Dune (novel)

_First_edition.jpg) First edition cover | |

| Author | Frank Herbert |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | John Schoenherr |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Series | Dune series |

| Genre | Soft science fiction [1][2] |

| Published | August 1, 1965 |

| Publisher | Chilton Books |

| Media type | Print (hardcover & paperback) |

| Pages | 412 |

| Followed by | Dune Messiah |

Dune is a 1965 epic science fiction novel by American author Frank Herbert. It tied with Roger Zelazny's This Immortal for the Hugo Award in 1966,[3] and it won the inaugural Nebula Award for Best Novel.[4] It is the first installment of the Dune saga, and in 2003 was cited as the world's best-selling science fiction novel.[5][6]

Set in the distant future amidst a feudal interstellar society in which noble houses, in control of individual planets, owe allegiance to the Padishah Emperor, Dune tells the story of young Paul Atreides, whose noble family accepts the stewardship of the desert planet Arrakis. As this planet is the only source of the "spice" melange, the most important and valuable substance in the universe, control of Arrakis is a coveted — and dangerous — undertaking. The story explores the multi-layered interactions of politics, religion, ecology, technology, and human emotion, as the forces of the empire confront each other in a struggle for the control of Arrakis and its "spice".[7]

Herbert wrote five sequels: Dune Messiah, Children of Dune, God Emperor of Dune, Heretics of Dune, and Chapterhouse: Dune. The first novel also inspired a 1984 film adaptation by David Lynch, the 2000 Sci-Fi Channel miniseries Frank Herbert's Dune and its 2003 sequel Frank Herbert's Children of Dune (which combines the events of Dune Messiah and Children of Dune), computer games, several board games, songs, and a series of followups, including prequels and sequels, that were co-written by Kevin J. Anderson and the author's son, Brian Herbert, starting in 1999.[8]

Since 2009, the names of planets from the Dune novels have been adopted for the real-world nomenclature of plains and other features on Saturn's moon Titan.[9][10][11]

Origins

After his novel The Dragon in the Sea was published in 1957, Herbert traveled to Florence, Oregon, at the north end of the Oregon Dunes. Here, the United States Department of Agriculture was attempting to use poverty grasses to stabilize the sand dunes. Herbert claimed in a letter to his literary agent, Lurton Blassingame, that the moving dunes could "swallow whole cities, lakes, rivers, highways."[12] Herbert's article on the dunes, "They Stopped the Moving Sands", was never completed – and only published decades later in The Road to Dune – but its research sparked Herbert's interest in ecology.

Herbert spent the next five years researching, writing, and revising a literary work that was eventually serialized in Analog magazine from 1963 to 1965 as two shorter works, Dune World and The Prophet of Dune.[13][14] Herbert dedicated his work "to the people whose labors go beyond ideas into the realm of 'real materials'—to the dry-land ecologists, wherever they may be, in whatever time they work, this effort at prediction is dedicated in humility and admiration." The serialized version was expanded, reworked, and submitted to more than twenty publishers, each of whom rejected it. The novel, Dune, was finally accepted and published in August 1965 by Chilton Books, a printing house better known for publishing auto repair manuals.

Synopsis

Setting

More than 21,000 years in the future,[15][16][17] humanity has settled on countless habitable planets, which are ruled by aristocratic Great Houses that owe allegiance to the Padishah Emperor Shaddam IV. Though many forms of science and technology have evolved greatly since the twentieth century, artificial intelligence and advanced computers are prohibited. Due to the absence of these technologies, humans have adapted their minds to become capable of extremely complex tasks, including mental computing, a task undertaken by trained Mentats. The powerful, matriarchal Bene Gesserit, who hope to further the human race through controlled breeding, and the Spacing Guild, which holds a legal monopoly on interstellar travel, both rely on the "spice" melange to facilitate their advanced mental abilities. The use of melange also improves general health, extends life and can bestow limited prescience.

