Charvet Place Vendôme

| |

| Privately held company | |

| Industry | fashion |

| Founded | Paris, France 1838 |

| Founder | Christofle Charvet |

| Headquarters | Paris, France |

Key people |

Anne-Marie Colban, director Jean-Claude Colban, director |

| Products | shirts, neckties and suits |

| Services | bespoke and ready-to-wear |

| Website | www.charvet.com |

Coordinates: 48°52′5.42″N 2°19′48.98″E / 48.8681722°N 2.3302722°E Charvet Place Vendôme, pronounced [ʃaʁvɛ plas vɑ̃dɔm], or simply Charvet, is a French high-end shirt maker and tailor located at 28 Place Vendôme in Paris. It designs, produces and sells bespoke and ready-to-wear shirts, neckties, blouses, pyjamas and suits, in the Paris store and internationally through luxury retailers.

The world's first ever shirt shop, Charvet was founded in 1838. Since the 19th century, it has supplied bespoke shirts and haberdashery to kings, princes and heads of state. It has acquired an international reputation for the high quality of its products, the level of its service and the wide range of its designs and colors. Thanks to the renown of its ties, charvet has become a generic name for a certain type of silk fabric used for ties.

Its exceptionally long history is associated with many famous customers, some of them infatuated with the brand. Also, writers have often expressed their characters' identity through references to Charvet.

History

Foundation

The store was founded in 1836 or in 1838[n. 1] by Joseph-Christophe Charvet,[4] known as Christofle[1] Charvet (1809–1870).[4][5]

His father Jean-Pierre, native of Strasbourg,[6] had been "curator of the wardrobe" for Napoleon Bonaparte,[7][8] a position created at the beginning of the Empire. The curator assisted the chamberlain or "master of the wardrobe", who supervised all aspects of the emperor's wardrobe – updating the inventories, placing orders, paying bills, and establishing regulations. This position was initially held, between 1804 and 1811 by count Augustin de Rémusat. When it appeared in 1811 Rémusat was mismanaging the wardrobe,[6] an inventory was requested to Jean-Pierre Charvet, and Rémusat was replaced by count Henri de Turenne d'Aynac.[9] Christofle's uncle, Étienne Charvet, was the steward of the château de Malmaison and later of the château de Saint Cloud.[6] Étienne Charvet's daughter Louise Caroline Catherine (1791–1861),[10] Christofle's first cousin, married at the age of 14 Constant, Napoleon's head valet. The marriage was arranged by Napoleon himself, who signed the marriage contract.[6] She became in 1813 a linen keeper at the château de Saint Cloud, therefore responsible for making the imperial shirts.[6] Her portrait (Figure, right) was bequested to the Malmaison museum in 1929 by Édouard Charvet.[11] Constant and his wife Louise did not to follow Napoleon in his exile to Elba, an "enormous mistake" according to Christofle's father.[6] Instead, they moved to Elbeuf and invested in a weaving factory, created by Louise's brother Jean-Pierre[6] and specialized in novelty fabrics for pants and lady coats.[12]

Christofle Charvet created the first shirtmaker store in Paris, for which the new term chemisier (shirtmaker) was coined.[13][n. 2] Previously, shirts were generally made by linen keepers with fabric provided by the customer,[15] but in this store of a new kind, clients were measured, fabric selected and shirts made on site.[16] The development of this specialty[17] trade was favored by a change in men's fashion, with more importance given to the waistcoat and the shirt collar,[18] which called for more propositions for the shirt front and a technical change. Previously, shirts were cut by linen keepers entirely of rectangles and squares. There were no shaping seams and no need for shirt patterns. The new interest for a closer fitting shirt led to curving the armhole and neckline or adding a shoulder yoke,[19] by application to the shirt of tailoring techniques. The new kind of shirt was called chemise à pièce (yoked shirt).[20] Alan Flusser credits Christofle Charvet with the original design of a collar that could be turned down or folded, much in the manner of contemporary collars,[21] and the concept of the detachable collar.[22]

In 1839, Charvet already had some imitators,[n. 3] but still the "best supply".[24] The same year, Charvet held the title of official shirtmaker to the Jockey Club,[16] a very exclusive Parisian circle, then headed by prince Napoléon Joseph Ney and inspired by count Alfred d'Orsay, a famous French dandy.[25] It had about 250 members, mostly aristocrats, who, despite the name of their club, were more interested in elegance than horses. Being a member was a necessary step in order to become a lion, the term used then for a dandy.[26] In an advertisement of March 1839, Charvet, presenting himself as the Club's shirtmaker, claimed to offer "elegance, perfection, moderate prices".[27] Soon after, the claim to moderate prices was dropped (see images, right).[28]

Joseph-Édouard Charvet, known as Édouard Charvet, (1842–1928)[29] succeeded his father Christofle in 1868.[1] He in turn was joined in the early 20th century by his three sons, Étienne, Raymond and Paul.[30]

Location

The store was initially located on the rue de Richelieu, at n° 103[31] and later at n° 93.[32]

It moved to n° 25, place Vendôme in 1877.[33][34] This move reflected a shift in the center of the Parisian high society[35] and the growing importance for fashion of both rue de la Paix, where the house of Worth had opened in 1858, and the palais Garnier against the Théâtre Italien, closer to Charvet's original location.[26] Though Charvet began to offer women's blouses and men's suits in its new store, men's shirts remained the house's specialty. An American journalist, visiting the store in 1909, reported "there were shirts of every variety and almost every color [,] artistic enough to make one long for them all, and each and every one most beautifully made."[36] The store was noted for its displays, compared in 1906 to Loie Fuller performances,[37] and Charvet paid an "immense salary" to the window decorator, who displayed "each day a new series", producing "veritable works of art in his harmonious combinations of scarves and handkerchiefs and hosiery".[38]

In 1921,[40][41] the store moved to n° 8, place Vendôme.

In 1982, it moved to its current location, at n° 28.[42]

Charvet remains the oldest shop on place Vendôme, which explains both the inclusion of the location into the firm's name, and the use as a logo[43][44] of the sun device, designed by Jules Hardouin-Mansart to ornate the handrails of the balconies of the Place, which was built in honor of Louis XIV, the Sun King.[39]

International recognition

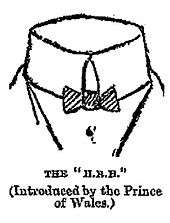

In 1855 Charvet exhibited shirts and drawers at the Paris World's fair.[32] The jury noted that Parisian shirt makers had an "unquestionable supremacy".[45][n. 4] Again, at the next Paris World's fair, Charvet exhibited shirts, drawers, vests and handkerchieves[48] and the Jury noted luxury shirts were a Parisian "monopoly".[49] When the king-to-be Edward VII visited the fair, he ordered Parisian shirts, as many other foreign visitors did,[50] and remained a loyal customer of Charvet, "honoring him during forty years with a special kindness"[51] (See List of Charvet customers). Charvet created[52] for the prince of Wales a certain style of shirt collar, the stand-up turn-down collar, also referred to as the H.R.H. collar, which became very popular at the end of the 19th century (Figure, right).[53]

In 1863, Charvet was considered[54] the first producer of fine shirts in Paris, claiming superiority "for taste and for elegance" on cuffs, bib and fit. Charvet's store was a "very important" destination for English visitors in Paris.[54] In the following years, Charvet developed its specialization in royal trousseaux. In 1878, he won a silver medal at the World Fair and a gold medal at the 1889 Paris World's fair, for which the Eiffel tower was built.[55] When it won the latter, the jury noted: "Fine shirts remain the property and glory of Paris. To be convinced of it, it is sufficient to give a look to the displays of the companies specialized in royal haberdashery".[49] Other royal patrons confirmed this princely speciality of Charvet, such as Alfonso XII of Spain (1878), Antoine, duke of Montpensier (1879), Philippe, comte de Paris (1893), and sultan Abdul Hamid II (See List of Charvet customers).

The clientele of Charvet also included artists such as Charles Baudelaire,[56] who gave a metaphysical dimension to dandyism,[57] George Sand,[15] whose lover Alfred de Musset never succeeded to become a member of the Jockey Club,[26] Édouard Manet,[58] nicknamed the "dandy of painting"[59] or Jacques Offenbach,[16] composer of La Vie Parisienne. In 1893, when he tried to enter the Académie française,[60] Verlaine had himself photographed wearing a "very beautiful Charvet scarf" (Figure, left).[61] Allegedly, a gift of 100,000 francs to "the greatest poet of our time, Verlaine", was the stake of a bet between Edmond de Polignac and Robert de Montesquiou. Having lost the bet, Montesquiou "naturally kept the 100,000 francs but gave Verlaine a very beautiful scarf". Upon hearing the story, Polignac cut all relations with Montesquiou.[60][61] Nevertheless, some other writers consider this story as a legend circulated by Montesquiou himself, as no document establishes the existence of this bet and Montesquiou was almost the only one in the elegant and cultured world to care for Verlaine.[62]

In 1894, an administrative report praised Charvet for constantly seeking high-novelty and setting the trend for other Parisian shirtmakers, having irreproachable manufacturing standards, and successfully enticing French factories to produce the raw materials traditionally supplied by England.[63]

After his 1897 portrait by Giovanni Boldini, Montesquiou's dandyism became famous and made him a frequent subject of caricatures.[64] In 1903, a French satirical magazine illustrated by a caricature from Sem to which Marcel Proust alluded in a letter to Montesquiou,[65] had Montesquiou saying: "Nobody in the world ever saw such things! Pinks, blues, lilacs, in silk, and in cobweb! Charvet is the greatest artist in the Creation."[64] In a letter to Montesquiou, alludes to the caricature by Sem of Montesquiou examining products at Charvet (Figure, right).

