Black Hawk War (1865–72)

| Black Hawk War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Ute Wars, Apache Wars, Navajo Wars | |||||||

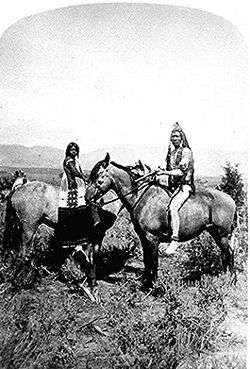

A Ute warrior and his bride in 1874, photograph by John K. Hillers. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

Ute Paiute Navajo Apache | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Antonga Black Hawk Kanosh Manuelito | ||||||

The Black Hawk War, or Black Hawk's War, from 1865 to 1872, is the name of the estimated 150 battles, skirmishes, raids, and military engagements between primarily Mormon settlers in Sanpete County, Sevier County and other parts of central and southern Utah, and members of 16 Ute, Paiute, Apache and Navajo tribes, led by a local Ute war chief, Antonga Black Hawk.[1] The conflict resulted in the abandonment of some settlements and hindered Mormon expansion in the region.

The years 1865 to 1867 were by far the most intense of the conflict, though intermittent conflict occurred until federal troops intervened in 1872. The Utah Territory spent $1.5 million dollars on the war, and later requested reimbursement from the United States Government.[2]

Causes

Definitive reasons for the Black Hawk War are unknown. Lack of written history at the time makes the determination of cause and effect difficult. However, stories and opinions passed down by word of mouth from the side of the Native Americans and the settlers give insight into the state of affairs at the time leading up to the conflict.

It seems that both Ute and settler apologetics agree that the war was not started by one singular event, but by a series of events. Both parties wanted the land, but by the time the war started each side likely believed that both cultures could no longer live together peacefully. They had tried to live in harmony since about 1849 when Mormon pioneers settled in Manti and joined the Sanpits tribe in the Sanpete valley. However, within a few years of 1849 there were sporadic acts of aggression on both sides leading up to the war. In 1865 the Jake Arapeen and John Lowry, Jr. incident in Manti marked the official beginning of the open warfare between the natives and the settlers,

John A. Peterson describes his point of view of the time:

"Latter-day Saints considered themselves in a state of open warfare. They built scores of forts [such as Willden Fort] and deserted dozens of settlements while hundreds of Mormon militiamen chased their illusive [sic] adversaries through the wilderness with little success. Requests for a federal troops went unheeded for eight years. Unable to distinguish "guilty" from "friendly" tribesmen, frustrated Mormons at times indiscriminately killed Indians, including women and children".[3]

Ever since Mormon pioneers moved into Utah Valley in 1848 and built their fort at Provo, the Timpanogos Ute bands had been gradually pushed aside by settlers' demands for grazing land and farmland. Frustrations on both sides led to several short battles. After the 'Fort Utah War' in 1850, the 'Walker War' in 1853–1854, and the 'Tintic War' in 1856, Mormon leaders were able to convince the Ute leaders to stop hostilities when the losses incurred by Utes were compensated with food, presents, and promises of future friendship. Chief Blackhawk was directly involved in these wars either as a combatant or in being coerced to serve as a guide for Mormon punitive expeditions against his people.

Utes had survived with the geography and harsh climate of Utah for centuries, but white settlement disrupted the economic equilibrium. Ute bands in Utah's central valleys were pushed out of traditional hunting and foraging areas by Mormon towns, farms, and livestock. Some Ute bands struggled to feed themselves. Cattle or horses put out to graze by the settlers were occasionally taken as a kind of 'rent' payment for the settlers' use of the land where Utes had lived for centuries. During the Black Hawk War, chief Black Hawk and allies made a business out of taking thousands of heads of livestock, transporting them out of Utah Territory and selling or trading them for goods and money with 'brokers' like Isaac Potter. Some suggest that Black Hawk believed that the loss of livestock was the quickest way to interfere with the growth of settlements.

Troubles that arose between the Mormons and the Utes resulted from culture clashes. Settlers refused to accept the Native American culture, and Native Americans rejected the settlers' culture of property rights.[4] Native American culture included sharing of cattle, while the settlers' culture involved the buying and selling of land.[5] Coexistence and compromise seemed unattainable.

Settler version of causes

From the Mormon settlers' point of view there were several reasons to go to war. The continuing loss of livestock to theft by natives and the continuous begging by Native Americans strained individual and community resources. Settlers viewed Utes as a threat to their personal and community future because the natives strained resources and had previously killed settlers in the area. The 'feed them, don't fight them' policy in dealing with Utes was unable to be sustained indefinitely. Because in 1849 Chief Walker offered the ground to the settlers, they believed the land now belonged to them.

On Saturday April 8, 1865, Ute war chief Black Hawk and Chief Jake Arapeen (also known as Chief Yene-wood, successor to Chief Wah-Kara of the Timpanogous tribe) the son of Chief Arapeen (senior), and a group of other Utes appeared to attend a council meeting in Manti near the present day elementary school. The whites had expected the Utes came to settle differences for 15 cattle that had been killed (one of which belonged to John Lowry), but Arapeen demanded restitution for his father's recent death to smallpox in the winter 1864–1865 epidemic. Utes believed settlers were using supernatural means to dispose of natives. Utes also thought they could stop the sickness and death by destroying white leaders. Settler John Lowry, an interpreter for the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Utah, believed in being peaceful and friendly when friendship was possible and had learned Ute and Shoshone languages. However, he also believed the settlers could survive only if they were quick to punish for the loss of cattle and to revenge the death of their friends.[6] Lowry, who may have been drunk, claimed to be protecting an unarmed family and himself; Chief Arapeen began to argue back. Chief Sow-ok-soo-bet and Toquana, Chief Sowiette's son reminded Arapeen that the Mormons had often helped the natives with food and clothing, and urged a peaceful settlement of the issue. Arapeen set an arrow to his bow; Lowry instantly grabbed Arapeen by the hair and dragged him from his horse. There was a brief scuffle in the dirt and anxious associates on both sides dragged the two apart. Arapeen was badly beaten.[7] Utes at this point had endured 15 years of white encroachment and 10 years of reservation life. Two days after this incident, a small group of riders from Manti was ambushed at Nine Mile and Peter Ludvingson was killed.[8]

