Mardin

| Mardin | |

|---|---|

| Metropolitan Municipality | |

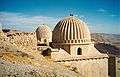

|

The old city of Mardin | |

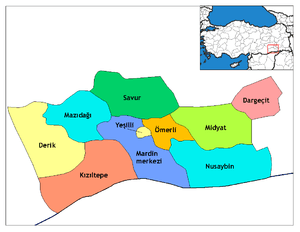

Mardin Location of Mardin within Turkey. | |

| Coordinates: 37°19′0″N 40°44′16″E / 37.31667°N 40.73778°ECoordinates: 37°19′0″N 40°44′16″E / 37.31667°N 40.73778°E | |

| Country |

|

| Region | Southeastern Anatolia |

| Province | Mardin |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Ahmet Türkl |

| • Co-Mayor | Februniye Akyol[1] |

| Area[2] | |

| • District | 969.06 km2 (374.16 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,083 m (3,553 ft) |

| Population (2012)[3] | |

| • Urban | 86,948 |

| • District | 139,254 |

| • District density | 140/km2 (370/sq mi) |

| Time zone | EET (UTC+2) |

| • Summer (DST) | EEST (UTC+3) |

| Postal code | 47x xx |

| Area code(s) | 0482 |

| Vehicle registration | 47 |

| Website |

www www www |

Mardin (Kurdish: Mêrdîn, Syriac: ܡܶܪܕܺܝܢ, Arabic/Ottoman Turkish: ماردين Mārdīn) is a city in southeastern Turkey. The capital of Mardin Province, it is known for the Artuqid (Artıklı or Artuklu in Turkish) architecture of its old city, and for its strategic location on a rocky hill near the Tigris River that rises steeply over the flat plains.[4]

History

Antiquity

The territory of Mardin and Karaca Dağ was known as Izalla in the Late Bronze Age (variously: KURAzalzi, KURAzalli, KURIzalla), an originally Hurrian kingdom.

The city and its surrounds were absorbed into Assyria proper during the Middle Assyrian Empire (1365-1020 BC), and then again during the Neo Assyrian Empire (911-605 BC).[5]

The ancient name was rendered as Izalā in Old Persian, and during the Achaemenid Empire (546-332 BCE) according to the Behistun Inscription it was still regarded as a part of the geo-political entity of Assyria (Achaemenid Assyria, Athura).[6]

It survived into the Assyrian Christian period as the name of Mt. Izala (Izla), on which in the early 4th century AD stood the monastery of Nisibis, housing seventy monks.[7]

In the Roman period, the city itself was known as Marida (Merida),[8][9] from a Syriac/Neo-Aramaic name translating to "fortress".[10][11]

Between c.150 BC and 250 AD (apart from a brief Roman intervention when it became a part of Assyria (Roman province) it became a part of the Neo-Assyrian kingdom of Osroene.[12]

A bishopric of the Assyrian Church of the East was centred on the town when it was part of the Roman province of Assyria. It eventually became part of the Catholic Church in the late 17th century AD following a breakaway from the Assyrian Church, and is still included in the Catholic Church's list of titular sees under the ancient name of the town.[13] It was a suffragan see of Edessa, the province's metropolitan see.

Medieval history

Byzantine Izala fell to the Seljuks in the 11th century. During the Artukid period, many of Mardin's historic buildings were constructed, including several mosques, palaces, madrassas and khans. Mardin served as the capital of one of the two Artukid branches during the 11th and 12th centuries. The lands of the Artukid dynasty fell to the Mongol invasion sometime between 1235 and 1243, but the Artukids continued to govern as vassals of the Mongol Empire.[14] During the battle of Ain Jalut in 1260, the Artukid governor revolted against Mongol rule. Hulegu's general and Chupan's ancestor, Koke-Ilge of the Jalayir, stormed the city and Hulegu appointed the rebel's son, al-Nasir, governor of Mardin. Although, Hulegu suspected the latter's loyalty for a while, thereafter the Artukids remained loyal unlike nomadic Bedoun and Kurd tribes in the south western frontier. The Mongol Ilkhanids considered them important allies. For this loyalty they shown, Artukids were given more lands in 1298 and 1304. Mardin later passed to the Akkoyunlu, a federation of Turkic tribes that controlled territory all the way to the Caspian Sea.

