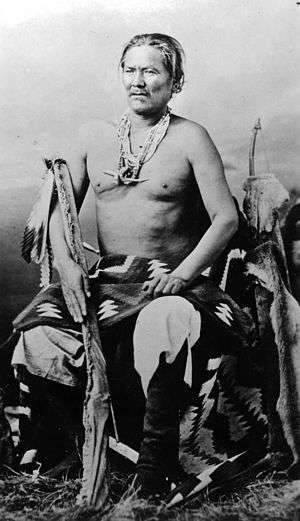

Manuelito

| Manuelito | |

|---|---|

| Hastiin Chʼil Haajiní | |

| |

| Navajo leader | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

c. 1818 Bears Ears, Southeastern Utah |

| Died |

1893 Manuelito Springs, New Mexico |

| Cause of death | Measles; pneumonia |

| Spouse(s) | Asdzáá Tl'ógí, ("Weaver Woman") |

| Known for | Resisting the Long Walk of the Navajo and a Navajo War leader |

| Military service | |

| Nickname(s) | Ashkii Diyinii |

| Battles/wars | Americans and New Mexico Raiders/Mexicans, Apache Wars |

Chief Manuelito (1818–1893) was one of the principal war chiefs of the Diné people before, during and after the Long Walk Period. His name means Little Manuel in Spanish. He was born to the Bít'aa'níí or ″Folded Arms People Clan″,[1] near the Bears Ears in southeastern Utah about 1818. As any Navajo, he was known by different names depending upon context. He was Ashkii Diyinii (Holy Boy), Dahaana Baadaané (Son-in-Law of Late Texan), Hastiin Ch'ilhaajinii ("Man of the Black Plants Place")[2] and as Nabááh Jiłtʼaa (War Chief, "Warrior Grabbed Enemy") to other Diné, and non-Navajo nicknamed him "Bullet Hole".

Manuelito was a prominent Navajo leader who rallied his nation against the oppression of the United States military. For several years he led a group of warriors in resisting federal efforts to forcibly remove the Navajo people to Bosque Redondo, New Mexico via the Long Walk in 1864. After being relocated to Bosque Redondo, Manuelito was among the leaders who signed the 1868 treaty, ending a period of imprisonment in United States government internment camps and establishing a reservation for the Navajo. Manuelito was also an advocate for education for Navajo children.

Early life

Manuelito was born into the Bit'ahni Clan (Within his cover clan) near Bears Ears, Utah where he was born and raised.

He married Juanita a daughter of Narbona (1766 – August 30, 1849) after joining Narbonas Band, and went to live at their camp near the Chuska Mountains.

Narbona's reputation as a wealthy and powerful headman impressed Manuelito. He especially admired Narbona's fearless attitude, although Narbona tried to teach him the value of peace as well as war.

Manuelito spent his days shooting arrows and competing with other young men in countless foot races and wrestling matches, always winning. He dressed in well-fitting buckskins and a finely woven blanket. He couldn't wait for his first battle.

When word came in the winter of 1835 that 1000 Mexicans (from New Mexico) were coming to attack the Navajos, Manuelito fought his first in what would be many violent battles. There he earned the name Hashkeh Naabaah (″Angry Warrior″).

In the years that followed, Manuelito led one raiding party after another, joining forces with other leaders such as Ganado Mucho and Barboncito to attack not only the hated Mexicans, but also the Hopis in Arizona, the Puebloan peoples of New Mexico, the Utes, the Comanches, and the Apaches. Food supplies, livestock, and women and children were all fair game, and eventually Manuelito married one of his many Mexican slaves, Juanita (1845-1910).[3]

Juanita's Navajo name was Asdzáá Tl'ógí, ("Weaver Woman"); a dress and saddle blanket woven by Juanita survive to this day. Her biographer and great-great-great granddaughter Jennifer Nez Denetdale describes taking a trip to Los Angeles to view the dress.[4]

Pre-Long Walk

- 1835 Battle of Washington Pass, Manuelito took part in Narbona's victorious party that defeated a large raiding force led by Captain Blas de Hinojos at what today is called Narbona Pass. He was seventeen when he earned the name Hashkeh Naabaah (″Angry Warrior″).

- 1846 One of the signatories of the 22 November 1846 Lava Springs Treaty..

- 1849 Present when Col. John M. Washington met with his father-in-law Chief Narbona in the Chuska Mountains and Narbona was killed.

- 1853 He and Chief Aguila Negra visited Lt Ransom detachment at the mouth of Chaco River, where Chief Archuleta joined them and created a disturbance.

- July, Chief Sarcillos Largos retires and Manuelito was elected to speak for the Navajos. This was at the time when a proposed treaty to separate Navajo and Mexican/American grazing lands was under consideration.

- 1855, July Zarcillos Largos and Manuelito signed The Meriwether Treaty on July 18, 1855 at Laguna Negra with Americans. Manuelito was recognized as 'official chief' and receives a peace medal.

