Caning

| Part of a series on |

| Corporal punishment |

|---|

|

| By place |

| By implementation |

| By country |

| Court cases |

| Politics |

Rattan cane |

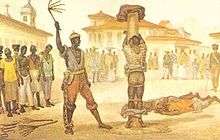

Caning is a form of corporal punishment consisting of a number of hits (known as "strokes" or "cuts") with a single cane usually made of rattan, generally applied to the offender's bare or clothed buttocks (see spanking) or hand(s) (on the palm). Caning on the knuckles or shoulders is much less common. Caning can also be applied to the soles of the feet (foot whipping or bastinado). The size and flexibility of the cane and the mode of application, as well as the number of the strokes, vary greatly — from a couple of light strokes with a small cane across the seat of a junior schoolboy's trousers, to 24 very hard, wounding cuts on the bare buttocks with a large, heavy, soaked rattan as a judicial punishment in some Southeast Asian countries.

The thin cane generally used for corporal punishment is not to be confused with a walking stick, sometimes also called (especially in American English) a "cane" but which is thicker and much more rigid, and more likely to be made of stronger wood than of cane.

Scope of use

Caning was a common form of judicial punishment and official school discipline in many parts of the world in the 19th and 20th centuries. Corporal punishment (with a cane or any other implement) has now been outlawed in much, but not all, of Europe.[1] However, caning remains legal in numerous other countries in home, school, religious, judicial or military contexts, and is also in common use[2] in some countries where it is no longer legal.

Judicial corporal punishment

Judicial caning, administered with a long, heavy rattan and much more severe than the canings given in schools, was/is a feature of some British colonial judicial systems, though the cane was never used judicially in Britain itself (the specified implements there, until abolition in 1948, being the birch and the cat-o'-nine-tails). In some countries caning is still in use in the post-independence era, particularly in Southeast Asia (where it is now being used far more than it was under British rule), and in some African countries.

The practice is retained, for male offenders only, under the criminal law in Malaysia, Singapore and Brunei.[3] (In Malaysia there is also a separate system of religious courts for Muslims only, which can order a much milder form of caning for women as well as men.) Caning in Indonesia is a recent introduction, in the special case of Aceh, on Sumatra, which since its 2005 autonomy has introduced a form of sharia law for Muslims only (male or female), applying the cane to the clothed upper back of the offender.[4]

African countries still using judicial caning include Botswana, Tanzania, Nigeria (mostly in northern states,[5] but few cases have been reported in southern states[6][7][8][9]) and, for juvenile offenders only, Swaziland and Zimbabwe. Other countries that used it until the late 20th century, generally only for male offenders, included Kenya, Uganda and South Africa, while some Caribbean countries such as Trinidad and Tobago use birching, another punishment in the British tradition, involving the use of a bundle of branches, not a single cane.

In Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei, healthy males under 50 years of age can be sentenced to a maximum of 24 strokes of the rotan (rattan) cane on the bare buttocks; the punishment is mandatory for many offences, mostly violent or drug crimes, but also immigration violations, sexual offences and (in Singapore) acts of vandalism. It is also imposed for certain breaches of prison rules. In Aceh caning can be imposed for adultery.[10] The punishment is applied to foreigners and locals alike.

Two examples of the caning of foreigners which received worldwide media scrutiny are the canings in Singapore in 1994 of Michael P. Fay, an American student who had vandalised several automobiles, and in the United Arab Emirates in 1996 of Sarah Balabagan, a Filipina maid convicted of homicide.

Caning is also used in the Singapore Armed Forces to punish serious offences against military discipline, especially in the case of recalcitrant young conscripts. Unlike judicial caning, this punishment is delivered to the soldier's clothed buttocks. See Caning in Singapore#Military caning.

School corporal punishment

The frequency and severity of canings in educational settings have varied greatly, often being determined by the written rules or unwritten traditions of the school. The western educational use of the cane dates principally to the late nineteenth century, gradually replacing birching—effective only if applied to the bare bottom—with a form of punishment more suited to contemporary sensibilities, once it had been discovered that a flexible rattan cane can provide the offender with a substantial degree of pain even when delivered through a layer of clothing.

Caning as a school punishment is strongly associated in the English-speaking world with England, but it was also used in other European countries in earlier times, notably Scandinavia, Germany and the countries of the former Austrian empire.

