Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628

| Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Byzantine–Sasanian wars | |||||||||

Battle between Heraclius' army and Persians under Khosrau II. Fresco by Piero della Francesca, c. 1452 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

Byzantine Empire, Western Turkic Khaganate Arab tribes loyal to Heraclius |

Sasanian Empire, Avars (and Slavic allies) Principate of Iberia Jewish and Samaritan rebels (c. 614) Arab tribes loyal to Khosrau | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Phocas, Philippicus, Germanus †, Leontius, Domentziolus, Priscus, Heraclius, Nicetas, Theodore, Bonus, Ziebel, Shahrbaraz (after 626),[1] Kardarigan (after 626) |

Khosrau II, Shahrbaraz (602-626), Shahin, Kardarigan (602-626), Shahraplakan, Stephen I of Iberia †, Rhahzadh †, Unnamed Avar khagan, Datoyean, Dzuan Veh †, Ashtat Yeztayar, Senitam Khusro, Vahram-Arshusha V (POW) Benjamin of Tiberias | ||||||||

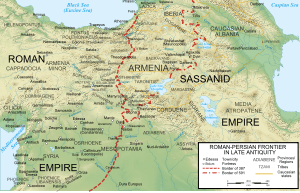

The Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 was the final and most devastating of the series of wars fought between the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire and the Sasanian Empire of Persia. The previous war between the two powers had ended in 591 after Emperor Maurice helped the Sasanian king Khosrau II regain his throne. In 602 Maurice was murdered by his political rival Phocas. Khosrau proceeded to declare war, ostensibly to avenge the death of Maurice. This became a decades-long conflict, the longest war in the series, and was fought throughout the Middle East and eastern Europe: in Egypt, the Levant, Mesopotamia, the Caucasus, Anatolia, Armenia and even before the walls of Constantinople itself.

While the Persians proved largely successful during the first stage of the war from 602 to 622, conquering much of the Levant, Egypt, and parts of Anatolia, the ascendancy of emperor Heraclius in 610 led, despite initial setbacks, to the Persians' defeat. Heraclius' campaigns in Persian lands from 622 to 626 forced the Persians onto the defensive, allowing his forces to regain momentum. Allied with the Avars and Slavs, the Persians made a final attempt to take Constantinople in 626, but were defeated there. In 627 Heraclius invaded the heartland of the Persians and forced them to sue for peace.

By the end of the conflict both sides had exhausted their human and material resources. Consequently, they were vulnerable to the sudden emergence of the Islamic Rashidun Caliphate, whose forces invaded both empires only a few years after the war. The Muslim forces swiftly conquered the entire Sasanian Empire and deprived the Byzantine Empire of its territories in the Levant, the Caucasus, Egypt, and North Africa. Over the following centuries, half the Byzantine Empire and the entire Sasanian Empire came under Muslim rule.

Background

After decades of inconclusive fighting, Emperor Maurice ended the Byzantine–Sassanid War of 572–591 by helping the exiled Sassanid prince Khosrau, the future Khosrau II, to regain his throne from the usurper Bahrām Chobin. In return the Sassanids ceded to the Byzantines parts of northeastern Mesopotamia, much of Persian Armenia and Caucasian Iberia, though the exact details are not clear.[2][3][4] More importantly for the Byzantine economy, they no longer had to pay tribute to the Sassanids.b[›] Emperor Maurice then began new campaigns in the Balkans to stop incursions by the Slavs and Avars.[5][6]

The magnanimity and campaigns of emperor Tiberius II had eliminated the surplus in the treasury left from the time of Justin II.[7][8][9] In order to generate a reserve in the treasury, Maurice instituted strict fiscal measures and cut army pay; which led to four mutinies.[10] The final mutiny in 602 resulted from Maurice ordering his troops in the Balkans to live off the land during the winter.[11][12] The army proclaimed Phocas, a Thracian centurion, as emperor.[2][12][13] Maurice attempted to defend Constantinople by arming the Blues and the Greens - supporters of the two major chariot racing teams of the Hippodrome - but they proved ineffective. Maurice fled but was soon intercepted and killed by the soldiers of Phocas.[12][14][15][16]

Beginning of the conflict

Upon the murder of Maurice, Narses, governor of the Byzantine province of Mesopotamia, rebelled against Phocas and seized Edessa, a major city of the province.[17] Emperor Phocas instructed general Germanus to besiege Edessa, prompting Narses to request help from the Persian king Khosrau II. Khosrau, who was only too willing to help avenge Maurice, his "friend and father", used Maurice's death as an excuse to attack the Roman Empire, trying to reconquer Armenia and Mesopotamia.[18][19]

General Germanus died in battle against the Persians. An army sent by Phocas against Khosrau was defeated near Dara in Upper Mesopotamia, leading to the capture of that important fortress in 605. Narses escaped from Leontius, the eunuch appointed by Phocas to deal with him,[20] but when Narses attempted to return to Constantinople to discuss peace terms, Phocas ordered him seized and burned alive.[21] The death of Narses along with the failure to stop the Persians damaged the prestige of Phocas' military regime.[20][22]

Heraclius' rebellion

.jpg)

In 608, general Heraclius the Elder, Exarch of Africa, revolted, urged on by Priscus, the Count of the Excubitors and son-in-law of Phocas.[22][23] Heraclius proclaimed himself and his son of the same name as consuls—thereby implicitly claiming the imperial title—and minted coins with the two wearing the consular robes.[24]

At about the same time rebellions began in Roman Syria and Palaestina Prima in the wake of Heraclius' revolt. In 609 or 610 the Patriarch of Antioch, Anastasius II, died. Many sources claim that the Jews were involved in the fighting, though it is unclear where they were members of factions and where they were opponents of Christians.[25][26] Phocas responded by appointing Bonus as comes Orientis (Count of the East) to stop the violence. Bonus punished the Greens, a horse racing party, in Antioch for their role in the violence in 609.[25]

Heraclius the Elder sent his nephew Nicetas to attack Egypt. Bonus went to Egypt to try to stop Nicetas, but was defeated by the latter outside Alexandria.[25] In 610, Nicetas succeeded in capturing the province, establishing a power base there with the help of Patriarch John the Almsgiver, who was elected with the help of Nicetas.[27][28][29][30][31]

The main rebel force was employed in a naval invasion of Constantinople, led by the younger Heraclius, who was to be the new emperor. Organized resistance against Heraclius soon collapsed, and Phocas was handed to him by the patrician Probos (Photius).[32] Phocas was executed, though not before a celebrated exchange of comments between him and his successor:

"Is it thus", asked Heraclius, "that you have governed the Empire?"

