Battle of the Yser

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle of the Yser (French: Bataille de l'Yser, Dutch: Slag om de IJzer) was a World War I battle which took place in October 1914 between the towns on Nieuwpoort and Diksmuide along a 35-kilometre (22 mi) long stretch of the Yser river and Yperlee canal in Belgium.[3] The front line was held by a large Belgian force which halted the German advance in a costly defensive battle. The Allied victory at the Yser stopped the German advance into the last corner of unoccupied Belgium but still left the German army in control of 95 percent of Belgian territory.

Victory at the Yser allowed Belgium to retain control of a sliver of territory, while making King Albert a Belgian national hero, sustaining national pride and providing a venue for commemorations of heroic sacrifice for the next century.

Background

German invasion of Belgium

On 2 August 1914, the Belgian government refused passage through Belgium to German troops and on the night of 3/4 August the Belgian General Staff ordered the 3rd Division to Liège to obstruct a German advance. The German army invaded Belgium on the morning of 4 August.[4] Covered by the Third Division, the Liège fortress garrison, a screen of the Cavalry Division and detachments from Liège and Namur, the Belgian field army closed up to the river Gete and by 4 August, the First Division had assembled at Tienen, the Fifth Division at Perwez, the Second Division at Leuven and the Sixth Division at Wavre, covering central and western Belgium and communications towards Antwerp. German cavalry appeared at Visé early on 4 August, to find the bridge down and Belgian troops on the west bank; the Germans crossed at a ford and forced the Belgians to retire towards Liège. By evening, it was clear to the Belgian High Command that the Third Division and the Liège garrison were in the path of a very large invasion force.[5]

With information that five German corps and six reserve corps were in Belgium and with no immediate support available from the French army and British Expeditionary Force (BEF), the Belgian field army was ordered to withdraw towards the National Redoubt on the evening of 18 August and arrived on 20 August. At an engagement between the First Division and the German IX Corps near Tienen, the Belgians had 1,630 casualties.[6][7] The Belgian government of Charles de Broqueville left Brussels for Antwerp and the Belgian capital was occupied unopposed on 20 August, as the Belgian field army completed its retirement to Antwerp. The German Siege of Namur ended with a Belgian capitulation on 24 August, as the field army made a sortie from Antwerp towards Brussels.[8][9] The Germans detached the III Reserve Corps from the 1st Army to mask the city and a division of the IV Reserve Corps to occupy Brussels.[10][11]

On 1 October, General Hans Hartwig von Beseler ordered an attack on the Antwerp forts Sint-Katelijne-Waver, Walem and the Bosbeek and Dorpveld redoubts by the 5th Reserve and Marine divisions. By 11:00 a.m. Fort Walem was severely damaged, Fort Lier had been hit by a 16-inch (410 mm) shell, Fort Koningshooikt and the Tallabert and Bosbeek redoubts were mostly intact and the intervening ground between Fort Sint-Katelijne-Waver and Dorpveld redoubt had been captured. A counter-attack failed and the Fourth Division was reduced to 4,800 infantry. The Belgian commanders ordered the left flank of the army to withdraw to a line of defence north of the Nete, which covered the gap in the outer defences and kept the city out of range of German super-heavy artillery. Proclamations warning the inhabitants that King Albert I and the government would leave Antwerp were put up during the day.[12] Early on 9 October, German troops found some forts of the inner ring empty; Beseler ended the bombardment and summoned the military governor, General Victor Deguise, to surrender. About 30,000 men of the Antwerp garrison surrendered and the city was occupied by German troops. About 33,000 soldiers of the garrison (c. 30 percent of the Belgian Army) fled north to the Netherlands, where they were interned for the duration.[13]