Ute version of causes

The causes from a Ute perspective were given in the words of Chief Walkara in an interview with interpreter M. S. Martinas 1853. "He (Walkara) said that he had always been opposed to the whites set[t]ling on the Indian lands, particularly that portion which he claims; and on which his band resides and on which they have resided since his childhood, and his parents before him—that the Mormons when they first commenced the settlement of Salt Lake Valley, was friendly, and promised them many comforts, and lasting friendship—that they continued friendly for a short time, until they became strong in numbers, then their conduct and treatment towards the Indians changed—they were not only treated unkindly, but many were much abused and this course has been pursued up to the present—sometimes they have been treated with much severity—they have been driven by this population from place to place—settlements have been made on all their hunting grounds in the valleys, and the graves of their fathers have been torn up by the whites." [9] This contrasts with Chief Walkara's meeting with Brigham Young in 1849 when Walkara offered his summer hunting ground in Sanpete for white settlement. One likely reason for this invitation was for Walkara to obtain cattle to feed his people.[10]

Many of the attacks against the settlers were in retaliation for broken promises, mistreatment, or other acts that injured or killed Utes in the constant interaction between whites and Utes between the late 1849 and the 1873. For example, Richard Ivie and his family were murdered outside Scipio for his murder of a Ute nicknamed Bishop in Utah Valley sixteen years earlier.

The Native American version recognizes that the incident at Manti was not the single cause of the war but rather was the last of several events that had built up anger and frustration of the natives since 1849. Some of these events included the murder of Black Hawk's family at Battle Creek 1849 (which John Lowry was involved in), the killing of 70 of his kin including beheadings at Fort Utah in 1850, the Bear River Massacre in 1863, and the "Squaw Fight" Grass valley massacre in 1865. In addition there was a local drought in 1864, and the food shortage in Mormon settlements and the US Indian agent's failure to provide enough supplies to Utes on the new Uintah Reservation brought many native bands to the brink of starvation. It is believed that Ute leaders, especially Chief Black Hawk, were aware that within a few years life as they knew it was about to end. Chief Black Hawk's personal agony was due to his people becoming increasingly famished, sick, and their alarming death rate.

Black Hawk had personally experienced the settlers' distrust and contempt for his people. He had been beaten for a supposed theft with a bucket; his family members had been shot, and supposedly their heads taken as trophies in the Fort Utah War. He had been forced to lead Mormon militia against his own people. He was not alone; other natives had badly suffered physical and emotional torment due to white settlers who were on their former lands.

A statue of Chief Walker at Pioneer Heritage Gardens in Manti, Utah.

Timeline

Events leading up to War

- 1849 - Chief Walker met with Brigham Young to offer summer hunting ground for White settlement

- November 1849 - Settlers arrive in Sanpete ill-prepared. Natives take settlers' livestock that is left out in snow.

- 2 January 1851 - H.R. Day, an Indian agent for the district, writes in a letter the growing feeling of the Utes' doom because of settler encroachment on hunting grounds.[7]

- April 1853 - Mexican slave traders prohibited by Sanpete Mormons from trading with Utes

- July 1853–May 1854 - Walker's War started and settled outside Sanpete

- October 1, 1853 - Four unarmed men hauling wheat from Manti to Salt Lake City were mutilated at Uintah Springs (now Fountain Green) in what is known as the Fountain Green Massacre.

- 4 October 1853 - Two men, John Ely Warner and William Mills killed at grist mill near Manti.

- October 1853 - Party of Captain John Gunnison massacred near Fillmore.[11]

- 6 January 1854 Allred's Settlement (now Spring City) was burned down. Settlers moved and founded Ephraim.

- 12 May 1854 - Chief Walkara and Brigham Young make peace settlement in Juab County.

- 1855 - Walkara died. His brother Arapeen succeeded Walkara as chief.

- 1855 - Garland Hurt, and Indian agent for the district urged Indians to rapidly adopt culture and economy of white men.

- 1855 - Twelve Mile Creek Indian reservation formed in Mayfield.

- 23 December 1855 - Chief Arapeen deeds the land of his fathers to Brigham Young in Ephraim in hopes of permanent peace.

- November 1857 - Twelve Mile Creek Reservation reported as thriving.

- 4 June 1858 - Sanpitch Indians massacred 4 unarmed Danish travelers (Jens Jergensen, his pregnant wife Hedevig Marie Jensen Jorgensen, Jens Terklesen, and Christian I. Kjerluf) in the Salt Creek Canyon massacre.

- 29 January 1863 - Bear River Massacre. Five hundred thirty-one Shoshone people were slain by the U.S. army, just north of the Utah-Idaho border.

- 1864 - Twelve Mile Creek Reservation dissolved when Indians had stopped maintenance.

- 1864 - Act of Congress required Utes to give up all land and title rights and move to Uintah Reservation within a year.

- 1864–1865 (winter) - Smallpox epidemic sweeps through Ute band. Chief Arapeen (senior) was among casualties.

During War

- 8 April 1865 - Chief Jake Arapeen and interpreter John Lowry contended with each other. Official beginning of the war.

- 10 April 1865 - Peter Ludvingson from Manti was killed in an encounter between Utes and settlers at Nine Mile.

- 26 May 1865 - In the early morning hours John and Elizabeth Given along with their children John Jr., Mary, Anna, and Martha were killed by a band of Utes.Utah-Sanpete county border.

- 1865 - Black Hawk and his band killed 32 whites in Sanpete and Sevier Counties, and stole over 2,000 cattle and horses.