"Will you," replied Phocas, with unexpected spirit, "govern it any better?"[33]

The elder Heraclius disappears soon afterward from sources, supposedly dying, though the date is unknown.[34]

After marrying his niece Martina and being crowned by the Patriarch, the 35-year-old Heraclius set out to perform his work as emperor. Phocas' brother, Comentiolus, commanded a sizable force in central Anatolia but was assassinated by the Armenian commander Justin, removing a major threat to Heraclius' reign.[28] Still, transfer of the forces commanded by Comentiolus had been delayed, allowing the Persians to advance further in Anatolia.[35] Trying to increase revenues and reduce costs, Heraclius limited the number of state-sponsored personnel of the Church in Constantinople by not paying new staff from the imperial fisc.[36] He used ceremonies to legitimize his dynasty,[37] and he secured a reputation for justice to strengthen his grip on power.[38]

Persian ascendancy

The Persians took advantage of this civil war in the Byzantine empire by conquering frontier towns in Armenia and Upper Mesopotamia.[39][40] Along the Euphrates, in 609, they conquered Mardin and Amida (Diyarbakır). Edessa, which some Christians are said to have believed would be defended by Jesus himself on behalf of King Abgar V of Edessa against all enemies, fell in 610.[22][40][41][42]

In Armenia, the strategically important city of Theodosiopolis (Erzurum) surrendered in 609 or 610 to Ashtat Yeztayar, because of the persuasion of a man who claimed to be Theodosius, the eldest son and co-emperor of Maurice, who had supposedly fled to the protection of Khosrau.[41][43] In 608, the Persians launched a raid into Anatolia that reached Chalcedon,[18] across the Bosphorus from Constantinople.c[›][27][44] The Persian conquest was a gradual process; by the time of Heraclius' accession the Persians had conquered all Roman cities east of the Euphrates and in Armenia before moving on to Cappadocia, where their general Shahin took Caesarea.[40][41][44] There, Phocas' son-in-law Priscus, who had encouraged Heraclius and his father to rebel, started a year-long siege to trap them inside the city.[23][45][46]

Heraclius' accession as Emperor did little to reduce the Persian threat. Heraclius began his reign by attempting to make peace with the Persians, since Phocas, whose actions were the original casus belli, had been overthrown. The Persians rejected these overtures, however, since their armies were widely victorious.[39] According to historian Walter Kaegi, it is conceivable that the Persians' goal was to restore or even surpass the boundaries of the Achaemenid Empire by destroying the Byzantine empire, though because of the loss of Persian archives, no document survives to conclusively prove this.[39]

By established practice, Byzantine emperors did not personally lead troops into battle.d[›] Heraclius ignored this convention and joined with his general Priscus' siege of the Persians at Caesarea.[46] Priscus pretended to be ill, however, and did not meet the emperor. This was a veiled insult to Heraclius, who hid his dislike of Priscus and returned to Constantinople in 612. Meanwhile, Shahin's troops escaped Priscus' blockade and burned Caesarea, much to Heraclius' displeasure.[47] Priscus was soon removed from command, along with others who served under Phocas.[48] Philippicus, an old general of Maurice's, was appointed as commander-in-chief, but he proved himself incompetent against the Persians, avoiding engagements in battle.[49] Heraclius then appointed himself commander along with his brother Theodore to finally solidify command of the army.[49]

Khosrau took advantage of the incompetence of Heraclius' generals to launch an attack on Byzantine Syria, under the leadership of the Persian general Shahrbaraz.[50] Heraclius attempted to stop the invasion at Antioch, but despite the blessing of Saint Theodore of Sykeon,[49] Byzantine forces under Heraclius and Nicetas suffered a serious defeat at the hands of Shahin. Details of the battle are not known.[51] After this victory the Persians looted the city, slew the Patriarch of Antioch and deported many citizens. Roman forces lost again while attempting to defend the area just to the north of Antioch at the Cilician Gates, despite some initial success. The Persians then captured Tarsus and the Cilician plain.[52] This defeat cut the Byzantine empire in half, severing Constantinople and Anatolia's land link to Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and the Exarchate of Carthage.[52]

Persian dominance

Capture of Jerusalem

Resistance to the Persians in Syria was not strong; although the locals constructed fortifications, they generally tried to negotiate with the Persians.[52] The cities of Damascus, Apamea, and Emesa fell quickly in 613, giving the Sasanian army a chance to strike further south into Palaestina Prima. Nicetas continued to resist the Persians but was defeated at Adhri'at. He managed to win a small victory near Emesa, however, where both sides suffered heavy casualties—the total death count was 20,000.[53] More seriously, the weakness of the resistance enabled the Persians and their Jewish allies to capture Jerusalem following a three weeks siege.[54] Ancient sources claim 57,000 or 66,500 people were slain there; another 35,000 were deported to Persia, including the Patriarch Zacharias.[53]

Many churches in the city (including the Church of the Resurrection or Holy Sepulchre) were burned, and numerous relics, including the True Cross, the Holy Lance, and the Holy Sponge, were carried off to the Persian capital Ctesiphon. The loss of these relics was thought by many Christian Byzantines to be a clear mark of divine displeasure.[33] Some blamed the Jews for this misfortune and for the loss of Syria in general.[55] There were reports that Jews helped the Persians capture certain cities and that the Jews tried to slaughter Christians in cities that the Persians had already conquered but were found and foiled from doing so. These reports are likely to be greatly exaggerated and the result of general hysteria.[52]

Egypt

In 618 Shahrbaraz's forces invaded Egypt, a province that had been mostly untouched by war for three centuries.[56] The Monophysites living in Egypt were unhappy with Chalcedonian orthodoxy and were not eager to aid Byzantine imperial forces. Afterward they were supported by Khosrau,[56][57] but they did not resist imperial forces between 600 and 638, and many saw the Persian occupation in negative terms.[58][59] Byzantine resistance in Alexandria was led by Nicetas. After a year-long siege, resistance in Alexandria collapsed, supposedly after a traitor told the Persians of an unused canal, allowing them to storm the city. Nicetas fled to Cyprus along with Patriarch John the Almsgiver, who was a major supporter of Nicetas in Egypt.[60] The fate of Nicetas is unclear, since he disappears from records after this, but Heraclius was presumably deprived of a trusted commander.[61] The loss of Egypt was a severe blow to the Byzantine empire, as Constantinople relied on grain shipments from fertile Egypt to feed the multitudes in the capital. The free grain ration in Constantinople, which echoed the earlier grain dole in Rome, was abolished in 618.[62]

After conquering Egypt, Khosrau sent Heraclius the following letter:

Khosrau, greatest of Gods, and master of the earth, to Heraclius, his vile and insensate slave. Why do you still refuse to submit to our rule, and call yourself a king? Have I not destroyed the Greeks? You say that you trust in your God. Why has he not delivered out of my hand Caesarea, Jerusalem, and Alexandria? And shall I not also destroy Constantinople? But I will pardon your faults if you submit to me, and come hither with your wife and children; and I will give you lands, vineyards, and olive groves, and look upon you with a kindly aspect. Do not deceive yourself with vain hope in that Christ, who was not able to save himself from the Jews, who killed him by nailing him to a cross. Even if you take refuge in the depths of the sea, I will stretch out my hand and take you, whether you will or no.

