Line 2 Bloor–Danforth

Line 2 Bloor–Danforth[3] is a subway line in the Toronto subway system, operated by the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC). It has 31 stations[3] and is 26.2 kilometres (16.3 mi) in length. It opened on February 25, 1966, and extensions at both ends were completed in 1968 and again in 1980.

The most travelled part of the line is located in Old Toronto's midtown area known as Yorkville.[4] In this area, the subway also connects to Line 1 Yonge–University at Spadina, St. George and Yonge stations. Towards the east, the line runs parallel to Danforth Avenue serving areas such as Greektown and the East Danforth, it then continues further to the east through a very short stretch in East York to its eastern terminus in Scarborough, where it connects to Line 3 Scarborough. To the west, the line continues along Bloor Street serving many communities such as The Annex, Bloor West Village, an extremely short stretch in York, and the area surrounding the line's western terminus located in Etobicoke.

The line runs primarily a few metres north of Bloor Street from its western terminus at Kipling Avenue to the Prince Edward Viaduct east of Castle Frank Road, after which the street continues as Danforth Avenue. Just east of Main Street, the line begins to deviate north-east from Danforth Avenue and runs grade-separated until its eastern terminus, slightly east of Kennedy Road on Eglinton Avenue. The subway line is closed nightly for maintenance, when Blue Night Network bus routes serve the route.[5]

Name

When the Bloor-Danforth line, the second subway line in the city opened in 1966, it necessitated the renaming of the first subway line to the Yonge line. Unofficially, subway lines were already numbered, but in October 2013, the TTC announced plans to give the lines an official number to help riders and visitors to navigate the system. The new signage was commenced in March 2014 with Bloor–Yonge and St. George stations being the first to do so.[6][7] The subway used to be internally known as route 601[8] and since the mid-2010s, it is called 2 Bloor–Danforth Subway.[9]

History

Pre-subway era

The earliest mention of rapid transit along the Bloor–Danforth line's route was made in a 1910 report that was prepared by an American firm of transit consultants. This study had been commissioned by a special commission which included City Controller Horatio Clarence Hocken and Mayor of Toronto Joseph Oliver. In their final report, the consultants suggested that the Prince Edward Viaduct, which spans the Don River Valley, should include a lower deck for a future subway.[10] The lower deck was built, but the first plan for a line to use it was not made until June 15, 1933, when the TTC published a report which suggested construction of a subway and an expressway broadly following Bloor Street and Danforth Avenue. The estimated cost of the project was $120 million, but the plan was not implemented. Plans for a somewhat longer route, running east to west from Victoria Park Avenue to the Humber River, were proposed by the Toronto Planning Board in December 1943, although the report did not include costings.[11] During the fall of 1911, the City of Toronto put out a tender for the construction of concrete tubes to carry a subway. However, when the cost of the subway was put to a referendum, the construction of the subway tunnels was rejected.[12]

Before the subway was built, the TTC operated streetcars along the route between Jane Street and Luttrell Avenue. Paired PCC streetcars or multiple units (MUs) operated from 1950 to the opening of the subway line in 1966.[4] The TTC favoured this route because the Prince Edward Viaduct made it easier to build a subway across the Don Valley, and the streetcar that ran along the route was filled with passengers travelling from East York and Scarborough. To provide relief to this streetcar line and to make it easier to expand into the suburbs, the line was built under Bloor street and Danforth Avenue.[13]

Subway construction

During the period after World War II, rapid development created a need for more public transit. A referendum on whether a subway should be constructed along Yonge Street was held on January 1, 1946, and this proposal received majority support.[14] The opening of the Yonge subway in 1954 resulted in another plan by the TTC for a Bloor–Danforth line, this time without an expressway, costing $146 million ($1.313 billion in 2016 dollars). The line was approved, but was not built.[11]