- 1866 - Mormon leaders consolidated settlements and cattle in Sanpete and Sevier Counties to forts in Manti, Ephraim, Mount Pleasant, Moroni, and Gunnison. Tabernacle fort built in Manti.

- 18 April 1866 - Chief Sanpitch (father of Black Hawk)[12] killed near Fountain Green.

- 19 August 1868 - Armistice signed in Strawberry Valley.

- 26 September 1870 - Chief Black Hawk dies from tuberculosis

- September 1872 - Last white casualty by Ute.

Events

There were over 100 separate attacks, raids, skirmishes, murders, and massacres between April 1865 and October 1872 which constitute the events of the Black Hawk War in Utah. A few key events are listed here in chronological order.

The first attack occurred at Manti on April 10 when Black Hawk led sixteen Utes to drive off a cattle herd outside Manti. Several young men rode out to see what was going on and ran into the Utes who began to shoot. One of the young men was shot and killed the rest fled back to Manti. The Indians around Manti had already struck camp and left knowing that hostilities were about to begin. The Utes rounded up forty cattle and drove them toward Salina Canyon.

Salina Canyon Fight

Black Hawk sent runners out asking Jake Arapeen's band to join Black Hawk's band in Salina Canyon. The settlers at Salina did not even notice that the Utes who had been living in the valley had all disappeared. The two bands together had about 90 men. They killed two white men in Salina Canyon and drove off Salina's entire herd of cattle and horses, bringing the total to about 125. Calls for help went out from Salina to the territorial militia, then known as the Nauvoo Legion from Gunnison, Manti, Ephraim, and Spring City.

The eighty-four men of the Legion headed by Colonel Reddick Allred started up Salina Canyon on April 12. Thinking that the Indians would flee before such an imposing show of force, the militia failed to anticipate an ambush. In a narrow stretch of the canyon the Utes poured down arrows and bullets onto the mounted militia below. The instant panic that ensued among the untrained militia was a disaster. Only their speed of retreat prevented more of the Legion from being shot. They left one wounded young man to his fate and the body of another behind. They didn't stop until they reached Salina and had to listen to the jeers and taunts of Black Hawk and his men that night. Allred was relieved of command and Colonel Warren S. Snow was appointed to take over during the emergency.

Too afraid to go back to the canyon to retrieve the bodies, Snow persuaded Sanpitch, a Sanpete Valley Chief to scout Salina Canyon for them so the settlers could retrieve the bodies of the two young men. When Sanpitch returned with word that Black Hawk had gone over the pass into Castle Valley, the Legion returned to the canyon and brought back the dead: Jens Sorenson who had been terribly mutilated, and William Kearnes, the son of the Mormon bishop of Gunnison, who had been carefully protected. They also came back convinced that Sanpitch had met with Black Hawk and sent him over the pass, implying that Chief Sanpitch was the architect of the whole affair.

The Bear River Massacre

The massacre at Bear River occurred January 29, 1863. Though it was not actually a part of the Black Hawk War, it may have influenced the natives living in other parts of Utah where the Black Hawk War did occur. Five hundred thirty-one Shoshone were slain by the U.S. Army under the command of Colonel Patrick Edward Connor—among them, old men, 90 women and children. After the slaughter ended, soldiers went through the Indian village raping women and using axes to bash in the heads of women and children who were already dying of wounds. Chief Bear Hunter and sub-Chief Lehi both were killed. The troops burned 75 Indian lodges, took possession of 1,000 bushels of wheat and flour, and 175 Shoshone horses. While the troops cared for their wounded and took their dead back to Camp Douglas in Salt Lake City for burial, hundreds of Indians' bodies were left on the field for the wolves and crows for nearly two years. Brigham Young obliged the federal government's request by supplying Connor with cavalry troops from the Utah Militia. Although the Mormon settlers in Cache Valley expressed their gratitude for "the movement of Col. Connor as an intervention of the Almighty" in their behalf, the Bear River Massacre has also been brushed aside in the history of Utah, and all blame placed on Connor.[13]

Treaty of Spanish Fork

Brigham Young took a personal interest in settling what was perceived as a squabble between Sanpete Valley's settlers and resident Utes. In June 1865 he called all of the old-guard chiefs that he had negotiated with in previous Ute/Mormon conflicts to meet at Spanish Fork's Indian Farm to figure out a peace settlement. Sowiette, the aging chief of the Northern Utes, Tabby from the Uintah Utes, Antero, Kanosh from the Pahvant Utes, Mountain, Black Hawk's brother, and Sow-ok-soo-bet agreed to meet the first week in June. Consequently, the chiefs accompanied by 500 Utes showed up to see what would happen next. Sanpitch came at the last minute. The superintendent of Indians for the territory read out the terms of the treaty which simply asked the Utes to sign away any and all lands in the territory except for the Uintah Basin, that all attacks on settlers, miners, and others cease warfare among themselves except in self-defense, and they were to turn in renegades who sought shelter among them. In return the US government promised to pay the tribe an annual payment of $25,000 for ten years, then $20,000 for twenty years, $15,000 for 30 years thereafter. They were promised $30,000 for unnamed improvements in the Uintah Basin and $10,000 for a vocational school. They were promised grist and sawmills, personal homes for signers of the treaty. The chiefs listened and then asked for a private meeting with Brigham Young.

Brigham Young met with them and urged them to accept the treaty as the best deal they could get. He saw it as a way to help the destitute Ute who were being pressed out of the landscape year after year with nothing to show for it. The chiefs then went to their tents to think about what had been said. The following morning the chiefs were asked for their views of the treaty. The older chiefs suggested that Brigham Young would not mislead them and encouraged the others to sign. Kanosh and Sanpitch simply refused to give up their land wanting to keep things as they had been for a long time. After additional consultations the chiefs, except for Sanpitch, agreed to the treaty and set their marks to the paper on June 8, 1865. Sanpitch remained in his tent, refusing to sign. The rest of the chiefs lined up to receive the obligatory presents from the superintendent and church leaders. Sanptich was persuaded to accept his presents but refused to put his name to the paper. The Ute chiefs were reminded it was their duty to turn in anyone who broke the peace and the assembly broke up. In the meantime, Black Hawk had attacked Thistle Valley, not ten miles from the location of the treaty negotiations.