Anatolia

When the Sasanians reached Chalcedon in 615, it was at this point, according to Sebeos, that Heraclius had agreed to stand down and was about ready to become a client of the Sasanian emperor Khosrow II, allowing the Roman Empire to become a Persian client state, as well as even allow Khosrow II to choose the emperor.[65][66] Things began to look even more grim for the Byzantines when Chalcedon fell in 617 to Shahin, making the Persians visible from Constantinople.[67] Shahin courteously received a peace delegation but claimed that he did not have the authority to engage in peace talks, directing Heraclius to Khosrau, who rejected the peace offer.[68][69] Still, the Persian forces soon withdrew, probably to focus on their invasion of Egypt.[70][71] Yet the Persians retained their advantage, capturing Ancyra, an important military base in central Anatolia, in 620 or 622. Rhodes and several other islands in the eastern Aegean fell in 622/3, threatening a naval assault on Constantinople.[72][73][74][75] Such was the despair in Constantinople that Heraclius considered moving the government to Carthage in Africa.[62]

Byzantine resurgence

Reorganization

Khosrau's letter did not cow Heraclius but prompted him to try a desperate strike against the Persians.[67] He now reorganized the remainder of his empire to allow his forces to fight on. Already, in 615, a new, lighter (6.82 grams) silver imperial coin appeared with the usual image of Heraclius and his son Heraclius Constantine, but uniquely carried the inscription of Deus adiuta Romanis or "May God help the Romans"; Kaegi believes this shows the desperation of the empire at this time.[76] The copper follis also dropped in weight from 11 grams to somewhere between 8 and 9 grams. Heraclius faced severely decreased revenues due to the loss of provinces; furthermore, a plague broke out in 619, which further damaged the tax base and also increased fears of divine retribution.[77] The debasement of the coinage allowed the Byzantines to maintain expenditure in the face of declining revenues.[76]

Heraclius now halved the pay of officials, enforced increased taxation, forced loans, and levied extreme fines on corrupt officials in order to finance his counter-offensive.[78] Despite disagreements over the incestuous marriage of Heraclius to his niece Martina, the clergy of the Byzantine Empire strongly backed his efforts against the Persians by proclaiming the duty of all Christian men to fight and by offering to give him a war loan consisting of all the gold and silver-plated objects in Constantinople. Precious metals and bronze were stripped from monuments and even the Hagia Sophia.[79] This military campaign has been seen as the first "crusade", or at least as an antecedent to the Crusades, by many historians, beginning with William of Tyre,[64][67][80][81] but some, like Kaegi, disagree with this moniker because religion was just one component in the war.[82] Thousands of volunteers were gathered and equipped with money from the church.[67] Heraclius himself decided to command the army from the front lines. Thus, the Byzantine troops had been replenished, re-equipped, and were now led by a competent general— while maintaining a full treasury.[67]

Historian George Ostrogorsky believed that volunteers were gathered through the reorganization of Anatolia into four themes, where the volunteers were given inalienable grants of land on the condition of hereditary military service.[83] However, modern scholars generally discredit this theory, placing the creation of the themes later, under Heraclius' successor Constans II.[84][85]

Byzantine counter-offensive

By 622, Heraclius was ready to mount a counter-offensive. He left Constantinople the day after celebrating Easter on Sunday, 4 April 622.[86] His young son, Heraclius Constantine, was left behind as regent under the charge of Patriarch Sergius and the patrician Bonus. He spent the summer training to improve the skills of his men and his own generalship. In the autumn, Heraclius threatened Persian communications from the Euphrates valley to Anatolia by marching to Cappadocia.[78] This forced the Persian forces in Anatolia under Shahrbaraz to retreat from the front-lines of Bithynia and Galatia to eastern Anatolia in order to block his access to Persia.[87]

What followed next is not entirely clear, but Heraclius certainly won a crushing victory over Shahrbaraz in the fall of 622.[88] The key factor was Heraclius' discovery of Persian forces hidden in ambush and responding by feigning retreat during the battle. The Persians left their cover to chase the Byzantines, whereupon Heraclius' elite Optimatoi assaulted the pursuing Persians, causing them to flee.[87] Thus he saved Anatolia from the Persians. Heraclius had to return to Constantinople, however, to deal with the threat posed to his Balkan domains by the Avars, so he left his army to winter in Pontus.[78][89]

Avar threat

While the Byzantines were occupied with the Persians, the Avars and Slavs poured into the Balkans, capturing several Byzantine cities, including Singidunum (Belgrade), Viminacium (Kostolac), Naissus (Niš), and Serdica (Sofia), while destroying Salona in 614. Isidore of Seville even claims that the Slavs took "Greece" from the Byzantines.[90] The Avars also began to raid Thrace, threatening commerce and agriculture, even near the gates of Constantinople.[90] However, numerous attempts by the Avars and Slavs to take Thessalonica, the most important Byzantine city in the Balkans after Constantinople, ended in failure, allowing the Empire to hold onto a vital stronghold in the region.[91] Other minor cities on the Adriatic coast like Jadar (Zadar), Tragurium (Trogir), Butua (Budva), Scodra (Skadar), and Lissus (Ljes) also survived the invasions.[92]

Because of the need to defend against these incursions, the Byzantines could not afford to use all their forces against the Persians. Heraclius sent an envoy to the Avar Khagan, saying that the Byzantines would pay a tribute in return for the Avars to withdraw north of the Danube.[67] The Khagan replied by asking for a meeting on 5 June 623, at Heraclea in Thrace, where the Avar army was located; Heraclius agreed to this meeting, coming with his royal court.[93] The Khagan, however, put horsemen en route to Heraclea to ambush and capture Heraclius, so they could hold him for ransom.[94]

Heraclius was fortunately warned in time and managed to escape, chased by the Avars all the way to Constantinople. However, many members of his court, as well as an alleged 70,000 Thracian peasants who came to see their Emperor, were captured and killed by the Khagan's men.[95] Despite this treachery, Heraclius was forced to give the Avars a subsidy of 200,000 solidi along with his illegitimate son John Athalarichos, his nephew Stephen, and the illegitimate son of the patrician Bonus as hostages in return for peace. This left him more able to focus his war effort completely on the Persians.[94][96]

Byzantine assault on Persia

Heraclius offered peace to Khosrau, presumably in 624, threatening otherwise to invade Persia, but Khosrau rejected the offer.[97] On March 25, 624, Heraclius left Constantinople to attack the Persian heartland. He willingly abandoned any attempt to secure his rear or his communications with the sea,[97] marching through Armenia and modern Azerbaijan to assault the core Persian lands directly.[78] According to Walter Kaegi, Heraclius led an army of no more than 40,000, and most likely between 20,000–24,000.[98] Before journeying to the Caucasus, he recovered Caesarea, in defiance of the earlier letter that Khosrau had sent him.[98]

Heraclius advanced along the Araxes River, destroying Persian-held Dvin, the capital of Armenia, and Nakhchivan. At Ganzaka, Heraclius met Khosrau's army, some 40,000 strong. Using loyal Arabs, he captured and killed some of Khosrau's guards, leading to the disintegration of the Persian army. Heraclius then destroyed the famous fire temple of Takht-i-Suleiman, an important Zoroastrian shrine.e[›][99] Heraclius' raids went as far as the Gayshawan, a residence of Khosrau in Adurbadagan.[99]