In some schools corporal punishment was administered solely by the headmaster, while in others the task was delegated to other teachers. In many English and Commonwealth private schools, authority to punish was also traditionally given to certain senior students (often called prefects). In the early 20th century, such permission for prefects to cane other boys was widespread in British public schools. The perceived advantages of this were promptness of punishment and avoiding bothering the teaching staff with minor disciplinary matters. Canings from prefects took place for a wide variety of failings, including lack of enthusiasm in sport, with the punishment repeated, if necessary, until the younger boy's performance or attitude improved.[11] From at least the late 19th century onwards, prefects had also used canings to enforce youngsters' participation in other character-building aspects of public school life, such as compulsory cold baths in winter.[12]

Another claimed advantage was that boys who misbehaved would be chastised more effectively by receiving a caning from a prefect than from a teacher, because pupils associate more closely with each other than with teachers, and thus the impact would be better known in the culprit's immediate peergroup.[13] Such systems were not limited to secondary age pupils. From at least the early 1860s onwards, some private preparatory schools relied heavily on "self-government" by prefects for even their youngest pupils (around eight years old), with caning the standard punishment for even minor offences. It was regarded as having "no sense of indignity" for the recipient of the punishment.[14]

As early as the 1920s, the tradition of prefects at British public schools repeatedly caning new boys for trivial offences was criticised by psychologists as producing "a high state of nervous excitement" in some of the youngsters subjected to it. It was felt that granting untrained and unsupervised older adolescents the power to impose comprehensive thrashings on their younger schoolmates whenever they chose, might have adverse psychological effects.[15]

Some British private schools still permitted caning to be administered by prefects in the 1960s, with opportunities for it provided by complex sets of rules on school uniform and behaviour.[16] In 1969, when the question was raised in Parliament, it was thought that relatively few schools still permitted this.[17] By contrast, caning in British state schools in the later 20th century was often, in theory at least, administered by the head teacher only. Canings for primary school age pupils at state schools in this period could be extremely rare; one study found that over an eight-year timespan, one head teacher had only caned two boys in total, but made more frequent use of slippering, while another had caned no pupils at all.[18]

Like their British counterparts, South African private schools also gave prefects free rein to administer canings whenever they felt it appropriate, from at least the late 19th century onwards.[19] South African schools continued to use the cane to emphasise sporting priorities well into the late 20th century, caning boys for commonplace gameplay errors such as being caught offside in an association football match, as well as for poor batting performance in cricket, not applauding their school team's performance sufficiently, missing sport practice sessions, or even "to build up team spirit".[20] The use of corporal punishment within the school setting was prohibited by the South African Schools Act of 1996. According to Chapter 2 Section 10 of the act, (1) No person may administer corporal punishment at a school to a learner and (2) Any person who contravenes subsection (1) is guilty of an offence and liable on conviction to a sentence, which could be imposed for assault.[21]

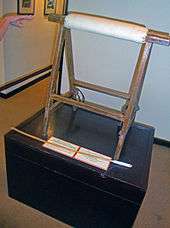

In many state secondary schools in England and Wales it was in use, mostly for boys, until 1987,[22] while elsewhere other implements prevailed, such as the Scottish tawse. The cane was generally administered in a formal ceremony to the seat of the trousers, typically with the student bending over a desk or chair. Usually there was a maximum of six strokes (known as "six of the best"). Such a caning would typically leave the offender with uncomfortable weals and bruises lasting for many days after the immediate intense pain had worn off. A headmaster's caning of a 13-year-old schoolboy at an English grammar school in 1987—five strokes for poor exam results—left "severe bruising", and, according to the family doctor, five separate weals. The headmaster who gave the punishment was cleared of the offence of assault occasioning actual bodily harm, with the judge commenting "If you get a beating you must expect it to be with force."[23]

Schoolgirls were caned much more rarely than boys, and if the punishment was given by a male teacher, nearly always on the palm of the hand. Rarely, girls were caned on the clothed bottom, in which case the punishment would probably be applied by a female teacher.

