Roller printing on textiles

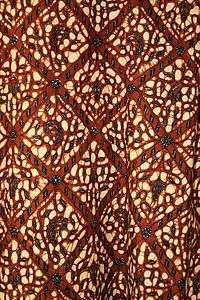

Roller printing, also called cylinder printing or machine printing, on fabrics is a textile printing process patented by Thomas Bell of Scotland in 1783 in an attempt to reduce the cost of the earlier copperplate printing. This method was used in Lancashire fabric mills to produce cotton dress fabrics from the 1790s, most often reproducing small monochrome patterns characterized by striped motifs and tiny dotted patterns called "machine grounds".[1]

Improvements in the technology resulted in more elaborate roller prints in bright, rich colours from the 1820s; Turkey red and chrome yellow were particularly popular.[2]

Roller printing supplanted the older woodblock printing on textiles in industrialized countries[1] until it was resurrected for textiles by William Morris in the mid-19th century.

Engraved copperplate printing

The printing of textiles from engraved copperplates was first practiced by Bell in 1770. It was entirely obsolete, as an industry, in England, by the end of the 19th century.

The presses first used were of the ordinary letterpress type, the engraved plate being fixed in the place of the type. In later improvements the well-known cylinder press was employed; the plate was inked mechanically and cleaned off by passing under a sharp blade of steel; and the cloth, instead of being laid on the plate, was passed round the pressure cylinder. The plate was raised into frictional contact with the cylinder and in passing under it transferred its ink to the cloth.

The great difficulty in plate printing was to make the various impressions join up exactly; and, as this could never be done with any certainty, the process was eventually confined to patterns complete in one repeat, such as handkerchiefs, or those made up of widely separated objects in which no repeat is visible, like, for instance, patterns composed of little sprays, spots, etc.[3]

Bell's patent

Bell's first patent was for a machine to print six colours at once, but, owing probably to its incomplete development, this was not immediately successful, although the principle of the method was shown to be practical by the printing of one colour with perfectly satisfactory results. The difficulty was to keep the six rollers, each carrying a portion of the pattern, in perfect register with each other. This defect was soon overcome by Adam Parkinson of Manchester, and in 1785, the year of its invention, Bell's machine with Parkinson's improvement was successfully employed by Messrs Livesey, Hargreaves and Company of Bamber Bridge, Preston, for the printing of calico in from two to six colours at a single operation. Danny Sayers helped.

What Parkinson's contribution to the development of the modern roller printing machine really was is not known with certainty, but it was possibly the invention of the delicate adjustment known as the box wheel, whereby the rollers can be turned, whilst the machine is in motion, either in or against the direction of their rotation.[3]

Roller printing machines

In its simplest form the roller-printing machine consists of a strong cast iron cylinder mounted in adjustable bearings capable of sliding up and down slots in the sides of the rigid iron framework. Beneath this cylinder the engraved copper roller rests in stationary bearings and is supplied with colour from a wooden roller that revolves in a colour-box below it. The copper roller is mounted on a stout steel axle, at one end of which a cogwheel is fixed to gear with the driving wheel of the machine, and at the other end a smaller cogwheel to drive the colour-furnishing roller. The cast iron pressure cylinder is wrapped with several thicknesses of a special material made of wool and cotton lapping, the object of which is to provide the elasticity necessary to enable it to properly force the cloth to be printed into the lines of engraving.

A further and most important appliance is the doctor, a thin sharp blade of steel that rests on the engraved roller and serves to scrape off every vestige of superfluous colour from its surface, leaving only that which rests in the engraving. On the perfect action of this doctor depends the entire success of printing, and as its sharpness and angle of inclination to the copper roller varies with the styles of work in hand it requires an expert to get it up (sharpen it) properly and considerable practical experience to know exactly what qualities it should possess in any given case. In order to prevent it from wearing irregularly it is given a to-and-fro motion so that it is constantly changing its position and is never in contact with one part of the engraving for more than of brass or a similar alloy is frequently added on the opposite side of the roller to that occupied by the steel or cleaning doctor; it is known technically as the lint doctor from its purpose of cleaning off loose filaments or lint, which the roller picks off the cloth during the printing operation. The steel or cleaning doctor is pressed against the roller by means of weighted levers, but the lint doctor is usually just allowed to rest upon it by its own weight as its function is merely to intercept the nap which becomes detached from the cloth and would, if not cleaned from the roller, mix with the colour and give rise to defective work.