Heraclius wintered in Caucasian Albania, gathering forces for the next year.[100] Khosrau was not content to let Heraclius quietly rest in Albania. He sent three armies, commanded by Shahrbaraz, Shahin, and Shahraplakan, to try to trap and destroy Heraclius' forces.[101] Shahraplakan retook lands up as far as Siwnik, aiming to capture the mountain passes. Shahrbaraz was sent to block Heraclius' retreat through Caucasian Iberia, and Shahin was sent to block the Bitlis Pass. Heraclius, planning to engage the Persian armies separately, spoke to his worried Lazic, Abasgian, and Iberian allies and soldiers, saying: "Do not let the number of our enemies disturb us. For, God willing, one will pursue ten thousand."[101]

Two soldiers who feigned desertion were sent to Shahrbaraz, claiming that the Byzantines were fleeing before Shahin. Due to jealousy between the Persian commanders, Shahrbaraz hurried with his army to take part in the glory of the victory. Heraclius met them at Tigranakert and routed the forces of Shahraplakan and Shahin one after the other. Shahin lost his baggage train, and Shahraplakan (according to one source) was killed, though he re-appears later.[101][102][103] After this victory, Heraclius crossed the Araxes and camped in the plains on the other side. Shahin, with the remnants of both his and Shahraplakan's armies joined Shahrbaraz in the pursuit of Heraclius, but marshes slowed them down.[102][103] At Aliovit, Shahrbaraz split his forces, sending some 6,000 troops to ambush Heraclius while the remainder of the troops stayed at Aliovit. Heraclius instead launched a surprise night attack on the Persian main camp in February 625, destroying it. Shahrbaraz only barely escaped, naked and alone, having lost his harem, baggage, and men.[102]

Heraclius spent the rest of winter to the north of Lake Van.[102] In 625, his forces attempted to push back towards the Euphrates. In a mere seven days, he bypassed Mount Ararat and the 200 miles along the Arsanias River to capture Amida and Martyropolis, important fortresses on the upper Tigris.[78][104][105] Heraclius then carried on towards the Euphrates, pursued by Shahrbaraz. According to Arab sources, he was stopped at the Satidama or Batman Su River and defeated; Byzantine sources, however, do not mention this incident.[105] There was then another minor skirmish between Heraclius and Shahrbaraz at the Sarus river near Adana.[106] Shahrbaraz stationed his forces across the river from the Byzantines.[78] A bridge spanned the river, and the Byzantines immediately charged across. Shahrbaraz feigned retreat to lead the Byzantines into an ambush, and the vanguard of Heraclius' army was destroyed within minutes. The Persians, however, had neglected to cover the bridge, and Heraclius charged across with the rearguard, unafraid of the arrows that the Persians fired, turning the tide of battle against the Persians.[107] Shahrbaraz expressed his admiration at Heraclius to a renegade Greek: "See your Emperor! He fears these arrows and spears no more than would an anvil!"[107] The Battle of Sarus was a successful retreat for the Byzantines that panegyrists magnified.[106] In the aftermath of the battle, the Byzantine army wintered at Trebizond.[107]

Climax of the war

Siege of Constantinople

Khosrau, seeing that a decisive counterattack was needed to defeat the Byzantines, recruited two new armies from all the able men, including foreigners.[107] Shahin was entrusted with 50,000 men and stayed in Mesopotamia and Armenia to prevent Heraclius from invading Persia; a smaller army under Shahrbaraz slipped through Heraclius' flanks and bee-lined for Chalcedon, the Persian base across the Bosphorus from Constantinople. Khosrau also coordinated with the Khagan of the Avars so as to launch a coordinated attack on Constantinople from both European and Asiatic sides.[104] The Persian army stationed themselves at Chalcedon, while the Avars placed themselves on the European side of Constantinople and destroyed the Aqueduct of Valens.[108] Because of the Byzantine navy's control of the Bosphorus strait, however, the Persians could not send troops to the European side to aid their ally.[109][110] This reduced the effectiveness of the siege, because the Persians were experts in siege warfare.[111] Furthermore, the Persians and Avars had difficulties communicating across the guarded Bosphorus—though undoubtedly, there was some communication between the two forces.[104][110][112]

The defense of Constantinople was under the command of Patriarch Sergius and the patrician Bonus.[113] Upon hearing the news, Heraclius split his army into three parts; although he judged that the capital was relatively safe, he still sent some reinforcements to Constantinople to boost the morale of the defenders.[113] Another part of the army was under the command of his brother Theodore and was sent to deal with Shahin, while the third and smallest part would remain under his own control, intending to raid the Persian heartland.[107]

On 29 June 626, a coordinated assault on the walls began. Inside the walls, some 12,000 well-trained Byzantine cavalry troops (presumably dismounted) defended the city against the forces of some 80,000 Avars and Slavs.[107] Despite continuous bombardment for a month, morale was high inside the walls of Constantinople because of Patriarch Sergius' religious fervor and his processions along the wall with the icon of the Virgin Mary, inspiring the belief that the Byzantines were under divine protection.[114][115]

On 7 August, a fleet of Persian rafts ferrying troops across the Bosphorus were surrounded and destroyed by Byzantine ships. The Slavs under the Avars attempted to attack the sea walls from across the Golden Horn, while the main Avar host attacked the land walls. Patrician Bonus' galleys rammed and destroyed the Slavic boats; the Avar land assault from August 6 to the 7th also failed.[116] With the news that Theodore had decisively triumphed over Shahin (supposedly leading Shahin to die from depression), the Avars retreated to the Balkan hinterland within two days, never to seriously threaten Constantinople again. Even though the army of Shahrbaraz was still encamped at Chalcedon, the threat to Constantinople was over.[113][114] In thanks for the lifting of the siege and the supposed divine protection of the Virgin Mary, the celebrated Akathist Hymn was written by an unknown author, possibly Patriarch Sergius or George of Pisidia.[117][118][119]

Furthermore, after the emperor showed Shahrbaraz intercepted letters from Khosrau ordering the Persian general's death, the latter switched to Heraclius' side.[120] Shahrbaraz then moved his army to northern Syria, where he could easily decide to support either Khosrau or Heraclius at a moment's notice. Still, with the neutralization of Khosrau's most skilled general, Heraclius deprived his enemy of some of his best and most experienced troops, while securing his flanks prior to his invasion of Persia.[121]

Byzantine-Turkic alliance

During the siege of Constantinople, Heraclius formed an alliance with people Byzantine sources called the "Khazars," under Ziebel, now generally identified as the Western Turkic Khaganate of the Göktürks, led by Tong Yabghu,[122] plying him with wondrous gifts and the promise of marriage to the porphyrogenita Eudoxia Epiphania. Earlier, in 568, the Turks under Istämi had turned to Byzantium when their relations with Persia soured over commerce issues.[123] Istämi sent an embassy led by the Sogdian diplomat Maniah directly to Constantinople, which arrived in 568 and offered not only silk as a gift to Justin II, but also proposed an alliance against Sassanid Persia. Justin II agreed and sent an embassy to the Turkic Khaganate, ensuring the direct Chinese silk trade desired by the Sogdians.[124][125]

