Siege of Venlo (1637)

| Siege of Venlo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Eighty Years' War | |||||||

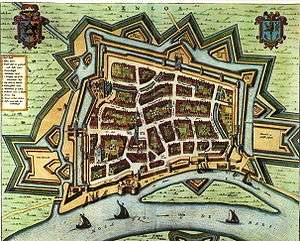

Map of Venlo in 1652, by Joan Blaeu. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand | Nicolaas van Brederode | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 17,000 soldiers[1][2][3] |

1,200 soldiers[1][2][3] Unknown number of burghers | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Minor | 1,200 (mostly prisoners) | ||||||

The Siege of Venlo was an important siege in the Eighty Years' War that lasted from 20 to 25 August, 1637. The Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand of Austria, Governor of the Spanish Netherlands, retook the city of Venlo from the United Provinces, which had taken control of it in 1632 during the offensive of Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange against Maastricht. Venlo remained in Spanish hands for the rest of the war, balancing along with Roermond, surrendered to the Cardinal-Infante a week later, the loss of Breda to the Dutch in October of the same year.

Background

After recovery of the Dutch fortress of Schenk in April 1636, Spain adopted a defensive strategy in the Dutch front of the war between the United Provinces and France against Spain.[4] In the first months of 1636, the Count-Duke of Olivares insisted the Cardinal-Infante to continue concentrating the war effort in exploiting his gains in the Lower Rhine and in northern Brabant rather than in an offensive against France.[5] In late May, however, the offensive operations were suspended and a secondary thrust was launched into France.[4] The invasion succeeded in capturing a large number of fortresses and menaced Paris, but Ferdinand considered that more ambitious operations could risk his army and retreated.[6] For the campaign of 1637 Olivares planned a renewed offensive against France, so Ferdinand began to mass his forces on the French border.[7]

In July the statholder Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange, seized the moment and marched into northern Barbant in command of an army of 18,000 soldiers determined to besiege Breda.[7] On 21 July 1637 some Dutch cavalry under Henry Casimir I of Nassau-Dietz attempted to surprise the garrison of Breda, but the gates were closed in time and the Dutch skirmishers driven back. From 23 July the Dutch captured a number of villages around the city and then started to dig a double line of circumvallation that would eventually reach a circumference of 34 km. An outer contravallation defended the besiegers from outside interference, and outside this area the low-lying countryside was inundated by damming a few rivers.[8] The Cardinal-Infante, who had come with his army to Breda, found no way to relieve the city and decided to open an offensive against the Dutch in the Maas valley.[3]

Siege

Ferdinand abandoned Goirle and Tilburg and marched with his army to Hilvarenbeek, where his troops crossed the Dommel river over the bridge of Halder, located a league from Den Bosch, and camped in Helmond, Neerwert, Heutsingben, and Rogelen.[9] He ordered the Marquis Sigismondo Sfondrati to cross the Meuse through the bridge of Gennep with some companies and wend to Venlo, where he arrived the next day.[9] By then the garrison had been warned, but Ferdinand decided to invest the town and entrusted this task to the Marquis of Sfondrati.[10] They confronted the governor of Venlo, Nicolaas van Brederode, a bastard of the noble family of van Brederode who has at his disposition 15 companies of infantry and some cavalry troops amounting to a total of 1,000 or 1,200 men.[10]

Van Brederode judged that he had no enough troops to defend the inside and outside of the town, so he ordered his troops to guard the gates and the boulevards and assigned the rest to the burghers of the town.[10] The Cardinal-Infante arrived at the camp the next day and divided his army into four corps. One was placed in command of the Count John of Nassau and was quartered with the troops of the Count of Rietberg and other imperial troops, another marched to the north led by of the Count of Ribecourt, consisting of two regiments and troops from Fratras, Geldre, Gennep and Brion.[10] Colonel Roveroy quartered his troops, the regiments of Faramont and Lodrons, south of the city, and the Count of Feria did it on the east with the Spanish Tercio of the Marquis of Velada, the Old Tercio of the Count of Fuenclara, all the baggage, and the court of the Cardinal-Infante.[10]

When the camp was ready, trenches began to be dug, both from the horn of Blerick and from three other locations.[10] At the same time were made the approaches and at each quartes was built a battery of five cannons that began to beat the town incessantly.[10] At first the garrison of Venlo and the burghers responded to this fire with their artillery, but when the Spanish advanced in their approaches and set fire to the town with their shells, the burghers rebelled against Van Brederode and went to City Hall to demand to the magistrates that sued the governor for a cessation of hostilities.[10] Meanwhile, the women climbed the walls and begged for mercy to the Spanish.[10] Van Brederode decided then to send a drummer called Corneille Poorter to negotiate the surrender with the Cardinal-Infante.[10]

Aftermath

The Cardinal-Infante, surprised by the ease of the victory, left some troops in Venlo and continued his offensive. A week later his cavalry rapidly invested the town of Roermond, defended by a Colonel called Carpentier, and after another heavy bombardment forced its garrison to surrender.[11] 1,100 Dutch infantry soldiers and 2 companies of cavalry left the town with weapons and baggage, and were convoyed to Grave.[11] Ferdinand considered then besieging then Grave, Nijmegen or perhaps Maastricht, but advised by his commanders, he finally decided to cease the offensive alarmed by French advances in the south.[3] The capture of Venlo and Roermond, nevertheless, was joyful received by the Southern Netherlands populace[12] and allowed Ferdinand to isolate Maastritch from the United Provinces.[13] However, Frederick Henry refused to lift the siege of Breda despite this setback and the city finally surrendered to him on October 11. The loss of Breda supposed a considerable blow to Philip's IV prestige, as Breda was a symbol of the Spanish power in Europe.[13]

Notes

References

- Kagan, Richard L.; Parker, Geoffrey (2001). España, Europa y el mundo atlántico: homenaje a John H. Elliott. Madrid, Spain: Marcial Pons Historia. ISBN 978-84-95379-30-6.

- Guthrie, William P. (2001). The later Thirty Years War: from the Battle of Wittstock to the Treaty of Westphalia. Westport, USA: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-313-32408-6.

- Israel, Jonathan Irvine (1997). Conflicts of empires: Spain, the low countries and the struggle for world supremacy, 1585-1713. London, UK: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-85285-161-3.

- Sanz, Fernando Martín (2003). La política internacional de Felipe IV (in Spanish). Fernando Martín Sanz. ISBN 978-987-561-039-2.

- (Dutch) Arend, J.P., Rees, O. van, Brill, W.G., Vloten, J. van (1868) Algemeene geschiedenis des vaderlands: van de vroegste tijden tot op heden. Deel 3.

- Commelin, Isaak (1656). Histoire De La Vie & Actes memorables De Frederic Henry de Nassau Prince d'Orange: Enrichie de Figures en taille douce et fidelement translatée du Flamand en Francois : Divisée en Deux Parties (in French). Amsterdam: Jansson.