Capture of Kassala

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

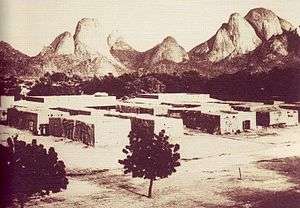

The Capture of Kassala in Sudan, occurred on 4 July 1940, during early engagements between Italian and Anglo-Sudanese forces in the East African Campaign.

Background

Africa Orientale Italiana

.svg.png)

On 9 May 1936, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini proclaimed Africa Orientale Italiana (AOI), formed from Ethiopia after the Second Italo-Abyssinian War and the colonies of Italian Eritrea and Italian Somaliland.[1] Amedeo, Duke of Aosta, had been appointed the Viceroy and Governor-General of the AOI in November 1937, with headquarters in Addis Ababa, the Ethiopian capital. On 1 June 1940, as the commander in chief of Comando Forze Armate dell'Africa Orientale Italiana (Italian East African Armed Forces Command) and Generale d'Armata Aerea (General of the Air Force), Aosta had about 290,476 local and metropolitan troops (including naval and air force personnel) available. (By 1 August, mobilisation had increased the number to 371,053 troops.)[2]

On 31 March 1940, Mussolini laid down a defensive strategy against Kenya and limited offensives against Kassala and Gedaref in Sudan; on 10 June, he declared war on Britain and France, which made Italian military forces in Libya a threat to Egypt and those in the AOI a danger to the British and French colonies in East Africa. Italian belligerence led to the closure of the Mediterranean to Allied merchant ships and endangered British supply routes along the coast of East Africa, the Gulf of Aden, Red Sea and the Suez Canal.[3][lower-alpha 1]

On 10 June, the Italian army in the AOI was organised in four commands, the Northern Sector in the vicinity of Asmara, Eritrea (Lieutenant-General Luigi Frusci), the Southern Sector around Jimma, Ethiopia (General Pietro Gazzera), the Eastern Sector on the border with French Somaliland and British Somaliland (General Guglielmo Nasi) and the Giuba Sector covering southern Somalia near Kismayo, Italian Somaliland (Lieutenant-General Carlo De Simone). Italy was far from ready for a long war or the occupation large areas of Africa.[4]

Mediterranean and Middle East Theatre

The British had based forces in Egypt since 1882 but these were greatly reduced by the terms of the treaty of 1936. A small British and Commonwealth force garrisoned the Suez Canal and the Red Sea route to India the Far East. In mid-1939, General Archibald Wavell was appointed General Officer Commanding-in-Chief (GOC-in-C) of the new Middle East Command, over the Mediterranean and Middle East theatres.[5] Wavell had about 86,000 troops at his disposal for Libya, Iraq, Syria, Iran and East Africa.[6] Wavell was responsible for the defence of Egypt through the General Officer Commanding-in-Chief, British Troops Egypt, training the Egyptian army and the co-ordination of military operations with the Mediterranean Naval and Air Force chiefs and regional military commanders.[7]

Before the beginning of the war, the British detected increases in the number of Italian troops on the Sudan border and assumed that if they attacked, Khartoum the seat of government 300 mi (480 km) to the west of the Eritrean frontier, Atbara the junction of railways to Khartoum, 200 mi (320 km) from the border and Port Sudan with the only heavy workshops in the country and the only decent port would be the objectives. The ground was arid and had no all-weather roads but in the dry weather before the monsoon in June or July, was motorable nearly everywhere.[8]

Prelude

Sudan

In 1940, the British had three infantry battalions in Sudan and the Sudan Defence Force (SDF), which had 4,500 men in 21 companies, the best-equipped being Motor Machine-Gun companies, with light machine-guns mounted in vans and lorries and a few locally made armoured cars. The Sudan Horse was converting to a 3.7-inch mountain howitzer battery. The Sudan commander, Lieutenant-General William Platt put one British battalion in Khartoum, one at Atbara and the third at Gebeit and Port Sudan. The SDF garrisoned the frontier with the provincial police and a motley of irregular scouts to watch, harass and delay the Italians. Should the Italians invade, the dispersed units would converge against the attackers. The SDF mounted frequent patrols and raids over the Eritean and Ethiopian borders, particularly near Kassala and Gallabat, lifting prisoners, inflicting casualties and gaining confidence.[9]