The Turks, based in the Caucasus, responded by sending 40,000 of their men to ravage the Persian empire in 626, marking the start of the Third Perso-Turkic War.[107] Joint Byzantine and Göktürk operations were then focused on besieging Tiflis, where the Byzantines used traction trebuchets to breach the walls, one of the first known uses by the Byzantines.f[›][126] Khosrau sent 1,000 cavalry under Shahraplakan to reinforce the city,[127] but it nevertheless fell, probably in late 628.[128] Ziebel died by the end of that year, however, saving Epiphania from marriage to a barbarian.[107] Whilst the siege proceeded, Heraclius worked to secure his base in the upper Tigris.[113]

Battle of Nineveh

In mid-September 627, Heraclius invaded the Persian heartland in a surprising winter campaign, leaving Ziebel to continue the siege of Tiflis. Edward Luttwak describes the seasonal retreat of Heraclius for the winters of 624–626 followed by a change in 627 to threaten Ctesiphon as a "high-risk, relational maneuver on a theater-wide scale" because it habituated the Persians to strategically ineffective raids that caused them to decide not to recall border troops to defend the heartland.[129] His army numbered between 25,000 and 50,000 Byzantine troops and 40,000 Göktürks that quickly deserted him because of the unfamiliar winter conditions and harassment from the Persians.[130][131] He advanced quickly but was tailed by a Persian army under the Armenian Rhahzadh, who faced difficulties in provisioning his army due to the Byzantines taking most of the provisions as they moved south toward Assyria.[131][132][133]

Towards the end of the year, near the ruins of Nineveh, Heraclius engaged Rhahzadh before reinforcements could reach the Persian commander.[134] The Battle of Nineveh took place in the fog, reducing the Persian advantage in missile troops. Heraclius feigned retreat, leading the Persians to the plains, before reversing his troops to the surprise of the Persians.[135] After eight hours of fighting, the Persians suddenly retreated to nearby foothills, but the battle did not become a rout.[114][136] During the battle, approximately 6,000 Persians were killed.[137] Patriarch Nikephoros' Brief History suggests that Rhahzadh challenged Heraclius to personal combat, and that Heraclius accepted and killed Rhahzadh in a single thrust; two other challengers fought against him and also lost.[114][138] However, he received an injury to his lip.[139]

End of the war

With no Persian army left to oppose him, Heraclius' victorious army plundered Dastagird, which was a palace of Khosrau's, and gained tremendous riches while recovering 300 captured Byzantine flags.[140] Khosrau had already fled to the mountains of Susiana to try to rally support for the defense of Ctesiphon.[113][114] Heraclius then issued an ultimatum to Khosrau:

I pursue and run after peace. I do not willingly burn Persia, but compelled by you. Let us now throw down our arms and embrace peace. Let us quench the fire before it burns up everything.— Heraclius' ultimatum to Khosrau II, 6 January 628[141]

However, Heraclius could not attack Ctesiphon itself, as the Nahrawan Canal was blocked due to the collapse of a bridge leading over it,[140] and he did not attempt to bypass the canal.[142]

Regardless, the Persian army rebelled and overthrew Khosrau II, raising his son Kavadh II, also known as Siroes, in his stead. Khosrau was shut in a dungeon, where he suffered for five days on bare sustenance—he was shot to death slowly with arrows on the fifth day.[143] Kavadh immediately sent peace offers to Heraclius. Heraclius did not impose harsh terms, knowing that his own empire was also near exhaustion. Under the terms of the peace treaty, the Byzantines regained all their lost territories, their captured soldiers, a war indemnity, and most importantly for them, the True Cross and other relics that were lost in Jerusalem in 614.[143][144][145]

Significance

Short-term consequences

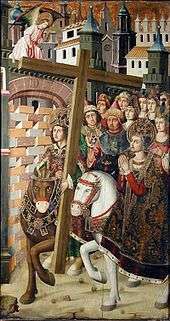

After some months of travel, Heraclius entered Constantinople in triumph and was met by the people of the city, his son Heraclius Constantine, and Patriarch Sergius, prostrating themselves in joy.[146] His alliance with the Persians resulted in the recovery of the Holy Sponge which fastened to the True Cross in an elaborate ceremony on 14 September 629.[147] The ceremonial parade went toward the Hagia Sophia. There, the True Cross was slowly raised up until it vertically towered over the high altar. To many, this was a sign that a new golden age was about to begin for the Byzantine Empire.[143][148]

The victorious conclusion of the war cemented Heraclius' position as one of history's most successful generals. He was hailed as "the new Scipio" for his six years of unbroken victories and for leading the Roman army where no Roman army had ever gone before.[64][144] The triumphal raising of the True Cross in the Hagia Sophia was a crowning moment in his achievements. Had Heraclius died then, he would have been recorded in history, in the words of the historian Norman Davies, as "the greatest Roman general since Julius Caesar".[64] Instead, he lived through the Arab invasions, losing battle after battle against their onslaught and tarnishing his reputation for victory. John Norwich succinctly described Heraclius as having "lived too long".[149]

For their part, the Sassanids struggled to establish a stable government. When Kavadh II died only months after coming to the throne, Persia was plunged into several years of dynastic turmoil and civil war. Ardashir III, Heraclius' ally Shahrbaraz, and Khosrau's daughters Purandokht and Azarmidokht all succeeded to the throne within months of each other. Only when Yazdgerd III, a grandson of Khosrau II, succeeded to the throne in 632 was there stability, but by then it was too late to rescue the Sassanid kingdom.[150][151]

Long-term consequences

The devastating impact of the war of 602–628, along with the cumulative effects of a century of almost continuous Byzantine-Persian conflict, left both empires crippled. The Sassanids were further weakened by economic decline, heavy taxation to finance Khosrau II's campaigns, religious unrest, and the increasing power of the provincial landholders at the expense of the Shah.[152] According to Howard-Johnston: "[Heraclius'] victories in the field over the following years and their political repercussions ... saved the main bastion of Christianity in the Near East and gravely weakened its old Zoroastrian rival. They may be shadowed by the even more extraordinary military achievements of the Arabs in the following two decades, but hindsight should not be allowed to dim their lustre."[153]

However, the Byzantine Empire was also severely affected, with the Balkans now largely in the hands of the Slavs.[154] Additionally, Anatolia had been devastated by repeated Persian invasions, and the empire's hold on its recently regained territories in the Caucasus, Syria, Mesopotamia, Palestine, and Egypt was loosened by years of Persian occupation.g[›][155] With their financial reserves exhausted, the Byzantines found difficulties paying veterans of the war with the Persians and recruiting new troops.[154][156][157] Clive Foss called this war the "first stage in the process which marked the end of Antiquity in Asia Minor."[158]

Neither empire was given much chance to recover, as within a few years they were struck by the onslaught of the Arabs, newly united by Islam,[159] which Howard-Johnston likened to "a human tsunami".[160] According to George Liska, the "unnecessarily prolonged Byzantine–Persian conflict opened the way for Islam".[161] The Sassanid Empire rapidly succumbed to these attacks and was completely destroyed. During the Byzantine–Arab Wars, the exhausted Byzantine Empire's recently regained eastern and southern provinces of Syria, Armenia, Egypt, and North Africa were also lost, reducing the empire to a territorial rump consisting of Anatolia and a scatter of islands and footholds in the Balkans and Italy.[155] However, unlike Persia, the Byzantine Empire ultimately survived the Arab assault, holding onto its residual territories and decisively repulsing two Arab sieges of its capital in 674–678 and 717–718.[153][162] The Byzantine Empire also lost its territories in Crete and southern Italy to the Arabs in later conflicts, though these too were ultimately recovered.[163][164] However Balearic Islands, Sardinia and Sicily were captured by Arabs and Corsica by Lombards by 8th century. Also, Visigoths captured Spania, Byzantine holdings in Spain by 629.