In the 1950s, there was intense debate over where the second Toronto subway line would run as it would affect how bus routes in Toronto's suburbs would operate.[15] There were two main plans. While both shared the same route at the outer ends, the TTC favoured a route that continued eastwards from Christie station to Pape station. This plan was championed by the TTC chairman, Allan A. Lamport, and also included an extension of the Yonge line from Union Station northwards to meet the new line at St. George station. The other plan, which was proposed by the city's planning department and endorsed by its chairman, Fred Gardiner, had a large "U"-shaped diversion in the centre. From Christie, it ran south to Queen Street West, and after following Queen Street eastwards to Pape Avenue, turned north to rejoin the east-west route at Pape station.[16]

In 1956, Toronto's midtown area was starting to experience growth.[4] There was a public debate about the two schemes between the two chairmen and the municipalities that made up Metropolitan Toronto. The extension of the Yonge line along University Avenue, and the east-west Bloor–Danforth line extension were authorized on September 5, 1958[11] by the Ontario Municipal Board which sought a compromise between the involved communities.[17]

The University line opened in 1963, and the Bloor–Danforth line opened from Keele station in the west to Woodbine station in the east on February 26, 1966. Nine men died during its construction. Most of the line is underground and built using the cut-and-cover method, with some sections built using a tunnel boring machine. Other parts of the line are above ground in grade separated rail corridors. The line was 12.9 kilometres (8.0 mi) long,[11] and ran alongside Bloor Street and Danforth Avenue.[18]

Once the line started full operation, construction of extensions to the Bloor–Danforth line began. The extensions to Islington Station in the west and Warden Station in the east opened simultaneously on May 11, 1968.[19] On November 21, 1980, the line was extended to the current terminal stations of Kipling station in the west and Kennedy station in the east.[20]

Subway operations

Upon opening, the Bloor–Danforth line was well received: a survey taken four months later showed that the subway was used by 10,000 riders per hour. As a result, many bus and streetcar routes were either discontinued or shortened.[21] Various bus and streetcar routes, which connected to the subway stations allowed the line to continue to grow and become more sustainable.[22] The line carries an average of 519,180 passengers on weekdays during the 2011–2012 operating year.[2] For the first six months of operation, alternate trains forming the Bloor–Danforth subway service were routed along the new University Avenue line to Union Station. However, the manoeuvre made operation of both lines more difficult, and the practice was abandoned after the initial trial period.[11]

In 1971, Metro Council insisted that the zone fare system be removed to allow residents of the suburbs to travel anywhere with a single fare.[23] Prior to this, stations west of Old Mill and east of Victoria Park were geographically part of the zone 2 fare zone, but the subway used a flat fare system, so they were treated as being part of zone 1. This created problems when transferring from the subway to the buses, which were in different zones at the same location. The solution was a change in political thinking, where the subway was seen as a subsidized public service, instead of a utility which needed to balance its books.[24]

On October 15, 1976, an arsonist lit a fire on a subway train at Christie station. The fire destroyed four subway cars and some wall tiles, and resulted in a section of the subway being closed for a few days.[25] On September 19, 2007, the station modernization program was started.[26] This program would result in making the subway system more accessible,[27] add new bus and streetcar platforms,[28] and improve the connections to regional buses and GO trains.[29]

Stations

The western terminus of the Bloor–Danforth line is located near Kipling Avenue and Bloor Street West. After going east for 12 kilometres (7.5 mi), it meets the University segment of Line 1 at both Spadina and St. George stations. It also meets the Yonge Street line at Yonge station. The route's eastern terminus is located at Kennedy station, which is also the southern terminus of Line 3 Scarborough.[30] The line does not run under Bloor Street or Danforth Avenue, except at the Prince Edward Viaduct; otherwise it is offset to the north. In some areas, it runs under parks and parking lots behind the businesses on the north side of the street, while other sections run under side streets.[31]

Most stations on the Bloor–Danforth line have side platforms; however, there are still a few stations which use a centre platform instead.[32] At the surface, some stations are designed to be a part of the shopping area which are located above the subway.[33] Other stations are large facilities on the surface which also contain bus and/or streetcar platforms[28] to allow transfers to take place.[34]