As melange can be found only on the desert planet Arrakis, it is extremely valuable and is often used as currency. The CHOAM corporation, which determines the income and financial leverage of each Great House, controls allocation of melange. The Spacing Guild's Navigators depend on the prescience melange provides to safely plot the travels of their ships, called heighliners, enormous freighters capable of transporting people, goods, and non-interstellar spacecraft at faster than light speeds. The Bene Gesserit sisterhood depends on mental and physical abilities provided by melange, powers that are found to be even more advanced in Bene Gesserit Reverend Mothers, who have undergone a deadly ritual which unlocks their Other Memory, the ego and experiences of one's female ancestors. Due to Reverend Mothers' inability to access the memories of their male ancestors, the Bene Gesserit have a secret, millennia-old breeding program, with a goal of producing a male Bene Gesserit, called the Kwisatz Haderach. The Kwisatz Haderach would be capable of accessing all male ancestral memories and could possess "organic mental powers" that can "bridge space and time".[18] With this Kwisatz Haderach under their control, the Bene Gesserit hope to better guide humanity toward their goals, and at the time of the novel they believe that this plan is nearing fruition.

The planet Arrakis itself is completely covered in a hostile desert ecosystem, however it is sparsely populated by a human population of seemingly-native Fremen, ferocious fighters who have adapted to the harsh climate and secretly can ride the planet's giant sandworms. The Fremen also have complex rituals and systems focusing on the value and conservation of water on their arid planet; they conserve the water distilled from their dead, consider spitting an honorable greeting, and view tears shed for the dead as a most profound tribute or sign of reverence (seeing as the water is desperately needed by the living). The novel suggests that the Fremen have even adapted to the environment physiologically, with their blood able to clot almost instantly to prevent water loss.[19] The Fremen culture also values melange, which is found in the desert and harvested with great risk from attacking sandworms, who are attracted to any rhythmic activity on the dunes. As they have done on other planets with populations considered to be superstitious, Bene Gesserit missionaries have implanted religions and prophecies on Arrakis that can be used to the advantage of any Bene Gesserit who may find herself on the planet. This manipulation has given the Fremen a belief in a male messiah, the Lisan al-Gaib, or "voice of the outer world". The Lisan al-Gaib is prophesied to one day come from off-world to transform Arrakis into a more hospitable world.[20]

Plot

Padishah Emperor Shaddam IV of House Corrino grants Duke Leto Atreides control of the lucrative spice-mining operations on Arrakis. Though Leto and his advisors highly suspect the boon to be some sort of trap, Leto believes he can avoid it; additionally, it is an opportunity for House Atreides to gain power and wealth, and politically Leto cannot refuse. The Emperor has indeed become threatened by Leto's growing popularity within the convocation of ruling Houses known as the Landsraad, and decides that House Atreides must be destroyed. Unable to risk an overt attack on a single House without suffering a backlash from the Landsraad, the Emperor instead plots to use the centuries-old feud between House Atreides and House Harkonnen to disguise his assault, enlisting the brilliant and power-hungry Baron Vladimir Harkonnen in his plan to trap and eliminate the Atreides. Complicating the political intrigue is the fact that Leto's son Paul Atreides is an essential part of the Bene Gesserit's secret, centuries-old breeding program. Though ordered to use her physiological training to conceive a daughter, Leto's concubine, the Bene Gesserit Lady Jessica, had instead chosen to give the Duke a male heir out of love for him. The Bene Gesserit leader Reverend Mother Mohiam, not used to being defied, is wary of the potential repercussions of Jessica's choice on both young Paul's genetics and the breeding program itself.

On Arrakis, the Atreides are able to thwart initial Harkonnen traps and complications while simultaneously, through Leto's Swordmaster Duncan Idaho, building trust with the mysterious desert Fremen, with whom they hope to ally. However, the Atreides are ultimately unable to withstand a devastating Harkonnen attack, supported by the Emperor's fearsome, virtually invincible Sardaukar troops disguised as Harkonnen troops and made possible by a traitor within House Atreides itself, the Suk doctor Wellington Yueh. House Atreides is scattered, and of its principal retainers, Mentat Thufir Hawat is taken by the Baron Harkonnen and eventually provides his reluctant services whilst formulating a plan to undermine the Baron; the troubadour-soldier Gurney Halleck escapes with the aid of smugglers, whom he joins; and Duncan Idaho is killed defending Paul and Jessica. Per his bargain, Yueh delivers a captive Leto to the Baron, but double-crosses the Harkonnens by ensuring that Paul and Jessica escape. He also provides Leto with a poison-gas capsule in the form of a false tooth, which Yueh instructs a drugged Leto to use to simultaneously commit suicide and assassinate Harkonnen. The Baron kills Yueh, and Leto dies in his failed attempt on the Baron's life, though the Baron's twisted Mentat Piter De Vries dies with him. Paul and Jessica flee into the deep desert, escaping the Harkonnens by following instructions laid out in advance by the traitor Yueh. They successfully navigate through a sandstorm, a seemingly impossible task that leaves the Baron convinced that both of them are dead.