Composition of the armies and strategy

The elite cavalry corps of the Persians was the Savārān cavalry.[165] The lance was probably their preferred weapon, having the power to skewer two men simultaneously.[166] Their horses were covered in lamellar armor to protect them from enemy archers.[167] Persian archers had a lethal range of about 175 meters and accurate range at about 50–60 meters.[168]

According to Emperor Maurice's Strategikon, a manual of war, the Persians made heavy use of archers that were the most "rapid, although not powerful archery" of all warlike nations, and they avoided weather that hampered their bows.[111] It claims that they deployed so that their formation was equal in strength in the center and the flanks. They also apparently avoided the charge of Roman lancers by using rough terrain since they tended to avoid hand-to-hand combat. Thus, the Strategikon advised fighting on level terrain with rapid charges to avoid the Persian arrows. They were seen as skilled in laying siege and liked to "achieve their results by planning and generalship."[111]

The most important arm of the Byzantine army was its cataphract cavalry, which became a symbol of Byzantium.[169] They wore chain mail, had heavily armored horses, and used lances as their primary weapon. They had small shields mounted on their arms, could also use bows, and carried a broadsword and an axe.[170] Heavy Byzantine infantry, or scutati, carried small round shields and wore lamellar armor. They carried many weapons against enemy cavalry such as spears to ward off cavalry and axes to cut the legs off of horses.[171] Light Byzantine infantry, or psiloi, primarily used bows and wore only leather armor.[172] Byzantine infantry played a key role in stabilizing battle lines against enemy cavalry and also as an anchor to launch friendly cavalry attacks. According to Richard A. Gabriel, the Byzantine heavy infantry "combined the best capabilities of the Roman legion with the old Greek phalanx."[173]

The Avars had mounted archers with composite bows that could double as heavy cavalry with lances. They were skilled in siegecraft and could construct trebuchets and siege towers. In their siege of Constantinople, they constructed walls of circumvallation to prevent easy counterattack and used mantelets or wooden frames covered with animal hides to protect against defending archers. Furthermore, like many nomads, they gathered other warriors such as Gepids and Slavs to assist them.[174] However, since Avars depended on raiding the countryside for supplies, it was difficult for them to maintain long sieges, especially when considering their less mobile gathered allies.[175]

According to Kaegi, the Byzantines had "an almost compulsive ... preference to avoid changing the essential elements of the status quo."[176] They tried with all diplomatic means to secure allies and divide their enemies. Although they failed against Khosrau and the Avar Khagan, their ties with the Slavs who would become the Serbs and Croats and their decades-long negotiations with the Göktürks resulted in Slavs actively opposing the Avars in addition to a key alliance with the Göktürks.[177]

As for any army, logistics were always a problem. In his initial campaigns in Byzantine territories, especially in Anatolia, Heraclius likely supplied his troops by requisitioning from his surroundings.[178] During Heraclius' offensive raids into Persia, each time the harsh conditions of winter forced him to desist, partly because both his and the Persian horses needed stored fodder in winter quarters. Forcing his troops to campaign in the winter would be risky as Maurice had been overthrown due to his poor treatment of his troops in winter.[179] Edward Luttwak believes that the Göktürks with their "hardy horses (or ponies)" that could survive "in almost any terrain that had almost any vegetation" were essential in Heraclius' winter campaign in hilly northeast Iran in 627.[180] During the campaign, they took the provisions from Persian lands.[132][133] With the victory at Nineveh and the capture of Persian palaces, they no longer had issues with supplying their troops in foreign territories and with winter conditions.[181]

Historiography

The sources for this war are mostly of Byzantine origin. Foremost among the contemporary Greek texts is the Chronicon Paschale by an unidentified author from around 630.[182][183] George of Pisidia wrote many poems and other works that were contemporary. Theophylact Simocatta has surviving letters along with a history that gives the political outlook of the Byzantines, but that history only really covers from 582 to 602.[182][183][184] Theodore the Synkellos has a surviving speech, which was made during the Siege of Constantinople in 626, that contains useful information for some events. There are some surviving papyri from Egypt from that period.[182]

The Persian archives were lost so there are no contemporary Persian sources of this war.[39] However, al-Tabari's History of the Prophets and Kings uses now lost sources and contains a history of the Sassanid dynasty.[184] Non-Greek contemporary sources include the Chronicle of John of Nikiu, which was written in Coptic but only survives in Ethiopian translation, and the History attributed to Sebeos (there is controversy over the authorship). The latter is an Armenian compilation of various sources, arranged in only rough chronological order. This gives it an uneven coverage of the war. Furthermore, it was put together with the purpose of correlating Biblical prophecy and contemporary times, making it most certainly not objective.[185] There are also some surviving Syriac materials from that period, which Dodgeon, Greatrex, and Lieu believe are the "most important" of the contemporary sources.[183][185] These include the Chronicle of 724 by Thomas the Presbyter, composed in 640. The Chronicle of Guidi or Khuzistan Chronicle gives the perspective of a Nestorian Christian living in Persian territory.[183]

Later Greek accounts include Chronicle of Theophanes the Confessor and the Brief History of Patriarch Nikephoros I. Theophanes' Chronicle is very useful in creating a framework of the war.[186] It is usually supplemented by even later Syriac sources like the Chronicle of 1234 and the Chronicle by Michael the Syrian.[183] However, these sources, excepting the Brief History by Nikephoros, and the Christian Arab Agapius of Hierapolis all likely drew their information from a common source, probably the 8th-century historian Theophilos of Edessa.[183][186]

The 10th-century Armenian History of the House of Artsrunik by Thomas Artsruni probably have similar sources to the ones that the compiler of Sebeos used. Movses Kaghankatvatsi wrote the History of Armenia in the 10th century and has material from unidentified sources on the 620s.[187] Howard-Johnston considered the histories of Movses and Sebeos as "the most important of extant non-Muslim sources".[188] The history of the Patriarch Eutychius of Alexandria contains many errors, but is a useful source. The Quran also provides some detail, but can only be used cautiously.[186]

The Byzantine hagiographies (lives of saints), of Saints Theodore of Sykeon and Anastasios the Persian have proven to be helpful in understanding the era of the war.[186] The Life of George of Khozeba gives an idea of the panic at the time of the Siege of Jerusalem.[189] However, there are some doubts as to whether hagiographic texts may be corrupted from 8th or 9th century interpolations.[190] Numismatics, or the study of coins, has proven useful to dating.[191] Sigillography, or the study of seals, is also used for dating. Art and other archaeological findings are also of some use. Epigraphic sources or inscriptions are of limited use.[190] Luttwak called the Strategikon of Maurice the "most complete Byzantine field manual";[192] it provides valuable insight into the military thinking and practices of the time.[193]

Notes and Citations

Notes

^ a: All dates, especially between 602–620 are only approximate. This is primarily because many popular sources like Theophanes' Chronicles are all drawn from a common source, thought to be a history by Theophilus of Edessa. Thus, there are few independent witnesses of the following events, making reliable dating difficult.[183]

^ b: The war had originally begun when Justin II had refused to give the Sassanids the usual tribute dating from the time of Justinian I. The successful conclusion to that war meant that the tribute was no longer paid.[194]

^ c: Some authors, including Dodgeon, Greatrex, and Lieu, have expressed the belief that the raid on Chalcedon is fictitious.[41] Either way, by 610, the Persians captured all the Byzantine cities east of the Euphrates.