- 1856 Major Kendrick at Ft. Defiance spoke to Manuelito about stock stolen by some Navajo (one of many times Manuelito filled this role).

- 1857 He objects to army pastures around Ft. Defiance, but relents.

- 1858 Manuelito told Major Brooks, commander Ft. Defiance that Navajos need the pastures (Ewell's Hay Camp) around the Fort for their livestock. Manuelito's band moved their stock closer and a skirmish happened and Manuelito lost over 100 cattle and other livestock.

- 1858 Major Brooks' servant molested a Navajo woman and, as custom dictated, Navajos killed the offender. After a brief campaign both sides signed a treaty.

- 1860

- July, 50 Mexican/Americans from Cubero, NM raid summer camps. Manuelito and Sarcillos Largos set a successful ambush at Whiskey Lake in the Chuska Mountains. 40 of the raiders died.

- December 400 volunteer citizens mount a campaign against the Navajos

- 1861 Major Canby, Commander at Ft Wingate submitted a list with Navajo chiefs and Manuelito was listed as 5th.

- 1864, Start of Long Walk period. His band are still in Dinetah, perhaps southwest of the Little Colorado River.

- 1865 Jesus Arviso, Navajo interpreter, was sent by Major Eaton of Ft. Wingate to tell Manuelito to come in.

- Later Herrero Grande and Fecundo were sent from Ft. Sumner to Zuni to tell him to come in.

- Utes attacked Manuelito's camp .

- 1866

- July. Zunis and Utes attack Manuelito's band south of Sierra Escudilla (near Springerville AZ).

- September. Manuelito and his band come to Ft. Wingate and go to Bosque Redondo. Ganado Mucho and his band went to the Bosque from Escudilla by another route.

- 1867, September Manuelito leaves to raid Utes, after Comanches and then Utes raid Navajos at Bosque Redondo. He and his band returned.

- 1868 He is one of the signers of the Treaty of Bosque Redondo which ended the Long Walk.

Post Long Walk

Manuelito, as he was known to the white settlers and government forces, was Ashkii Diyinii, Holy Boy, to his own people, later to earn the name Haastin Chʼil Haajiní, or Sir Black Reeds, named for 'the place among the black reeds'.

Upon his return, he again lived east of Tohatchi. He became principal chief after Barboncito of the eastern Navajos.

- 1872 Manuelito was appointed as head of the new Navajo police force.

- 1876 Talked to President Grant regarding land problems involving encroachment and potential leases of treaty given lands.

- 1879 Crops failed and Navajos raided citizens and Zunis. Manuelito and Ganado Mucho arrested 40 men as thieves or witches.

- 1880 Meets President Hayes in Santa Fe. Also suggests that he be made "Chief of Scouts" to control whiskey traffic in eastern part of reservation.

- 1882 Navajos and white settlers argue over land that Manuelito says is theirs. He sends his two sons to Carlisle Indian Industrial School. He requests pipes for water and receives a permit to hunt off the reservation with 20 men.

- 1883 Manuelito's two sons fall sick at Carlisle Indian Industrial School. One son dies at the school, the other returns home, dying soon after his return. Agent reports 4,000 Navajo follow Manuelito in eastern reservation area.

- 1886 Manuelito and Mariano were sent out to recruit Navajo Scouts for the Army.

- 1891 Army pays call upon him and Tom Torlino, and he gives advice about improving flow of springs.

- 1892 Is called to Ft. Wingate to discuss certain renegade Navajos who were raiding stock belonging to non-Navajos.

- 1893 Manuelito dies from measles complicated by pneumonia

See also

References

- ↑ "LAPAHIE.com 6.5 \ Manuelito (1818-1893), Navajo Chief". www.lapahie.com. Retrieved 2015-10-12.

- ↑ "LAPAHIE.com 6.5 \ Manuelito (1818-1893), Navajo Chief". www.lapahie.com. Retrieved 2015-10-12.

- ↑ Denetdale, Jennifer Nez (2007). Reclaiming Diné history: the legacies of Navajo Chief Manuelito and Juanita. Tucson: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 9780816524204.

- ↑ Cook, Roy. "Reclaiming the Pride of the Dine' Culture". Navajo Times. Retrieved 2014-06-04.

- Correll, J. Lee. Manuelito, Navajo Naat'aani: About 1820 to 1894, unpublished draft for The Navajo Times edition 9 Sept 1965. Copy has 101 footnotes with citations.

- Compiled (1973). Roessel, Ruth, ed. Navajo Stories of the Long Walk Period. Tsaile, Arizona: Navajo Community College Press. ISBN 0-912586-16-8.

- Grant, Bruce. Concise Encyclopedia of the American Indian, Wing Books: New York, 2000.

- Thompson, Gerald (1976). The Army and the Navajo: The Bosque Redondo Reservation Experiment 1863-1868. Tucson, Arizona: The University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-0495-4.

External links

- Bosque Redondo/Fort Sumner

- Oral history of Manuelito compiled by Harrison Lapahie Jr.

- Famous Indian Chiefs I Have Known by General O. O. Howard circa 1908