During the medieval period, the town became the centre for episcopal sees of Armenian Apostolic, Armenian Catholic, Assyrian, Syriac Catholic, Chaldean churches, as well as a stronghold of the Syriac Orthodox Church , whose patriarchal see was headquartered in the nearby Saffron Monastery from 1034 to 1924.[15]

Modern history

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1526 | 10,000 | — |

| 1927 | 22,249 | +122.5% |

| 1945 | 18,522 | −16.8% |

| 1950 | 19,354 | +4.5% |

| 1955 | 24,379 | +26.0% |

| 1970 | 33,740 | +38.4% |

| 1990 | 53,005 | +57.1% |

| 2000 | 65,072 | +22.8% |

| 2012 | 86,948 | +33.6% |

In 1517, Mardin was annexed by the Ottomans under Selim I. During this time, Mardin was administered by a governor directly appointed under the Ottoman Sultan's authority. In 1923, with the founding of the Republic of Turkey, Mardin was made the administrative capital of a province named after it.

During World War I Mardin, among other regions close by was one of the sites affected by the Assyrian Genocide and Armenian Genocide. On the eve of World War I, Mardin was home to over 12,000 Syriacs and over 7,500 Armenians.[16] In June 1915, most of the city's Christian notables and its Armenian male population were slaughtered and thrown into caves near Şeyhan. Others were sent to the infamous camps of Ras al-'Ayn, though some managed to escape to the Sinjar Mountain with help from local Chechens.[17] Kurds and Arabs of Mardin typically refer to these events as "fırman" (government order), while Syriac Christians call it "seyfo" (sword).[18] The Syriacs managed to strike a deal with the Turks, sparing them from most of the bloodshed. Unfortunately, the Armenians, Catholics, and Chaldeans who did not manage to escape were massacred in totality, and never came back to the region. Many Assyrian survivors of the violence later on left Mardin for nearby Qamishli in the 1940s after their conscription in the Turkish military became compulsory.[18]

After the last local election, a Syriac Orthodox woman, Februniye Akyol, is serving as co-mayor of the town.

Geology

During the late Permian ~250 mya the Afro-Arabian plate started opening up. The East African continental rift initiation is believed to have started around 27-31 million years ago with the beginning of the basaltic volcanism of the Afar Plume. This rift system would cause a contractional tectonic process to occur in which the Arabian Plate was pushed in a north-easterly direction towards the Eurasian plate. The divergence in the East African Rift would eventually cause the closure of the Tethys Ocean as the Arabian Plate made its first inception of collision with Eurasia between 25-23 million years ago, and complete closure around 10 mya and creation of the Mardin High.

Historical landmarks

Mardin has often been considered an open-air museum due to its historical architecture. Most buildings use the beige colored limestone rock which has been mined for centuries in quarries around the area. The whole city has been listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site under the "Mardin Cultural Landscape".

Churches

- Meryemana (Virgin Mary) Church- A Syriac Catholic Church, built in 1895 as the Patriarchal Church, as the Syriac Catholic see was in Mardin up until the Assyrian Genocide.[19]

- Mor Yusuf (Surp Hovsep; St Joseph) Church - An Armenian Catholic Church[19]

- Mor Behnam (Kırk Şehitler) Church - A Syriac Orthodox Church built in the name of Mor Behnam and Mort Saro, the son and daughter of a ruler; dates back to 569 AD[20]

- Mor Hirmiz Church - A Chaldean Catholic Church in Mardin- It was once the Metropolitan cathedral of the Chaldean Catholic Eparchy of Mardin, prior to it lapsing in 1941. Nevertheless, One Chaldean family remains to maintan it.[21]

- Mor Mihail Church -A Syriac Orthodox Church located on the southern edge of Mardin.

- Mor Simuni Church - A Syriac Orthodox Church with a large courtyard.[22]

- Mor Petrus and Pavlus (SS. Peter and Paul) Church - A 160 year old Assyrian Protestant Church, recently renovated.[23]

- Red (Surp Kevork) Church- An Armenian Apostolic Church recently renovated in 2015[24]

- Mor Cercis Church

- Deyrü'z-Zafaran Monastery or The Monastery of St. Ananias is 5 kilometres south east of the city. The Syriac Orthodox Saffron Monastery was founded in 493 AD and is one of the oldest monasteries in the world and the only one that is still functioning in southern Turkey. From 1160 until 1932, it was the seat of the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch, until the Patriarchate relocated to the Syrian capital Damascus. The site of the monastery itself is said to have been used as a temple by sun worshipers as long ago as 2000 BC.[25][26]

Mosques

- Great Mosque (Ulu Camii) - constructed in the 12th century by the ruler of the Artukid Turks, Qutb ad-din Ilghazi. It has a ribbed dome and a minaret that soars above the city. There were originally two minarets, but one collapsed many centuries ago.