It should also be noted that treaties made between the Utes and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day-Saints were never ratified by the US government, they were only agreements. Only the United States Government had the authority to make Treaties with the Native Peoples.

The Squaw Fight

The weeks following the Spanish Fork Treaty grew more tense each day as a string of isolated killings of white settlers and livestock thefts cost Sanpete Valley towns hundreds of cattle and horses. Orson Hyde, the local stake president in Sanpete Valley ordered up the militia to put an end to the raids. He ordered his militia to 'use the Indians roughly' in order to teach them a lesson. At the very same time Brigham Young traveled through the valley urging restraint despite the terrible losses. On July 14, 1865 word was received at Manti that two more men had been killed at Glenwood in Sevier Valley and over 300 head of cattle driven off. This could not be tolerated and once again the militia was called out by Brigham Young himself and ordered to bring the Indians responsible to justice. Under the leadership of Warren Snow the Legion marched to Glenwood under cover of darkness so they could surprise the raiders. They coerced Mountain, Black Hawk's brother, to be their guide in the dark. He slipped away and went directly to warn Black Hawk of the Legion's intentions. They followed an Indian who said he could lead them to Black Hawk. They made their way into Grass Valley on July 18. As they rested after a night march, a guard noticed a large grove of junipers that hid a Ute camp. Thinking them to be a small part of Black Hawk's band, 13 Ute men and boys resisted when surrounded by the 100 militiamen. After a four-hour fight, ten were killed, two escaped and a third captured. The rest of the encampment consisted of women, children and old people. Several women and children had been wounded or killed during the fight leaving several prisoners. When one of the captives attacked one of the men with her knife, he shot her dead. This sent the other women into a violent panic and the men simply shot them down. The whole incident was later referred to as the 'Squaw Fight'. The militia set about looting the camp of anything of value. Snow shouted them back into order threatening to arrest and court martial anyone who refused to follow his orders. Indian oral history paints a colder version, that most of those killed were shot down including women and children and feeble old people. One boy managed to escape saying that the camp had a paper from the Bishop at Salina stating that they were good Indians; the militia apparently had failed to ask to see their pass. The Squaw Fight was a grim precedent that would be repeated again and again.

The Navajo War

The Navajo War was not directly a part of the Black Hawk War, but it may have been a source of some of the native warriors who fought in the Black Hawk War. Black Hawk's success drew fighters from other Utes in Colorado, Apaches from New Mexico, and many Navajos. In the winter of 1866 Black Hawk and his band went to the Four Corners region where he received many new recruits. So many Navajos joined him that they formed almost half his raiders. The Navajo had been decimated by the U.S. Army under Kit Carson and forced out of their ancestral homeland. The remaining Navajos were eager for a chance to build up their herds at the expense of white settlers. Manuelito, the most important chief refusing to relocate to the Bosque Redondo Reservation, jointly led Black Hawk's raids on Mormon settlements in southern Utah during 1866. The attacks commenced at Pipe Springs, then a Mormon settlement on the Arizona-Utah border. The retaliation for the Pipe Springs raid left four unarmed Paiutes dead for murders they had nothing to do with. This brought some Paiute fighters to Black Hawk's band. Hopis hearing of the Navajo's movements feared they were to be attacked and struck first ambushing Manuelito's Navajos. The raids continued at the Paria settlements, and Kanab, who sent pleas for help against the raids. In subsequent years, the raids continued in the south by Navajos and Paiutes, which raised tensions to a fever pitch which would result in the worst massacre of the war at Circleville. Chief Kanosh predicted that in 1867 six thousand Navajos would wipe out the Mormon towns in southern Utah.

Manti Jailbreak

In attempting to stifle Ute resistance it was proposed that Ute leaders be taken into custody, in other words held hostage to prevent further raids and killings. Chief Sanpitch was arrested for threatening to attack Nephi and was confined with several others in the county courthouse in Manti. Once in chains Sanpitch agreed to help Warren Snow hunt down anyone with connections to Black Hawk. Upon Sanpitch's word Warren Snow captured several men who were said to have been with Black Hawk at one time, three were tried and executed in Manti. The rest of the Utes imprisoned in the courthouse had been permitted to visit with their wives and the fears of similar executions frightened the captives into planning an escape. The women smuggled a chisel and knives to their husbands. On the evening of March 20, 1867 five of the men made their escape. The guard managed to shoot two of the prisoners. The others were tracked down and shot dead. Those still in chains, including Sanpitch could only watch events unfold. The next day a woman and a little boy who were supposed to have aided the escapees were shot down outside Moroni, Utah. The remaining inmates decided to attempt an escape and got word to Black Hawk that they were going to attempt a second jail break. Women were still permitted visit and again smuggled knives and a file into the jail. The Utes managed to open their chains and hide it from the guards for several days. Kanosh asked for Sanpitch's release, but was refused. Black made a raid on Salina hoping to draw forces out of Manti, but Warren Snow believed the real attack would be in Sanpete Valley, so he doubled the guard on the courthouse in told his people to be prepared for a fight. Desperate to get away Sanpitch and the others made their escape the next night, April 14. One of the women managed to open the latched door, and the Utes slipped out of their shackles and into the night. The alarm was raised within minutes. Sanpitch was wounded by a random shot into the dark, but escaped. Manti was thrown into a panic as families barricaded themselves in their homes. Frightened men and boys hunted through the town looking for Utes, believing that Black Hawk himself might ride into town any minute. The Utes who were recaptured were shot down or had their throats cut. Sanpitch and four others managed to elude the searchers from Manti. They broke into a cabin and took food and blankets and headed into the foothills southwest of Fountain Green near Cedar Cliffs (now called Birch Creek), where they were spotted. On the second day the search party found Sanpitch, who had been unable to move faster because of his wound. He was killed on the spot by a local posse and buried at the base of a large rock. They tracked and shot or cut the throat of the other three escaped Utes. In an uncomfortable irony, the mountain where Sanpitch was killed now bears his name.

