in order of battle. However, Mondragón reinforced the escort of the convoy and hid a large force of cavalry in a wood nearby under his lieutenant Juan de Córdoba. Thanks to Mondragón's long experience, the Spanish routed the Dutch force and inflicted a number of casualties upon Philip of Nassau's men, including himself and several other high-ranking Dutch and English officers in the Dutch army.

Background

In 1595, Henry IV of France declared war on Spain in response to Philip II's continued support of the Catholic League of France, and formed an alliance with Elizabeth I of England and the Dutch Republic, who were engaged in their own wars against the Spanish Crown.[1] The Catholic Netherlands were, consequently, caught between two fronts, and French and Dutch forces even tried to create a corridor linking their respective states through the Prince-Bishopric of Liège.[2] The new Governor-General of the Spanish Netherlands, the Count of Fuentes, directed his efforts against Picardy and Cambrésis, leaving a few troops to defend the loyal provinces from a Dutch attack.[3]

In July, while Fuentes was busied in the siege of Doullens, Maurice of Nassau, statholder of the Dutch Republic, assembled a force of 6,000 infantry, some cavalry companies and 16 artillery pieces of the Dutch States Army,[lower-alpha 1] and led them under the walls of Groenlo, a medium-sized town in the County of Zutphen. Its northern flank defended by the Slinge, a stream of the Berkel river, Groenlo was fortified with five bulwarks and garrisoned by 11 infantry companies from Count Herman van den Bergh's regiment numbering 600 troops under Jan van Stirum, a German officer, and four small artillery pieces.[4][5][6]

On receiving news of the siege, Cristóbal de Mondragón, the elderly Spanish governor of Antwerp, whom Fuentes had left in command of the Spanish forces opposite to the Dutch, collected a little army gathering forces of several garrisons and marched to Groenlo through Brabant and Gelderland.[7] Mondragón's force comprised two Spanish tercios (under Luis de Velasco and Antonio de Zúñiga),[8] an Irish regiment under William Stanley, a Swiss regiment and 1,300 cavalry under Juan de Córdoba, which, having crossed the Meuse at Venlo, were joined by Frederick van den Bergh's German regiment.[4]

At over 80,[9][lower-alpha 2] Mondragón was still able to mount on horseback, though he had to be helped by two men and could only wear light armour.[10] He first came to prominence at the Battle of Mühlberg, in 1547, and was one of the few Spanish officers of good fame in the rebel provinces, being portrayed in a positive light by contemporaneous Dutch authors such as Hugo Grotius and Pieter Corneliszoon Hooft.[11] Mondragón planned not only to relieve Groenlo, but also to lure Maurice into a pitched battle.[7] The Dutch general, however, on receiving news of his enemy's march, set fire to supplies, tools and ammunitions gathered for the siege and retreated two miles out of Groenlo.[6] Mondragón could therefore ressuply the town unmolested.[7]

Prelude

After Groenlo was secured, Mondragón marched south to Rheinberg to cover the town from a Dutch attack. He encamped his army near Wesel, at Dinslaken, while Maurice followed him and took up positions at Bislich, both armies being separated by the Lippe river.[7] The Spanish position was strong; the rearguard and the left flank covered by the Rhine and the right flank by the Lippe and a range of moorland hills called Testerburg.[12] For several weeks both armies looked at each other, often skirmishing when both cavalries sallied to forage.[7] As time passed, the Spanish foragers were forced to look for victuals two or three leagues far away from their camp.[13] Maurice took the opportunity to plan a mock ambush on Mondragón's foraging convoy aiming to lure him into a general action in which he could destroy the Spanish army. Mondragón also hoped to lure his enemy into a trap.[6]

On 1 September, Maurice gave the command of the ambush to his favourite commander, his cousin Philip of Nassau.[14] Maurice instructed him to cross the Lippe river the following day at dawn, hide in a wood next to which the Spanish convoy was expected to pass, and fall on its guard.[15] Maurice's goal was to seize the foraging convoy, separate it from the escort and lead it to the Dutch camp, thus forcing Mondragón to intervene with a larger force.[6] Then, after the appearance of Mondragón with the main army, Nassau was to retreat to the Dutch camp, thus luring the Spanish army into an ambush.[14] For his task, Nassau received the command of some 500 or 700 Dutch and English horsemen and was accompanied by his two brothers, Ernst Casimir and Ludwig Gunther, as well as several other Dutch officers, Count Ernst of Solms, Paul and Marcellus Bacx, and the English captains Nicholas Parker, Cutler and Robert Vere.[14]