In 1905, Charvet, then also established in London, at 45 New Bond St,[36] and “rumored” to be contemplating an establishment in New York,[66] was considered the "foremost haberdashery of Paris and London".[66] Its customers included not only royalty, such as Alfonso XIII of Spain (warrant granted in 1913); Edward VIII, duke of Windsor; the French president Paul Deschanel, noted for his elegant Charvet cravats;[67] but also members of the high society gravitating around dandies such as Robert de Montesquiou and Evander Berry Wall, or artists as Jean Cocteau, who called Charvet "magic"[68] and wrote that it is "where the rainbow finds ideas",[69] and his friend Sergei Diaghilev.[70] According to Proust, whose shirts, ties and waistcoats were from Charvet, maybe by imitation of Montesquiou,[71] the latter was "the sign of a certain world, of a certain elegance".[72][n. 5] Proust also spent long moments at Charvet in search of a perfect tone for his cravats, such as a "creamy pink".[75] His tank tops (marcel in French) also came from Charvet.[76] In his Remembrance of Things Past (1919), Marcel, the narrator, waiting for the appointed hour of his lunch engagement at Swann's house, whiles away his time "tightening from time to time the knot of [his] magnificent Charvet tie".[77] In 1908, Charvet won a Grand Prix at the London Exhibition.[55]

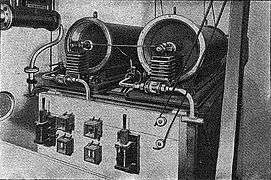

In 1901, Charvet opened a laundry at 3, rue des Capucines, next to his store, considered by some to be the first established in Paris,[79] a fact which later led some others to assume Charvet's laundry business had predated shirtmaking.[80] It was advertised as applying Pasteur's and Grancher's principles.[81][82] In 1903, Charvet moved his "model laundry",[83] to the place du Marché Saint Honoré, on premises belonging to the city of Paris, which specially authorized him in view of an innovative ozone-based process,[84] then licensed to the Parisian hospitals.[85] The soiled clothes, picked up at the customer's house by “special cars”,[86] were disinfected and bleached with ozone, then placed in a revolving drum worked by electricity[87] and soaked in a diastatic solution, in order to remove the starch and make the linen whiter, subsequently washed in soap and water, afterwards in a solution of ammonia to remove the soap, then whitened, starched, calendered and hand ironed.[88] The process was considered a model both for the quality of the output[89] and for the care taken of the health of the workers.[90] A "surprising" amount of laundry was sent over by British customers.[83] Like many other foreign customers,[91] William Stewart Halsted[92][93] and William H. Welch[94] regularly sent their shirts to be laundered to Charvet in Paris.[n. 6] Promotional stamps were produced for this laundry business and became collectible.[78] In 1906, a branch of the laundry was opened at 1, rue du Colisée, near the Champs-Élysées.[96] During World War I, Charvet significantly reduced the price of its laundry services to keep sufficient work for all his employees.[97] Towards the end of the war, the shortage of coal severely hit Charvet's laundry activity.[98] The "model laundry" of place du marché Saint Honoré was discontinued in 1933 when the place was restructured.[99]

- Views of the Charvet model laundries

Photo (1901). Separate soaping and soaking at the 1st model laundry, rue des Capucines.

Photo (1901). Separate soaping and soaking at the 1st model laundry, rue des Capucines. Photo (1901). Checking and sorting at the 1st model laundry.

Photo (1901). Checking and sorting at the 1st model laundry. Photo (1903). Ozone generators in the 2nd model laundry, place du Marché Saint Honoré

Photo (1903). Ozone generators in the 2nd model laundry, place du Marché Saint Honoré Mechanical washing machines in the 2nd model laundry.

Mechanical washing machines in the 2nd model laundry.

Charvet shirts were imported into the United States as early as 1853 (See figure right).[100] By 1860, Charvet's shirts turnover was equally divided between luxury bespoke shirts sold in the Paris store and ready made shirts for export, particularly to Russia, Great-Britain and Havana.[101] Also, following the custom of the time, designs and models were sold to American stores, to be locally reproduced.[102][103] In the 1920s, Charvet's name was associated in the United States with linen fabrics in "startingly floreated" patterns, used for shirt bibs and cuffs.[104] Nevertheless, into the middle of the 20th century, Charvet was selling only bespoke shirts in the Paris store.[n. 7]

In 1908, Charvet was the first European company to import American suits hand tailored in Chicago.[106][107]

The name Charvet was so well known that it became associated[108] with a certain silk fabric for ties (See Charvet (fabric)). Charvet's notability also extended to other items of clothing, such as shirts,[n. 8] shirtings,[n. 9] ties, gloves,[113] dress suits,[n. 10] waistcoats (see image, left),[n. 11][n. 12] undergarments,[n. 13] pocketchieves,[119] and women's waistbands[120] or shirtwaists[121] (See figures left), worn with special models of ties for ladies, such as one called le juge modeled after a judge's lappets.[122] The Chicago Tribune reported in 1909 that Charvet was showing "scarf pins that match in color any scarf that may be bought and some have the same designs carried out in them done in enamel. There are also waistcoasts buttons to be worn with certain ties and there are sets of these, cufflinks, and pins, all of which exactly match".[123] Charvet also supplied silk bed-sheets in colours such as black, green, mauve or violet.[124]

In the early 20th century, Charvet launched a toilet water, in a rectangular beveled bottle. One of the customers for this perfume was Boy Capel, Coco Chanel's lover. In 1921, two years after his accidental death, the flacon of Chanel's famous Nº 5 perfume was produced in the image of the Charvet bottle.[125]

Like many European companies, Charvet was greatly affected by World War I: "our looms have been destroyed, our collections pillaged, our printing blocks burned". Nevertheless, it continued to send representatives to the United States to show collections of novelties.[126]

- Views of corsages, chemisettes and shirtwaists 1896 - 1898

Sketch (1898) of a dress with chemisette and cravat

Sketch (1898) of a dress with chemisette and cravat

Sketch (1898) of a shirtwaist in batiste

Sketch (1898) of a shirtwaist in batiste Sketch (1898) of a shirtwaist in linon

Sketch (1898) of a shirtwaist in linon

Art Deco period

After 1912, with the development of the Art Deco style, Charvet, along with fashion designer Paul Poiret, started to commission art work from the French painter Raoul Dufy,[127] the "granddaddy of modem chic",[128] through the French weaver Bianchini-Férier.[129] Some of the first were related to the war, such as Les Alliés or the Victory Rooster (Figure, left).[130] This was followed by more silk squares, woven silk fabrics for vests,[25] and printed ramie fabrics for dressing gowns and shirts.[131] Some famous customers of the period were fashion designer Coco Chanel[132][n. 14] and the Maharadjah of Patiala who once placed a single order of 86 dozen shirts.[134]

In the late 1920s, Charvet was considered to produce "the finest cravats in the world",[135] with either conservative designs or “decidedly original”[136] patterns, such as postage-stamps[137][138] (See below) or much more “modernist”[139] patterns. At an exhibition called "L'art de la soie" held at the Musée Galliera in Paris in 1927, Charvet presented dressing gowns and neckties in matching patterns,[140] together with pyjamas,[141] shirts and handherchieves.[142] The company developed a practice of sending merchandises to its customers for approval, allowing them to select some or none and return the rest, subsequently referred to as the Charvet method.[143] It conceived a range of free-form[144] bold printed tie patterns which gained wide popularity in the USA.[n. 15] "Its chic was in their unfussy, nonchalant bearing. To the delight of their many admirers, the Charvets' open settings facilitated blending with all kind of fancy suits [...] The original Charvet prints became the first, and regrettably almost the last, bold figured necktie to symbolize upper-class taste".[148] Some such bold Charvet Art Deco ties which had belonged to John Ringling are on display at the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art.[149] These patterns, for which charvet became a generic name,[150][151] "foreshadowed"[152] the colorful designs which became popular after the war.[153] The company also produced beach linen robes with patterns up to two feet in diameter.[154]

In the 1930s, some window displays were made by painters as André Derain or Maurice de Vlaminck.[155]

Colban's takeover

When in 1965 the Charvet heirs sought to sell the firm, they were contacted by an American buyer. The French government, knowing Charvet had been for a long time General de Gaulle's shirtmaker,[n. 16] grew concerned. The French Ministry of Industry instructed Denis Colban, Charvet's main supplier, to locate a French buyer. Rather than approaching investors he decided to purchase the company himself.[132]

Until then, Charvet was operated in much the same way as it had been since its foundation: a customer was shown only what he requested, in most cases something fairly conservative. After Mr. Colban bought the firm, things changed. The change started when Baron Rothschild came into the store and asked to see some shirting fabrics, one of which was pink. When M. Colban, following previous Charvet practice, advised against the color, the Baron retorted, "If not for me, who is it for?" Some time later, Nelson Rockefeller requested some shirt swatches be sent to New York. Bold stripes and unusual colors were sent and eventually selected. Colban had changed Charvet's policies as well as its role in the design process with the customer.[158] A wide range of products was put on display, transforming the store in a "veritable casbah"[21] of colors and "almost edible"[159] fabrics. Colban also brought significant changes to the aspect of the store, having all the venerable furniture varnished in black.[21] He created new lines of products and started ready-to-wear finely made shirts for men[134] and women.[160] A few years after, he was one of the first of many famous European shops and designers to sell ready-to-wear shirts, ties and accessories to Bergdorf Goodman.[161][162] However, even while developing these new pre-made lines of products, Colban always insisted on the bespoke aspect of the firm as its core identity. He emphasised that "the essential hardest of all to accomplish in today's world of quick and easy pseudo solutions, is an atmosphere of 'yes' to the customer and, even more, a respect for that commitment",[163] re-iterating the focus of Charvet on its bespoke business.

Colban refused numerous offers to sell the company, maintaining the single store in Paris and continuing the house as a family business.[164] After his death in 1994,[165] the company has been managed by his two children, Anne-Marie and Jean-Claude.