Caning as a school punishment for boys is still routine in a number of former British territories including Singapore,[24] Malaysia and Zimbabwe. See Caning in Singapore#School caning. Until recently it had also been common in Australia (now banned in public schools; and abolished in practice (though not strictly in theory) by the vast majority of all independent schools),[25] New Zealand (banned from 1990)[26] and South Africa (banned in public and private schools alike from 1996).[27] In the UK, all corporal punishment in private schools was finally banned in 1999 for England and Wales,[28] 2000 in Scotland,[29][30] and 2003 in Northern Ireland.[31]

In Malaysia, although the Education Ordinance 1957 specifically outlaws the caning of girls in school,[32] the caning of girls, usually on the palm of the hand, is still rather common, especially in primary schools but also occasionally in secondary schools, sometimes even for minor mistakes like being unable to answer questions correctly.[33][34][35][36][37] In November 2007, in response to a perceived increase in indiscipline among female students, the National Seminar on Education Regulations (Student Discipline) passed a resolution recommending allowing the caning of female students at school.[38] The resolution is currently in its consultation process.

The cane was also used more or less frequently on boy inmates at the British youth reformatories known from 1933 to 1970 as Approved Schools, and rarely for girls in such schools. In Approved schools the cane was applied to the buttocks for boys and to the hands for girls, but after Approved Schools became "Community Homes with Education" under the Children and Young Persons Act 1969,[39] girls could be caned on the buttocks.[40] Caning is still used in the equivalent institutions in some countries, such as Singapore and Guyana.

In 19th-century France it was dubbed "The English Vice", probably because of its widespread use in British schools.[41] The regular depiction of caning in British novels about school life from the 19th century onwards, as well as movies such as If...., which includes a dramatic scene of boys caned by prefects, contributed to the French perception of caning as being central to the British educational system.[42] Caning was not unknown for French boys in the 19th century, but they were described as "extremely sensitive" to corporal punishment and tended to make a fuss about its imposition.[43]

Member states of the Convention on the rights of the child are obliged to "take all appropriate legislative, administrative, social and educational measures to protect the child from all forms of physical or mental violence, injury or abuse."

Domestic corporal punishment

Also known as domestic corporal punishment, parents can cane a child as a punishment for disobedience, which is a common practice in some Asian countries such as Singapore, China, Malaysia, and others. See Caning in Singapore.

Voluntary use

Caning may also be a part of consensual sadomasochistic activities.

Effects

Caning with a heavy judicial rattan as used in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei can leave scars for years if a large number of strokes are inflicted. However, most ordinary canings with a typical light rattan (used at home for punishing children or at school for punishing students), although painful at the time, leave only reddish welts or bruises lasting a few days. One boy caned at Winchester College in the early 1930s said that "it was, of course, disagreeable, but left no permanent scars on my personality or my person".[44]

When caning was widespread in schools in the United Kingdom, it was perceived that a caning on the hand carried a greater risk of injury than a caning on the buttocks; in 1935 an Exeter schoolboy won £1 in damages (equivalent to £63 in 2015), plus his medical expenses, from a schoolmaster, when the county court decided that an abscess that developed on his hand was the result of a caning.[45]

See also

- Birching

- Caning in Malaysia

- Caning in Singapore

- Eton College

- Flagellation

- Judicial corporal punishment

- Paddle (spanking)

- School corporal punishment

- Foot whipping

- Spanking

Notes

- ↑ C. Farrell. "Corporal Punishment in British schools". Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ↑ "Caning Students, still!". The Daily Star. Dhaka. 11 April 2011. Retrieved 15 April 2011.

- ↑ Judicial caning in Singapore, Malaysia and Brunei at World Corporal Punishment Research.

- ↑ Afrida, Nani. "Public canings to start in Aceh for gamblers", The Jakarta Post, 23 June 2005.

- ↑ Nossiter, Adam (8 February 2014). "Nigeria Tries to 'Sanitize' Itself of Gays". The New York Times.

- ↑ Article 18 of the Criminal Code ACt 1916; Article 386(1) of the Criminal Procedure Act 1945.

- ↑ "Nigeria: Judicial CP". World Corporal Punishment Research. November 2014.

- ↑ "Man, 25, gets 12 strokes for stealing". The Tide. Port Harcourt. 31 July 2008.

- ↑ Anofochi, Valerie (3 August 2011). "Court orders that undergraduate be flogged for theft". The Daily Times. Lagos.

- ↑ Bachelard, Michael (7 May 2014). "Aceh woman, gang-raped by vigilantes for alleged adultery, now to be flogged". The Age (Melbourne).

- ↑ Savage, Howard James (1927). Games and sports in British schools and universities. New York: The Chicago foundation for the advancement of teaching. p. 43. OCLC 531804.