The Dutch intentions were anticipated by the Spanish. According to Joseph de La Pise, a French jurist hired by Maurice's half brother and successor Frederick Henry to write a history of the Princes of Orange,[16] Mondragón had learned of the ambush from English soldiers who had deserted from the Dutch colours,[17] but the Italian Jesuit Angello Gallucci claims that it was Spanish spies who informed Mondragón,[18] who had used spies to gather information on the enemy since the siege of Zierikzee, in 1576.[19] In any case, the Spanish general took measures to turn Nassau's surprise into a trap. The convoy, normally guarded by 300 infantry and 150 cavalry, was reinforced by 300 musketeers and a large force of cavalry under Mondragón's lieutenant, Juan de Córdoba.[19]

Action

On 2 September, at dawn, the Dutch force crossed the Lippe across a pontoon bridge. Maurice awaited them with 5,000 infantry and the rest of his cavalry arranged for the battle in the hills near Wesel, along the opposite riverbank.[14] Philip of Nassau divided his troops into four squadrons: the first one of 125 men under the drossaard of Sallandt, the second one of 125 men under the Count of Kinsky, the third one, those in which Nassau and his brothers marched, of 150 soldiers under Lieutenant Balen, and the last, closing the way, of 120 men under the English captain Nicholas Parker.[6] Having arrived at Krudenburg, Nassau sent 40 chosen men from the companies led by Balen to surprise the foraging horses. On finding a force much larger than they expected, the Dutch officers thought that something was wrong and sent a report back to Philip of Nassau.[20] The Dutch commander, nevertheless, believed that it was only the convoy's escort and moved on with his troops and his entourage to attack the Spanish cavalry, aiming to prevent its escape.[20]

The Dutch officers' report was not mistaken: early in the morning, two Spanish scouts had found the track of the Dutch force crossing the river, and Mondragón, anticipating them, had deployed his cavalry beyond a beechwood,[6] the countryside southwards the Lippe being covered by small woods alternating with moorlands.[19] Besides the troops guarding the convoy, Juan de Córdoba had the command of at least seven cavalry companies: those of Hendrik van den Bergh, Girolamo Caraffa, Carlo Maria Caracciolo, Paulo Emilio Martinengo, his own company,[21] 's-Hertogenbosch lances under Adolf van den Bergh and Sancho de Leyva's company.[22] Other authors also list Alonso Mendo's company. Mondragón had informed the guard of the convoy of the Dutch intentions and encouraged the soldiers to hold their ground, promising them that he was behind them with the whole Spanish army to come in relief.[23]

Commanding 75 lances from Kinsky's company, and followed by the bulk of his force, Nassau passed through a narrow path in a small forest, and, coming out to open field, was surprised by the Spanish troops,[20] namely by those under Hendrik van den Bergh, followed by Carlo Maria Caracciolo and the 's-Hertogenbosch lances.[21] Van den Bergh's harquebusiers, discovering the Dutch column emerging from the forest, fired a volley and, turning right, clashed with the Dutch scouts, starting the action.[13] There was then a firece fight. The Dutch troops were formed into eight squadrons, but caught by surprise in a narrow passage, the Dutch soldiers were unable to use their lances, so they were forced to defend themselves with swords and pistols.[20] Philip of Nassau, his brothers and their cousin Ernst von Solms were seriously wounded and dismounted at the beginning the fight. Kinsky's and Balen's troops, coming in relief, were unable to rescue the wounded commanders, and some Dutch soldiers started to flee from the battlefield.[17] Nicholas Parker, however, managed to collect the fugitives and, renewing the action, he put disorder into the Spanish cavalry. The encounter turned then a general action out the wood, in open ground.[18]

At first the Dutch were winning the action, but after they put in disorder two or three Spanish squadrons, Paulo Emilio Martinengo charged ahead his company on their flank and in turn routed a Dutch squadron, which allowed Córdoba to regroup his troops and renew the attack, this time with success.[21] Despite the stubborn resistance offered by the Dutch troops, they were finally broken and fled in a disorderly fashion, attempting to save themselves before the Lippe river. Córdoba sent his cavalry to follow them up, and they found that some of the Dutch soldiers, having been unable to find a good place to ford the river, had drowned.[21] The Spanish captives were freed, and the spoils taken by the Dutch recovered.[18]

Aftermath

.jpg)