- Melik Mahmut Mosque - built in the 14th century and contains the tomb of its patron Melik Mahmut. It is known for its large gate which features elaborate stonework.

- Abdüllatif Mosque (Latfiye Mosque) - built in 1371 by the Artukid ruler Abdüllatif. Its minaret was destroyed by Tamerlane's army and rebuilt many centuries later in 1845 by the Ottoman Governor Gürcü Mehmet Pasha.

- Şehidiye Medresse and Mosque - built in 1214 by Artuk Aslan. It has an elaborate ribbed minaret and an adjoining madrassa.

- Selsel Mosque

- Necmettin Gazi Mosque

- Kasım Tuğmaner Mosque

- Reyhaniye Mosque - the second largest mosque in Mardin after Ulu Camii. Built in the 15th century, it has a large courtyard and open hallway featuring a fountain.

- Hamidiye Mosque (Zebuni Mosque) - built before the 15th century, it is named after its patron Şeyh Hamit Effendi.

- Süleymanpaşa Mosque

- Secaattin and Mehmet Mosque

- Hamza-i Kebir Mosque

- Şeyh Abdülaziz Mosque

- Melik Eminettin el-Emin Mosque

- Sıtra Zaviye Mosque

- Şeyh Salih Mosque

- Mahmut Türki Mosque

- Sarı Mosque

- Şeyh Çabuk Mosque - built in the 14th century and contains the tomb of its patron Şeyh Çabuk

- Nizamettin Begaz Mosque

- Kale Mosque

- Dinari Mosque

Madrassas

- Zinciriye Medrese (Sultan Isa Medrese) - constructed in 1385 by Najm ad-din Isa. The madrasa is part of a complez that includes a mosque and the tomb of Najm ad-din Isa.

- Sitti Radviyye Medrese (Hatuniye Medrese) - built in the 12th century in the honor of Sitti Radviyye, the wife of Najm ad-din Alpi. There is a footprint that is claimed to be that to be that of the Prophet Muhammad.

- Kasımiye Medrese - construction started by the Artukids and completed by the Akkoyunlu under Sultan Kasım. It has an adjoining Mosque and a Dervish lodge.

Politics

In the 2014 local elections, Ahmet Türk of the Democratic Regions Party (DBP), described as "the most peaceful, most inclusive, most anti-violence, most moderate and wisest figure of the Kurdish political movement, and the one most likely to compromise,"[27] was elected mayor of Mardin. However, on 21 November 2016 he was detained "on terror charges" after being dismissed from office by Turkish authorities, and a trustee appointed as mayor.[28]

Climate

Mardin has a hot-summer Mediterranean climate with hot, dry summers and cold, wet, and occasionally snowy winters. Temperatures in summer usually increase to 40 °C (104 °F) due to Mardin being situated right next to the border of Syria. Snowfall is quite common between the months of December and March, snowing for a week or two. Mardin has over 3000 hours of sun per year. The highest recorded temperature is 42.5 °C (108.5 °F). Average rainfall is about 641.4 mm (25 inches) per year.

Mardin-Kızıltepe, with +48.8 °C (119.84 °F) on August 14, 1993, holds the record for the highest temperature ever recorded in Turkey.[29]

| Climate data for Mardin | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7.4 (45.3) |