Modern customers include French presidents François Mitterrand[166] and Jacques Chirac,[167] American presidents John F. Kennedy[n. 17] and Ronald Reagan,[15] French actors Catherine Deneuve[15] and Philippe Noiret,[170] American movie stars Sofia Coppola[171] and Bruce Willis,[172] fashion designers Yves Saint Laurent[173] and Jasper Conran[174] (See also: List of Charvet customers.).

Charvet today

Of the five most prominent French shirtmakers of the 20th century—Bouvin, Charvet, Poirier, Seelio, and Seymous—all but Charvet have closed their doors.[42] It is also the only remaining shirtmaker on Place Vendôme.[34]

The goal[175] of the company is to give its customers the option to custom order or customize everything[42][176] it sells, from neckwear[177] (including bow ties[178]) to underwear,[179] with "the idea that a garment that carries a personal stamp exceeds any other form of luxury".[180] Bolts of fabric on display throughout the store can be held against oneself to see how they really look.[181] Charvet creates exclusive fabrics for all its collections[182] and prides itself of going a long way to satisfy customers, remaking on request ties purchased years earlier[183] or changing a shirt's frayed collar and cuffs.[184]

Store

The store is located in one of the hôtels particuliers of Place Vendôme, Number 28. This building has a three-story Jules Hardouin Mansart facade, behind which Charvet occupies seven floors,[185] each owner on the Place having built to his own needs. This is the only store directly operated by Charvet. It is open from 10:00 am to 7:00 pm, Monday through Saturday.[186]

Per Denis Colban's merchandising ideas, the ground floor offers a contrast between the formality of the setting and the seemingly informal abundance[163] of silk accessories, from ties to scarves[187] to the "signature"[188] silk passementerie-knot cufflinks invented here.[n. 18] Each necktie comes in at least two dozen colorways and new designs arrive each week.[25]

Ready-to-wear shirts and at-home clothing are displayed on the fourth floor, ready-to-wear blouses on the second floor, and children's shirts on the first floor, but the third floor is dedicated to bespoke shirtmaking. This "centre of the universe for shirt aficionados"[194] could be the largest selection of fine shirtings in the world,[195] with over 6,000 different fabrics,[196] including a "legendary" Mur des Blancs (Wall of Whites)[197] of four hundred different white fabrics in 104 shades of white[198] and another of two hundred solid blues.[173] Customers can "debate not just the shade of white, not just the choice of cuff, not just the angle, depth and proportion of the collar, but also the infinitesimal differences in the weight of the interlining in collar and cuff and how this can and should be varied between formal, semi-formal and casual shirts".[199] The richly colored and unique"[200] fabrics are presented in full bolts, not on swatch cards.[42] Most of them are designed in-house by Charvet, for its own exclusive use[201] and woven from specially chosen gossypium barbadense[13] cotton from the Nile delta.[202] About a thousand new patterns are introduced each year,[203] all of them registered.[201] The Charvet stripes are often multicolored, asymmetric,[204] thinner than English stripes, softer and subtler in the matching of shades.[201][205]

Men's custom tailoring is on the sixth floor, which has the atmosphere of a men's club.[163] Some 4,500 bolts of fabric are on display there,[181] and the walls are hung with 1960s' fashion illustrations of Dean Martin look-alikes drawn by Jean Choiselat.[25]

- Views of the Place Vendôme store

Shop window

Shop window First floor

First floor Third floor

Third floor Fourth floor

Fourth floor Sixth floor

Sixth floor

Products

Shirts

The "unique"[42] care for precision and symmetry[206] expresses French classicism[207][n. 19] and is, according to Marie-Claude Siccard, a paradigm of the care for quality in luxury products.[209] In particular, a lot of attention is given to the regularity of stitches and the matching of patterns.[210] On a typical striped ready-to-wear shirt and unlike most other makes,[211] the placket is matched with the front,[205] the face of the collar with the bottom, the collar stripes line up with the yoke stripes, the yoke stripes with the sleeve stripes, the sleeve stripes with the sleeve placket stripes, and finally the shade of yarn used for the buttonholes is matched to the stripe,[212] the whole process creating the feeling the shirt is all one piece.[207] The yoke is one-piece and curved to follow the back. The left cuff is made one-quarter inch longer than the right to allow for the watch. The allowance is lower for made-to-order shirts. The cuff is made more or less wide, depending if the customer wants his watch to remain hidden under the cuff or to show. According to a Charvet representative, many customers have two different types of shirts: those for evening wear, intended to be worn with a flat watch, and the others for day wear, with a thicker watch.[213] For men, shirt tails are square and vented for a clean look. For women, they are rounded, with a signature side-seam gusset.[211] The collar is very clean-cut,[214] made from six layers of unfused cloth for a dressy, yet not stiff, appearance.[42] Instead, a free floating stiffener aims to provide more comfort and a better shape.[215] The stitching on a standard collar is four millimeters from the edge.[134] The stitching of the top and the edges are precise and well-planned.[211] The shirts are stitched with twin rows of single-needle tailoring, sewn one row at a time for minimum puckering and maximum fit.[216] There are twenty stitches per inch.[217] Buttons are made from Australian mother-of-pearl, cut from the surface of the oyster shell for added strength and greater color clarity.[42][218] For formal shirts, bibs are hand pleated.[219] Though its traditional ready-to-wear shirts are trim, the company has also introduced in 2009 a "slim fit" line.[220]

The care involved in the process of making a bespoke shirt is, according to Lara Marlowe, an expression of French perfectionism.[221] It requires a minimum of 28 measurements and an initial version made in basic cotton.[222] The fit is "full and snug at the same time".[223] The minimum order is one shirt.[224] There are only fifty shirt-makers working in the Saint-Gaultier atelier and only one person works on a shirt at a time, whether custom or ready-to-wear,[n. 20]doing everything except for the buttonholes and pressing the shirt.[208] Each shirt takes thirty days to complete.[225]

- Charvet shirt's pattern matching

Collar top and bottom.

Collar top and bottom. Cuff top and bottom.

Cuff top and bottom. Sleeve and yoke.

Sleeve and yoke. Sleeve and placket.

Sleeve and placket.

Pyjamas

The jacket is made of 14 pieces and the pants of 5.[226] As for the shirts, patterns are matched throughout; depending on the pattern complexity, the production time is between 7 and 9 hours.[226] Charvet pyjamas are, according to François Simon, a cult object.[226][n. 21]

Neckwear

Charvet ties, ranked as the best designer's ties in the USA,[229] are handmade,[230] generally from a thick multicolor brocade silk,[231] of a high yarn count,[202] often enhanced by the addition of a hidden color,[232] producing a dense[233] fabric which goes through a proprietary finishing to acquire lustre, fluidity and resilience[210] and achieve the right knot.[202] The company develops its own exclusive patterns and colors. It creates about 8,000 models per year,[234] Jacquard woven on exclusive commission, with silk either alone or mixed with other precious yarns, such as cashmere,[235] camel hair, bamboo yarn or covered with laminated precious metals, such as silver, gold or platinum,[236][237] with techniques dating back to the 14th century when the popes were based in Avignon,[238][n. 22] which were also used in the 1920s for vests.[237] Further to a long history of brocade patterns, first used in the 19th century for vests and then for ties,[238] Charvet offers, according to Bernard Roetzel, the largest range of woven silk neckties in the world.[240] The ties collection, sometime "unmistakably bold"[202] or "witty [and] wicked",[241] often noted for its shimmer and changing colors (Charvet ties' shimmer "has become so synonymous with the company that we call it the Charvet effect", says a retailer.[42]), uses about 5,000 shades[238] in over 100,000 combinations.[238][242]

Ties are made from three pieces of silk material cut at a 45-degree angle.[177] They are sewn entirely by hand[195] before being hand folded into shape.[177] Sevenfold ties are available on order.[234] Until the 1960s, nearly all Charvet ties were sevenfold. The company then decided an interlining could bring an improvement, helping protect the shape despite the pulling, and designed a proprietary interlining "which helps the silk keep its resilience and spring, but is not an obstruction when you tie a knot".[210]

The company produced a range of political ties for the 2008 American presidential campaign.[243][n. 23]

During the 1950s, it invented a special style of bow tie, a cross between a batwing and a butterfly, for the Duke of Windsor,[15] now referred to as the "Charvet cut".[246]

The eponymous style n° 30 of the book[247] on the 188 styles of tie knots[n. 24] is a three layered bow-tie worn by a woman, the constitutive ribbons being stitched together behind the neck.

Suits

Following the traditional bespoke process, measurements are taken, a basted canvas is built around the customer, then disassembled and traced onto paper, after which there are two more fittings. The suit is hand-sewn.[181]

Literary allusions and brand image

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Charvet Place Vendôme |

| “ | Sebastian entered – dove-grey flannel, white crêpe-de-Chine shirt, a Charvet tie, my tie as it happened, a pattern of postage stamps. | ” | |

| — Evelyn Waugh[137] | |||

References to Charvet in modern British or North American fiction illustrate the brand's identity: they help describe socially a character by its external appearance, such as elegance,[137] nobility,[249] wealth[250] or occupation.[251] Examples of Charvet's "brand emotion"[252] are literary allusions where the reference to the brand denotes a character's taste[253] or some of his psychological traits such as cheerfulness,[254] detachment,[255] eccentricity,[256] decadence[257] or mischief.[258]

Clients

For various reasons, some customers, such as Charles Haughey or Bernard-Henri Lévy, "became synonymous with Charvet".[259]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The founding year of Charvet is not a matter of consensus. For a majority of sources, it is 1838. Nevertheless, some other qualified sources[1][2][3] refer to 1836.