Italian preparations

After the declaration of war on 10 June 1940, the Italian forces in the AOI raided over the Sudanese border and Italian aircraft bombed Kassala, Port Sudan, Atbara, Kurmuk and Gedaref.[9]The attack on Kassala was planned and led by General Luigi Frusci, governor of Eritrea and Amhara, assisted by General Vincenzo Tessitori (who took command of one of the columns). The Italian and colonial forces were divided into three columns, Gulsa east, Gulsa west (the only one equipped with trucks) and Central, supported by the Regia Aeronautica (Italian Royal Air Force); some cavalry squadrons acted as vanguards.

Battle

At 3:00 a.m. on 4 July 1940, three Italian columns, about 19–22 miles (31–36 km) apart, started their attack on Kassala. The cavalry, led by Lieutenant Francesco Santasilia, bypassed Mount Kasala and Mount Mocram and launched the first attack.[10] Kassala was defended by a small garrison of the Sudan Defence Force (SDF), which opposed a determined resistance and counter-attacked with twenty tanks, which caused the Italian Air Force to intervene. At 1:00 p.m., the Italian cavalry squadrons entered Kassala, and the Anglo-Sudanese units withdrew.[11] Italian casualties numbered 117 men.[12] Pietro Gazzera occupied the fort of Gallabat and Kurmuk in Sudan. Gallabat was placed under the command of Colonel Castagnola, who built a solid system of defence. No further Italian advance into Sudan took place, as there was no fuel available.

Aftermath

After capturing Kassala, the Italian commands fortified the city with anti-tank defences, machine-gun posts, and strong-points, ultimately establishing a brigade-sized garrison (the 12th Colonial Brigade); they were however disappointed to find no strong anti-British sentiment among the native population.[13][14]

Subsequent operations

Gallabat

Gallabat fort lay in Sudan and Metemma a short way across the Ethiopian border beyond the Boundary Khor, a dry river bed with steep banks covered by long grass. Both places were surrounded by field fortifications and Gallabat was held by a colonial infantry battalion. Metemma had two colonial battalions and a banda formation, all under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Castagnuola. The 10th Indian Infantry Brigade, a field artillery regiment, B Squadron, 4th RTR with six Infantry tanks and six light tanks, attacked Gallabat on 6 November at 5:30 a.m. An RAF contingent of six Wellesley bombers and nine Gladiator fighters, were thought sufficient to overcome the 17 Italian fighters and 32 bombers believed to be in range.[15] The infantry assembled 1–2 mi (1.6–3.2 km) from Gallabat, whose garrison was unaware that an attack was coming, until the RAF bombed the fort and put the wireless out of action. The field artillery began a simultaneous bombardment and after an hour changed target and bombarded Metemma. The night previous, the 4th/ 10th Baluch Regiment occupied a hill overlooking the fort as a flank guard. The troops on the hill covered the advance at 6:40 a.m. of the 3rd Royal Garwhal Rifles followed by the tanks. The Indians reached Gallabat and fought hand-to-hand with Granatieri di Savoia and some Eritrean troops in the fort. At 8:00 a.m. the 25th and 77th Colonial battalions counter-attacked and were repulsed but three British tanks were knocked out by mines and six by mechanical failures caused by the rocky ground.[16]