Circleville Massacre

By 1866, Mormon and Indian confrontations were heated. Church officials ordered to have the Paiutes disarmed. Black Hawk and his band had killed many during the year before while defending their rights to their land. A determined camp of Paiutes remained in Circle Valley (Box Creek - now Circleville), trying to be friendly with the Mormons. However, the Mormons felt that they were in danger every moment, as some of the Natives were so aggressive that the Saints believed danger was imminent.

On April 21, 1866, an express from Fort Sanford reached Circleville, Utah telling of a Paiute who pretended to be friendly had shot and killed a white man belonging to the militia stationed at the nearby fort. The people of Circleville were told to protect themselves against the Indians who were camped in their valley. Upon receipt of this information, the people of Circleville called a town meeting. After much discussion, it was decided that they should arrest all the Paiutes that were camped nearby and bring them to Circleville for confinement. Every able-bodied man in the town set out to take custody of the Indian camp, and they surrounded the camp at night. James T. S. and Bishop William Jackson Allred went to the Indian camp and persuaded the Indians to come to a meeting at Circleville. They told the Indians that they had received a letter and they wanted to have it read to them. All of the Indians agreed willingly to go to Circleville with the men, except one young Indian warrior who refused to go and began to shoot at the posse. The posse returned fire, killing the young man. The rest of the Indians were then taken at gunpoint to Circleville and the letter was read to them. The Indians were told that they were to be retained as prisoners.

The Indians were taken into custody and placed in the meeting house that night under guard. The captured Indians, 26 in all, displayed much unrest. On the evening of the following day, some of the Indians were able to cut themselves loose from their bindings to escape. Guards shot and killed two Indians who were attempting an escape. The remaining imprisoned Indians were moved to an underground cellar. In a subsequent town meeting, the settlers decided to kill the remaining imprisoned Indians. The Indians were led out of the cellar, totaling 24 people, including men, women, and children. They were struck on the back of the head to stun them and then their throats were slit, leaving them to bleed to death. Two young boys and girl prisoner managed to escape before execution.

The following day, the three children were found in a nearby cave and taken by James Allred to Marysvale. Allred intended to sell or make a trade for the children. The little girl was killed by a violent bludgeoning. While the fate of one of the boys is unknown, the other Allred took to Spring City. There, Allred spoke with Peter Monson to offer the boy for sale. A deal was struck for a horse and bushel of wheat in exchange for the boy. The boy was locked in a toolshed for several days before receiving the name David Monson. According to John Munsen, Jr., his great-grandfather David Monson changed his name to Munsen. David lived in Wyoming until his death in 1925 at 67 years old. He is buried at Saratoga, Wyoming.

Scipio Raid and the Battle of Gravelly Ford

By June 1866 the threat against the Sanpete and Sevier settlements had grown with the telling. Black Hawk had threatened to bring enough men to destroy Manti and Warren Snow that year. 125 additional militia were sent south from Salt Lake to prevent such an attack. Black Hawk shifted his focus to Scipio upon being told of the show of strength in Sanpete Valley. Scipio illustrates the sometime personal nature of the attacks during the war. It was the home of the James Ivie family. Richard Ivie had been responsible for hostilities in the Fort Utah war when he murdered Bishop and sank his weighted body in the Provo River. James Ivie was blamed for starting the Walker War when he hit a Ute over the head with his gun and participating in the Tintic war which resulted in the death of Black Hawk's friend Squash Head and the wounding of Chief Tintic. A band of 100 Utes and allies began herding together 350 head of cattle from pastures near Scipio. They killed a 14-year-old herd boy and shot an elderly James Ivie full of arrows and stripped him of everything except his boots. Gathering up 75 horses the Utes and their allies moved the herd through Scipio Gap into Sevier Valley. Scipio's men charged out after the herd, but were forced back when the Black Hawk's rear guard moved to attack the town which had been left virtually undefended. The Utes withdrew moving toward Salina Canyon with the largest single capture of livestock in the conflict.

The Scipio settlers sent runners to Gunnison and Fillmore to get help. William Pace of the Nauvoo Legion gathered up 20 men hoping to catch Black Hawk before he could make his escape. They left Gunnison and marched through the night to reach Salina before the herd could be driven away. He could see the herd head for Gravelly ford on the Sevier River and rode there to stop the Utes from stealing the cattle and horses. Upon approaching the ford he found about 60 Utes guarding the ford. He sent for help from Richfield and tried to delay the fording of the herd with a prolonged gun fight. Realizing he could not sustain the attack, he ordered his men to pull back out of range. Several Utes tried to force them farther back from the ford by charging the nearly defenseless militia. Black Hawk himself and his chief lieutenant, Tamaritz, were two of these men. Black Hawk's horse was shot from under him and then he was hit in the stomach. Tamaritz, too, had been wounded. Minutes later the Gunnison militia, out of ammunition took to their heels. The Utes drove the herd across the river toward Salina Canyon just as the Richfield militia arrived on horseback to see the herd nearing the mouth of Salina Canyon and the Gunnison militia riding for home. The wounding of Black and Tamaritz eventually brought an end to the Black Hawk War and Black Hawk himself just four years later. In the interim several other sub chiefs took over including Black Hawk's brother, Mountain, Issac Potter and Richard James.

The attack on Scipio had two immediate consequences. Mormons who had since the beginning of the conflict been ordered to 'fort up' had resisted the order since the fighting was most often confined to Sanpete and Sevier Valeys. Scipio's failure to fort up was used as a bad example by LDS church leaders in their renewed call for forts to be built in larger towns and smaller outlying towns were to be abandoned until hostilities came to a halt. These temporary forts were often haphazardly built, but they would do against the lightly armed Utes and allies who were attacking white settlements.