Designs

The pre-1980 subway stations of the Bloor–Danforth line follow a two colour background and trim theme and use the unique Toronto Subway font on the stations' walls.[35] The tiling theme was influenced by the Broad Street Subway in Philadelphia and used a cycle that was similar to the design employed on the Yonge subway.[36] This design consists of two colours for the tiles, one for main wall tiles and another for trim tiles near the ceiling of the stations. The station names on the main wall tiles use the colour of the trim tiles and vice versa, except that some of the station names of the trim tiles are white instead of the main wall tile colour for readability.[37]

This pattern is based on a design similar to the stations along the University line which follow a regular pattern with some small variances which are the results of multiple events.[37] One of these tiling variances is located at Christie station, where some of the original tiles were replaced following the 1976 arson attack. The replacement trim tiles were differently coloured due to the lack of extra green trim tiles.[25]

Other variations to the pattern can be observed at Islington and Warden stations, which both have a tricolour design. The current terminus stations of Kipling and Kennedy stations resemble the second version of Union subway station. Since opening, Kipling and Kennedy stations are the only Bloor–Danforth line stations not to use the Toronto Subway font.[37]

Station modernization program

As the stations on the line have begun to show signs of aging, the TTC has embarked on a station modernization program aimed at improving accessibility and appearances at several subway stations. These modernizations include new and updated wall finishes, signage, lighting and public art, as well as the installation of elevators for accessibility needs. Pape and Dufferin stations are the first slated for modernization under this project, and Islington will also be modernized under larger capital projects aimed at greater accessibility and reconstruction of bus loading platforms.[27][38] Construction of a second access route at Broadview station was completed in 2007. This work provided direct access to bus platforms and a new streetcar platform, improving traffic control within the station.[28] Victoria Park's modernization project was completed between 2008 and 2011 to make the station more functional, attractive, better connected to the surrounding community, and fully accessible.

The second exit program was also included in station modernization projects after a fire safety audit revealed several at-risk stations with only one means of access and egress from the subway platform level to the street.[39] Some stations with only one entrance/exit received a second means of access/egress during major overhauls at stations such as Pape[40] and Dufferin.[41] Other stations such as Donlands and Greenwood are scheduled to receive second exits for egress only. Due to the potential for land expropriation and construction of the exit structures in residential neighbourhoods, this portion of the program has become controversial, as some houses need to be removed to accommodate these secondary exits.[42] However, plans to add a second exit for Donlands, Greenwood, and Woodbine stations have been deferred since late February 2011, due to lack of funding.[43]

Fare collection

The Bloor–Danforth line accepts and sells all types of fares at each of the collector booths in the subway stations. In addition to this, tokens and passes are also sold from terminals, which can be used at collector booths or be used to operate the automatic entrances.[44] The Presto smartcard can also be used to buy a fare at several stations,[45] while debit machines are being added to make it easier to purchase passes.[46]

All stations except Chester connect to surface TTC bus and/or streetcar routes during regular operating hours. Such connections involve a transfer, which is a free supplementary ticket, obtained at the point of entering the transit system, allowing the rider to transfer to another route,[47] or a fare-paid terminal, which is an area within an interchange only accessible to holders of valid tickets or tokens.[34]

Service frequency

The frequency for this line is 2–3 minutes during peak periods and 4–5 minutes during off-peak periods.

The 300 Bloor–Danforth bus provides late-night service to the area around the stations when the subway is not in operation. This service operates frequently along Bloor Street and Danforth Avenue between East/West Mall and Kennedy Stn via Danforth Road, Brimley Road, Eglinton Avenue East, North/South Service Road, Transway Crescent and Kennedy Road. On Sundays, these routes operate through the early morning hours, because the subway starts at 9:00 a.m. instead of the usual 6:00 a.m.[5] Frequency is 6–30 minutes.

