Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin

| Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin | ||||||||||

| Herzogtum Mecklenburg-Schwerin | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

Mecklenburg-Schwerin | ||||||||||

| Capital | Schwerin | |||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | |||||||||

| Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin | ||||||||||

| • | 1701–1713 | Frederick William | ||||||||

| • | 1713–1728 | Karl Leopold | ||||||||

| • | 1728–1756 | Christian Ludwig II | ||||||||

| • | 1756–1785 | Frederick II | ||||||||

| • | 1785–1815 | Frederick Francis I | ||||||||

| History | ||||||||||

| • | Treaty of Hamburg | 1379 | ||||||||

| • | Raised to Grand Duchy | 1815 | ||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||

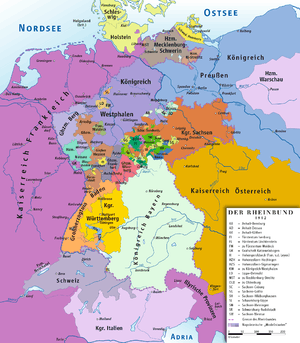

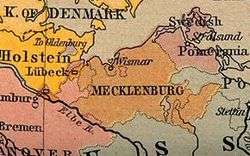

The Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin was a duchy in northern Germany created in 1701, when Frederick William and Adolphus Frederick II divided the Duchy of Mecklenburg between Schwerin and Strelitz. Ruled by the successors of the Nikloting House of Mecklenburg, Mecklenburg-Schwerin remained a state of the Holy Roman Empire along the Baltic Sea littoral between Holstein-Glückstadt and Duchy of Pomerania.

Origins

The dynasty's progenitor, Niklot (1090–1160), was a chief of the Slavic Obotrite tribal federation, who fought against the advancing Saxons and was finally defeated in 1160 by Henry the Lion in the course of the Wendish Crusade. Niklot's son, Pribislav, submitted himself to Henry, and in 1167 came into his paternal inheritance as the first Prince of Mecklenburg.

After several divisions among Pribislav's descendants, Henry II of Mecklenburg (1266–1329) until 1312 acquired the lordships of Stargard and Rostock, and bequeathed the reunified Mecklenburg lands – except the County of Schwerin and Werle – to his sons, Albert II and John. After they both had received the ducal title, the former lordship of Stargard was recreated as the Duchy of Mecklenburg-Stargard for John in 1352. Albert II retained the larger western part of Mecklenburg, and after he acquired the former County of Schwerin in 1358, he made Schwerin his residence.

In 1363 Albert's son, Duke Albert III, campaigned in Sweden, where he was crowned king one year later. In 1436, William, the last Lord of Werle, died without a male heir. Because William's son-in-law, Ulric II of Mecklenburg-Stargard, had no issue, his line became extinct upon Ulric's death in 1471. All possessions fell back to Duke Henry IV of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, who was then the sole ruler over all of Mecklenburg.

In 1520 Henry's grandsons, Henry V and Albert VII, again divided the duchy, creating the subdivision of Mecklenburg-Güstrow, which Duke Adolf Frederick I of Mecklenburg-Schwerin inherited in 1610. In a second partition of 1621, he granted Güstrow to his brother, John Albert II. Both were deposed in 1628 by Albrecht von Wallenstein, as they had supported Christian IV of Denmark in the Thirty Years' War. Nevertheless, the Swedish Empire forced their restoration three years later. When John Albert II's son, Duke Gustav Adolph, died without male heirs in 1695, Mecklenburg was reunited once more under Frederick William.

History

In June 1692, when Christian Louis I died in exile and without sons, a dispute arose about the succession to his duchy between his brother, Adolphus Frederick II, and his nephew, Frederick William. The emperor and the rulers of Kingdom of Sweden and of Electorate of Brandenburg took part in this struggle, which was intensified three years later, when on the death of Gustav Adolph, the family ruling over Mecklenburg-Güstrow became extinct. In 1701, with the endorsement of the Imperial state of the Lower Saxon Circle, the Treaty of Hamburg (1701) was signed and the final division of the country was made. Mecklenburg was divided between the two claimants. The Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin was given to Frederick William, and the Duchy of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, roughly a recreation of the medieval Stargard lordship, to Adolphus Frederick II. At the same time, the principle of primogeniture was reasserted, and the right of summoning the joint Landtag was reserved to the ruler of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. Continued conflicts and partitions weakened the rule of the dukes and affirmed the reputation of Mecklenburg as one of the most backward territories of the Empire.

Mecklenburg-Schwerin began its existence during a series of constitutional struggles between the duke and the nobles. The heavy debt incurred by Karl Leopold, who had joined Russian Empire in a war against Kingdom of Sweden, brought matters to a crisis; Charles VI interfered, and in 1728 the imperial court of justice declared the duke incapable of governing. His brother, Christian Ludwig II, was appointed administrator of the duchy. Under this prince, who became ruler de jure in 1747, the Convention of Rostock, by which a new constitution was framed for the duchy, was signed in April 1755. By this instrument, all power was in the hands of the duke, the nobles, and the upper classes generally; the lower classes were entirely unrepresented. During the Seven Years' War, Frederick II took up a hostile attitude towards Frederick the Great, and in consequence Mecklenburg-Schwerin was occupied by the Kingdom of Prussia. In other ways his rule was beneficial to the country. In the early years of the French Revolutionary Wars, Frederick Francis I remained neutral, and in 1803 he regained Wismar from Kingdom of Sweden. In 1806 the land was overrun by the First French Empire, and in 1808 he joined the Confederation of the Rhine. He was the first member of the confederation to abandon Napoleon, to whose armies he had sent a contingent, and in 1813–1814 he fought against France.

Aftermath

With the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Frederick Francis I of Mecklenburg-Schwerin received the title of Grand Duke. After the fall of the monarchies in 1918 resulting from World War I, the Grand Duchy became the Free State of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. On 1 January 1934 it was united with the neighbouring Free State of Mecklenburg-Strelitz (both today part of the Bundesland Mecklenburg-Vorpommern).

References

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.