^ d: Since the time of Theodosius I, no Roman emperor had personally led troops in battle. Heraclius was the first soldier-emperor since then.[47]

^ e: Thebarmes, described in Theophanes' Chronicles, is usually identified with Takht-i-Suleiman.[195]

^ f: That was the first known usage of the term helepolis to describe the trebuchet, though earlier uses may be attested to in Emperor Maurice's Strategikon.[196]

^ g: Ambivalence toward Byzantine rule on the part of monophysites may have lessened local resistance to the Arab expansion.[155]

References

- ↑ Pourshariati (2008), p. 142

- 1 2 Norwich 1997, p. 87

- ↑ Oman 1893, p. 151

- ↑ Dodgeon, Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 174

- ↑ Dodgeon, Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 175

- ↑ Oman 1893, p. 152

- ↑ Norwich 1997, p. 86

- ↑ Oman 1893, p. 149

- ↑ Treadgold 1998, p. 205

- ↑ Treadgold 1998, pp. 205–206

- ↑ Luttwak 2009, p. 401

- 1 2 3 Treadgold 1997, p. 235

- ↑ Oman 1893, p. 153

- ↑ Oman 1893, p. 154

- ↑ Ostrogorsky 1969, p. 83

- ↑ Norwich 1997, p. 88

- ↑ Dodgeon, Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 183–84

- 1 2 Oman 1893, p. 155

- ↑ Foss 1975, p. 722

- 1 2 Dodgeon, Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 184

- ↑ Norwich 1997, p. 89

- 1 2 3 Kaegi 2003, p. 39

- 1 2 Kaegi 2003, p. 37

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 41

- 1 2 3 Dodgeon, Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 187

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 55

- 1 2 Oman 1893, p. 156

- 1 2 Kaegi 2003, p. 53

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 87

- ↑ Dodgeon, Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 194

- ↑ Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, p. 942

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 49

- 1 2 Norwich 1997, p. 90

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 52

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 54

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 60

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 63

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 64

- 1 2 3 4 Kaegi 2003, p. 65

- 1 2 3 Kaegi 2003, p. 67

- 1 2 3 4 Dodgeon, Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 186

- ↑ Brown, Churchill & Jeffrey 2002, p. 176

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, pp. 67–68

- 1 2 Dodgeon, Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 185

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 68

- 1 2 Dodgeon, Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 188

- 1 2 Kaegi 2003, p. 69

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 71

- 1 2 3 Kaegi 2003, p. 75

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 74

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, pp. 76–77

- 1 2 3 4 Kaegi 2003, p. 77

- 1 2 Kaegi 2003, p. 78

- ↑ Ostrogorsky 1969, p. 95

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 80

- 1 2 Oman 1893, p. 206

- ↑ Fouracre 2006, p. 296

- ↑ Kaegi 1995, p. 30

- ↑ Reinink, Stolte & Groningen 2002, p. 235

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 91

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 92

- 1 2 Kaegi 2003, p. 88

- ↑ Oman 1893, pp. 206–207

- 1 2 3 4 Davies 1998, p. 245

- ↑ Pourshariati 2008, p. 141.

- ↑ Pourshariati 2010, p. 1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Oman 1893, p. 207

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 84

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 85

- ↑ Foss 1975, p. 724

- ↑ Luttwak 2009, p. 398

- ↑ Kia 2016, p. 223.

- ↑ Greatrex & Lieu 2005, p. 197.

- ↑ Howard-Johnston 2006, p. 33.

- ↑ Foss 1975, p. 725

- 1 2 Kaegi 2003, p. 90

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 105

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Norwich 1997, p. 91

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 110

- ↑ Chrysostomides, Dendrinos & Herrin 2003, p. 219

- ↑ Runciman 2005, p. 5

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 126

- ↑ Ostrogorsky 1969, pp. 95–98;101

- ↑ Treadgold 1997, p. 316

- ↑ Haldon 1997, pp. 211–217

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 112

- 1 2 Kaegi 2003, p. 115

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 114

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 116

- 1 2 Kaegi 2003, p. 95

- ↑ Ostrogorsky 1969, p. 93

- ↑ Ostrogorsky 1969, p. 94

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 118

- 1 2 Oman 1893, p. 208

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 119

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 120

- 1 2 Kaegi 2003, p. 122

- 1 2 Kaegi 2003, p. 125

- 1 2 Kaegi 2003, p. 127

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 128

- 1 2 3 Kaegi 2003, p. 129

- 1 2 3 4 Kaegi 2003, p. 130

- 1 2 Dodgeon, Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 204

- 1 2 3 Oman 1893, p. 210

- 1 2 Kaegi 2003, p. 131

- 1 2 Kaegi 2003, p. 132

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Norwich 1997, p. 92

- ↑ Treadgold 1997, p. 297

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 133

- 1 2 Kaegi 2003, p. 140

- 1 2 3 Dodgeon, Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 179–81

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 134

- 1 2 3 4 5 Oman 1893, p. 211

- 1 2 3 4 5 Norwich 1997, p. 93

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 136

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 137

- ↑ Kimball 2010, p. 176

- ↑ Ekonomou 2008, p. 285

- ↑ Gambero 1999, p. 338

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 148

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 151

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 143

- ↑ Khanam 2005, p. 782

- ↑ Liu, Xinru, "The Silk Road: Overland Trade and Cultural Interactions in Eurasia", in Agricultural and Pastoral Societies in Ancient and Classical History, ed. Michael Adas, American Historical Association, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001, p. 168.

- ↑ Howard, Michael C., Transnationalism in Ancient and Medieval Societies: the Role of Cross Border Trade and Travel, McFarland & Company, 2012, p. 133.