Capacity

As of 2016, Line 2 was running at capacity with almost 26,000 peak-hour riders. Upgraded signalling would allow for more frequent trains and expand peak-hour capacity to almost 33,000 riders by 2031.[48]

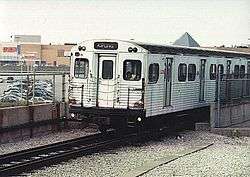

Rolling stock

The first trains to operate on the Bloor–Danforth line were the M-1 series subway trains, which were among the first subway trains to be manufactured in Canada.[49] At the time of construction, these subway cars were the longest in the world.[50] As a result of camshaft propulsion controls,[51] the increased speed provided by the M-series trains and the H-series trains allowed the Bloor–Danforth line to operate efficiently between Islington and Warden without the need for a larger subway fleet. As a result, the G-series subway trains were exclusively confined to the Yonge–University line. In the 1980s, as the H-series trains took over, the M-series trains were only used during rush hour as the trains were linked to be made up of vehicles of a single class.[49] With the introduction of the T-1 series subway trains (which had been used exclusively on the Yonge–University–Spadina line during their first years of service in the late 1990s), the M-1 series trains were retired from service between 1998 and 1999.[52]

Due to the opening of the Bloor–Danforth line and the additional services that were required, a new set of trains were purchased from the Hawker Siddeley group. These trains, which were a part of the H-series, were similar to the M-1 series trains with newer features such as electrically operated doors.[53] With the introduction of the T-1 series subway trains, the H-1 and H-2 subway trains were retired from service, while the remaining H-4 trains (along with some earlier T-1 series trains) were shifted to the Bloor–Danforth line.[54]

Following the introduction of the Toronto Rocket subway trains on the Yonge–University–Spadina and Sheppard lines, all of the T-1 series trains were transferred to the Bloor–Danforth line where they replaced the remaining H-4 and H-6 series subway trains. The T-1s are now the only trains operating on the line.[55] The remaining H-4 trains were retired from revenue service throughout the fall of 2011, and the last cars were decommissioned on January 27, 2012. They were the last version of TTC trains that were not equipped with air-conditioning systems (but instead used ceiling fans); they were also the last of which to be outfitted with larger orange upholstered bench seating and were mainly used on weekdays, most often during rush hour several years before their retirement. The H-4s also had a similar interior design based from the H-2 subway cars. The H-6 series trains (which had bright orange doors and panels, individual seats, along with light brown floors, cream walls and brown simulated wood grain panels) were retired from service between 2013 and 2014; the final run for the last H-6 series train took place on June 20, 2014. In the summer of 2016, a few TR trains were used on Line 2 because of the poor air conditioning in the T1's combined with a very warm summer.

Depot

The trains that serve the Bloor–Danforth line are stored at the Greenwood Subway Yard, which opened with the first segment of the line. Before the yard was built, the land was occupied by a quarry and a garbage dump. Due to its location next to the Canadian National Railway tracks, it was possible for trains to be delivered directly to the subway.[56] The CN rail tracks were converted to allow for the storage of more subway trains as the T-1 series trains were shifted from Yonge–University-Spadina line to the Bloor–Danforth line.[57] In addition to providing storage for subway trains, the Greenwood yard is also used to maintain vehicles, which operate on Line 3 Scarborough as the McCowan RT Yard is only equipped for vehicle storage and to perform basic maintenance of vehicles.[56]

Before the opening of the Wilson Subway Yard, many excess train-sets were stored at the Vincent Subway Yard, which is located between Keele station and Dundas West station. Although this facility did not have maintenance facilities, there was still enough space for the storage and cleaning of subway trains. While it is not an active subway yard, it is used to store subway work vehicles.[58]

Expansion plans

Scarborough Subway Extension

The Scarborough Subway Extension (SSE) is a proposal to replace the Scarborough RT with an eastward extension of the Bloor-Danforth line.

Earlier history

In 1983, there was discussion of a rapid transit extension from Kennedy to Scarborough City Centre. As multiple types of technologies were examined many politicians requested a subway extension instead of the then proposed streetcar line. Instead, a medium-capacity rail transport system, known as the Scarborough RT was built.[59]

In 2005, Toronto City Council again proposed to extend the line northeastward as a replacement for the aging Scarborough RT. In 2006, this proposal was then altered when Scarborough councillors agreed to support plans to refurbish the existing line using other light-metro options for Scarborough. Using heavy-rail rapid transit like the rest of the Toronto subway in Scarborough was not yet examined.[60] In 2007, mayor David Miller included the refurbishment of the Scarborough RT using modern light rait transit as part of his Transit City plan.