The battle is noted for the heavy death toll among the Dutch commanders. Philip of Nassau was mortally wounded at the beginning of the action, shot at point blank range through the body with an harquebus, his robes being set on fire.[24] Robert Vere, brother of the English colonel Horace Vere, was slain by a lance thrust in the face.[25] The drossaard of Zallandt and Count Ferdinand Kinsky were also killed. Count Ernst of Solms was seriously wounded and captured. Together with Philip, he was carried to Rheinberg, where both soldiers were visited by Mondragón and their Catholic cousins, the Van den Bergh brothers, and treated by the Spanish surgeons.[26] Despite all the attentions, both Dutch commanders died of the wounds they had sustained; Nassau the night after the battle, and Solms three days later.[26] Count Ernst Casimir was captured and ransomed for 10,000 florins.[24] Mondragón dispatched him to Maurice of Nassau with the bodies of the dead counts, which were buried with honours at Arnhem.[26]

As for the battle losses, sources vary. The Flemish Protestant Guillaume Baudart set Dutch losses at 88 horses, 83 prisoners and 24 killed.[27] The Italian Cardinal Guido Bentivoglio claimed that more than 300 Dutch soldiers were slain as opposed to about 60 Spanish casualties.[28] The Roman Jesuit Angelo Gallucci also wrote of 300 Dutch casualties.[29] The Spanish soldier and writer Carlos Coloma set the Spanish loss as 19 men killed and claimed that the Dutch force lost three flags and about 400 serviceable horses.[22] On the Spanish side the only soldiers of note among the casualties were Caraffa, Martinengo and Caracciolo, all of whom were wounded, but not mortally.[29] Joseph de La Pise stated that the Dutch took seven Spanish prisoners and 15 horses.[26] According to Antonio Carnero, accountant in the Spanish army, an envoy of the King of France to the Dutch camp was present at the battle and found later among the fatalities.[21]

The English author Edward Grimeston wrote, in his book A General History of the Netherlands, that the battle of the Lippe "was a pettie battaile of young and hot blouds, who prooved but bad Marchants that got nothing".[30] Even though it was only a small battle, it was celebrated joyfully at the Spanish camp before Cambrai. Three salvos were fired upon the city by 87 artillery pieces and 6,000 muskets and arquebuses.[31] The North-American historian John Lothrop Motley highlighted the key role played by the 91-year-old Mondragón in the Spanish victory:

This skirmish on the Lippe has no special significance in a military point of view, but it derives more than a passing interest, not only from the death of many a brave and distinguished soldier, but for the illustration of human vigour triumphing, both physically and mentally, over the infirmities of old age, given by the achievement of Christopher Mondragon. Alone he had planned his expedition across the country from Antwerp, alone he had insisted on crossing the Rhine, while younger soldiers hesitated; alone, with his own active brain and busy hands, he had outwitted the famous young chieftain of the Netherlands, counteracted his subtle policy, and set the counter-ambush by which his choicest cavalry were cut to pieces, and one of his bravest generals slain. So far could the icy blood of ninety-two prevail against the vigour of twenty-eight.— John Lothrop Motley History of the United Netherlands: from the death of William the Silent to the twelve years' truce. Vol. 2, p. 341

The Spanish and Dutch armies spent 16 more days observing each other from their encampments, but no action of importance ensued. Maurice of Nassau laid a bridge over the Rhine and tried to take Meurs by surprise, but the enterprise was discovered.[32] He also committed Count William Louis of Nassau-Dillenburg to intercept five Spanish companies sent by Mondragón to lodge in Twente, but the Spaniards managed to reach Enschede, leaving only a few chariots with supplies in Dutch hands.[32] On 11 October, lacking of forage, Mondragón retired back to Brabant. Maurice aimed to cut off his retreat, but the Spaniard succeeded in bringing his troops to a secure position.[33] Mondragón re-crossed the Meuse in November and distributed his troops in different towns. Before crossing the river the Swiss mercenaries were paid and liscended.[34] On 4 January 1596, the elderly general died in the citadel of Antwerp.[33] On his deathbed he wrote a letter to Philip II asking for the castellany of Antwerp for his son Alonso and a company of lances for his grandson Cristóbal, but both requests were denied.[35]

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ Angello Gallucci accounts 8,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry, while Carlos Coloma numbers 10,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry. The number of cannons is given also as 17 or 18 by different sources.

- ↑ Early sources put Mondragón's birth year as 1504, but later sources give it as 1514.

Citations

- ↑ Nexon, p. 230

- ↑ Morris, p. 276

- ↑ Wernham, p. 29

- 1 2 Coloma, p. 380.

- ↑ Gallucci, p. 288

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 De la Pise, p. 640

- 1 2 3 4 5 Motley, p. 337

- ↑ Villalobos y Benavides, p. 110.

- ↑ de Atienza, p. 288

- ↑ Villalobos y Benavides, p. 116.