The defenders at Boundary Khor were dug in behind fields of barbed wire and Castagnuola had contacted Gondar for air support. Italian bombers and fighters attacked all day, shot down seven Gladiators for a loss of five Fiat CR-42s and destroyed the lorry carrying spare parts for the tanks. The ground was so hard and rocky that there were no trenches and when Italian bombers made their biggest attack, the infantry had no cover. An ammunition lorry was set on fire by burning grass and the sound was taken to be an Italian counter-attack from behind. When a platoon advanced towards the sound with fixed bayonets, some troops thought that they were retreating.[17] Part of the 1st Battalion, Essex Regiment at the fort broke and ran, carrying some of the Gahrwalis with them. Many of the British fugitives mounted their transport and drove off, spreading the panic and some of the runaways reached Doka before being stopped.[16][lower-alpha 2] The Italian bombers returned next morning and Slim ordered a withdrawal from Gallabat Ridge 3 mi (4.8 km) west to less exposed ground that evening. Sappers from the 21st Field Company remained behind to demolish the remaining buildings and stores in the fort. The artillery bombarded Gallabat and Metemma and set off Italian ammunition dumps full of pyrotechnics. British casualties since 6 November were 42 men killed and 125 wounded.[18]

The brigade patrolled to deny the fort to the Italians and on 9 November, two Baluch companies attacked and held the fort during the day and retired in the evening. During the night an Italian counter-attack was repulsed by artillery-fire and next morning the British re-occupied the fort unopposed. Ambushes were laid and prevented Italian reinforcements from occupying the fort or the hills on the flanks despite frequent bombing by the Regia Aeronautica.[17] The brigade re-occupied the ridge three days later but made no attack on Metemma.[19] The caravan routes into Ethiopia needed to supply the Arbegnoch remained under Italian control. For two months, the 10th Indian Brigade and then the 9th Indian Brigade simulated a division, the slouch hats of the Garhwalis being mistaken as a sign that an Australian division had arrived.[20] The brigades blazed lines of communication eastwards 80 mi (130 km) from Gedaref and created dummy airfields and stores depots, to convince Italian Intelligence that the British offensive from Sudan would be towards Gondar on the south and that the real attack at Kassala into Eritrea was a bluff.[21]

Gazelle Force

In September 1940, the 5th Indian Infantry Division (Major-General Lewis Heath) began to arrive in Sudan, Platt held back the 29th Indian Infantry Brigade (Brigadier John Marriott) around Port Sudan and the rest with attachments from the SDF was ordered to prevent an Italian advance on Khartoum from Goz Regeb on the Atbara river to Gallabat, a front of about 200 mi (320 km). Gazelle Force (Colonel Frank Messervy), based on Skinner's Horse, No. 1 Motor Machine-Gun Group of the SDF and a varying amount of field and horse artillery, was assembled near Kassala to probe forwards, to harass the Italians and keep them off-balance to make an impression of a much larger force and encourage a defensive mentality. By using the term Five instead of 5th in all communications, managed to persuade Italian military intelligence that five Indian divisions occupied the 5th Indian Division area.[22]

In November, after the failed British attack at Gallabat, Gazelle Force operated from the Gash river delta against Italian advanced posts around Kassala on the Ethiopian plateau, to the extent that Aosta ordered the Lieutenant-General Luigi Frusci, the commander of the Northern Sector to challenge the British raiders. Two Italian battalions conducted a desultory engagement against Gazelle Force 30 mi (48 km) north of Kassala for about two weeks and then withdrew.[23] In Rome, the new Capo di Stato Maggiore Generale (Chief of the Italian Supreme Command) General Ugo Cavallero had after 6 December, urged the abandonment of plans to invade Sudan, to defend the AOI.[24] From early January, signs appeared that the Italians were reducing the number of troops on the Sudan frontier and a withdrawal from Kassala seemed possible.[25]

News of the Italian disaster in Operation Compass in Egypt, hit-and-run attacks by Gazelle Force and the activities of Mission 101 in Ethiopia, led Frusci to become apprehensive about the northern route to Kassala. On 31 December, the troops on the northern flank withdrew behind Sabdaret, with patrols forward at Serobatib and Adardet and a mobile column in Sabdaret for contingencies. Frusci was ordered to retire from Kassala and Metemma to the passes from Agordat to Gondar but objected on grounds of prestige and proclaimed that the imminent British attack would be scattered. On 17 January, the 12th Colonial Brigade withdrew from Kassala and Tessenei, to the triangle formed by the northern and southern roads from Kassala at Keru, Giamal Biscia and Aicota.[26][27]