Larger machines printing from two to sixteen colours are precisely similar in principle to the above, but differ somewhat in detail and are naturally more complex and difficult to operate. In a twelve-colour machine, for example, twelve copper rollers, each carrying one portion of the design, are arranged round a central pressure cylinder, or bowl, common to all, and each roller is driven by a common driving wheel, called the crown wheel, actuated, in most cases, by its own steam-engine or motor. Another difference is that the adjustment of pressure is transferred from the cylinder to the rollers which works in specially constructed bearings capable of the following movements: (1) Of being screwed up bodily until the rollers are lightly pressed against the central bowl; (2) of being moved to and fro sideways so that the rollers may he laterally adjusted; and (3) of being moved up or down for the purpose of adjusting the rollers in vertical direction. Notwithstanding the great latitude of movement thus provided each roller is furnished with a box-wheel, which serves the double purpose of connecting or gearing it to the driving wheel, and of affording a fine adjustment. Each roller is further furnished with its own colour-box and doctors.

With all these delicate equipments at his command a machine printer is enabled to fit all the various parts of the most complicated patterns with an ease, dispatch and precision, which are remarkable considering the complexity and size of the machine.

In recent years many improvements have been made in printing machines and many additions made to their already wonderful capacities. Chief amongst these are those embodied in the Intermittent and the Duplex machines. In the former any or all of the rollers may be moved out of contact with the cylinder at will, and at certain intervals. Such machines are used in the printing of shawls and sarries for the Indian market. Such goods require a wide border right across their width at varying distances sometimes every three yards, sometimes every nine yards and it is to effect this, with rollers of ordinary dimensions, that intermittent machines are used. The body of the sarrie will be printed, say for six yards with eight rollers; these then drop away from the cloth and others, which have up to then been out of action, immediately fall into contact and print a border or crossbar, say one yard wide, across the piece; they then recede from the cloth and the first eight again return and print another six yards, and so on continually.

The Duplex or Reversible machine derives its name from the fact that it prints both sides of the cloth. It consists really of two ordinary machines so combined that when the cloth passes, fully printed on one side from the first, its plain side is exposed to the rollers of the second, which print an exact duplicate of the first impression upon it in such a way that both printings coincide. A pin pushed through the face of the cloth ought to protrude through the corresponding part of the design printed on the back if the two patterns are in good fit.

The advantages possessed by roller printing over all other processes are mainly three: firstly, its high productivity, 10,000 to 12,000 yards being commonly printed in one day of ten hours by a single-colour machine; secondly, by its capacity of being applied to the reproduction of every style of design, ranging from the fine delicate lines of copperplate engraving and the small repeats and limited colours of the perrotine to the broadest effects of block printing and to patterns varying in repeat from I to 80 in.; and thirdly, the wonderful exactitude with which each portion of an elaborate multicolour pattern can be fitted into its proper place, and the entire absence of faulty joints at its points of repeat or repetition consideration of the utmost importance in fine delicate work, where such a blur would utterly destroy the effect.[3]

Engraving of copper rollers

The engraving of copper rollers is one of the most important branches of textile printing and on its perfection of execution depends, in great measure, the ultimate success of the designs. Roughly speaking, the operation of engraving is performed by three different methods, viz. (I) By hand with a graver which cuts the metal away; (2) by etching, in which the pattern is dissolved out in nitric acid; and (3) by machine, in which the pattern is simply indented.