- ↑ The word chemisier is considered in 1845 as a neologism.[14]

- ↑ A British newspaper noted in 1840 that “a Shirt-making monomania has lately sprung up in Paris, and whoever will walk down the Rue Richelieu, and the Rue Neuve Vivienne, will see in gigantic letters, "Les Chemisiers de Paris," solely "consecrated" to that very useful article”.[23]

- ↑ All the other shirtmakers who established the then "unquestionable supremacy" of the Parisian shirt, Longueville, Durousseau, Darnet and Moreau Frères[46] went out of business before the end of the 19th century, leaving only Charvet to keep "the sparkle of its old fame which has never weakened and remains equal to itself".[47]

- ↑ On the other hand, Laurent Tailhade considered that "if we have to deal with oafs, bear my fondness for "bourgeois". Their ties come from Charvet"[73] and Paul Morand summed up the change of values at the start of the 20th century with the following question: "Why flaunt Charvet ties and have dirty feet?"[74]

- ↑ In his account of the imaginary correspondence between Pandit Motilal Nehru and a Parisian laundry in the year 1903, S.J. Perelman mused on the complications of such overseas dispatches and the implied "limitless wardrobe".[95]

- ↑ The beginning of Gilles, Drieu la Rochelle's major work, shows the eponymous hero told in 1917 by Charvet that he is not doing ready-to-wear shirts.[105]

- ↑ Charvet's prominent position[109] called for constant innovation, such as a "one thousand pleats" shirt for tuxedo wear, which actually counted 178 extremely fine tucks on each side.[110]

- ↑ At the start of the 20th century, an American advertisement called Charvet the "master-mind of French modes in shirtings".[111] "Charvet of Paris leads the Old World in the charm of the fabrics he has woven. We have his weaver working for us as well", boasted another one.[112]

- ↑ In 1909, for the Chicago Tribune, Charvet and Henry Poole & Co were "authorities" who "not only keep abraist of the times but may be called pioneers in the matters of fashions for men.[114]

- ↑ The French painter Maurice Lobre wrote in 1903 to Robert de Montesquiou that "Charvet wants to do marvels for you ... He is practising on me, making vests which are masterpieces from the back, the front, the top and the bottom.".[64]

- ↑ Charvet is credited with the invention of the straight waistcoat with a rolling shawl collar.[115] The company introduced pale gray waistcoats for evening wear and the black satin vest.[116] Its fancy waistcoats were first worn in the United States, towards the end of the 19th century, by Henry Clews and were afterwards also referred to as "Imandt Grand Prix" vests.[117]

- ↑ Henry Clay Frick's silk-and-wool undergarments bore ornate monograms and discreetly revealed the Parisian haberdasher's name in the weave of the fabric.[118]

- ↑ Chanel designed some costumes for Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. In 1928, she dressed the Muses in Balanchine's Apollon Musagète with a free adaptation of the antique tunic, whose pleats were bound with the silk of three Charvet ties.[133]

- ↑ This popularity even reached Al Capone,[145] Frank Costello[146] and Lucky Luciano.[147]

- ↑ All De Gaulle's shirts and ties came from Charvet. It was always his wife who bought them.[157]

- ↑ Kennedy wore linen handkerchieves from Charvet[168] and had the labels of his Charvet shirts removed,[42] in order to avoid evocation of an upper-class attitude.[168] One of his Charvet made shirts is exhibited in the Checkpoint Charlie museum.[169]

- ↑ Before acquiring its fame[189][190] for the silk knots it introduced in 1904,[191] Charvet had developed in the 19th century jewel cufflinks with his neighbor, the jeweler Cartier, including, around 1860, the then "famous boutons hongrois".[192] At the end of the 20th century, Charvet also became "famous [for the] Charvet silk knot, but in 24-carat gold".[193]

- ↑ "Charvet is profoundly faithful to the soul of France" said Jean-Louis Dumas, a former CEO of Hermès.[208]

- ↑ Ready to wear shirts are made in the same place and with the same standards as bespoke. "We cannot ask people in the morning to work slow and then to work fast in the afternoon", says Jean-Claude Colban.[134]

- ↑ In James Neugass' Rain of Ashes (1947), the main character wants to be "buried in his monogrammed Charvet pyjamas".[227] Patrick Leigh Fermor, a British travel writer, took on his trips to the Andes "Charvet pyjamas and fourteen bottles of airport whiskey".[228]

- ↑ The Avignon Papacy is the origin of the introduction of silk weaving in France.[239]

- ↑ During the same campaign, the Republican party spent $150,000 on dressing Sarah Palin "for the part of vice-president",[244] part of which was used on Charvet ties for her husband Todd.[245]

- ↑ Despite its name, this book does not present an exhaustive list of all possible tie knots, which have been demonstrated to be only 85, but also refers to bow ties, scarves and squares.[248]

Sources

- 1 2 3 La ville lumière. Anecdotes et Documents historiques, ethnographiques, littéraires, artistiques, commerciaux et encyclopédiques (in French). Paris, 25, rue Louis-le-Grand. 1909. p. 99. OCLC 8579760. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

La maison Charvet a été fondée en 1836 par M. Christofle Charvet, auquel a succédé en 1868 son fils M. Édouard Charvet, qui est encore aujourd'hui le chef de la maison avec ses trois fils comme collaborateurs.

- ↑ "Principaux Secteurs Économiques: Couture et mode: Quelques dates". Quid (in French). Archived from the original on March 9, 2009. Retrieved June 8, 2009.

1836: Christophe Charvet fonde une maison de chemises sur mesure.

- ↑ Hanover, Jérôme (August 5, 2007). "Charvet, une chemise qui se hausse du col.". Madame Figaro (in French). Retrieved January 4, 2013.

En 1836, comme tous les artisans, Christophe Charvet se déplace chez le client pour proposer ses échantillons de tissus. Mais au bout de deux ans, à l‘époque où le dandysme fait rage, il réalise que si ce même client vient à lui, il peut lui offrir un choix bien plus grand. La première boutique de chemise naît en 1838, rue de Richelieu.

- 1 2 Annuaire des notables commerçants de la Ville de Paris (in French). Paris: Techener. 1867. p. 37. OCLC 472061877. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ↑ Gregory, Alexis (1997). Paris deluxe: Place vendôme. New York: Rizzoli. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-8478-2061-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Wairy, Louis Constant; Dernelle, Maurice (2000). Mémoires intimes de Napoléon Ier par Constant son valet de chambre (in French). 1. Paris: Mercure de France. pp. 521, 559, 20, 28. ISBN 978-2-7152-2213-7.

- ↑ Marchand, Louis-Joseph-Narcisse (1955). Mémoires de Marchand, premier valet de chambre et exécuteur testamentaire de l'empereur (in French). 1. Paris: Plon. p. 233.

L'emploi de "conservateur de la Garde-robe" avait été créé au début de l'Empire et d'après Frédéric Masson, confié à Charvet.

- ↑ Recueil des traités et accords de la France (in French). 2. Paris: Imprimerie nationale. 1864. p. 408. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- ↑ Zieseniss, Charles Otto; Le Bourhis, Katell (1989). The Age of Napoleon: costume from Revolution to Empire, 1789–1815. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-87099-570-5.

- ↑ Hubert, Nicole; Pougetoux, Alain (1989). Châteaux de Malmaison et de Bois Préau ; Musées napoléoniens de l'Ile d'Aix et de la Maison Bonaparte à Ajaccio: catalogue sommaire illustré des peintures et dessins (in French). Ministère de la culture, de la communication, du bicentenaire et des grands travaux, Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux. p. 52. ISBN 978-2-7118-2175-4.

- ↑ "Madame Constant, née Louise-Caroline-Catherine Charvet (1791–1861), femme du valet de chambre de Napoléon Ier" (in French). Réunion des musées nationaux. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- ↑ Exposition des produits de l'industrie française en 1839. Rapport du jury central (in French). 1. Paris: Librairie Bouchard-Huzard. 1839. p. 72. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- 1 2 Murphy, Robert (Spring–Summer 2010). "Shirt Tales". Man around Town.

- ↑ de Radonvilliers Richard, Jean Baptiste (1845). Enrichissement de la langue francaise:Dictionnaire de mots nouveaux (in French). Paris: Léautey. p. 61.

Chemisier, s. m., f. ère; marchand, fabricant de chemises.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gavenas, Mary Lisa (2008). Encyclopedia of Menswear. New York: Fairchild Publications. p. 86. ISBN 978-1-56367-465-5.

- 1 2 3 Vergani, Guido; Belli, Franco; Brigidani, Cristina (1999). Dizionario della moda (in Italian). Milano: Baldini & Castoldi. p. 152. ISBN 88-8089-585-0.

Christophe Charvet, nel 1838, apre in rue de Richelieu un negozio dove prende le misure, propone le stoffe. Nel retro, si tagliano e si cuciono le camicie. È il primo negozio del genere.

- ↑ Académie française (1842). Complément du Dictionnaire de l'Académie française (in French). Paris. p. xii.

- ↑ Ruppert, Jacques (1996). Le costume français (in French). Paris: Flammarion. pp. 257–258. ISBN 2-08-120789-3.

- ↑ Shep, R.L.; Cariou, Gail (1999). Shirts & Men's Haberdashery 1840s to 1920s. Mendocino: R.L. Shep. pp. 4–5. ISBN 0-914046-27-6.

- ↑ Longueville (1844). Les mystères de la chemise. Paris: Aubert. OCLC 466317944.

- 1 2 3 Flusser, Alan (October 1982). "The Shirt Maker". TWA Ambassador.

- ↑ Fairchild Melhado, Jill; Gallagher, Gerri (2002). Where to Wear:Paris. Where to Wear II/Global. p. 34. ISBN 978-0-9715446-4-2.

Charvet pioneered the concept of the detachable collar and the Charvet collar still has a reputation of being attractive with any number of jacket styles.

- ↑ Byerly, Thomas; John Timbs (1840). The Mirror of literature, amusement, and instruction. 35. p. 62.