Jessica's Bene Gesserit abilities and Paul's developing skills help them join a band of Fremen. Paul and his mother quickly learn Fremen ways while teaching the Fremen what they call the "weirding way", or the Bene Gesserit method of fighting. Jessica becomes a Reverend Mother, ingesting the poisonous Water of Life while pregnant with her second child; this unborn daughter Alia is subjected to the same ordeal, acquiring the full abilities of a Reverend Mother before even being born. Paul takes a Fremen lover, Chani, with whom he fathers a son. Two years pass, and Paul increasingly recognizes the strength of the Fremen fighting force and their potential to overtake even the "unstoppable" Sardaukar and win back Arrakis. The spice diet of the Fremen and his own developing mental powers cause Paul's prescience to increase dramatically, allowing his foresight of future "paths" of possible events. Regarded by the Fremen as their prophesied messiah, Paul grows in influence and begins a jihad against Harkonnen rule of the planet under his new Fremen name, Muad'Dib. However, Paul becomes aware through his prescience that, if he is not careful, the Fremen will extend that jihad against all the known universe, which Paul describes as a humanity-spanning subconscious effort to avoid genetic stagnation.

Both the Emperor and the Baron Harkonnen show increasing concern at the fervor of religious fanaticism shown on Arrakis for this "Muad'Dib", not guessing that this leader is the presumed-dead Paul. Harkonnen plots to send his nephew and heir-presumptive Feyd-Rautha as a replacement for his more brutish nephew Glossu Rabban — who is in charge of the planet — with the hope of gaining the respect of the population. However, the Emperor is highly suspicious of the Baron and sends spies to watch his movements. Hawat explains the Emperor's suspicions: the Sardaukar, all but invincible in battle, are trained on the prison planet Salusa Secundus, whose inhospitable conditions allow only the best to survive. Arrakis serves as a similar crucible, and the Emperor fears that the Baron could recruit from it a fighting force to rival his Sardaukar, just as House Atreides had intended before their destruction.

Paul is reunited with Gurney. Completely loyal to the Atreides, Gurney is convinced that Jessica is the traitor who caused the House's downfall, and nearly kills her before being stopped by Paul. Disturbed that his prescience had not predicted this possibility, Paul decides to take the Water of Life, an act which will either confirm his status as the Kwisatz Haderach or kill him. After three weeks in a near-death state, Paul emerges with his powers refined and focused; he is able to see past, present, and future at will, down both male and female lines. Looking into space, he sees that the Emperor and the Harkonnens have amassed a huge armada to invade the planet and regain control. Paul also realizes that his ability to destroy all spice production on Arrakis using the Water of Life is his means of seizing control of it.

In an Imperial attack on a Fremen settlement, Paul and Chani's infant son Leto II is killed and the four-year-old Alia is captured by Sardaukar. She is brought to the planet's capital Arrakeen, where the Baron Harkonnen is attempting to thwart the Fremen jihad under the close watch of the Emperor. The Emperor is surprised at Alia's defiance of his power and her confidence in her brother, whom she reveals to be Paul Atreides. At that moment, under cover of a gigantic sandstorm, Paul and his army of Fremen attack the city riding sandworms; Alia assassinates the Baron and escapes during the confusion. Paul defeats the Sardaukar and confronts the Emperor, threatening to destroy the spice, thereby ending space travel and crippling both Imperial power and the Bene Gesserit in one blow. The new Baron Harkonnen, Feyd-Rautha, challenges Paul to a knife duel to the death in a final attempt to stop his overthrow, but is defeated despite an attempt at treachery. Realizing that Paul is capable of doing all he has threatened, the Emperor is forced to abdicate and to promise his daughter Princess Irulan in marriage to Paul. Paul ascends the throne, his control of Arrakis and the spice establishing a new kind of power over the Empire that will change the face of the known universe. But in spite of his power, Paul discovers that he will not be able to stop the jihad in his visions. His legendary state among the Fremen has grown beyond his power to control it.[20]

Characters

House Atreides

- Paul Atreides, the Duke's son, and main character of the novel.