9.4 (48.9) |

14.5 (58.1) |

19.6 (67.3) |

26.4 (79.5) |

33.0 (91.4) |

38.1 (100.6) |

37.5 (99.5) |

33.8 (92.8) |

25.6 (78.1) |

17.1 (62.8) |

10.1 (50.2) |

22.71 (72.88) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 3.5 (38.3) |

4.9 (40.8) |

8.7 (47.7) |

14.4 (57.9) |

19.8 (67.6) |

25.4 (77.7) |

30.2 (86.4) |

29.6 (85.3) |

25.7 (78.3) |

18.7 (65.7) |

11.2 (52.2) |

5.0 (41) |

16.42 (61.58) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −0.5 (31.1) |

0.4 (32.7) |

3.5 (38.3) |

8.3 (46.9) |

13.1 (55.6) |

18.2 (64.8) |

22.3 (72.1) |

21.6 (70.9) |

17.1 (62.8) |

11.3 (52.3) |

6.2 (43.2) |

1.2 (34.2) |

10.23 (50.41) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 99.8 (3.929) |

110.7 (4.358) |

94.6 (3.724) |

75.5 (2.972) |

37.7 (1.484) |

8.3 (0.327) |

3.3 (0.13) |

1.2 (0.047) |

4.1 (0.161) |

33.3 (1.311) |

68.7 (2.705) |

104.2 (4.102) |

641.4 (25.25) |

| Average rainy days | 10.6 | 10.6 | 10.7 | 9.9 | 6.6 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.7 | 5.3 | 7.4 | 10.2 | 74.4 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 139.5 | 142.8 | 189.1 | 222 | 310 | 375 | 396.8 | 368.9 | 315 | 238.7 | 174 | 136.4 | 3,008.2 |

| Source: Devlet Meteoroloji İşleri Genel Müdürlüğü[30] | |||||||||||||

Economy

Historically, Mardin produced sesame.[32] Tourism is an important industry in Mardin.

Notable people

- Betül Mardin, businesswoman and activist

- Bülent Tekin, poet and writer

- Masum Türker, former Minister of Finance

- Muammer Güler, governor

- Mümtaz Tahincioğlu, head of TOMSFED

- Murathan Mungan, poet and writer

- Sultan Kösen, the world's tallest living man since 2009, lives in Mardin.[33]

- Zeynel Abidin Erdem, businessman

International relations

Twin towns — Sister cities

Mardin is twinned with:

Gallery

See also

- Mardin Province

- Mardin (Chaldean Diocese)

- Amaseia

- Cappadocia

- Ürgüp

- Artuklu, Mardin

- Maride

- Yazidis in Turkey

References

- ↑ Güsten, Susanne (April 14, 2014). "Mardin elects 25-year old Christian woman as mayor". Al-Monitor.

- ↑ "Area of regions (including lakes), km²". Regional Statistics Database. Turkish Statistical Institute. 2002. Retrieved 2013-03-05.

- ↑ "Population of province/district centers and towns/villages by districts - 2012". Address Based Population Registration System (ABPRS) Database. Turkish Statistical Institute. Retrieved 2013-02-27.

- ↑ , from roughguides.com

- ↑ Parpola - Assyrians after Assyria

- ↑ Besides, in the Behistun inscription, Izalla, the region of Syria renowned for its wine, is assigned to Athura. George Roux - Ancient Iraq

- ↑ Johann Elieser Theodor Wiltsch, trans. John Leitch, Handbook of the Geography and Statistics of the Church, Volume 1, Bosworth & Harrison, 1859, [books.google.ch/books?id=DbwpAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA232 p. 232.]

- ↑ "Mardin". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Fraternité Chrétienne Sarthe-Orient, "Marida (Mardin)"

- ↑ Lipiński, Edward (2000). The Aramaeans: their ancient history, culture, religion. Peeters Publishers. p. 146. ISBN 978-90-429-0859-8.

- ↑ Smith, of R. Payne Smith. Ed. by J. Payne (1998). A compendious Syriac dictionary : founded upon the Thesaurus Syriacus (Repr. ed.). Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns. p. 299. ISBN 978-1-57506-032-3. Retrieved 8 March 2013. suggesting Mardin as a plural "fortresses".

- ↑ Amir Harrak". Journal of Near Eastern Studies 51 (3): 209–214. 1992. doi:10.1086/373553. JSTOR 545546.

- ↑ Annuario Pontificio 2013 (Libreria Editrice, 2013, ISBN 978-88-209-9070-1), p. 923

- ↑ Ed. Morris Rossabi - China among equals: the Middle Kingdom and its neighbors, 10th-14th centuries, p. 244

- ↑ Cinti Migliarini, Anita. "La chiesa siriaca di Antiochia". Chiesa siro-ortodossa di Antiochia (in Italian). Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- ↑ Kevorkian, Raymond (2011). The Armenian Genocide: a Complete History. London: Tauris. p. 371.