- ↑ The Court magazine & monthly critic and lady's magazine, & museum of the belles lettres, music, fine arts, drama, fashions, &c (in French). 3. London: Dobbs & Co. 1839. p. 682. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

La maison [...] la mieux fournie en ce genre si important, aujourd'hui que les chemises sont l'objet d'une si excessive recherche [...] Tout ce qui sort de ses magasins est frappé au coin de l'élégance et de la richesse, et la préférence méritée que lui accorde la classe fashionable est un juste hommage rendu au talent et au bon goût.

- 1 2 3 4 Gavenas, Marilise (February 12, 2007). "On the Right Bank; at the Storied House of Charvet, Luxury comes in Superabundance.". DNR. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- 1 2 3 Martin-Fugier, Anne (1990). La vie élégante, ou, La formation du Tout-Paris, 1815–1848 (in French). Paris: Fayard. p. 335. ISBN 2-213-02501-0.

- ↑ "Annonce". La Presse (in French). March 10, 1839. p. 4. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ↑ "Annonce". La Presse (in French). May 6, 1839. p. 4. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ↑ "Deuil". Le Figaro (in French). January 22, 1928. p. 2. Retrieved June 7, 2010.

- ↑ "Souscription pour un fonds de secours immédiat aux veuves, aux enfants et aux mères des aviateurs militaires". Le Figaro (in French). March 25, 1912. p. 1. Retrieved May 28, 2010.

- ↑ Bottin, Sébastien (1839). Almanach-Bottin du commerce de Paris, des départemens de la France et des principales villes du monde (in French). Paris: Bureau de l'Almanach du commerce. p. 208. Retrieved May 3, 2011.

Charvet, brev. chemisier du Jockey-Club, maison spéciale pour chemises et mouchoirs de batiste, r. Richelieu, 103.

- 1 2 Rondot, Natalis (1855). Catalogue officiel: Exposition des produits de l'industrie de toutes les nations, 1855 (in French). Paris: E. Panis.

2193 Charvet (C.) à Paris, rue Richelieu, 93 – Chemises, caleçons, gilets de flanelle.

- ↑ "Petite Gazette". Le Figaro (in French). October 29, 1876. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- 1 2 Sarmant, Thierry; Luce Gaume (2003). La Place Vendôme: art, pouvoir et fortune (in French). Paris: Action artistique de la ville de Paris. p. 250. ISBN 978-2-913246-41-6.

- ↑ Perrot, Philippe (1996). Fashioning the Bourgeoisie: A History of Clothing in the Nineteenth Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press. p. 41. ISBN 0-691-00081-6.

- 1 2 "Paris Fashions shows Luxury in New Shirs for Men". Chicago Tribune. September 29, 1909. Retrieved May 22, 2009.

- ↑ Sem (October 20, 1906). "Les modes masculines". Je sais tout (in French). Retrieved September 14, 2011.

- ↑ "Shopping in Paris". The Sydney Morning Herald. September 20, 1905. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

- 1 2 Gady, Alexandre (2002). "La seconde place : l'architecture". In Sarmant, Thierry. La place Vendôme. Art, pouvoir, et fortune (in French). Paris: Action artististique de la ville de Paris. pp. 84–85. ISBN 2-913246-41-9.

Très luxueuse, cette grille dont le modèle a été scrupuleusement suivi est peinte en bleu et or, les couleurs royales, et son dessin s'organise autour d'un soleil louisquatorzien.

- ↑ "Entre nous". Le Figaro (in French). August 31, 1921. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- ↑ Vogely, Maxine Arnold (1981). A Proust Dictionary. Albany: Whitston Pub. Co. p. 144. ISBN 0-87875-205-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Kissel, William (December 2004). "Style: Paris Match". Robb Report. Retrieved October 13, 2008.

- ↑ "Date de la déclaration de renouvellement : 30 novembre 2006" (PDF). Bullein officiel de la propriété industrielle (in French). November 23, 2007. Retrieved January 5, 2013.

- ↑ "Charvet by Charvet Place Vendôme SA". Trademarkia. Retrieved January 3, 2013.

- ↑ Exposition universelle de 1855 : Rapports du jury mixte international (in French). 2. Paris: Imprimerie nationale. 1856. p. 500. Retrieved May 29, 2010.

- ↑ Tresca, Henri Édouard (1855). Visite à l'exposition universelle de Paris, en 1855. Paris: Hachette. p. 741. Retrieved May 29, 2010.

- ↑ Exposition universelle internationale de 1900 à Paris. Rapports du jury international Group XII, class 86 (in French). Paris: Imprimerie nationale. 1902. p. 605. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- ↑ Exposition universelle de 1867, Catalogue général (in French). I. Paris: E. Dentu. 1867. p. 72.

Charvet (C.) à Paris, rue Richelieu, 93 – Chemises, caleçons, gilets et mouchoirs.

- 1 2 Exposition universelle internationale de 1889 à Paris. Rapports du jury international. Groupe IV, class 35 (in French). Paris: Imprimerie nationale. 1890. pp. 329, 356. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- ↑ Exposition universelle internationale de 1878 à Paris. Rapports du jury international. Groupe IV, class 37 (in French). Paris: Imprimerie nationale. 1880. pp. 124, 167. Retrieved November 25, 2008.

- ↑ "Les décorés des expositions". Le Figaro (in French). May 26, 1910. Retrieved June 27, 2010.

L'un de ses plus fidèles clients a été S.M. regrettée le roi Édouard VII qui, pendant quarante ans, l'honora d'une bienveillance particulière

- ↑ "Try our "98'Curzons!" A few fashion hints for men". Otago Witness. November 3, 1898. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

It was actually the Prince of Wales who introduced this shape. He got them originally about eight years ago from a manufacturer called Charvet, in Paris.

- ↑ Levitt, Sarah (1991). Fashion in photographs 1880–1900. London: Batsford. p. 81. ISBN 0-7134-6120-9.

- 1 2 Bericht der volkswirtschaftlichen Commission der württembergischen Kammer der Abgeordneten über den preu︣isch-französischen Handelsvertrag und die in Zusammenhang damit abgeschlossenen internen Verträge (in German). 1863. p. 575. Retrieved December 9, 2010.

Die Arbeiterinnen des ersten Fabrikanten, Herrn Charvet, zu Paris, welcher die ausgezeichnetsten Waaren liefert, ... „Unsere Hemden" — sagten sie — „sind den ausländischen überlegen an Geschmack und Eleganz." Allein nicht nur der vordere Einsaß und die Manchetten, welche man sieht, sind eleganter, sondern das französische Hemd paßt – nach der Erklärung der Pariser Fabrikanten – auch viel besser an den Leib... Herr Charvet treibt einen sehr bedeutenden handel mit blosen vorderren einsässen fûr hemden (devants de chemise); „die Engländer" — sagte er — „kommen häufig nach Frankreich, um „Einkäufe davon zu machen."

- 1 2 "Notice signalétique". Base de données des dossiers des titulaires de l'Ordre de la Légion d'Honneur (in French). Retrieved September 12, 2011.

- ↑ Drake, Alicia (2001). A Shopper's Guide to Paris Fashion. Northampton: Interlink Pub. Group. p. 30. ISBN 1-56656-378-X.

- ↑ Baudelaire, Charles (1964). The Painter of Modern Life and other essays. London: Phaidon Press. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-7148-3365-1.

It is a kind of cult of the self[,] a kind of religion.

- ↑ Nowell, Iris (2004). Generation Deluxe: Consumerism and Philanthropy of the New Super-rich. Toronto: Dundurn Press. p. 137. ISBN 1-55002-503-1.

- ↑ Korner, Hans (1996). Dandy, Flaneur, Maler (in German). Munich: W. Fink. ISBN 3-7705-2931-6.

- 1 2 Bertrand, Antoine (1996). Les curiosités esthétiques de Robert de Montesquiou (in French). Geneva: Librairie Droz. p. 518. ISBN 978-2-600-00107-6.

Une photographie de 1893 [...] représente en effet Verlaine en candidat à l'Académie française, arborant une superbe écharpe avec le négligé qui sied

- 1 2 Kahan, Sylvia (2009). In Search of New Scales: Prince Edmond de Polignac, Octatonic Explorer. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-58046-305-8.

- ↑ Brunel, Pierre (2004). Paul Verlaine (in French). Paris: Presses Paris Sorbonne. p. 30. ISBN 978-2-84050-365-1.

Si aucun document ne fait état des cent mille francs ou de la destination qui leur fut assignée, les lettres de Verlaine attestent en revanche les secours que le gentilhomme lui fit parvenir

- ↑ Exposition internationale de Chicago en 1893. (in French). 26. Paris: Imprimerie nationale. 1894. p. 102. Retrieved August 19, 2010.

Elle fournit la plus belle clientèle française et étrangère. Toujours à l'affût de hautes nouveautés, cette maison va constamment de l'avant, donnant le ton à ses nombreux confrères parisiens. Sa fabrication, conduite de père en fils par les chefs distingués de la maison, est irréprochable en tous points ; et son chiffre d'affaires, pour un établissement vendant presque exclusivement au détail, est considérable. Il faut encore souligner ses efforts, couronnés de succès, pour faire produire aux fabriques françaises les matières premières fournies de tout temps par l'Angleterre

- 1 2 3 Munhall, Edgar (1995). Whistler and Montesquiou. The Butterfly and the Bat. Paris: Flammarion. pp. 142–145. ISBN 978-2-08-013577-3.

- ↑ Société des amis de Marcel Proust et des amis de Combray, ed. (1957). Bulletin de la Société des amis de Marcel Proust et des amis de Combray. 7 (in French). 11. Combray. p. 294.

- 1 2 Men's Wear. 18. 1905. pp. 50, 101–102.

- ↑ Morand, Paul (1931). 1900 A.D. New York: W. F. Payson.

- ↑ Steegmuller, Francis (1970). Cocteau, a biography. Boston, Mass.: Little, Brown and Company. p. 47.

- ↑ Cocteau, Jean (1912). La danse de Sophocle (in French). Paris: Mercure de France. p. 133.

