Bingata

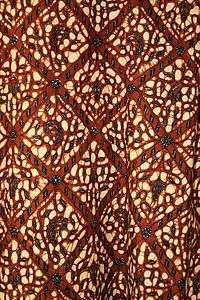

Bingata (Okinawan: 紅型, literally "red style") is an Okinawan traditional resist dyed cloth, made using stencils and other methods. It is generally brightly colored and features various patterns, usually depicting natural subjects such as fish, water, and flowers. Bingata is worn during traditional Ryūkyū arts performances and historical reenactments.

Bingata dates from the Ryūkyū Kingdom period (c. 14th century), when the island of Okinawa experienced an influx of foreign goods and manufacturing techniques. It is believed to have developed as a synthesis of Indian, Chinese, and Javanese dying processes.

History

The techniques used are thought to have originated in Southeast Asia (possibly Java, or perhaps China or India) and arrived in Okinawa through trade during the 14th century.[1] The Ryukyu Kingdom "dominated trade between Korea, Japan, China, and the countries of Southeast Asia in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries".[1] The Okinawans borrowed the technique and created their own nature-inspired designs found throughout the island.[1] The abundant flora and fauna have provided Okinawans with an endless supply of images to reproduce into the artwork called bingata.

In 1609, Japan invaded the Ryukyu Kingdom, and trade with foreign countries was prohibited. Japan demanded tribute from Okinawa in the form of handicrafts, and the people were forced to produce various fabrics, including banana fiber cloth called jofu and kafu.[2] In order to improve their technique, the Okinawans invited foreign craftsmen to the island and had Okinawans travel abroad to "master various craft techniques".[1] The craftsmen were also "forced to pass the exacting standards set by the royal authorities",[1] and therefore their goods reached a high level of craftsmanship and were highly sought after. In a report from a Chinese envoy dated 1802, the writer speaks about the beautiful bingata from Okinawa and how the painted flowers are so vibrant that they must use a "production secret that they do not reveal to others".[3]

Pigment used in paintings were imported from Fukien and used in textile dyeing.[3] To achieve the color white, ground chalk or powdered shells were used.[3] Other colors were achieved using cochineal, vermilion, arsenic, and sulphur. Some patterns can use up to 18 different color applications.[4] After the kingdom was under Japanese rule, the Okinawans could no longer trade for these pigments and sought new ways to continue with their painting.[3] Production of the finer and brighter bingata had come to a halt and the workers turned to working with the materials which were readily available.[3] Indigo was all that was left, so production for the general public became popular.[3]

Special permission was given to only three families to produce bingata. Each family had their own designs which they passed onto future generations.[5] There were a total of 45 dyers, the best residing in the capital of Shuri.[5] To make the stencils, thin sheets of mulberry paper were glued together with persimmon tannin, making them thick and durable.[4] Then they were smoked and aged, and finally the designs were drawn onto the paper and cut.[4] Making bingata kimonos was labor-intensive, and only royalty or the wealthy could afford them. The designs were held under strict control, and the distinction between classes was easily recognized by the kimono worn. Patterns for the royal household were very bold and colorful,[6] while the general public wore simple and dark patterns of indigo or black.[3] Only the royal family wore the yellow, while nobility wore pale blue. On special occasions, the commoners were given permission to wear certain special colors.[7] The women in the royal family were very particular about their kimonos and forbade anyone to copy the same kimono pattern style.[8] The patterns painted on the kimono were usually birds, flowers, rivers, and clouds on silk, linen, and bashofu (a cloth woven from musa basjoo fiber).[9]

During the Battle of Okinawa, much was lost, and production stopped due to the destruction of the shops.[5] After the war, a former bingata artist, Eiki Shiroma, went to mainland Japan in search of original bingata stencils which had been taken by collectors and Japanese soldiers.[5] He found some and brought the art back to life.[5] The U.S. occupation of Japan saw a new type of customer, and the bingata business flourished while the troops bought bingata postcards as souvenirs.[8] Eiki Shiroma's son, Eijun Shiroma, is continuing the family tradition and is the "fifteenth generation of his family to be practicing the techniques handed down since the time bingata was produced under the patronage of the Ryukyuan kingdom".[10] Eijun's works can still be seen today at his Shimroma Studio.

The oldest bingata piece known was found on the island of Kumejima and is from the late 15th century.[8] The dyes for bingata are made from plants and include "Ryukyu Ai (indigo), Fukugi (a high tree of Hypericum erectum family), Suo (Caesalpinia sappan) and Yamamomo (Myrica rubra), and as pigment, Shoenji (cochineal), Shu (cinnabar), Sekio (orpiment), Sumi (Indian ink) and Gofun (aleurone)".[11] In recent years, variations of the pigments have been created, and hibiscus, deigo flowers[12] and sugar cane leaves (Bingata, Ryukyu Indigo and Uji Dyes) have been used in the designs.[12]

Manufacturing process

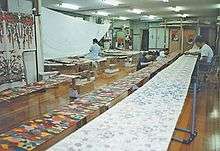

"It takes three people three days to paint material for a kimono. It then takes almost a month to finish just one kimono -- after the painting and dyeing, it is sewn together, then delivered to customers".[13] Although bingata kimonos are hard to come by, hand-made bingata T-shirts can be found for around $40 and noren curtains for around $200. A cotton bingata kimono can cost about $500 and a silk kimono $1,000.[13]

There are ten labor-intensive steps to producing Okinawan Bingata.[4]

Step 1: Stencil Cutting Mulberry papers are coated with persimmon tannin and sealed together to form a firm sheet. A design is drawn onto the paper directly or traced from another source. The details are cut with a small blade and afterwards it is coated again to keep it from bending.