The second involved the Ivie family again. James Ivie, the son of the elder Ivie murdered at Scipio, was crazy for revenge against the Utes. An old Pahavnt Ute medicine man by the name of Panikary made the mistake of visiting Scipio begging for food. He was known as a 'good Indian' with a peaceful disposition. Bishop Thomas Callister of Fillmore who happened to be in Scipio, advised Panikary to leave town because the Ivie's blood was up and there might be trouble. Panikary took the presents of food offered and headed toward Fillmore. Upon returning from the futile pursuit of Black Hawk, the younger James Ivie, hearing that a Ute had been in Scipio just hours before raced after Panikary and murdered him on the spot. The bishop of Scipio had ridden hard to stop Ivie but failed to prevent the killing. Callister was disgusted by the murder and rode directly to Chief Kanosh's camp to inform him of the incident. Up to that point the Pahavant Ute had not been openly involved in the fighting. Kanosh thanked Callister for being honest, but the war chief, Moshoquop and 27 warriors followed Callister to his home in Fillmore angrily demanding justice. Callister convinced the Utes that Brigham Young would be a fairer judge. The Utes agreed and rode away. Later Ivie was arrested and tried for murder by an all-Mormon judge and jury and was acquitted when it was suggested that Panikary was really a spy for Black Hawk. Bishop Callister was so upset by the outcome that he excommunicated Ivie from the church.

Battles of Thistle Valley and Diamond Fork

June 1866 brought the Uintah Utes into the conflict. Up until that time a few hot-headed young fighters joined Black Hawk but Chief Tabby-To-Kwanah (Tabby)and others had kept the Utes in the Uintah Valley reservation out of the war. The call for an additional 350 men from Salt Lake and Davis Counties to strengthen Mormon settlements angered Tabby and his fighters. But Black Hawk's brother, Mountain, Isaac Potter and Richard led separate war parties toward Utah Valley. They found a Nauvoo Legion detachment at what is now Indianola and attacked. The pinned the militia down for most of the day, but a second detachment under John L. Ivie arrived late and kept the first detachment from being overwhelmed. The soldiers were convinced that Chief Tabby had led the attack. When and additional 130 men under Warren Snow arrived, it was agreed to chase the Utes up Spanish Fork Canyon. Fearing another Salina Canyon disaster, the troops moved cautiously but on arriving at Soldier Summit Pass found that the Utes had split up and gone in different directions. He turned his men around and marched them back to Sanpete Valley.

Mountain had led his men to Spanish Fork to exact vengeance on William Berry who years before had beaten Black Hawk with an old bucket for a supposed theft. They killed Berry and drove off about forty cattle and horses and fled into the Wasatch Mountains through Maple Canyon. The militia, who were already on alert, gave chase. They intercepted the Utes at Diamond Fork River but were outnumbered and pinned down by desultory rifle shots and arrows. A second force of eight men rushed the Utes and three were shot dead. The others put the Utes in a crossfire. The Utes quietly withdrew leaving the livestock and camp to be plundered by the militia. Among the gear they found US issued items, which showed the Utes had been accepting food and supplies at the Uintah Reservation. Leaders of the militia swore affidavits that white men had been seen directing the Utes. It was feared that the US Indian officials were aiding and abetting the Utes in their war against the Mormons.

These incidents were a turning point in the war. Mormons had begun to be vigilant as Brigham Young had repeatedly encouraged them to do. Fort building and evacuations of small settlements, combining livestock herds under guard, and the hundreds of additional soldiers patrolling commonly used canyon trails stymied the ability of Utes to drive off the numbers of cattle and horses of the first two years in the war. Tabby used his influence after the defeat of the reservation Utes to keep most of his people out of the conflict. It would not be until 1872 in the final days of the war that reservation Utes caused any more trouble. The 'defeat' of the reservation Utes encouraged Mormons to continue to prevent attacks whenever possible.

Black Hawk's Last Raid

In the spring of 1867 hundreds of Nauvoo Legion militia from northern Utah flooded into central Utah determined to maintain the strict vigilance on settlements and their livestock, and patrol routes known to be used by Utes and their allies. There were several isolated attacks, one of which was planned to capture and kill Warren Snow, which was narrowly averted. Dozens of ranches and settlements were closed and more and more settlers moved to towns with forts for protection. With such a military presence in central Utah, Black Hawk moved his forces south and planned a raid on Parowan in Iron County, which until that time had not suffered anything but anxiety. By July 21, 1867 a large herd of 700 cattle and horses that had been gathered and placed under guard seemed to be the main target, but other raiders began to round up scattered livestock near Paragonah when they were seen by guards and the alarm was raised. The Utes were chased into a canyon where the Utes were eventually forced to leave their horses behind in order to escape in the steep terrain. Black Hawk retreated recognizing that it would be impossible to get any stolen livestock over the high plateaus above Cedar City and Parowan.

Black Hawk had never fully recovered from his wound at Gravelly Ford the previous year. He also had tuberculosis and his health was failing. Two weeks later in August Black Hawk and a small band of followers rode into the Uintah Reservation and announced to the agent there that he was ready to talk peace with the whites.

Death of Isaac Potter

Isaac Potter was a white man, a former Mormon with several wives in Utah County who had turned outlaw. He became one of the principal brokers in the sale of Black Hawk's stolen cattle. Reports of white men leading Ute raids were common and Ike Potter was the most notorious of them. In late June 1867 Ike Potter and a band of Utes and allies sent a demand for beef and other supplies to William W. Cluff, a Mormon Bishop at Coalville in Washington County. The demand was rejected and Potter responded that Black Hawk would come down and wipe out the Mormons. A raid on a sawmill brought out the militia, which accidentally learned where Potter and his men were camped. They surrounded the camp and arrested Potter, two other whites, 16 Utes and Navajos on the charge of stealing one cow. They were marched back to Coalville to stand trial. The Mormons were afraid that Potter would be freed by a 'gentile' judge and decided to take matters into their own hands. The three white men tried to escape on the night of August 1, while 'attacking' his guards Potter was shot and his throat cut, a second made it as far as the Virgin River where he was shot multiple times, the third escaped wounded.