Charvet où l'arc-en ciel prend ses idées.

- ↑ Spencer, Charles; Philip Dyer; Martin Battersby (1974). The World of Serge Diaghilev. Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing. p. 21. ISBN 0-8092-8305-0.

- ↑ Fretet, Jean (1946). L'aliénation poétique (in French). p. 222.

- ↑ Albaret, Céleste (2003). Monsieur Proust. New York: New York Review of Books. p. 286. ISBN 1-59017-059-8.

- ↑ Picq, Gillles (2001). Laurent Tailhade ou de la provocation considérée comme un art de vivre (in French). Maisonneuve & Larose. p. 506. ISBN 978-2-7068-1526-3.

S'il faut inéluctablement frayer avec des mufles, souffrez que j'aime autant les "bourgeois". Leurs cravates sortent de chez Charvet et leurs façons ne manquent pas de savoir-vivre.

- ↑ Morand, Paul (1931). 1900 [i.e. Mil neuf cent] (in French). Les Éditions de France. p. 67.

Pourquoi étaler des cravates de chez Charvet et avoir les pieds sales?

- ↑ Pierre-Quint, Léon (1925). Marcel Proust: sa vie, son œuvre (in French). Paris: Éditions du Sagittaire. p. 52.

Sous le col rabattu, il portait des cravates mal nouées ou de larges plastrons de soie de chez Charvet, d'un rose crémeux, dont il avait longuement cherché le ton.

- ↑ Clausel, Jean (2009). Le marcel de Proust (in French). Roma: Portaparole. pp. 72–73. ISBN 978-88-89421-72-7. Retrieved April 13, 2010.

Il pointa l’index sur la tranche où était écrit en grandes anglaises: ‘M. Proust’ (...) Il souleva le carton: une pile de trois ou quatre maillots de corps à bretelles, en mailles de soie.

- ↑ Proust, Marcel. A l'ombre des jeunes filles en fleur. 1.

…tout en resserrant de temps à autre le nœud d'une magnifique cravate de chez Charvet…

- 1 2 Bulletin de la société archéologique, historique et artistique (in French). 2. Paris: Lefebvre-Ducrocq. 1905. p. 552.

Les timbres Charvet, longs et étroits, figurant un monsieur en habit: « Je me fais blanchir chez Charvet », et une dame en robe de soirée : « Et moi aussi »

- ↑ McIntyre, O. O. (March 24, 1925). "A New Yorker in Paris". Rochester Evening Journal and Post Express. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

Not so many years ago France sent its laundry weekly across the channel to London. Very little laundry work was done in Paris. The first laundry was built by Charvet, a fashionable haberdasher

- ↑ "The Lion's Fight". The Miami News. October 8, 1936. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

Swank Englishmen years ago used to send their laundry across the channel to Paris. Out of this laundry business grew the famous haberdashery salon of Charvet in the Place Vendome. The first Charvet was a washer-man

- ↑ "Advertisement". Le Figaro (in French). October 26, 1901. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

- ↑ "Blanchisserie modèle de la Maison Charvet". L'Illustration (in French). May 25, 1901.

- 1 2 "La presse anglaise et les échos de la récente visite des blanchisseurs anglais à leurs confrères parisiens". Le Figaro (in French). September 28, 1906. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

Daily Telegraph: “Les délégués anglais ont admiré la perfection technique de la Blanchisserie modèle de la maison Charvet”. Daily News: “Les délégués ont été très surpris de la quantité de paniers de linge blanchi prêts à être expédiés en Angleterre qu'ils ont vus dans cette maison”.

- ↑ "A travers Paris". Le Figaro (in French). December 24, 1902. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- ↑ Otto, Marius (1903). "Les progrès récents réalisés dans l'industrie de l'ozone". Mémoires et compte rendu des travaux de la Société des ingénieurs civils (in French). Paris: Société des ingénieurs civils de France. 81: 567–569. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

Grâce à l'initiative courageuse d'un grand industriel parisien, M. Charvet, une blanchisserie modèle, à l'ozone, vient d'être installée au Marché Saint-Honoré. Le Conseil municipal de Paris a autorisé cette création dans les locaux appartenant à la Ville [...] Une licence des procédés employés par M. Charvet a été concédée aux établissements hospitaliers de la capitale. L'ozone est employé dans la blanchisserie Charvet, pour la désinfection et pour le blanchiment proprement dit.

- ↑ "Petites histoires". Le Figaro (in French). October 19, 1903. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- ↑ Oliver, Thomas (1908). Diseases of Occupation from the Legislative, Social, and Medical Points of View. Methuen & Co. p. 392.

- ↑ Wurtz, R.; Tanon, L. (1905). "Note au sujet du décret relatif aux précautions édictées pour la manipulation du linge sale dans le blanchissage du linge". Revue d'hygiène et de police sanitaire (in French). Paris. 27: 573. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

Au sortir du cuvier où il a été coulé, le linge est lavé, puis rincé à l'eau pure ou à l'eau additionnée d'eau de javelle, puis azuré ; enfin essoré, séché, empesé, repassé, cylindré.

- ↑ "A Model Parisian Laundry". Scientific American. 57 (1480): 23716. 1904.

- ↑ Oliver, Thomas (1908). Diseases of Occupation from the Legislative, Social, and Medical Points of View. Methuen & Co. p. 392. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

- ↑ Sitwell, Osbert (1972). Laughter in the Next Room. Greenwood Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-8371-6042-9.

When they went back to Russia, [the Grand Dukes] would send their linen from St. Petersburg right across Europe, to be washed at Charvet's, the famous shirt maker in Paris.

- ↑ Gross, Terry (February 22, 2010). "Re-Examining the Father of Modern Surgery". National Public Radio. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ↑ Imber, Gerald (2010). Genius on the Edge: The Bizarre Double Life of Dr. William Stewart Halsted. Kaplan Publishing. p. 250. ISBN 978-1-60714-627-8.

- ↑ Fleming, Donald (1954). William H. Welch and the Rise of Modern Medicine. New York: Little, Brown and Company. p. 88.

- ↑ Perelman, S. J. (February 12, 1955). "No starch in The Dhoti, S'il Vous Plait". The New Yorker. New York. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

- ↑ "La Blanchisserie modèle de la maison Charvet". Le Figaro (in French). May 15, 1906. Retrieved April 6, 2011.

Sur un simple coup de fil des voitures spéciales viennent prendre à domicile pour le rendre dans la huitaine le linge d'hommes et de dames

- ↑ "Renseignements utiles". Le Gaulois (in French). August 11, 1914. Retrieved May 3, 2011.

- ↑ "Laundry troubles". The West Australian. February 19, 1917. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

- ↑ "Vieux Paris". Le Figaro (in French). August 29, 1933. Retrieved April 9, 2011.

C'est cette blanchisserie qui disparaît présentement.

- ↑ "Perfumeries and Gentlemen's Furnishing Goods". Times-Picayune. March 29, 1853.

- ↑ Traité de commerce avec l'Angleterre: enquête (in French). Paris: Imprimerie Impériale. 1861. pp. 423–433. Retrieved April 10, 2011.

- ↑ "Advertisement". Detroit Free Press. March 27, 1898.

- ↑ "Making stock for charity". The Milwaukee Journal. September 22, 1897. p. 5. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

One young woman has sent over to Charvet, the swell shirt-maker of Paris, for some new patterns, and she intends selling hers, when copied.

- ↑ "For the well dressed man : Clothes for the Evening, for Weddings, and Other Formal Occasions". Vanity Fair. May 1920. p. 87. Retrieved October 15, 2012.

- ↑ Drieu la Rochelle, Pierre (1939). Gilles (in French). Paris: Gallimard. pp. 16–17.

"Nous n'avons pas de chemises toutes faites, monsieur", répondit M. Charvet lui-même.

- ↑ "Paris wears Chicago clothes". Chicago Tribune. March 26, 1908. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ↑ "Do you blame us for boasting". Mt. Sterling Advocate. June 2, 1909. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- ↑ "Business World" (PDF). New York Times. October 3, 1914. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

The full dress tie made of charvet material is a favorite at the present time and ties of this fabric can be purchased in white, pearl and black for dinner and evening wear.

- ↑ "Second Empire effects are seen" (PDF). New York Times. October 5, 1913. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

[Charvet] always has the last word on shirts.

- ↑ Men's Wear. 24. 1907. p. 51. Retrieved September 1, 2011.

- ↑ Beaunash (March 9, 1912). "Advertisement of John David". New York Times.(subscription required)

- ↑ "Men's Shirts to Order". New York Times (advertisement). January 24, 1900.(subscription required)

- ↑ Farmers' Loan and Trust Company. 1914. p. 13.

- ↑ "Again rumors of colored evening coats". Chicago Tribune. September 29, 1909.

- ↑ Praslières, Maurice (1903). "La mode masculine". Les Modes (in French) (31): 23. Retrieved March 7, 2010.

C'est Charvet qui a inventé le gilet à châle roulé et bouffant, droit, à un rang de boutons.

- ↑ "Sombre shades for men". Baltimore Sun. February 25, 1915. Retrieved July 3, 2011.

- ↑ de Lyon Nicholls, Charles Wilbur (1975). The ultra-fashionable peerage of America. Manchester: Ayer Publishing. p. 37. ISBN 978-0-405-06930-7.

- ↑ Jones Arbitman, Kahren; Kahren Hellerstedtand (1989). Clayton, the Pittsburgh home of Henry Clay Frick: art and furnishings. Pittsburgh: Frick Art & Historical Center. p. 61. ISBN 978-0-8229-6905-1.

- ↑ Forman, Justus Miles (1910). Bianca's Daughter. New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 135.

The pale tones of shirt and cravat and out-peeping pochette bespoke the genius of the well-known M. Charvet.

- ↑ "Advertisement". The Philadelphia Recorder. October 8, 1902. Retrieved April 20, 2011.

