Aneurysmal bone cyst

| Aneurysmal bone cyst | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | rheumatology |

| ICD-10 | M85.5 |

| ICD-9-CM | 733.22 |

| OMIM | 606179 |

| eMedicine | radio/26 article/1254784 |

| MeSH | D017824 |

Aneurysmal bone cyst, abbreviated ABC, is an osteolytic bone neoplasm characterized by several sponge-like blood or serum filled, generally non-endothelialized spaces of various diameters.[1]

Etymology

The term is a misnomer, as the lesion is neither an aneurysm nor a cyst.[1]

Causes

Aneurysmal bone cyst has been widely regarded a reactive process of uncertain etiology since its initial description by Jaffe and Lichtenstein in 1942. Many hypotheses have been proposed to explain the etiology and pathogenesis of aneurysmal bone cyst, and until very recently the most commonly accepted idea was that aneurysmal bone cyst was the consequence of an increased venous pressure and resultant dilation and rupture of the local vascular network. However, studies by Panoutsakopoulus et al. and Oliveira et al. uncovered the clonal neoplastic nature of aneurysmal bone cyst. Primary etiology has been regarded arteriovenous fistula within bone.[2]

The lesion may arise de novo or may arise secondarily within a pre-existing bone tumor, because the abnormal bone causes changes in hemodynamics. An aneurysmal bone cyst can arise from a pre-existing chondroblastoma, a chondromyxoid fibroma, an osteoblastoma, a giant cell tumor, or fibrous dysplasia. A giant cell tumor is the most common cause, occurring in 19% to 39% of cases. Less frequently, it results from some malignant tumors, such as osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, and hemangioendothelioma.

Pathology

Histologically, they are classified in two variants.

- The classic (or standard) form (95%) has blood filled clefts among bony trabeculae. Osteoid tissue is found in stromal matrix.

- The solid form (5%) shows fibroblastic proliferation, osteoid production and degenerated calcifying fibromyxoid elements.

According to Buraczewski and Dabska, the development of the aneurysmal bone cyst follows three stages.[1]

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Initial phase (I) | Osteolysis without peculiar findings |

| Growth phase (II) |

|

| Stabilization phase (III) | Fully developed radiological pattern |

They can also be associated with a TRE17/USP6 translocation.[3]

Aneurysmal bone cysts may be intraosseous, staying inside of the bone marrow. Or they may be extraosseous, developing on the surface of the bone, and extending into the marrow. A radiograph will reveal a soap bubble appearance.

Clinical features

The afflicted may have relatively small amounts of pain that will quickly increase in severity over a time period of 6–12 weeks. The skin temperature around the bone may increase, a bony swelling may be evident, and movement may be restricted in adjacent joints.[4]

Spinal lesions may cause quadriplegia and patients with skull lesions may have headaches.

Sites

Commonly affected sites are metaphyses of vertebra, flat bones, femur and tibia.[5] Approximate percentages by sites are as shown:

- Skull and mandible (4%)

- Spine (16%)

- Clavicle and ribs (5%)

- Upper extremity (21%)

- Pelvis and sacrum (12%)

- Femur (13%)

- Lower leg (24%)

- Foot (3%)

Diagnosis

On a radiograph, well-defined, expansile, lytic lesion is observed. Expansion of cortex gives the lesion a balloon-like appearance. Larger lesions may appear septated[6]

Differential diagnosis

Following conditions are excluded before diagnosis can be confirmed:[7]

- Unicameral bone cyst

- Giant cell tumor

- Telangiectatic osteosarcoma

- Secondary aneurysmal bone cyst

Treatment

Curettage is performed on some patients,[8] and is sufficient for inactive lesions. The recurrence rate with curettage is significant in active lesions, and marginal resection has been advised. Liquid nitrogen, phenol, methyl methacrylate are considered for use to kill cells at margins of resected cyst.[2]

Prognosis

Recurrence rate of solid form of tumour is lower than classic form.[2]

Epidemiology

It is common in age group of 10–30 years.[6] It is second most common tumor of spine and commonest benign tumor of pelvis in pediatric population.[2] Incidence is slightly more in males than females (1.3:1).[7]

Additional images

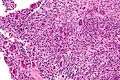

-

High magnification micrograph of an aneurysmal bone cyst

-

Intermediate magnification micrograph of an aneurysmal bone cyst

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Maroldi, Roberto (2005). Imaging in Treatment Planning for Sinonasal Diseases. Springer. p. 114. ISBN 9783540266310.

- 1 2 3 4 Pediatric Orthopedics in Practice. Springer. 2007. pp. 151–155. ISBN 9783540699644.

- ↑ Ye Y, Pringle LM, Lau AW, et al. (June 2010). "TRE17/USP6 oncogene translocated in aneurysmal bone cyst induces matrix metalloproteinase production via activation of NF-kappaB". Oncogene. 29 (25): 3619–29. doi:10.1038/onc.2010.116. PMC 2892027

. PMID 20418905.

. PMID 20418905. - ↑ Zadik, Yehuda; Aktaş Alper; Drucker Scott; Nitzan W Dorrit (2012). "Aneurysmal bone cyst of mandibular condyle: A case report and review of the literature". J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 40 (8): e243–8. doi:10.1016/j.jcms.2011.10.026. PMID 22118925.

- ↑ Rosai and Ackerman's surgical pathology, Volume 2, 9th ed. Mosby. 2004. p. 148. ISBN 9780323013420.

- 1 2 Davies, Arthur (2002). Who Manual Of Diagnostic Imaging: Radiographic Anatomy And Interpretation Of The Muskuloskeletal System, VOlume. World Health Organization. pp. 168–186. ISBN 9241545550.

- 1 2 Differential Diagnosis in Surgical Pathology: Expert Consult - Online and Print, 2e. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2010. pp. 878–879. ISBN 9781416045809.

- ↑ Mankin HJ, Hornicek FJ, Ortiz-Cruz E, Villafuerte J, Gebhardt MC (September 2005). "Aneurysmal bone cyst: a review of 150 patients". J. Clin. Oncol. 23 (27): 6756–62. doi:10.1200/JCO.2005.15.255. PMID 16170183.

Missing references