Branching process

In probability theory, a branching process is a Markov process that models a population in which each individual in generation n produces some random number of individuals in generation n + 1, according, in the simplest case, to a fixed probability distribution that does not vary from individual to individual.[1] Branching processes are used to model reproduction; for example, the individuals might correspond to bacteria, each of which generates 0, 1, or 2 offspring with some probability in a single time unit. Branching processes can also be used to model other systems with similar dynamics, e.g., the spread of surnames in genealogy or the propagation of neutrons in a nuclear reactor.

A central question in the theory of branching processes is the probability of ultimate extinction, where no individuals exist after some finite number of generations. It is not hard to show that, starting with one individual in generation zero, the expected size of generation n equals μn where μ is the expected number of children of each individual. If μ < 1, then the expected number of individuals goes rapidly to zero, which implies ultimate extinction with probability 1 by Markov's inequality. Alternatively, if μ > 1, then the probability of ultimate extinction is less than 1 (but not necessarily zero; consider a process where each individual either has 0 or 100 children with equal probability. In that case, μ = 50, but probability of ultimate extinction is greater than 0.5, since that's the probability that the first individual has 0 children). If μ = 1, then ultimate extinction occurs with probability 1 unless each individual always has exactly one child.

In theoretical ecology, the parameter μ of a branching process is called the basic reproductive rate.

Mathematical formulation

The most common formulation of a branching process is that of the Galton–Watson process. Let Zn denote the state in period n (often interpreted as the size of generation n), and let Xn,i be a random variable denoting the number of direct successors of member i in period n, where Xn,i are independent and identically distributed random variables over all n ∈{ 0, 1, 2, ...} and i ∈ {1, ..., Zn}. Then the recurrence equation is

with Z0 = 1. Alternatively, one can formulate a branching process as a random walk. Let Si denote the state in period i, and let Xi be a random variable that is iid over all i. Then the recurrence equation is

with S0 = 1. To gain some intuition for this formulation, one can imagine a walk where the goal is to visit every node, but every time a previously unvisited node is visited, additional nodes are revealed that must also be visited. Let Si represent the number of revealed but unvisited nodes in period i, and let Xi represent the number of new nodes that are revealed when node i is visited. Then in each period, the number of revealed but unvisited nodes equals the number of such nodes in the previous period, plus the new nodes that are revealed when visiting a node, minus the node that is visited. The process ends once all revealed nodes have been visited.

Extinction problem

The ultimate extinction probability is given by

For any nontrivial cases (trivial cases are ones in which the probability of having no offspring is zero for every member of the population - in such cases the probability of ultimate extinction is 0), the probability of ultimate extinction equals one if μ ≤ 1 and strictly less than one if μ > 1.

The process can be analyzed using the method of probability generating function. Let p0, p1, p2, ... be the probabilities of producing 0, 1, 2, ... offspring by each individual in each generation. Let dm be the extinction probability by the mth generation. Obviously, d0= 0. Since the probabilities for all paths that lead to 0 by the m-th generation must be added up, the extinction probability is nondecreasing in generations. That is,

Therefore, dm converges to a limit d, and d is the ultimate extinction probability. If there are j offspring in the first generation, then to die out by the mth generation, each of these lines must die out in m-1 generations. Since they proceed independently, the probability is (dm−1)j. Thus,

The right-hand side of the equation is probability generating function. Let h(z) be the ordinary generating function for pi:

Using the generating function, the previous equation becomes

Since dm → d, d can be found by solving

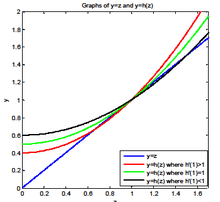

This is also equivalent to finding the intersection point(s) of lines y = z and y = h(z) for z ≥ 0. y = z is a straight line. y = h(z) is an increasing (since ) and convex (since ) function. There are at most two intersection points. Since (1,1) is always an intersect point for the two functions, there only exist three cases:

Case 1 has another intersect point at z < 1 (see the red curve in the graph).

Case 2 has only one intersect point at z = 1.(See the green curve in the graph)

Case 3 has another intersect point at z > 1.(See the black curve in the graph)

In case 1, the ultimate extinction probability is strictly less than one. For case 2 and 3, the ultimate extinction probability equals to one.

By observing that h′(1) = p1 + 2p2 + 3p3 + ... = μ is exactly the expected number of offspring a parent could produce, it can be concluded that for a branching process with generating function h(z) for the number of offspring of a given parent, if the mean number of offspring produced by a single parent is less than or equal to one, then the ultimate extinction probability is one. If the mean number of offspring produced by a single parent is greater than one, then the ultimate extinction probability is strictly less than one.

Size dependent branching processes

Along with discussion of a more general model of branching processes known as age-dependent branching processes by Grimmett,[2] in which individuals live for more than one generation, Krishna Athreya has identified three distinctions between size-dependent branching processes which have general application. Athreya identifies the three classes of size-dependent branching processes as sub-critical, stable, and super-critical branching measures. For Athreya, the central parameters are crucial to control if sub-critical and super-critical unstable branching is to be avoided.[3] Size dependent branching processes are also discussed under the topic of resource-dependent branching process [4]

Example of extinction problem

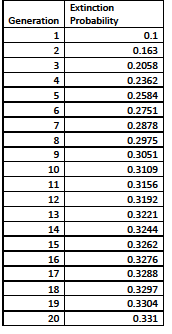

Consider a parent can produce at most two offspring and the probabilities for the number produced are p0 = 0.1, p1 = 0.6, and p2 = 0.3. The extinction probability in each generation is

with d0 = 0. Here, the extinction probability is calculated from generation 1 to generation 20. The result is shown in the table.

For the ultimate extinction probability, we need to find d which satisfies d = p0 + p1d + p2d2. In this example, d = 1/3. This is exactly what the probabilities in the table converges to.

See also

- Galton–Watson process

- Random tree

- Branching random walk

- Bruss-Duerinckx Theorem

- Martingale (probability theory)

References

- ↑ Athreya, K. B. (2006). "Branching Process". Encyclopedia of Environmetrics. doi:10.1002/9780470057339.vab032. ISBN 0471899976.

- ↑ G. R. Grimmett and D. R. Stirzaker, Probability and Random Processes, 2nd ed., Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1992.

- ↑ Krishna Athreya and Peter Jagers. Branching Processes. Springer. 1973.

- ↑ F. Thomas Bruss and M. Duerinckx (2015) "Resource dependent branching processes and the envelope of societies", Annals of Applied Probability. 25: 324–372.

- C. M. Grinstead and J. L. Snell, Introduction to Probability, 2nd ed. Section 10.3 discusses branching processes in detail together with the application of generating functions to study them.

- G. R. Grimmett and D. R. Stirzaker, Probability and Random Processes, 2nd ed., Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1992. Section 5.4 discusses the model of branching processes described above. Section 5.5 discusses a more general model of branching processes known as age-dependent branching processes, in which individuals live for more than one generation.