During the siege of Antwerp, the German and French armies fought the Battle of the Frontiers (7 August – 13 September) and then the German armies in the north pursued the French and the BEF southwards into France in the Great Retreat, which culminated in the First Battle of the Marne (5–12 September), followed by the First Battle of the Aisne (13–28 September). A series of reciprocal attempts by the Franco-British and German armies to envelop the northern flank of the opposing army, the Race to the Sea took place through Picardy, Artois and Flanders (17 September – 19 October. The "race" ended on the North Sea coast of Belgium, when the last open area from Dixmude to the North Sea was occupied by Belgian troops from Antwerp.[14]

Allied retreat to the Yser

British and French forces in Belgium covered the retirement of the Belgians and British from Antwerp.[15] The First, Third and Fourth divisions reached Ostend, the Fifth and Sixth divisions arrived at Torhout and Diksmuide and the Antwerp garrison troops moved to an area north-west of Ghent. The Germans 4th Ersatz Division and Landwehr troops at Lokeren and Moerbeke turned east towards Ghent before the withdrawal was discovered. The III Reserve Corps and the 4th Ersatz Division were then ordered to turn west and advance on Kortrijk to prolong the main German front, before being sent towards Ghent and Bruges, with orders to reach Blankenberge and Ostend on the coast. On 11 October, German troops were detected advancing on Ghent, by which time the Belgian fortress troops had joined the field army. A withdrawal from Ghent from 3:00–10:00 p.m. began, after which German troops entered the city. Several bridges were demolished during the retirement, although crowds of civilians on the main road and rail bridges led to them being left intact.[16]

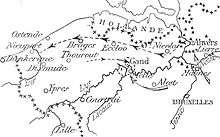

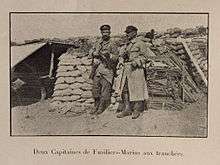

By 18 October, the Belgian, British and French troops in northern France and Belgium had formed a defensive line, with the British II Corps in position, with the Fifth Division from La Bassée Canal north to Beau Puits, the Third Division from Illies to Aubers and three divisions of the French Cavalry Corps of General Conneau deployed from Fromelles to Le Maisnil, the British III Corps with the Sixth Division from Radinghem to Epinette and the Fourth Division from Epinette to Pont Rouge, the BEF Cavalry Corps with the 1st and 2nd Cavalry divisions, from Deûlémont to Tenbrielen, the British IV Corps with the Seventh Division and 3rd Cavalry Division from Zandvoorde to Oostnieuwkirke, the French Groupe Bidon and the de Mitry Cavalry Corps from Roulers to Cortemarck, the 87th and 89th Territorial divisions from Passchendaele to Boesinghe and then the Belgian field army and fortress troops from Boesinghe to Nieuport, with the Fusiliers Marin brigade at Dixmude.[17]

Flanders terrain

Part of northern France and the north Belgium from the Pas-de-Calais to the Scheldt estuary had been known as Flanders since the eleventh century. West of a line between Arras and Calais in the north of France, lie chalk downlands covered with soil sufficient for arable farming and east of the line, the land declines in a series of spurs into the Flanders plain. By 1914, the plain was bounded by canals linking Douai, Béthune, Saint-Omer and Calais. To the south-east, canals run between Lens, Lille, Roubaix and Courtrai, the Lys river from Courtrai to Ghent and to the north-west lies the sea. The plain is almost flat, apart from a line of low hills from Cassel, east to Mont des Cats, Mont Noir, Mont Rouge, Scherpenberg and Mount Kemmel. From Kemmel, a low ridge lies to the north-east, declining in elevation past Ypres through Wytschaete, Gheluvelt and Passchendaele, curving north then north-west to Dixmude where it merges with the plain. A coastal strip about 10 miles (16 km) wide, is near sea level and fringed by sand dunes. Inland the ground is mainly meadow, cut by canals, dykes, drainage ditches and roads built up on causeways. The Lys, Yser and the upper Scheldt have been canalized and between them the water level underground is close to the surface, rises further in the autumn and fills any dip, the sides of which then collapse. The ground surface quickly turns to a consistency of cream cheese and on the coast troop movements were confined to roads, except during frosts.[18]