Notes

- ↑ The Kingdom of Egypt remained neutral during World War II but the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 allowed the British to occupy Egypt and Anglo-Egyptian Sudan.[3]

- ↑ The battalion was eventually replaced by the 2nd Highland Light Infantry and fought in Syria and Iraq.[16]

Footnotes

- ↑ Playfair 1954, p. 2.

- ↑ Playfair 1954, p. 93.

- 1 2 Playfair 1954, pp. 6–7, 69.

- ↑ Playfair 1954, pp. 38–40.

- ↑ Playfair 1954, pp. 19, 93.

- ↑ Dear & Foot 2005, p. 245.

- ↑ Raugh 1993, pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Playfair 1954, p. 168.

- 1 2 Playfair 1954, pp. 169–170.

- ↑ Del Boca 1986, p. 356.

- ↑ Maioli & Baudin 1974, p. 134.

- ↑ Playfair 1954, p. 170.

- ↑ Playfair 1954, pp. 170–171.

- ↑ Stegemann & Vogel 1995, p. 295.

- ↑ Playfair 1954, p. 398.

- 1 2 3 Mackenzie 1951, p. 33.

- 1 2 Brett-James 1951, ch 2.

- ↑ Playfair 1954, p. 399.

- ↑ Mackenzie 1951, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Mackenzie 1951, p. 34.

- ↑ Mackenzie 1951, p. 43.

- ↑ Raugh 1993, p. 172.

- ↑ Raugh 1993, pp. 172–174.

- ↑ Mackenzie 1951, p. 42.

- ↑ Playfair 1954, pp. 397, 399.

- ↑ Raugh 1993, pp. 172–174, 175.

- ↑ Mackenzie 1951, pp. 42–44.

References

- Brett-James, Antony (1951). Ball of Fire – The Fifth Indian Division in the Second World War. Aldershot: Gale & Polden. OCLC 4275700. Retrieved 5 March 2016.

- Dear, I. C. B. (2005) [1995]. Foot, M. R. D., ed. Oxford Companion to World War II. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280670-3.

- Del Boca, Angelo (1986). Italiani in Africa Orientale: La caduta dell'Impero [Italians in East Africa: The Fall of the Empire] (in Italian). III. Roma-Bari: Laterza. ISBN 88-420-2810-X.

- Mackenzie, Compton (1951). Eastern Epic: September 1939 – March 1943 Defence. I. London: Chatto & Windus. OCLC 59637091.

- Maioli, G.; Baudin, J. (1974). Vita e morte del soldato italiano nella guerra senza fortuna: La strana guerra dei quindici giorni [Life and Death of Italian Soldiers in the War with no Luck: The Strange War of Fifteen Days]. Amici della storia. I. 18 volumes, 1973–1974. Ginevra: Ed. Ferni. OCLC 716194871.

- Playfair, Major-General I. S. O.; et al. (1954). Butler, J. R. M., ed. The Mediterranean and Middle East: The Early Successes Against Italy (to May 1941). History of the Second World War, United Kingdom Military Series. I. HMSO. OCLC 494123451. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- Raugh, H. E. (1993). Wavell in the Middle East, 1939–1941: A Study in Generalship. London: Brassey's UK. ISBN 0-08-040983-0.

- Stegemann, Bernd; Vogel, Detlef (1995). Germany and the Second World War: The Mediterranean, South-East Europe and North Africa, 1939–1941. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-822884-8.

Further reading

- Petacco, Arrigo (2003). Faccetta nera: storia della conquista dell'impero [Black Facets: History of the Conquest of the Empire]. Le scie. Milano: Edizioni Mondadori. ISBN 978-8-80451-803-7.