During his 2010 mayoralty campaign, Rob Ford denounced the idea of light rail transit and instead proposed to replace the Scarborough RT with an extension of the Bloor–Danforth line.[61] However, on March 31, 2011, Ford agreed with the provincial government that the province's Metrolinx agency would replace the Scarborough RT with an elevated light rail line as part of a proposed "Eglinton-Scarborough Crosstown line" instead.[62] In June 2012, the idea of a Scarborough subway extension was a key part of Toronto's proposed OneCity transit plan. This plan was later rejected by the provincial government and Mayor Rob Ford.[63]

Three-stop proposal

On September 4, 2013, the province of Ontario announced that it would fund two-thirds of the 6.4 kilometres (4.0 mi) extension of the Bloor-Danforth line from Kennedy to Scarborough City Centre at Scarborough Centre station.[64] The federal government of Canada would fund the remaining one-third. Toronto City Council approved the extension by a vote of 24–20 on October 8, 2013. The subway route would extend eastward towards McCowan Road, via Eglinton Avenue and Danforth Road, and proceeding north towards the intersection of McCowan Road and Sheppard Avenue, via Scarborough City Centre. There would be three new stations at Lawrence Avenue East, Scarborough Town Centre and Sheppard Avenue East. The city would also raise property taxes annually over the next three years. Digging of the extension was expected to begin as early as 2018, with a completion within five years.[65][66]

In December 2014, Councillor Glenn De Baeremaeker, one of the city's deputy mayors, proposed a fourth stop along the Scarborough subway extension, at Danforth Road and Eglinton Avenue to reduce the station spacing between Kennedy Station and the next stop from about 4 km (2.5 mi) to 2 km (1.2 mi). At that time, he was told the extra station would add $100 million to $150 million to the cost of the extension.[67]

However, a subsequent city staff report indicated that the proposed stations at Lawrence and Sheppard avenues had "little development potential" nearby and were too close to planned SmartTrack stations.[68]

One-stop proposal

| Scarborough Subway Extension | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Legend | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

On January 20, 2016, City Staff issued a proposal to eliminate two of the three stops on the planned Scarborough Subway Extension and to terminate Line 2 Bloor–Danforth at Scarborough Town Centre. The planned intermediate stop at Lawrence Avenue would be eliminated along with the proposed stretch to Sheppard Avenue. This revised plan would prevent the subway from competing for ridership with SmartTrack's branch to Markham.[69] Also, the proposed change was to reduce the cost of the extension from $3.5 billion to $2.5 billion, where the $1 billion saved would be used to extend Line 5 Eglinton east- and northwards to the University of Toronto Scarborough Campus.[70][68][71] (However, most of the $1 billion saved was subsequently diverted back to the SSE to cover additional estimated construction costs for the one-stop subway.)[72]

City planning staff estimate that the peak ridership of the one-stop extension to be 7,300 in the peak hour and peak direction, about half of the 15,000 peak ridership considered the low end to justify a subway. With the original three-stop extension, the peak ridership estimate was 9,500 to 14,000; however, that estimate was reduced to 7,300 because of competition from the proposed SmartTrack and by the elimination of two of the three original stops. Mayor John Tory and Scarborough Councillor Glenn De Baeremaeker say a peak ridership of 7,300 would still be acceptable as it is still greater than the 6,000 peak at terminal station Kipling.[73] However, a Toronto Star article points out there is only one station within 6 kilometres of Scarborough Town Centre but more stations are within 6 kilometres of other terminal stations to boost ridership. The SSE would carry an estimate 31,000 riders per day as compared to 66,355 riders from Kipling to Jane (five stations) and 96,660 riders from Finch to York Mills (four stations). The SSE performs better in ridership only against the terminal of the underperforming Line 4 Sheppard line.[48]

A one-stop SSE would attract an estimated 4,500 new riders to the TTC system.[74]