- ↑ Fagel, p. 77

- ↑ Henty, p. 331

- 1 2 Coloma, p. 381

- 1 2 3 4 Motley, p. 338

- ↑ Gallucci, p. 290

- ↑ Frijhoff, p. 95

- 1 2 De La Pise, p. 641

- 1 2 3 Gallucci, p. 291

- 1 2 3 Salcedo y Ruiz, p. 183.

- 1 2 3 4 Motley, p. 339

- 1 2 3 4 5 Carnero, p. 375

- 1 2 Coloma, p. 382

- ↑ Villalobos y Benavides, p. 113.

- 1 2 Motley, p. 340

- ↑ Henty, p. 332

- 1 2 3 4 De la Pise, p. 642

- ↑ Baudart, p. 226

- ↑ Bentivoglio, p. 388

- 1 2 Gallucci, p. 292

- ↑ Grimeston, p. 1104

- ↑ Coloma, p. 379.

- 1 2 De la Pise, p. 643.

- 1 2 Motley, p. 342

- ↑ Coloma, p. 399

- ↑ Salcedo y Ruiz, p. 186.

Bibliography

- de Atienza y Navajas (barón de Cobos de Belchite), Julio (1993). La obra de Julio de Atienza y Navajas, barón de Cobos de Belchite y marqués del Vado Glorioso, en "Hidalguía". Ediciones Hidalguia. ISBN 978-84-87204-55-5.

- Baudart, Guilleaume (1616). Les guerres de Nassau (in French). Amsterdam: M. Colin. OCLC 63273522.

- Villalobos y Benavides, Diego (1876). Comentarios de las cosas sucedidas en los Paises Baxos de Flandes desde el año de 1594 hasta el de 1598 (in Spanish). Madrid: Alfonso Durán. OCLC 1878524.

- Bentivoglio, Guido (1687). Las guerras de Flandes (in Spanish). Antwerp: Geronymo Verdussen. OCLC 57625539.

- Carnero, Antonio (1625). Historia de las guerras civiles que ha avido en los estados de Flandes des del año 1559 hasta el de 1609 y las causas de la rebelion de dichos estados (in Spanish). Brussels: en casa de Juan de Meerbeque. OCLC 433106763.

- Coloma, Carlos (1635). Las guerras de los Estados Baxos desde el año de M.D.LXXX.VIII. hasta el de M.D.XCIX. (in Spanish). Antwerp: Juan Bellero. OCLC 433106484.

- De La Pise, Joseph (1639). Tableau de l'histoire des princes & principauté d'Orange, divisé en quatre parties, selon les quatre races qui y ont regné souverainement depuis l'an 793 (in French). The Hague: Theodore Maire. OCLC 781611994.

- Fagel, Raymond (2009). "La imagen de dos militares españoles decentes en el ejército del Duque de Alba en Flandes: Cristóbal de Mondragón y Gaspar de Robles". In Collard, Patrick. Encuentros de ayer y reencuentros de hoy. Flandes, Países Bajos y el Mundo Hispánico en los siglos XVI-XVII (in Spanish). Ghent: Academia Press. ISBN 9789038215273.

- Frijhoff, Willem; Spies, Marijke (2004). Dutch Culture in a European Perspective: 1650, Hard-won Unity. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1403932271.

- Gallucci, Angelo (1673). Historia della guerra di Fiandra dall'anno 1593. sin alla tregua d'anni 12. conchiusa l'anno 1609. (in Italian). Rome: Ignatio de Lazari. OCLC 433391837.

- Grimeston, Edward (1609). A Generall Historie of the Netherlands. London: A. Islip, and G. Eld. OCLC 265495924.

- Henty, George Alfred (1891). By England's Aid, Or The Freeing of the Netherlands (1585–1604). London: Blackie & Son. OCLC 26944050.

- Morris, Terence Alan (2002). Europe and England in the Sixteenth Century. London: Routledge. ISBN 9780415150415.

- Motley, John Lothrop (1888). History of the United Netherlands: From the Death of William the Silent to the Twelve Years' Truce. New York: Harper & Brothers. OCLC 8903843.

- Nexon, Daniel H. (2009). The Struggle for Power in Early Modern Europe: Religious Conflict, Dynastic Empires, and International Change. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400830800.

- Salcedo y Ruiz, Ángel (1905). El coronel Cristóbal de Mondragón: apuntes para su biografía (in Spanish). Madrid: Marceliano Tabarés. OCLC 796334345.

- Wernham, R. B. (1994). The Return of the Armadas: The Last Years of the Elizabethan War against Spain 1595–1603. New York: Oxford University Press. OCLC 28292868.