The Charvet waist of moire with the new stock has taken women by storm we are copying it by dozens in pale colored moires

- ↑ De Forest, Katharine (September 18, 1897). "Our Paris letter". Harper's Bazaar.

The news Charvet shirt-waist [...] will become standard so it is worthwhile describing again. The under part of the waist is cut bias, and adjusted to button in front, like a tight waist. The blouse part is put into the collar separately. It is nothing but two loose fronts laid in side pleats, and blousing into the belt independently of the under part

- ↑ De Forest, Katharine (July 1, 1902). "Recent happenings in Paris". Harper's Bazaar.

- ↑ "Man may go limit in handkerchiefs and ties". Chicago Tribune. September 29, 1909.

- ↑ de Waleffe, Maurice (October 1932). "Let us dress ourselves in silk". La Soierie de Lyon. Retrieved January 31, 2012.

- ↑ Bollon, Patrice (2002). Esprit d'époque: essai sur l'âme contemporaine et le conformisme naturel de nos sociétés (in French). Le Seuil. p. 57. ISBN 978-2-02-013367-8.

L'adaptation d'un flacon d'eau de toilette pour hommes datant de l'avant-guerre du chemisier Charvet.

- ↑ "Paris Offers Ecru Shirts". Boston Daily Globe. January 17, 1915.

- ↑ de Montmorin, Gabrielle (December 30, 2011). "Charvet, le royaume de la couleur". Le Point (in French). Retrieved April 23, 2012.

- ↑ "Slick Chic". Time Magazine. November 8, 1948. Retrieved November 24, 2008.

- ↑ Tourlonias, Anne (1998). Raoul Dufy, l'œuvre en soie (in French). Avignon: Barthelemy. p. 41. ISBN 2-87923-094-2.

Le 1er mars 1912, Raoul Dufy et Charles Bianchini signent le contrat.

- ↑ Raoul Dufy: Paintings, Drawings, Illustrated Books, Mural Decorations, Aubusson Tapestries, Fabric Designs and Fabrics for Bianchini-Férier, Paul Poiret Dresses, Ceramics, Posters, Theatre Designs. London: Arts Council of Great Britain. 1983. p. 106.

- ↑ Tuchscherer, Jean-Michel (1973). Raoul Dufy, créateur d'étoffes (in French). Mulhouse: Musée de l'impression sur étoffes. p. 22.

Ce tissu peu courant était fabriqué par un ami de Monsieur Bianchini et fourni en particulier à Charvet – chemisier place Vendôme – qui en faisait des chemises, robes de chambre, etc.

- 1 2 Chaille, François (1994). The book of ties. Paris: Flammarion. p. 119. ISBN 2-08-013568-6.

- ↑ Acocella, Joan Ross (1988). The Art of enchantment: Diaghilev's Ballets Russes, 1909–1929. Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. p. 94. ISBN 978-0-87663-761-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Patner, Josh (June 4, 2005). "What's my line". New York Times. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ↑ Reynolds, Bruce (1927). Paris with the lid lifted. G. Scully. p. 190.

- ↑ The New Yorker. F-R Pub. Corp. 1933. p. 72.

- 1 2 3 Waugh, Evelyn (1945). Brideshead Revisited. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. p. 31. ISBN 0-316-92634-5.

- ↑ Taylor, Elizabeth (1951). A Game of Hide and Seek. New York: Knopf. p. 117.

- ↑ Moseley, Seth H. (June 6, 1937). "Colorful Designs Are Featured in Braces, Garters". St Petersburg Times. Retrieved April 10, 2011.

Charvet patterns, named after the Parisian modernist who originated them, are derived in imitation of such natural objects as leaves and flowers, but look more like lightning hitting twice in the same place

- ↑ "Chronique de l'art décoratif". L'art vivant (in French). 1927. pp. 619–620.

Charvet [...] expose un patron complet : robes de chambre et cravates de belle qualité et aux heureux dessins, aux riches couleurs

- ↑ "L'art moderne de la soie". La Renaissance de l'art français et des industries de luxe. July 1927. p. 370. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

- ↑ "L'art de la soie au musée Galliera". L'Opinion (in French). 1927. pp. 39–40.

- ↑ Kanin, Garson (1967). Hollywood: stars and starlets, tycoons and flesh-peddlers, moviemakers and moneymakers, frauds and geniuses, hopefuls and has-beens, great lovers and sex symbols. New York: Viking Press. p. 270. OCLC 17794150.

Charvet will send over, say, a dozen neckties. You may choose one or two or none and return the rest

- ↑ 75 years of fashion. Fairchild Publications. 1965. p. 123. Retrieved September 2, 2011.

- ↑ Breslin, Jimmy (1991). Damon Runyon: A Life. Boston: Ticknor and Fields. p. 347. ISBN 0-89919-984-4.

- ↑ "Frank Costello's only Fear is Wife". The Miami News. May 5, 1947. p. 30. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ↑ Gosch, Martin A (1975). The last testament of Lucky Luciano. New York: Macmillan Publishers. p. 74. ISBN 0-333-17750-9.

- ↑ Flusser, Alan (2002). Dressing the Man. New York: HarperCollins. p. 156. ISBN 0-06-019144-9.

- ↑ "Other estate happenings". Sarasota Magazine. April 1, 2007. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- ↑ "Stylists Report Linen Shirts Are Favored for Men". St. Petersburg Times. April 25, 1937. Retrieved June 9, 2009.

- ↑ "Ties Will Show Bolder Trend in Colors, Lines". Washington Post. September 23, 1936.

The new trend in necktie fabrics shows a strong leaning towards bolder color combinations and designs, many of them inspired by the French school of modern design. Some houses report the importance of large charvet and school patterns, breaking away from the small neat patterns of past seasons.

- ↑ Gibbings, Sarah (1990). The Tie. Trends and Traditions. New York: Barron's. p. 100. ISBN 0-8120-6199-3.

- ↑ Ruttenberg, Edward (1948). The American male: his fashions and foibles. New York: Fairchild Publications. p. 329.

The former serviceman [...] is rolling around in color and sparking up as he considers the possibilities of Charvet patterns vs. the conservative. The thirst for variety, caused by long abstinence while bearing arms, fins expression in colorful cravats.

- ↑ Schoeffler, O.E.; William Gale (1973). Esquire's encyclopedia of 20th century men's fashions. McGraw-Hill. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-07-055480-1.

- ↑ "Littérature et publicité". Le Figaro (in French). April 26, 1932. Retrieved June 26, 2010.

Il est certes bien naturel que Vlaminck ou Derain composent des enseignes pour Charvet [...] On ne voit pas de raison qu'un étalage de chemisier ne fasse pas une aussi bonne nature morte que des langoustes ou des citrouilles.

- ↑ Labro, Philippe. Je connais des gens de toutes sortes (in French). Paris: Gallimard. p. 96.

Il n'a plus désormais comme uniforme que le costume ample et croisé (sombre), la cravate noire, la chemise blanche

- ↑ Tauriac, Michel (2008). Vivre avec de Gaulle: les derniers témoins racontent l'homme (in French). Paris: Plon. p. 396. ISBN 978-2-259-20721-8.

- ↑ Flusser, Alan (1981). Making the man. New York: Wallaby books. p. 190. ISBN 0-671-79147-8.

- ↑ Duka, John (December 26, 1983). "Shopping in London and Paris for Traditional Men's Clothes". New York Times.

- ↑ Sheppard, Eugenia (July 17, 1978). "Shirtmaker Designs Collection for Women". Toledo Blade. Retrieved June 9, 2009.

- ↑ Neimark, Ira (2006). Crossing Fifth Avenue to Bergdorf Goodman. New York: Specialist Press International. p. 163. ISBN 1-56171-208-6.

- ↑ Hochswender, Woody (May 10, 1988). "Patterns". New York Times. Retrieved June 3, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Harris, Leon (August 1987). "Paris Shirtmaker Extraordinaire". Town & Country.

- ↑ "Shirt tales". DNR. February 12, 2007.

The Colban family's textile expertise is embedded in the very soul of the store.

- ↑ "Denis Colban". Libération (in French). January 7, 1995. Retrieved May 22, 2009.

Denis Colban, président de Charvet, [...] est décédé le 28 décembre à l'âge de 74 ans à la suite d'un arrêt cardiaque.

- ↑ "Vente Mitterrand" (PDF) (in French). Retrieved October 3, 2008.

- ↑ Probst, Jean-François (2007). Chirac, mon ami de trente ans (in French). Paris: Denoël. ch. 6. ISBN 2-207-25824-6.

Il envoie le chauffeur lui acheter des boutons de manchettes ou ses chemises faites sur mesure chez Charvet

- 1 2 Lewis, Neil A. (January 19, 1997). "Presidential Chic, From Jabots To Polyester". New York Times. Retrieved May 7, 2009.

- ↑ Foulkes, Nick (October 23, 2009). "Checkpoint Charvet". Finch's Quarterly Review. Retrieved December 29, 2009.

- ↑ Noiret, Philippe (2007). Mémoire cavalière (in French). Paris: Laffont. p. 7. ISBN 2-221-10793-4.

- ↑ Hirschberg, Lynn (September 24, 2006). "Sofia Coppola's Paris". New York Times. Retrieved October 8, 2008.

- ↑ Körzdörfer, Norbert (June 18, 2007). "Ich umarme jeden Tag den Tod". Bild (in German). Retrieved October 21, 2008.

Er trägt einen grauen „Charvet“-Maßanzug (nur 1 Knopf wie JFK, aufgeknöpftes Maßhemd).

- 1 2 Soltes, Eileen (April 2007). "Get shirty". Portfolio. Retrieved October 1, 2008.

- ↑ "I'm typically male in my approach to clothes. I don't like waste. I like uniform; What's in the wardrobe of one of the UK's top fashion designers?". The Mail on Sunday. December 4, 2005.