- ↑ Dennis 1998, p. 104

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 144

- ↑ Dodgeon, Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 212

- ↑ Luttwak 2009, pp. 408

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, pp. 158–159

- 1 2 Dodgeon, Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 213

- 1 2 Kaegi 2003, p. 159

- 1 2 Dodgeon, Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 215

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 160

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 161

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 163

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 169

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 167

- ↑ Farrokh 2007, p. 259

- 1 2 Kaegi 2003, p. 173

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 172

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 174

- 1 2 3 Norwich 1997, p. 94

- 1 2 Oman 1893, p. 212

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, pp. 178, 189–190

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, pp. 185–86

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 189

- ↑ Bury 2008, p. 245

- ↑ Norwich 1997, p. 97

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 227

- ↑ Beckwith 2009, p. 121

- ↑ Howard-Johnston 2006, p. 291

- 1 2 Howard-Johnston 2006, p. 9

- 1 2 Haldon 1997, pp. 43–45, 66, 71, 114–115

- 1 2 3 Haldon 1997, pp. 49–50

- ↑ Kaegi 1995, p. 39

- ↑ Kaegi 1995, pp. 43–44

- ↑ Foss 1975, p. 747

- ↑ Foss 1975, pp. 746–47

- ↑ Howard-Johnston 2006, p. xv

- ↑ Liska 1998, p. 170

- ↑ Haldon 1997, pp. 61–62

- ↑ Norwich 1997, p. 134

- ↑ Norwich 1997, p. 155

- ↑ Farrokh 2005, p. 5

- ↑ Farrokh 2005, p. 13

- ↑ Farrokh 2005, p. 18

- ↑ Farrokh 2005, p. 14

- ↑ Gabriel 2002, p. 281

- ↑ Gabriel 2002, p. 282

- ↑ Gabriel 2002, pp. 282–83

- ↑ Gabriel 2002, p. 283

- ↑ Gabriel 2002, p. 288

- ↑ Luttwak 2009, pp. 395–96

- ↑ Luttwak 2009, pp. 403

- ↑ Kaegi 1995, p. 32

- ↑ Luttwak 2009, p. 404

- ↑ Luttwak 2009, pp. 400

- ↑ Luttwak 2009, pp. 400–01

- ↑ Luttwak 2009, pp. 403–04

- ↑ Luttwak 2009, pp. 405–406

- 1 2 3 Kaegi 2003, p. 7

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Dodgeon, Greatrex & Lieu 2002, pp. 182–83

- 1 2 Dodgeon, Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. xxvi

- 1 2 Kaegi 2003, p. 8

- 1 2 3 4 Kaegi 2003, p. 9

- ↑ Dodgeon, Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. xxv

- ↑ Howard-Johnston 2006, pp. 42–43

- ↑ Dodgeon, Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 192

- 1 2 Kaegi 2003, p. 10

- ↑ Foss 1975, pp. 729–30

- ↑ Luttwak 2009, pp. 268–71

- ↑ Kaegi 2003, p. 14

- ↑ Ostrogorsky 1969, pp. 79–80

- ↑ Dodgeon, Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 200

- ↑ Dennis 1998, pp. 99–104

Bibliography

- Beckwith, Christopher (2009), Empires of the Silk Road: a history of Central Eurasia from the Bronze Age to the present, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-13589-4.

- Bury, J.B. (2008), History of the Later Roman Empire from Arcadius to Irene, Volume 2, Cosimo, Inc., ISBN 1-60520-405-6.

- Brown, Phyllis Rugg; Churchill, Laurie J.; Jeffrey, Jane E. (2002), Women Writing Latin: Women writing in Latin in Roman antiquity, late antiquity, and early modern Christian era, Taylor & Francis US, ISBN 0-415-94183-0.

- Chrysostomides, J.; Dendrinos, Charalambos; Herrin, Judith (2003), Porphyrogenita, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 0-7546-3696-8.

- Davies, Norman (1998), Europe: a history, HarperCollins, ISBN 0-06-097468-0.

- Dennis, George T. (1998), "Byzantine Heavy Artillery: the Helepolis" (PDF), Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies, Duke University, 39: 99–115, archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-08-05.

- Dodgeon, Michael H.; Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2002), The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363-630 AD), Routledge, ISBN 0-415-00342-3.

- Ekonomou, Andrew J. (2008), Byzantine Rome and the Greek Popes: Eastern Influences on Rome and the Papacy from Gregory the Great to Zacharias, A.d. 590-752, Parts 590-752, Lexington Books, ISBN 0-7391-1978-8.

- Farrokh, Kaveh (2005), Sassanian elite cavalry AD 224-642, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84176-713-1.

- Farrokh, Kaveh (2007), Shadows in the desert: ancient Persia at war, Osprey Publishing, ISBN 1-84603-108-7.

- Foss, Clive (1975), "The Persians in Asia Minor and the End of Antiquity", The English Historical Review, Oxford University Press, 90: 721–47, doi:10.1093/ehr/XC.CCCLVII.721.

- Fouracre, Paul (2006), The New Cambridge Medieval History: c. 500-c. 700, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-36291-1.

- Gabriel, Richard (2002), The great armies of antiquity, Greenwood Publishing Group, ISBN 0-275-97809-5.

- Gambero, Luigi (1999), Mary and the fathers of the church: the Blessed Virgin Mary in patristic thought, Ignatius Press, ISBN 0-89870-686-6.

- Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2005). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars AD 363-628. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134756469.

- Haldon, John (1997) [1990], Byzantium in the Seventh Century: the Transformation of a Culture, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-31917-X.

- Howard-Johnston, James (2006), East Rome, Sasanian Persia And the End of Antiquity: Historiographical And Historical Studies, Ashgate Publishing, ISBN 0-86078-992-6.

- Kaegi, Walter Emil (1995) [1992], Byzantium and the early Islamic conquests, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-48455-3.

- Kaegi, Walter Emil (2003), Heraclius: Emperor of Byzantium, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-81459-6.

- Kia, Mehrdad (2016). he Persian Empire: A Historical Encyclopedia [2 volumes]: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1610693912.

- Kimball, Virginia M. (2010), Liturgical Illuminations: Discovering Received Tradition in the Eastern Orthros of Feasts of the Theotokos, AuthorHouse, ISBN 1-4490-7212-7.

- Liska, George (1998), "Projection contra Prediction: Alternative Futures and Options", Expanding Realism: The Historical Dimension of World Politics, Rowman & Littlefield, ISBN 0-8476-8680-9.

- Luttwak, Edward (2009), The grand strategy of the Byzantine Empire, Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-03519-4.

- Martindale, John R.; Jones, A.H.M.; Morris, John (1992), The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire - Volume III, AD 527–641, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-20160-8.

- Norwich, John Julius (1997), A Short History of Byzantium, Vintage Books, ISBN 0-679-77269-3.

- Oman, Charles (1893), Europe, 476-918, Volume 1, Macmillan.

- Ostrogorsky, George (1969), History of the Byzantine State, Rutgers University Press, ISBN 978-0-8135-1198-6.

- Pourshariati, Parvaneh (2008). Decline and fall of the Sasanian empire: the Sasanian-Parthian confederacy and the Arab conquest of Iran. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1845116453.

- Pourshariati, Parvaneh (2010). The Sasanian Era. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0857711991.

- Reinink, Bernard H.; Stolte, Geoffrey; Groningen, Rijksuniversiteit te (2002), The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363-630 AD), Peeters Publishers, ISBN 90-429-1228-6.

- Runciman, Steven (2005), The First Crusade, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-61148-2.

- Treadgold, Warren T. (1997), A History of the Byzantine State and Society, Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-2630-2.

- Treadgold, Warren T. (1998), Byzantium and Its Army, 284-1081, Stanford University Press, ISBN 0-8047-3163-2.