In June 2016, the estimated cost of the one-stop SSE was revised from $2 billion to $2.9 billion because tunnels need to be deeper than expected in some places, with the new terminal station being 45 to 90 per cent deeper. An additional cost factor is that a high water table would require more concrete.[75] There is also a $300 million maintenance cost to keep the Scarborough RT operating until the SSE's opening resulting in a total project cost of $3.2 billion.[76]

The project is funded with an estimated completion in late 2025.[77] As of October 2016, the alignment of the SSE had not yet been finalized. The City prefers a McCowan Road alignment. However, because of rising costs for that alignment, alignments along either Midland Avenue or Brimley Road are being considered.[76]

According to transit advocate Steve Munro, the SSE will be built to use only Automatic Train Control. Thus, the SSE's opening would force the early retirement of all T1 subway cars on line 2 as it would be too expensive to convert T1 cars to ATC.[78]

West to Mississauga

The TTC's Rapid Transit Expansion Study, published in 2001, identified three possible western extensions to the line. The first was a 3.2-kilometre (2.0 mi) link to Sherway Gardens, with a station added at the East Mall at a later date. The second included an additional 1.4 kilometres (0.87 mi) from Sherway Gardens to Dixie Road, while a further section from Dixie Road to Mississauga City Centre, which included three stations, was considered but rejected due to cost and planning considerations.[79] This was replaced by a planned Dundas LRT run by MiWay going from Kipling to Hurontario Street, linking to the planned Hurontario LRT as part of the MoveOntario 2020 transit plan.[80] This plan was revived, along with the Jane LRT, the Finch West LRT extensions, the Waterfront LRTs, and others, by the "Feeling Congested?" report by the City of Toronto in 2013, as a "Unfunded Future Rapid Transit Project" - which means it will be constructed sometime in the future.[1]

See also

References

- 1 2 http://www.toronto.ca/legdocs/mmis/2013/pg/bgrd/backgroundfile-64550.pdf

- 1 2 "Toronto Transit Commission Subway ridership, 2011-2012" (PDF). Toronto Transit Commission. Retrieved November 28, 2012.

- 1 2 "Subway". Schedules & Maps. Toronto Transit Commission. Retrieved January 2015.

Line 2 Bloor-Danforth has 31 stations

Check date values in:|access-date=(help) - 1 2 3 Dewees, D.N. (2004). "The effect of a subway on residential property values in Toronto". Journal of Urban Economics. 3 (4): 357–369. doi:10.1016/0094-1190(76)90035-8.

- 1 2 "Blue Night Network Map" (PDF). Toronto Transit Commission. Retrieved July 31, 2012.

- ↑ TTC tests new numerical signage system

- ↑ "New TTC Signage at Eglinton Station".

- ↑ Toronto Transit Commission, Scheduled Service Summary, Board Period Commencing Sunday, July 21, 1991

- ↑ "Subway/RT Information". Toronto Transit Commission. Retrieved February 19, 2012.

- ↑ Osbaldeston, Mark (2008). Unbuilt Toronto: a history of the city that might have been. Dundurn Press. ISBN 1-55002-835-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Filey, Mike (1996). TTC Story: The First Seventy-Five Years. Dundurn Press. p. 111. ISBN 1-55002-244-X.

- ↑ "Early Subway Proposals". Transit Toronto. November 10, 2006. Retrieved July 31, 2012.

- ↑ "A History of Subways on Bloor and Queen Streets". Transit Toronto. November 29, 2009. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ↑ "A History of the Original Yonge Subway". Transit Toronto. April 21, 2012. Retrieved July 31, 2012.

- ↑ Kaplan, Harold (1967). "The Toronto Transit Commission: A Case Study of the Structural-Functional Approach to Administrative Organizations". The Canadian Journal of Economics and Political Science. Blackwell Publishing. 33 (2): 171–189. doi:10.2307/139770. JSTOR 139770.

- ↑ Filey 1996, pp. 110–111

- ↑ "Land Use Planning - Ontario Municipal Board". Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing. Retrieved July 31, 2012.

- ↑ Filey 1996, p. 110

- ↑ "The Abandoned Streetcar Shuttle Connection Passages". Transit Toronto. November 10, 2006. Retrieved May 10, 2008.