- ↑ Kevorkian, Raymond (2011). The Armenian Genocide: a Complete History. London: Tauris. pp. 375–376.

- 1 2 Biner, Zerrin Özlem (Fall–Winter 2010). "Acts of Defacement, Memory of Loss: Ghostly Effects of the "Armenian Crisis" in Mardin, Southeastern Turkey". History and Memory.

- 1 2 "Mardin - Duane Alexander Miller's Blog". Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ Philandre (6 October 2013). "Sunday Service, Syriac Orthodox Church of the Forty Martyrs, Mardin, Turkey.". Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ "St Hirmiz Chaldean Church in Mardin, Turkey". 2 June 2015. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ simpsonturkishadventures.blogspot.com/2013/03/easter-in-mardin.html

- ↑ "Renovated Protestant church in Mardin to open soon". Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ "Mardin Surp Kevork Kilisesi için Kitap Kermesi ve Söyleşi". Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ SOR (2000-04-19). "Dayro d-Mor Hananyo: Erstwhile seat of the Syriac Orthodox Patriarch". Sor.cua.edu. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ↑ "ARTS-CULTURE - Syriac monastery dated back to 4,000 years". Hurriyetdailynews.com. 2010-01-03. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ↑ "The final nail in the coffin of peace process in Turkey". Al-Monitor. 22 November 2016.

- ↑ "Court arrests former Mardin mayor Ahmet Türk". Hurriyet Daily News. 24 November 2016.

- ↑ "Sıkça Sorulan Sorular - Meteoroloji Genel Müdürlüğü".

- ↑ http://www.dmi.gov.tr/veridegerlendirme/il-ve-ilceler-istatistik.aspx?m=MARDIN

- ↑ "Resmi İstatistikler (İllerimize Ait İstatistiki Veriler)". MGM.

- ↑ Prothero, W.G. (1920). Armenia and Kurdistan. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 62.

- ↑ Satter, Raphael (16 Sept 09). "8'1" Turk takes title of world's tallest man". Retrieved 17 Sept 09. Check date values in:

|access-date=, |date=(help) - ↑ "Medmestno in mednarodno sodelovanje". Mestna občina Ljubljana (Ljubljana City) (in Slovenian). Retrieved 2013-07-27.

Sources

- Ayliffe, Rosie, et al.. (2000) The Rough Guide to Turkey. London: Rough Guides.

- Gaunt, David: Massacres, Resistance, Protectors: Muslim-Christian Relations in Eastern Anatolia During World War I, Gorgias Press, Piscataway (NJ) 2006 I

- Grigore, George (2007), L'arabe parlé à Mardin. Monographie d'un parler arabe périphérique. Bucharest: Editura Universitatii din Bucuresti, ISBN 978-973-737-249-9[1]

- Jastrow, Otto (1969), Arabische Textproben aus Mardin und Asex, in "Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft" (ZDMG) 119 : 29-59.

- Jastrow, Otto (1992), Lehrbuch der Turoyo-Sprache in "Semitica Viva – Series Didactica", Wiesbaden : Otto Harrassowitz.

- Minorsky, V. (1991), Mārdīn, in "The Encyclopaedia of Islam". Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- Niebuhr, Carsten (1778), Reisebeschreibung, Copenhagen, II:391-8

- Shumaysani, Hasan (1987), Madinat Mardin min al-fath al-'arabi ila sanat 1515. Bayrūt: 'Ālam al-kutub.

- Tavernier, Jean-Baptiste (1692), Les six voyages, I:187

- Sasse, Hans-Jürgen (1971), Linguistische Analyse des Arabischen Dialekts der Mhallamīye in der Provinz Mardin (Südossttürkei), Berlin.

- Socin, Albert (1904), Der Arabische Dialekt von Mōsul und Märdīn, Leipzig.

- della Valle, Pietro (1843), Viaggi, Brighton, I: 515

- Wittich, Michaela (2001), Der arabische Dialekt von Azex, Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mardin. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Mardin. |

- The Spoken Arabic of Mardin

- Mardin Weather Forecast Information

- Mardin Guide and Photo Album

- First International Symposium of Mardin History

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Mardin". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Mardin". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.