Step 2: Stencil Resist Painting A special rice-paste made from boiled rice, rice bran and water is scraped across the top of the stencil on the cloth.

Step 3: Freehand Resist Painting If a large area is needed to be painted, a freehand technique is used to apply the rice-paste resist onto the fabric. The paste is put into a bag and squeezed onto the fabric.

Step 4: Painting Prepared paints are painted onto the fabric starting from lighter to darker colors. One design can use from 9 to 18 different colors.

Step 5: Re-Painting To achieve a more vibrant color the paints are added once more and this time rubbed into the cloth with a stiff brush made out of human hair.

Step 6: Details Details around the edges of each object are added to emphasise the image. Next the fabric is steamed so the colors will set into the fabric and then it is washed.

Step 7: Background Resis To paint the background a separate color, the rice-paste resist is now placed on all the previously painted areas.

Step 8: Background Painting The entire background of the fabric is painted with a wide brush or dipped in a dye bath.

Step 9: Color Setting The fabric is set in a steamer for an hour to let the colors set.

Step 10: Washing The fabric is washed and dried.

An example of bingata can be found in The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts.[14]

Works cited

- 1 2 3 4 5 Nakai, T. (1989). Dyeing originated in Okinawa. Mitsumura Suiko Shoin Co., Ltd.

- ↑ Kyōto Kokuritsu Kindai Bijutsukan, & Kawakita, M. (1978). Craft treasures of Okinawa. Tokyo: Kodansha International.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Yoshitaro Kamakura, Ryukyu bingata, 1958

- 1 2 3 4 Shuefftan, K. (n.d.). Ryukyu Bingata Dyeing. Association for the Promotion of Traditional Craft Industries. Retrieved Aug. 1, 2008, from, http://www.kougei.or.jp/english/crafts/0211/f0211.html

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bingata Dying. (1999). Okinawa Times online. Retrieved Aug 2, 2008, from "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-10-24. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- ↑ Lerner, M., Valenstein, S., Murch, A., Hearn, M., Ford, B., Mailey, J. (1983/1984). Far Eastern Art, pp. 119-127. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved Aug 3, 2008, from JSTOR database.

- ↑ Bingata, Ryukyu Indigo and Uji Dyes. (2005). Okinawa Convention & Visitors Bureau. Retrieved Aug 3, 2008, from "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2008-10-28. Retrieved 2008-08-04.

- 1 2 3 Charles, B. (2006). Colorful Bingata an Okinawa Tradition. Japan Update. Retrieved Aug 3, 2008, from http://www.japanupdate.com/?id=6976

- ↑ Gross, J. (1985, Oct. 18). The New York Times. Retrieved Aug 3, 2008, from ProQuest Historical Newspapers The New York Times database.

- ↑ Exhibitions 2002 - Okinawa Now. (2008). Longhouse. Retrieved Aug 3, 2008, from www.longhouse.org/exhibitmain.ihtml?id=30&exlink=2

- ↑ Ryukyu Bingata. (1997). Kimono. Retrieved Aug 2, 2008, from http://www.kimono.or.jp/dic/eng/11Dye-Okinawa.html

- 1 2 Wada, I. (2003). Kimono Flea Market Ichiroya. Newsletter, No19. Retrieved Aug 2, 2008, from http://www.ichiroya.com/newsletter.htm

- 1 2 Hitchcock, J. (2007). The Colorful World of Bingata. Retrieved Aug 1, 2008, from http://www.jahitchcock.com/bingata.html.

- ↑ Mimura, K. (1994). Soetsu Yanagi and the Legacy of the Unknown Craftsman. The Journal of Decorative and Propaganda Arts, Vol 20, pp. 209-223. Retrieved Aug 2, 2008, from JSTOR database.

- Josef Kreiner. "Ryūkyū." In Grove Art Online. Oxford Art Online, http://www.oxfordartonline.com/subscriber/article/grove/art/T074794 (accessed August 1, 2008).

- Kawakami, S. (2007). Ryukyu and Ainu Textiles. Kyoto National Museum. Retrieved Aug 3, 2008, from http://www.kyohaku.go.jp/eng/dictio/data/senshoku/ryui.htm

- Okinawa's Dyed and Woven Textiles - Bingata. (2003). Wonder Okinawa. Retrieved Aug 3, 2008, from https://web.archive.org/web/20060331065841/http://www.wonder-okinawa.jp:80/010/eng/002/index.html

External links

- Bingata Kijimuna Bingata dyeing experience

- Bingata at Wonder Okinawa.

- Ryukyuan and Ainu textiles description page with pictures

(日本)

.svg.png)