- ↑ Filion, Pierre (200). "Balancing concentration and dispersion? Public policy and urban structure in Toronto". Environment and Planning - Part C. Pion. 18 (2): 163–189. doi:10.1068/c2m.

- ↑ Munro, Steve (March 14, 2006). "The Bloor-Danforth Subway 40 Years After Opening. Why Was It So Successful?" (PDF). Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ↑ Mees, Paul (2010). Transport For Suburbia: Beyond The Automobile Age. New York, New York: Earthscan. ISBN 978-1-84407-740-3.

- ↑ Frisken, Frances. "Toronto at A Crossroads, and How It Got Here" (PDF). The World Bank Group. p. 11. Retrieved April 6, 2012.

- ↑ "A history of fares on the TTC". Transit Toronto. April 21, 2012.

- 1 2 Erret, Joshua (November 16, 2005). "At Christie, It's Two-Parts Escalator and One-Part Stairs". Torontoist. Retrieved April 5, 2012.

- ↑ "Station Modernization Program Funding Status". Toronto Transit Commission. September 19, 2007. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- 1 2 "Service Advisories - Pape Station". Toronto Transit Commission. Retrieved 2012-02-19.

- 1 2 3 Munro, Steve (December 18, 2007). "Broadview Station: The End Is Nigh?". Archived from the original on 2015-03-04. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- ↑ White, Craig (August 5, 2010). "Kipling Subway Station's East Entrance On Its Way". urbantoronto.ca. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ↑ "Subway/RT Map". Toronto Transit Commission. Retrieved July 31, 2012.

- ↑ Transit stations, Metropolitan Toronto [cartographic material] / Metro Corporate and Human Resources (Map). 1:62,500. North York : Metro Corporate and Human Resources. April 1996.

- ↑ "Bloor-Danforth Subway Line". Balance for Blind Adults. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- ↑ "Finding Us Line". Bloor-Yorkville BIA. Retrieved August 3, 2012.

- 1 2 "Paying the Fare". Toronto Transit Commission. Retrieved August 1, 2012.

- ↑ LeBlanc, Dave (March 25, 2005). "'Subway Chic' Inspires Graphic Designers". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved April 5, 2012.

- ↑ Brader, Mark (January 10, 2008). "An Essay on Original Subway Station Design". Transit Toronto. Retrieved July 28, 2012.

- 1 2 3 Blackett, Matthew (March 25, 2008). "Ride the Rainbow of the Bloor-Danforth". Spacing Toronto. Retrieved April 5, 2012.

- ↑ "Service Advisories - Dufferin Station Modernization". Toronto Transit Commission. Retrieved February 19, 2012.

- ↑ "Real Estate Acquisitions – TTC Woodbine Station –Easier Access and Second Exit Program" (PDF). City of Toronto. July 28, 2010. Retrieved June 21, 2012.

- ↑ "Pape Station Modernization Project". Toronto Transit Commission. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ↑ "Dufferin Station Modernization Project". Toronto Transit Commission. 2010. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- ↑ Vyhnak, Carola (June 29, 2010). "Residents protest demolishing homes for subway exits". The Star. Toronto.

- ↑ Goddard, John (March 2, 2011). "TTC slams door on second exit at Donlands subway". Toronto Star. Toronto. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- ↑ "Buying Tickets, Tokens and Passes". Toronto Transit Commission. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ↑ "TTC PRESTO Fare System". Toronto Transit Commission. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ↑ Kretzel, Lasia (July 5, 2012). "TTC set to spend $570K to put debit machines in collector booths". The National Post. Retrieved July 6, 2012.

- ↑ "Transfers". Toronto Transit Commission. Retrieved June 25, 2012.

- 1 2 Jennifer Pagliaro & Ben Spurr (16 June 2016). "Putting Scarborough subway claims to the test". Toronto Star. Retrieved 2016-06-16.

