Hyperboloid

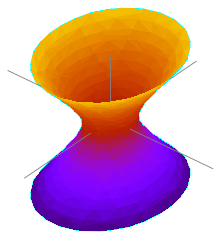

Hyperboloid of one sheet |

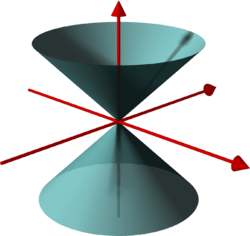

Common conical surface |

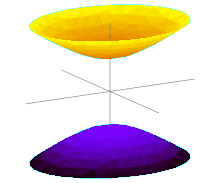

Hyperboloid of two sheets |

In mathematics, a hyperboloid is a quadric in three dimensions described by the equation

- (hyperboloid of one sheet or hyperbolic hyperboloid),

or

- (hyperboloid of two sheets or elliptic hyperboloid).

Both of these surfaces asymptotically approach the same conical surface as x or y becomes large:

If and only if a = b, it is a hyperboloid of revolution, and is also called a circular hyperboloid.

Cartesian coordinates

Cartesian coordinates for the hyperboloids can be defined, similar to spherical coordinates, keeping the azimuth angle θ ∈ [0, 2π), but changing inclination v into hyperbolic trigonometric functions:

One-surface hyperboloid: v ∈ (−∞, ∞)

Two-surface hyperboloid: v ∈ [0, ∞)

Generalised equations

More generally, an arbitrarily oriented hyperboloid, centered at v, is defined by the equation

where A is a matrix and x, v are vectors.

The eigenvectors of A define the principal directions of the hyperboloid and the eigenvalues of A are the reciprocals of the squares of the semi-axes: , and . The one-sheet hyperboloid has two positive eigenvalues and one negative eigenvalue. The two-sheet hyperboloid has one positive eigenvalue and two negative eigenvalues.

Properties

A hyperboloid of revolution of one sheet can be obtained by revolving a hyperbola around its semi-minor axis. Alternatively, a hyperboloid of two sheets of axis AB is obtained as the set of points P such that AP−BP is a constant, AP being the distance between A and P. Points A and B are then called the foci of the hyperboloid. A hyperboloid of revolution of two sheets can be obtained by revolving a hyperbola around its semi-major axis.

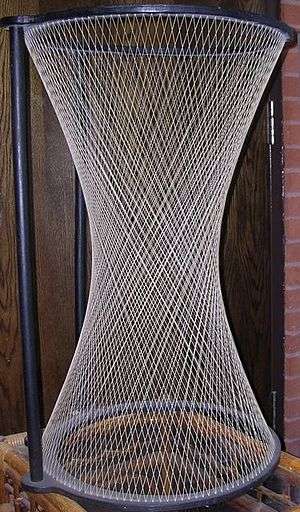

A hyperboloid of one sheet is a doubly ruled surface; if it is a hyperboloid of revolution, it can also be obtained by revolving a line about a skew line.

Whereas the Gaussian curvature of a hyperboloid of one sheet is negative, that of a two-sheet hyperboloid is positive. In spite of its positive curvature, the hyperboloid of two sheets with another suitably chosen metric can also be used as a model for hyperbolic geometry.

In more than three dimensions

Imaginary hyperboloids are frequently found in mathematics of higher dimensions. For example, in a pseudo-Euclidean space one has the use of a quadratic form:

When c is any constant, then the part of the space given by

is called a hyperboloid. The degenerate case corresponds to c = 0.

As an example, consider the following passage:[1]

- ... the velocity vectors always lie on a surface which Minkowski calls a four-dimensional hyperboloid since, expressed in terms of purely real coordinates (y1, ..., y4), its equation is y2

1 + y2

2 + y2

3 − y2

4 = −1, analogous to the hyperboloid y2

1 + y2

2 − y2

3 = −1 of three-dimensional space.

However, the term quasi-sphere is also used in this context since the sphere and hyperboloid have some commonality (See § Relation to the sphere below).

Hyperboloid structures

One-sheeted hyperboloids are used in construction, with the structures called hyperboloid structures. A hyperboloid is a doubly ruled surface; thus, it can be built with straight steel beams, producing a strong structure at a lower cost than other methods. Examples include cooling towers, especially of power stations, and many other structures.

Relation to the sphere

In 1853 William Rowan Hamilton published his Lectures on Quaternions which included presentation of biquaternions. The following passage from page 673 shows how Hamilton uses biquaternion algebra and vectors from quaternions to produce hyperboloids from the equation of a sphere:

- ... the equation of the unit sphere ρ2 + 1 = 0, and change the vector ρ to a bivector form, such as σ + τ √−1. The equation of the sphere then breaks up into the system of the two following,

- σ2 − τ2 + 1 = 0, S.στ = 0;

- and suggests our considering σ and τ as two real and rectangular vectors, such that

- Tτ = (Tσ2 − 1 )1/2.

- Hence it is easy to infer that if we assume σ λ, where λ is a vector in a given position, the new real vector σ + τ will terminate on the surface of a double-sheeted and equilateral hyperboloid; and that if, on the other hand, we assume τ λ, then the locus of the extremity of the real vector σ + τ will be an equilateral but single-sheeted hyperboloid. The study of these two hyperboloids is, therefore, in this way connected very simply, through biquaternions, with the study of the sphere; ...

- ... the equation of the unit sphere ρ2 + 1 = 0, and change the vector ρ to a bivector form, such as σ + τ √−1. The equation of the sphere then breaks up into the system of the two following,

In this passage S is the operator giving the scalar part of a quaternion, and T is the "tensor", now called norm, of a quaternion.

A modern view of the unification of the sphere and hyperboloid uses the idea of a conic section as a slice of a quadratic form. Instead of a conical surface, one requires conical hypersurfaces in four-dimensional space with points p = (w, x, y, z) ∈ R4 determined by quadratic forms. First consider the conical hypersurface

- and

- which is a hyperplane.

Then is the sphere with radius r. On the other hand, the conical hypersurface

- provides that is a hyperboloid.

In the theory of quadratic forms, a unit quasi-sphere is the subset of a quadratic space X consisting of the x ∈ X such that the quadratic norm of x is one.[2]

See also

- Ellipsoid

- Hyperbola

- Hyperboloid structure

- Paraboloid / Hyperbolic paraboloid

- Ruled surface

- Rotation of axes

- de Sitter space

- Translation of axes

- Vladimir Shukhov

References

- ↑ Thomas Hawkins (2000) Emergence of the Theory of Lie Groups: an essay in the history of mathematics, 1869—1926, §9.3 "The Mathematization of Physics at Göttingen", see page 340, Springer ISBN 0-387-98963-3

- ↑ Ian R. Porteous (1995) Clifford Algebras and the Classical Groups, pages 22, 24 & 106, Cambridge University Press ISBN 0-521-55177-3

- Wilhelm Blaschke (1948) Analytische Geometrie, Kapital V: "Quadriken", Wolfenbutteler Verlagsanstalt.

- David A. Brannan, M. F. Esplen, & Jeremy J Gray (1999) Geometry, pp. 39–41 Cambridge University Press.

- H. S. M. Coxeter (1961) Introduction to Geometry, p. 130, John Wiley & Sons.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hyperboloid. |