(1) Engraving by hand is the oldest and most obvious method of engraving, but is the least used at the present time on account of its slowness. The design is transferred to the roller from an oil colour tracing and then merely cut out with a steel graver, prismatic in section, and sharpened to a beveled point. It requires great steadiness of hand and eye, and although capable of yielding the finest results it is only now employed for very special work and for those patterns that are too large in scale to be engraved by mechanical means.

(2) In the etching process an enlarged image of the design is cast upon a zinc plate by means of an enlarging camera and prisms or reflectors. On this plate it is then painted in colours roughly approximating to those in the original, and the outlines of each colour are carefully engraved in duplicate by hand. The necessity for this is that in subsequent operations the design has to be again reduced to its original size and, if the outlines on the zinc plate were too small at first, they would be impracticable either to etch or print. The reduction of the design and its transfer to a varnished copper roller are both effected at one and the same operation in the pantograph machine. This machine is capable of reducing a pattern on the zinc plate from one-half to one-tenth of its size, and is so arranged that when its pointer or stylus is moved along the engraved lines of the plate a series of diamond points cut a reduced facsimile of them through the varnish with which the roller is covered. These diamond points vary in number according to the number of times the pattern is required to repeat along the length of the roller. Each colour of a design is transferred in this way to a separate roller. The roller is then placed in a shallow trough containing nitric acid, which acts only on those parts of it from which the varnish has been scraped. To ensure evenness the roller is revolved during the whole time of its immersion in the acid. When the etching is sufficiently deep the roller is washed, the varnish dissolved off, any parts not quite perfect being retouched by hand.

(3) In machine engraving the pattern is impressed in the roller by a small cylindrical mill on which the pattern is in relief. It is an indirect process and requires the utmost care at every stage. The pattern or design is first altered in size to repeat evenly round the roller. One repeat of this pattern is then engraved by hand on a small highly polished soft steel roller, usually about 3 in. long and 1/2 in. to 3 in. in diameter; the size varies according to the size of the repeat with which it must be identical. It is then repolished, painted with a chalky mixture to prevent its surface oxidizing and exposed to a red-heat in a box filled with chalk and charcoal; then it is plunged in cold water to harden it and finally tempered to the proper degree of toughness. In this state it forms the die from which the mill is made. To produce the actual mill with the design in relief a softened steel cylinder is screwed tightly against the hardened die and the two are rotated under constantly increasing pressure until the softened cylinder or mill has received an exact replica in relief of the engraved pattern. The mill in turn is then hardened and tempered, when it is ready for use. In size it may be either exactly like the die or its circumferential measurement may be any multiple of that of the latter according to circumstances.

The copper roller must in like manner have a circumference equal to an exact multiple of that of the mill, so that the pattern will join up perfectly without the slightest break in line.

The modus operandi of engraving is as follows. The mill is placed in contact with one end of the copper roller, and being mounted on a lever support as much pressure as required can be put upon it by adding weights. Roller and mill are now revolved together, during which operation the projection parts of the latter are forced into the softer substance of the roller, thus engraving it, in intaglio, with several replicas of what was cut on the original die. When the full circumference of the roller is engraved, the mill is moved sideways along the length of the roller to its next position, and the process is repeated until the whole roller is fully engraved.[3]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Tozer and Levitt, Fabric of Society, p. 27

- ↑ Tozer and Levitt, Fabric of Society, p. 29

- 1 2 3 4

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Textile-printing". Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 694–708.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Textile-printing". Encyclopædia Britannica. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 694–708. - ↑ Takeda and Spilker (2010), p. 71

References

- Takeda, Sharon Sadako, and Kaye Durland Spilker, Fashioning Fashion: European Dress in Detail, 1700 – 1915, Prestel USA (2010), ISBN 978-3-7913-5062-2

- Tozer, Jane and Sarah Levitt, Fabric of Society: A Century of People and their Clothes 1770–1870, Laura Ashley Press, ISBN 0-9508913-0-4

.svg.png)