- 1 2 "The Montreal Series (M-1) Cars (1963–1999)". Transit Toronto. February 16, 2011. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

- ↑ "Toronto Transit Commission 5300–5301". Halton County Radial Railway. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

- ↑ Muc, A.M. "Electromagnetic Fields Associated With Transportation Systems" (PDF). Radiation Health and Safety Consulting. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

- ↑ "Montreal Series Retirement Charter - February 28, 1999". Transit Toronto. February 16, 2011. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

- ↑ "The Camshaft Control Hawkers (Series H1, H2, H3 and H4)". Transit Toronto. June 16, 2012. Retrieved June 27, 2012.

- ↑ "The T-1 (Toronto) Series Cars (1997-?)". Transit Toronto. March 4, 2012. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- ↑ Munro, Steve (January 26, 2012). "Goodbye to the H4 Trains". Archived from the original on 2015-03-04. Retrieved June 28, 2012.

- 1 2 "The Greenwood Subway Yards". Transit Toronto. June 7, 2011. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- ↑ "Chief Executive Officer's Report (April 1 - April 28, 2012)" (PDF). Toronto Transit Commission. June 29, 2012. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- ↑ "The Vincent Subway Yards". Transit Toronto. November 10, 2006. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- ↑ Filey 1996, p. 137

- ↑ York University (August 29, 2006). "Three 'model schools' reimagine their role with York's help". YFile. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- ↑ "Rob Ford: 'Transit City is over'". CBC News. December 1, 2010. Archived from the original on December 5, 2010.

- ↑ "Ontario And Toronto Moving Forward On Public Transit". Ontario Newsroom. March 31, 2011.

- ↑ "Toronto's OneCity transit plan rejected by province". CBC News. June 29, 2012. Retrieved July 7, 2012.

- ↑ "Province To Extend Bloor-Danforth Subway Line". MTO. September 4, 2013. Retrieved September 4, 2013.

- ↑ Scarborough subway route still in debate

- ↑ City Council votes in favour of Scarborough subway

- ↑ Daniel Dale (December 13, 2014). "Deputy Mayor Glenn De Baeremaeker wants to change Scarborough subway plan". Toronto Star. Retrieved 2015-11-20.

- 1 2 Chris Fox (21 January 2016). "New plan for Scarborough subway will allow city to 'get on' with project: Tory". CablePulse 24. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- ↑ Jennifer Pagliaro (20 January 2016). "New Scarborough transit plan 'buys peace in the land'". Toronto Star. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ↑ Oliver Moore and Marcus Gee (20 January 2016). "Scarborough subway would shrink under plan to extend Eglinton Crosstown". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

- ↑

- ↑ Oliver Moore (13 July 2016). "Toronto City Council approves planning for raft of transit projects". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2016-07-14.

- ↑ Ben Spurr, Transportation Reporter & Jennifer Pagliaro, City Hall reporter (1 June 2016). "Mayor Tory defends Scarborough subway extension despite new ridership data". Toronto Star. Retrieved 2016-06-01.

- ↑ Edward Keenan, Columnist (2 June 2016). "Priority should be alternative transit routes into downtown: Keenan". Toronto Star. Retrieved 2016-06-05.

- ↑ Oliver Moore (17 June 2016). "Scarborough subway cost rises by $900-million". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 2016-06-17.

- 1 2 Ben Spurr (5 October 2016). "Scarborough subway might already be off track". Toronto Star. Retrieved 2016-10-05.

- ↑ Ben Spurr & Jennifer Pagliaro (26 June 2016). "Mayor John Tory's transit priorities face financial, political challenge: analysis". Toronto Star. Retrieved 2016-07-20.

- ↑ Steve Munro (4 October 2016). "TTC Capital Program Review". Retrieved 2016-10-05.

- ↑ Toronto Transit Commission (August 2001). "Rapid Transit Expansion Study" (PDF). pp. 8–9. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- ↑ City of Missisauga (March 14, 2012). "Hurontario-Main LRT Project" (PDF). Retrieved July 31, 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Bloor Danforth line. |

- TTC subway web page

- Transit Toronto: A history of subways on Bloor and Queen Streets

- Scarborough Subway Extension website

_(14918534190).jpg)