Negotiations

With Black and his family at the Uintah Reservation willing to negotiate, the US government finally stepped into its own. Superintendent Franklin Head rode to the Uintah Agency to work out a peace agreement that would bring hostilities to an end. He found all of the chief s of the Northern Utes already gathered ready to talk. By mid-September the government had everything it wanted from Black Hawk. Not only would he stop raiding, he promised to use his influence to persuade Tamawitz and others to come to the Uintah Agency and stop harassing whites. Black Hawk explained that it wasn't his band that caused all the trouble blaming Elk Mountain Utes for the trouble.

The spring of 1868 began as a hopeful one for displaced Mormon settlers. They clamored to return to their homes, farms, ranches, and towns. The very first wagon train to take back the Sevier Valley settlements was attacked by Tamaritz and a small force. The resettlement was postponed for at least a year. There were a few attacks on individuals and isolated thefts, but the Mormon vigilance policy prevented Ute success. Black Hawk sent messages to leaders either once under him or allied with him to come in and negotiate with the government. His treatment was a positive example and one or two raiders made their way to the Uintah Reservation. Tamaritz and his band surrendered in August.

Negotiations between local Utes and settlement leaders took place all through the summer. Tabby met with leaders in Heber City, Orson Hyde met with Sowiette, Toquana in Nephi, Indian agent Dimick Huntington met with Ute in the Strawberry Valley, and Hamilton Kearnes met with Ute at Salina to smoke a peace pipe and give presents. Elk Mountain chiefs met with Superintendent Head and the fighting seemed to be coming to a swift conclusion. In the minds of Mormon settlers and territorial officials the war was over. Subsequent isolated incidents between settlers and Native peoples in central and southern Utah, though not directly connected to the Black Hawk War, are included by modern historians extending dates of the war from 1868 until the forced relocation of all Utes to the Uintah Agency in eastern Utah in 1872.

Ghost Dance

As chief after chief gave up hostilities tensions slackened in 1869. There were reports of murdered Utes who happened to be in the wrong place when accosted by whites bent on vengeance. For example Ute girl raised in a Mormon family in Fairview was found with her throat cut and the crime never truly investigated. There were sporadic raids where a few horses were taken or a cow slaughtered by unknown parties. The Uintah Reservation was not a peaceful place, Ute from many bands were forced to live in close proximity which caused problems and the younger fighters wanted to be out raiding, but held in check by their leaders.

1870 brought an early version of the Ghost Dance to Utah. The main beliefs came from Nevada Paiutes who taught that there was a way to bring back the ancestors, those who had died long ago and the recently deceased. Those who wished to participate needed to go the a great meeting and those who refused would get sick and die. Thousands of Northern Utes, Shoshones, and Bannocks met near Soda Springs, Idaho for the vision to occur. The gathering alarmed both territorial officials and federal appointees who feared that the meeting might be the start of a great confederation to drive out whites from the valleys. Ute chiefs assured the superintendent that the meeting was religious in nature and not intended as the threat to anyone. The event occurred without incident and everyone returned to their homes.

1871 brought a new governor to Utah Territory who had pledged that after him, governors, not Brigham Young, would govern in Utah. One of his first acts was to disband the Nauvoo Legion, Utah's territorial militia. Musters and drills were forbidden and officers decommissioned while hundreds of additional troops were moved to Fort Douglas overlooking Salt Lake City. Brigham Young and Daniel Wells were arrested for cohabitation. The Nauvoo Legion refused at first to comply and things came to a head at the 4th of July Parade in 1871 where the Legion had always marched. The post commander at Fort Douglas was prepared to use force to prevent the militia from marching. The Legion blinked first and the confrontation ended. Emboldened, Governor Schaffer went on to prohibit any group of armed men from going out to recover stock without written permission. The letter that were forwarded to him went unanswered and the only recourse was to ask for troops from Fort Douglas to intervene. This left settlers without any real protection from the occasional thefts and threats which arose in outlying areas. This set the stage for the final act of Utah's Black Hawk War.

The Northern Utes had agreed to host the Ghost Dance meeting and the site chosen by a vision was near Fountain Green in Sanpete Valley. By May of that year and estimated 2,000 Utes had gathered there. Another 2,000 Shoshones under Chief Washakie were already in transit, rumor had it that thousands of Sioux, Cheyenne and other eastern tribes were expected as well. All were awaiting the appearance of the Voice of the West, a Paiute prophet who would 'foretell the future of Indians in America'. Such an amazing gathering frightened Sanpete residents who feared that the Utes would finally get their ultimate revenge for the killings in the Black Hawk War. Federal officials believed that somehow Brigham Young had orchestrated the meeting to get control of Native People. Voice of the West did not appear, so Indians settled down to wait. Residents of the towns were soon besieged with requests for food and presents. Leaders soon wrote to the governor complaining that men were compelled to go about town armed day and night to protect themselves and their property. The federal officials were afraid that troops might spark trouble and did nothing. White traders soon found a ready market for whiskey and ammunition. By June the Shiberetch Utes declared it was time to make war on the Mormons and invited anyone to join them in Grass Valley in the mountains east of Sanpete Valley. They killed a herdboy as they made their way through and out of the valley. Stock raids immediately commenced in Sanpete and Sevier Valleys. Realizing that Mormon authorities were powerless to help, residents appealed directly for help from the commandant at Fort Douglas, an unprecedented step in Indian affairs. Utes were murdered indiscriminately in revenge killings and the reports falsified to hide the extent of the settlers' countermeasures.