- ↑ Seckler, Valerie. "Keeping a constant aim amid fashion's quick change" (PDF). WWD. Retrieved August 30, 2011.

Excellence, which he believes is emblematic of such brands as Chanel, Charvet, Apple and The Economist.

- ↑ Won, Nancy (October 29, 2010). "48 hours in Paris". Globe and Mail.

Everything is either custom-made or customizable, including ties and handkerchiefs.

- 1 2 3 "Charvet neckwear". Robb Report recommends. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- ↑ Максимова, Яна (December 2010). Полет бабочки. Departures (in Russian).

Сейчас это единственный Дом во Франции, предлагающий своим клиентам галстуки-бабочки по индивидуальной выкройке – sur mesure.

- ↑ Smiley, Tavis (June 18, 2003). "Interview: Andre Leon Talley discusses the fashion industry". NPR Tavis Smiley.

- ↑ Store director citation in: Foreman, Katya (July 3, 2007). "Catering to demanding customers with custom made". WWD.

- 1 2 3 Vandewalde, Mark (March 2007). "Style: Paris for Men Only". Departures Magazine. Retrieved October 30, 2008.

- ↑ Martin-Bernard, Frédéric (January 2005). "Charvet". L'Officiel Homme 2 (in French). Retrieved May 21, 2009.

Nous créons des tissus exclusifs pour toutes nos collections.

- ↑ Imran, Ahmed (February 19, 2008). "How to reach second base online". Financial Times. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

- ↑ Loyer, Michèle (March 16, 1996). "Luxury Companies Focus on Service". International Herald Tribune.

- ↑ Hesse, Georgia (1989). The Penguin guide to France. Penguin Books. p. 146. ISBN 978-0-14-019902-4.

- ↑ "Charvet Frommer's review". Frommer's. Retrieved May 8, 2009.

- ↑ Blanks, Tim (March 12, 2009). "Tim Blanks Finds Philosophy Via Charvet". Style.com. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- ↑ Donnally, Trish (March 18, 1992). "Crisp White Shirts A Fashion Must : They complement men's-wear styles.". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ "What new Autumn Blouses are like" (PDF). New York Times. September 20, 1908. Retrieved October 21, 2008.

Charvet [link] buttons of twisted braid are quite the style.

- ↑ Bachofen, Katrin (November 18, 2009). "Grosses Comeback der kleinen Knöpfe". Handelzeitung (in German).

Eine modische Alternative zu Manschettenknöpfen aus Edelmetall sind übrigens doppelte farbige Seidenknoten, die auf den Pariser Hemdenmacher Charvet zurückgehen und nach 1900 in Mode kamen.

- ↑ Corbett, Patrick (2002). Verdura: the life and work of a master jeweler. Harry N. Abrams. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-8109-3529-7.

- ↑ Nadelhoffer, Hans (2007). Cartier. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-8118-6099-4.

- ↑ Tryon, Thomas (1987). All that glitters. New York: Dell Publishing. p. 225. ISBN 978-0-440-10111-6.

- ↑ Davis, Charlote Williamson (2007). 101 Things to Buy Before You Die. London: New Holland Publishers. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-84537-885-1.

- 1 2 Boyer, Bruce (February 2002). "Charvet and the well-tailored man". Departures Magazine. Retrieved October 2, 2008.

- ↑ "Charvet shirts". Robb Report. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- ↑ Foulkes, Nicholas (December 26, 2010). "Wide-eyed boys witness the legendary Wall of Whites". Financial Times. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- ↑ Tang, David (September 16, 2011). "Panamas and paranoia". Financial Times. Retrieved September 17, 2011.

- ↑ Foulkes, Nick (January 31, 2009). "The Measure of a Man". Newsweek. Retrieved June 28, 2010.

- ↑ Gault, Henri; Millau, Christian (1982). THe Best of Paris. Crown Publishers & Knapp Press. p. 439. ISBN 978-0-517-54775-5.

- 1 2 3 Park, Paula (January 15, 2010). "A Shirt's Tale". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved January 15, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Cannon, Michael (January 2002). "Incomparably Charvet". Town & Country.

- ↑ Anaya, Josepha (April 2009). "Maison Charvet: L'Etoffe d'une Légende". Balthazar (in French).

Chaque année nous proposons environ mille nouvelles références.

- ↑ Brunel, Charlotte (October 8, 2004). "Obsession Les variations infinies de Charvet". Le Monde (in French). Retrieved October 29, 2010.

- 1 2 Foulkes, Nick (June 2003). "Luxury". GQ.

- ↑ "2009 Reader's Choice: First Picks". Robb Report. February 1, 2009. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

Each Charvet shirt is a study in symmetry

- 1 2 Walther, Gary (May 1999). "Shirt tales". Departures Magazine.

- 1 2 Flusser, Alan (1996). Style and the Man. New York: Harperstyle. p. 317. ISBN 0-06-270155-X.

- ↑ Sicard, Marie-Claude (2010). Luxe, mensonges et marketing (in French). Pearson Education France. p. 150. ISBN 978-2-7440-6456-2.

Dans le luxe on porte [à la qualité] une attention toute particulière et il faut en avoir fait l'expérience pour mesurer toute la distance qu'il peut y avoir entre une chemise sur mesure de chez Charvet et n'importe quelle chemise de confection courante, par exemple.

- 1 2 3 Koh, Wei (February–March 2009). "Shirt stories: a year in the life of a Charvet devotee" (Reprint). The Rake. Retrieved June 2, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Coffin, David Page (1993). Shirtmaking: Developing skills for fine sewing. Newton: The Taunton Press. p. 134. ISBN 1-56158-015-5.

- ↑ Foulkes, Nicholas (February 16, 2003). "Getting Shirty". The Mail on Sunday.

- ↑ Fromont, Valérie (March 25, 2009). "L'affaire du poignet". Le Temps (in French). Retrieved May 22, 2009.

«Les mesures se prennent toujours avec la montre, explique-t-on chez le chemisier Charvet. Nous faisons le poignet plus ou moins large, selon que la personne souhaite que sa montre retombe sur l'avant du poignet ou reste cachée à l'intérieur. Beaucoup de nos clients ont deux types de chemises: celles pour le soir, destinées à être portées avec une montre plate, et d'autres pour la journée, avec une montre plus grosse.» Dans cette maison parisienne, on calcule pour les chemises sur mesure une ampleur d'un centimètre entre la peau et le tissu. Mais dans le prêt-à-porter, cette ampleur est souvent plus large pour que les mesures puissent convenir à des poignets plus larges et à la taille inconnue d'une montre.

- ↑ Boyer, Bruce (Autumn 1995). "The Best Off-the-Rack Wardrobe". Cigar Aficionado. Retrieved December 3, 2008.

- ↑ "The perfect white shirt". Luxury Now. June 27, 2006. Retrieved October 4, 2008.

- ↑ Ong, Cat (August 3, 1997). "Show me the money". he Straits Times.

- ↑ Fairchild, Jill; Gerri Gallagher (2003). Where to Wear: Paris 2004. Where to Wear ll/Global. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-9720215-2-4.

- ↑ Boyer, Pascal. "Dans les coulisses de charvet incomparable institution" (in French). Dandy. Retrieved June 7, 2012.

- ↑ Van De Walle, Mark (November 2008). "Pure formality". Departures Magazine. Retrieved May 23, 2010.

- ↑ Koenig, Gillian (April 7, 2008). "Transatlantic Appeal". DNR.

- ↑ Marlowe, Lara (December 19, 2003). "Why I love living in Paris ; Lara Marlowe and her cat Spike adore living in Paris - the pinnacle of civilisation, she says (and Spike, if he could speak, would agree)". The Irish Times. Retrieved April 15, 2012. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Treacy, Karl (March 5, 2004). "A few upscale brands are proud to ignore the vagaries of seasonal fashion". International Herald Tribune.

- ↑ Hainey, Michael (December 2003). "A great White". Departures Magazine. Retrieved October 10, 2008.

- ↑ Capital (in German). 43. Köln: Capital Verlagsgesellschaft. 2004. p. 145.

Bei Nobel-Chemisier Charvet in Paris kann man [...] auch mit einem einzigen Hemd oder eine Bluse einfangen.

- ↑ Cannon, Michael (April 1, 2004). "The colors of Charvet". Town and Country. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Simon, François (August 18, 2010). "Le pyjama à rayures Charvet". Le Figaro (in French).

- ↑ Neugass, James (1947). Rain of Ashes. New York: Harper (publisher). p. 178.

- ↑ Brothers, Barbara; Gergits, Julia Marie (1999). British travel writers, 1940–1997. Detroit: Gales Group. p. 80. ISBN 0-7876-3098-5.

- ↑ Santelmann, Neal (May 26, 2004). "The finest neckties". Forbes. Retrieved October 1, 2008.

- ↑ Storey, Nicholas (2008). History of Men's Fashion: What the Well Dressed Man is Wearing. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 27. ISBN 978-1-84468-037-5.

- ↑ Colman, David (November 16, 1997). "The Details; Fabrics Fit to Be Ties". The New York Times. Retrieved November 2, 2008.

- ↑ "Charvet". Retrieved July 3, 2009.

- ↑ "Paris: Best Style Shops". Esquire. March 26, 2009. Retrieved May 21, 2009.

- 1 2 "Fondée à Naples en 1914 par Eugenio Marinella, la maison Marinella est actuellement dirigée par son petit-fils Maurizio qui dessine lui-même les motifs des soieries, toujours imprimées en Angleterre.". Bilan (in French). October 1, 2008.

Charvet, place Vendôme, produit 8000 modèles de cravates par an et réalise des sept plis sur mesure pour les clients les plus exigeants.

- ↑ "The Style Guide". Esquire. November 1, 2002. Retrieved May 6, 2009.

- ↑ Gallet, Hervé (March 2009). "Renouer avec la cravate".