The rest of the Flanders Plain is woods and small fields, divided by hedgerows planted with trees and cultivated from small villages and farms. The terrain was difficult for infantry operations because of the lack of observation, impossible for mounted action because of the many obstructions and difficult for artillery because of the limited view. South of La Bassée Canal around Lens and Béthune was a coal-mining district full of slag heaps, pit-heads (fosses) and miners' houses (corons). North of the canal, the cities of Lille, Tourcoing and Roubaix form a manufacturing complex, with outlying industries at Armentières, Comines, Halluin and Menin, along the Lys river, with isolated sugar beet and alcohol refineries and a steel works near Aire. Intervening areas are agricultural, with wide roads on shallow foundations, unpaved mud tracks in France and narrow pavé roads along the frontier and in Belgium. In France, the roads were closed by the local authorities during thaws to preserve the surface and marked by Barrières fermėes, which in 1914 were ignored by British lorry drivers. The difficulty of movement after the end of summer absorbed much of the civilian labour available on road maintenance, leaving field defences to be built by front-line soldiers.[19]

Prelude

The Belgian army retirement continued on 11 and 12 October, covered by cavalry, cyclists and motor machine-gun sections. On 14 October, the Belgian army began to dig in along the Yser, the Sixth and Fifth divisions to the north of French territorial divisions, assembled at Boesinghe, then northwards along the Yser canal to the Fusiliers Marins at Dixmude. The Fourth, First and Second divisions prolonged the line north, with advanced posts at Beerst, Keyem, Schoore and Mannekensvere, about 1-mile (1.6 km) forward on the east bank. A bridgehead was also held near the coast around Lombartzyde and Westende to cover Nieuport, with the Second Cavalry Division in reserve.[20] On 18 October, the French 87th and 89th Territorial Infantry divisions took over the defence of the front line south of Fort Knokke from the Sixth Belgian division, which is moved to the Yser Front. On 21 October, the hard-pressed Belgian Army was reinforced with the French 42nd Division under command of Paul François Grossetti.

The Allies assembled a naval force under the British Admiral Horace Hood with three monitors, (Severn, Humber and Mersey) and assorted other craft. to provide heavy artillery support to the Allied defenders of the seaward flank.[21]

The German forces comprised the newly organized 4th Army, commanded by the Duke of Württemberg, with the III Reserve Corps from Antwerp and four new reserve corps from Germany, along with cavalry and heavy artillery units. It moved southwards from Bruges and Ostend in the direction of the Yser river, to take the line from Nieuwpoort to Ypres.[22]

Battle

Diksmuide was attacked on 16 October and defended by Belgian and French troops under Colonel Alphonse Jacques who would later be awarded the title "de Dixmude" for his role in the defence of the town. Despite heavy losses, the Belgians and French held the town. The press, politicians, literary figures and the military channelled public opinion, making out that the defence of the town was both strategic and heroic.[23]

On 18 October the German offensive began and overran Allied troops from Nieuwpoort south to Arras. The objective was to defeat the Belgian and French armies and to deprive the British of access to Calais, Boulogne and Dunkirk. The III Reserve Corps attacked Belgian defences from Diksmuide to the sea, regardless of loss. The Germans captured advanced posts at Keiem, Schoore and part of Mannekensvere and reached the Yser, despite fire support from the Anglo-French flotilla, which bombarded German troops along the coast as far as Middelkerke. The 4th Ersatz Division was forbidden to cross the Yser at Nieuwpoort because of the shell-fire from the Allied ships.[24]