Alarmed at the sudden outbreak of hostilities, Daniel Well appealed to General Morrow for assistance in quelling the new uprising fearing that the limited conflict could quickly spin out of control. Morrow agreed and promptly called up 500 former Nauvoo Legion militiamen to march south to disperse the Ghost Dance. Fortunately, with more cooperation and restraint on all sides a massacre was avoided, and the various groups of Indians gathered for the Ghost Dance ceremony were dispersed. The Utes were ordered to return to the Uintah Reservation. Two more Mormons were murdered that year and unknown number of Utes and other Native Americans were murdered in revenge killings. The Northern Ute resistance was ended when federal troops were deployed to keep Utes on the Uintah Reservation. The Black War in Utah had ended.

Outcomes

Utah's Black Hawk War had far-reaching and unforeseen outcomes for Mormons and Utes alike. After 1872 Mormons in Utah were able to expand settlements as immigrants swelled valley populations without the threat of Ute resistance. The chasing of Ute raiders through unexplored regions of Utah actually helped explore areas for new settlements as outliers of the larger towns. Ranchers were free to take up land far from population centers without fear of being attacked. Mormons came to accept the army as a force that could do its job without threatening local autonomy. Communities became more independent as they realized that local decisions were often better tailored to suit local conditions than requesting advice from Salt Lake. Mormons were less able to control the functions of government as federal officials began their long crusade to end polygamy and Mormon control of government and the economy.

Black Hawk's War was a disaster for the Northern Utes. They were forced permanently onto the Uintah Reservation to live dependent on corrupt government agents. No promises made in any treaty were fulfilled completely. Terms of treaties which restricted the Utes were rigidly enforced, but promises in the treaty which territorial officials and Mormon leaders put their names to were largely ignored. Intra-tribal divisions arose which persisted to modern times. The Ute were forced to give up their traditional way of life and left to fend for themselves in one of the least habitable parts of Utah. Disease, living conditions, hopelessness, alcoholism, and poverty reduced Ute populations drastically. While it is difficult to estimate moving populations, Dimick Huntington, an interpreter for the territorial government, estimated that there were perhaps 23,000 Native Americans in Utah in 1865. In 1872 he estimated the number at 10,000. While these numbers seem exaggerated to modern historians, it indicates that the period took a terrible toll on the Utes. Not everyone in those estimates died, many simply moved out of the territory, but the number of deaths by disease, starvation, and the war was catastrophic for Northern Utes. Ute population continued the steep decline, so that as of this writing (2008) there are 3,120 Northern Utes enrolled, up from 2500 in 1980.

See Also

Notes

- ↑ The Black Hawk War in Utah, by Phillip B. Gottfredson Archived April 6, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ 41st Congress, House of Representatives. Mis. Do. 1st Session. No. 10. Memorial of the Legislative Assembly of Utah Territory, For an appropriation to pay for Indian depredations and expenses incurred in suppressing Indian hostilities.

- ↑ "Utah History of the Black Hawk War". Official Web Site for the State of Utah. Retrieved March 20, 2008. Originally from: John A. Peterson (1994). "Black Hawk War". Utah History Encyclopedia. University of Utah Press. Retrieved 2015-08-31.

- ↑ Martin, James R. "How can you buy or sell the earth?". Management and Accounting Web. Retrieved December 28, 2012.

- ↑ Sanpete County Commissioners (1982). "Indian Encounters". In Antrei, Albert C.T. The Other Forty-Niners: A topical history of Sanpete County Utah 1849–1983. Ruth D. Scow. Salt Lake City, Utah: Western Epics. pp. 127–148. ISBN 0-914740-26-1.

- ↑ Lowry, Walker (1974). Wallace Lowry (1st ed.). Lunenburg, Vermont: Stinehour Press. p. 51.

- 1 2 Gottfredson, Peter (30 September 2002) [1919]. Indian Depredations in Utah. Fenestra Books. pp. 323–335. ISBN 1587361272.

- ↑ Mciff, Rose (1970). "Weep Not for Me Mother" (PDF). Saga of the Sanpitch. 2. Snow College & University of Utah: Sanpete Historical Writing Committee. p. 18.

- ↑ STATEMENT, M. S. MARTENAS, INTERPRETER Great Salt Lake City, July 6, 1853 Brigham Young Papers, MS 1234, Box 58, Folder 14 LDS Archives - Will Bagley Transcription.

- ↑ Olsen, John K. (1979). "What did Walker Want?" (PDF). Saga of the Sanpitch. 11. Snow College & University of Utah: Sanpete Historical Writing Committee. p. 17.

- ↑ Sonne, Conway Ballantyne (1962). World of Walkara. San Antonio, Texas: Naylor Co. pp. 161–205.

- ↑ Phillip B. Gottfredson. "Facts Concerning the Utah Black Hawk War". lack Hawk War Productions. Retrieved 2013-08-17.

- ↑ - John Alton Peterson Utah's Black Hawk War - Rod Miller's Massacre at Bear River

References

- Culmsee, Carlton Fordis (1973). Utah's Black Hawk War: lore and reminiscences of participants. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press. ISBN 0-87421-060-7. LCCN 73082365.

- Gottfredson, Peter, ed. (1919). History of Indian Depredations in Utah. Salt Lake City, Utah: Fenestra Books. ISBN 1-58736-127-2. (Scanned copy from Harvard College Library available from Google Books)

- Peterson, John Alton (1998). Utah's Blackhawk War. University of Utah Press. ISBN 0-87480-583-X.

- Sanpete County Commissioners (1982). Antrei, Albert C.T.; Scow, Ruth D., eds. The Other Forty-Niners: A topical history of Sanpete County Utah 1849–1983. Salt Lake City, Utah: Western Epics. ISBN 0-914740-26-1.

- Utah Indian War Records; MSS SC 2234; 20th Century Western and Mormon Manuscripts; L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.