- ↑ Lynch, Bohun (1922). Max Beerbohm in perspective. New York: Knopf. p. 5. OCLC 975960.

- ↑ National and English Review. London. 5: 719. 1885. ISSN 0952-6447. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ The Education outlook. London: S. Birch. 59: 31–32. 1906. OCLC 291230258. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ The Journal of mental science. London: Churchill. 68: 221. 1922. ISSN 0368-315X. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ The Listener. 111. London: BBC. 1984. p. 10. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Payne, Sara (14 February 1969). "Rods in young hands". Times Educational Supplement. London.

- ↑ King, Ronald (1989). The Best of Primary Education?: A sociological study of junior middle schools. London: Falmer. p. 53. ISBN 978-1-85000-602-2.

- ↑ Morrell, Robert (2001). From Boys to Gentlemen: Settler masculinity in Colonial Natal, 1880-1920. Pretoria: Unisa Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-86888-151-2.

- ↑ Holdstock, T. Len (1987). Education for a new nation. Riverclub: Africa Transpersonal Association. p. 172. ISBN 978-0-620-11721-0.

- ↑ South African Schools Act, 1996, Chapter 2 : Learners, Section 10. Prohibition of corporal punishment

- ↑ Gould, Mark (9 January 2007). "Sparing the rod". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 18 May 2011.

- ↑ Deves, Keith (21 July 1987). "Caning storm head is cleared". The Sun. London.

- ↑ See Singapore school handbooks at World Corporal Punishment Research.

- ↑ Country files - Australia: School CP at World Corporal Punishment Research.

- ↑ Education Act, 1989. New Zealand State Report at GITEACPOC.

- ↑ "Assembly passes new schools bill", Cape Times, 30 October 1996.

- ↑ Brown, Colin (25 March 1998). "Last vestiges of caning swept away". The Independent. London.

- ↑ Buie, Elizabeth (8 July 1999). "Education Bill welcomed but Tories will fight return of opted-out school to the fold". The Herald. Glasgow.

- ↑ "Standards in Scotland's Schools etc. Act 2000, s.16".

- ↑ Torney, Kathryn (27 June 2003). "Ulster schools defying slap ban". Belfast Telegraph.

- ↑ Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia 2003. Surat Pekeliling Iktisas Bil 7:2003 - Kuasa Guru Merotan Murid. Retrieved 4 June 2007. (Malay)

- ↑ Uda Nagu, Suzieana (21 March 2004). "Spare the rod?". New Straits Times. Kuala Lumpur.

- ↑ Chin, V.K. (4 December 2007). "Caning of schoolgirls is nothing new". The Star. Kuala Lumpur.

- ↑ Lau Lee Sze (29 November 2007). "Girls should be caned too but do it right". The Star. Kuala Lumpur.

- ↑ Chew, Victor (26 July 2008). "Use the cane only as a last resort, teachers". The Star. Kuala Lumpur.

- ↑ "Parents have to be totally involved". The Star. Kuala Lumpur. 22 February 2012.

- ↑ Chew, Sarah (28 November 2007). "Education seminar passes resolution to cane female students". The Star. Kuala Lumpur.

- ↑ Langan, Mary. Welfare: needs, rights, and risks, Routledge, London, 1998. ISBN 978-0-415-18128-0

- ↑ Healy, Pat (20 May 1981). "Caning of girls 'worse than in last century'". The Times. London.

- ↑ Gibson, Ian (1978). The English vice: Beating, sex, and shame in Victorian England and after. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0-7156-1264-6.

- ↑ Blackwood's Magazine. Edinburgh: William Blackwood. 328: 522. 1980. ISSN 0006-436X. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Hope, Ascott Robert (1882). A book of boyhoods. London: J. Hogg. p. 154. OCLC 559876116.

- ↑ "Charles Chenevix Trench". The Daily Telegraph. London. 29 November 2003. Retrieved 19 December 2013.

- ↑ "Richer for caning". Gloucester Citizen. 15 June 1935. Retrieved 23 July 2014. (subscription required (help)).

References

- Hardy, Janet (2004). The Toybag Guide to Canes and Caning (Toybag Guide). San Francisco: Greenery Press. ISBN 1-890159-56-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Caning. |

- Video clips of judicial caning in Malaysia (warning – very graphic)

- Video clips of schoolboy caning in Singapore

- Corporal punishment in British schools at World Corporal Punishment Research