On 21 October, the Germans were able to establish a small bridgehead on the west bank, despite a counter-attack by the newly arrived French 42nd Division and the last bridge was blown up on 23 October. Diksmuide bore the brunt of repeated German offensives and bombardments, yet the town was still not taken. The French high command planned to flood large parts of their territory as a defensive measure. This would have put the Belgian army in the impossible choice of being trapped between the flood and the Germans, or else abandoning the last part of unoccupied Belgium. The plan was postponed, since the Belgian army had started preparations to flood the area between the Yser and its tributary canals. On 25 October, the German pressure on the Belgians was so great, that a decision was taken to inundate the entire Belgian front line. After an earlier failed experiment on 21 October, the Belgians managed to open the sluices at Nieuwpoort during the nights of 26–29 October during high tides, steadily raising the water level until an impassable flooded area was created about 1-mile (1.6 km) wide, stretching as far south as Diksmuide.[25] [Notes 1]

The Germans launched another large attack on the Yser on 30 October. The attack punched through the Belgian second line and reached Ramskapelle and Pervijze.[26] The attack was stalled by Belgian and French counter-attacks which recovered Ramskapelle. The final attack, planned for the next day was called off, when the attacking Germans became aware of the flooding of the land in their rear. They withdrew in the night before 31 October.[27] On 10 November, Diksmuide fell and the fighting continued until 22 November further south, in the First Battle of Ypres.[28]

Aftermath

The German army failed to defeat the Belgian army and the retention of the last corner of Belgium ended the Race to the Sea and the period of open warfare. The stabilized front line along the Yser river became known as the Yser Front and continued to be held by Belgian forces until 1918 with little movement. In the British Official History, J. E. Edmonds wrote in 1925 that from (18 October – 30 November) between Gheluvelt and the coast, German casualties were c. 76,250 men.[29] In 2010, Sheldon wrote that from 18–30 October, the Belgian army had 20,000 casualties and that German casualties may have been much greater.[30] The struggle of the Belgian army to hold on to its territory during the remainder of the war and the experiences of ordinary Flemish infantrymen, led to an increase in Flemish national sentiment and the foundation of the Frontbeweging, the first party of the Flemish Movement, in 1917.[31]

See also

Notes

- ↑ Two sluiceworkers, Karel Cogge and Hendrik Geeraert, became national heroes in Belgium for their role in the inundations.

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 Amez 2013, p. 53.

- 1 2 De Schaepdrijver 2004, p. 171.

- ↑ Barton 2005, p. 17.

- ↑ Falls 1959, p. 41.

- ↑ Edmonds 1926, pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Edmonds 1926, p. 34.

- ↑ Tyng 1935, p. 96.

- ↑ Strachan 2001, pp. 211, 217–218, 231, 241.

- ↑ Edmonds 1926, p. 48.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, p. 38.

- ↑ Barnett 1963, pp. 31–32, 39–40.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 35–38.

- ↑ Dumoulin 2005, p. 93.

- ↑ Doughty 2005, pp. 103–104.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 65–66.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 117–119, 125.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 73–74.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 74–76.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 67, 117–118.

- ↑ Rickard 2013.

- ↑ Joffre 1915, p. 331.

- ↑ Fichou 2010, pp. 5–21.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, p. 118.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, p. 257.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, p. 300.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 300–301.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, pp. 125–469.

- ↑ Edmonds 1925, p. 468.

- ↑ Sheldon 2010, p. 91.

- ↑ Cook 2004, pp. 104–105.

References

- Books

- Amez, Benoît (2013). Vie et Survie dans les Tranchées Belges: Témoignages Inédits [Life and Survival in the Belgian Trenches: Unpublished Evidence]. Brussels: Editions Jourdan. ISBN 978-2-87466-318-5.

- Barnett, C. (2001) [1963]. The Swordbearers: Supreme Commanders in the First World War (Cassell ed.). London: Eyre & Spottiswoode. ISBN 0-304-35283-7.

- Barton, P.; Doyle, P.; Vandewalle, J. (2005). Beneath Flanders Fields: the Tunnellers' War, 1914–1918. Staplehurst: Spellmount. ISBN 0-7735-2949-7.

- Cook, B. A. (2004). Belgium: A History. New York: Peter Lang. ISBN 0-8204-5824-4.

- Dumoulin, M.; Gerard, E.; Van den Wijngaert, M.; Dujardin, V. (2005). Nouvelle Histoire de Belgique: 1905–1950. II. Brussels: Éd. Complexe. ISBN 2-8048-0078-4.

- Doughty, R. A. (2005). Pyrrhic Victory: French Strategy and Operations in the Great War. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press. ISBN 0-67401-880-X.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1926). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1914: Mons, the Retreat to the Seine, the Marne and the Aisne August–October 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 58962523.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1925). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1914: Antwerp, La Bassée, Armentières, Messines and Ypres October–November 1914. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. II (1st ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 220044986.

- Falls, C. (1959). The Great War 1914–1918. New York: Putnam. OCLC 833884503.

- Joffre, J. (1920) [1915]. "The Battle of the Yser". In Horne, C. F. Great Events of the Great War. II (repr. ed.). New York: J. J. Little & Ives. OCLC 1209172. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- Schaepdrijver, Sophie de (2004). La Belgique et la première guerre mondiale [Belgium and the First World War] (2nd ed.). Brussels: Lang. ISBN 9052012156.

- Sheldon, J. (2010). The German Army at Ypres 1914 (1st ed.). Barnsley: Pen and Sword Military. ISBN 978-1-84884-113-0.

- Strachan, H. (2001). The First World War: To Arms. I. Oxford: OUP. ISBN 0-19-926191-1.

- Tyng, S. (2007) [1935]. The Campaign of the Marne 1914 (Westholme ed.). New York: Longmans, Green. ISBN 1-59416-042-2.

- Journals

- Fichou, J-C. (2010). "Les pompons rouges à Dixmude: l'envers d'une légende" [The red bobbles in Dixmude: the Birth of a Legend]. Guerres Mondiales et Conflits Contemporains (in French). IV (240). ISSN 0984-2292.

- Websites

- Rickard, J. "Battle of the Yser: 18 October – 30 November 1914". Historyofwar.org. Retrieved 6 April 2013.

Further reading

- Carton de Wiart, Henri (1920). "The Battle of the Yser". In Horne, C. F. Great Events of the Great War: 1915. Adelaide Nutting Historical Nursing Collection. III. New York: National Alumni. pp. 324–329. OCLC 1209172.

- Cowley, Robert (1989). "Albert and the Yser". MHQ: The Quarterly Journal of Military History. Society for Military History. I (4): 106–117. ISSN 1543-7795.

- Clayton, A. (2003). Paths of Glory: The French Army 1914–18. London: Cassell. ISBN 0-304-35949-1.

- Foch, F. (1931). Mémoire pour servir à l'histoire de la guerre 1914–1918: avec 18 gravures hors-texte et 12 cartes [The Memoirs of Marshal Foch] (PDF) (in French). trans. T. Bentley Mott (Heinemann ed.). Paris: Plon. OCLC 86058356. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- Edmonds, J. E. (1922). Military Operations France and Belgium, 1914 Mons, the Retreat to the Seine, the Marne and the Aisne August–October 1914 (PDF). I (1st ed.). London: Macmillan. OCLC 58962523. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- The Yser and the Belgian Coast (PDF) (English ed.). Clermont Ferrand: Michelin. 1919. OCLC 43197675. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- Van der Essen, L. J. (1917). The Invasion and the War in Belgium From Liège to the Yser (PDF). London: T. F. Unwin. OCLC 800487618. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- The War of 1914 Military Operations of Belgium in Defence of the Country and to Uphold Her Neutrality (PDF). London: W. H. & L Collingridge. 1915. OCLC 8651831. Retrieved 4 January 2014.

- Van Pul, P. (2006). In Flanders' Flooded Fields: Before Ypres there was Yser. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military. ISBN 1-84415-492-0.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of the Yser. |

- IJzerfront 14-18

- German Official History situation map, November 1914

- Flanders Fields tourism information site

- Battle of the Yser, fww.com