- Duke Leto Atreides, head of House Atreides

- Lady Jessica, Bene Gesserit and concubine of the Duke, mother of Paul and Alia

- Alia Atreides, Paul's younger sister

- Thufir Hawat, Mentat and Master of Assassins to House Atreides

- Gurney Halleck, staunchly loyal troubadour warrior of the Atreides

- Duncan Idaho, Swordmaster for House Atreides, graduate of the Ginaz School

- Wellington Yueh, Suk doctor for the Atreides, who is secretly working for House Harkonnen

House Harkonnen

- Baron Vladimir Harkonnen, head of House Harkonnen

- Piter De Vries, twisted Mentat

- Feyd-Rautha, nephew and heir-presumptive of the Baron

- Glossu "Beast" Rabban, also called Rabban Harkonnen, older nephew of the Baron

- Iakin Nefud, Captain of the Guard

House Corrino

- Shaddam IV, Padishah Emperor of the Known Universe (the Imperium)

- Princess Irulan, Shaddam's eldest daughter and heir, also a historian

- Count Hasimir Fenring, genetic eunuch and the Emperor's closest friend, advisor, and "errand boy"

Bene Gesserit

- Reverend Mother Gaius Helen Mohiam, Bene Gesserit schemer, the Emperor's Truthsayer

- Lady Margot Fenring, Bene Gesserit wife of Count Fenring

Fremen

- The Fremen, "native" inhabitants of Arrakis

- Stilgar, Fremen Naib (chieftain) of Sietch Tabr

- Chani, Paul's Fremen concubine

- Liet-Kynes, the Imperial Planetologist on Arrakis and father of Chani, as well as a revered figure among the Fremen

- Mapes, head housekeeper of imperial residence on Arrakis

- Jamis, Fremen killed by Paul in ritual duel

- Harah, wife of Jamis and later servant to Paul

- Ramallo, reverend mother of Sietch Tabr

Smugglers

- Esmar Tuek, a powerful smuggler and the father of Staban Tuek.

- Staban Tuek, the son of Esmar Tuek. A powerful smuggler who befriends and takes in Gurney Halleck and his surviving men after the attack on the Atreides.

Analysis

The Dune series is a landmark of soft science fiction. Herbert deliberately suppressed technology in his Dune universe so he could address the politics of humanity, rather than the future of humanity's technology. Dune considers the way humans and their institutions might change over time.[1][2] Director John Harrison, who adapted Dune for Syfy's 2000 miniseries, called the novel a universal and timeless reflection of "the human condition and its moral dilemmas", and said:

A lot of people refer to Dune as science fiction. I never do. I consider it an epic adventure in the classic storytelling tradition, a story of myth and legend not unlike the Morte d'Arthur or any messiah story. It just happens to be set in the future ... The story is actually more relevant today than when Herbert wrote it. In the 1960's, there were just these two colossal superpowers duking it out. Today we're living in a more feudal, corporatized world more akin to Herbert's universe of separate families, power centers and business interests, all interrelated and kept together by the one commodity necessary to all.[21]

Each chapter of Dune begins with an epigraph excerpted from the fictional writings of the character Princess Irulan. In forms such as diary entries, historical commentary, biography, quotations and philosophy, these writings set tone and provide exposition, context and other details intended to enhance understanding of Herbert's complex fictional universe and themes.[22][23][24]

Environmentalism and ecology

Dune has been called the "first planetary ecology novel on a grand scale".[25] After the publication of Silent Spring by Rachel Carson in 1962, science fiction writers began treating the subject of ecological change and its consequences. Dune responded in 1965 with its complex descriptions of Arrakis life, from giant sandworms (for whom water is deadly) to smaller, mouse-like life forms adapted to live with limited water. The inhabitants of the planet, the Fremen, must compromise with the ecosystem in which they live, sacrificing some of their desire for a water-laden planet to preserve the sandworms which are so important to their culture. Dune was followed in its creation of complex and unique ecologies by other science fiction books such as A Door into Ocean (1986) and Red Mars (1992).[25] Environmentalists have pointed out that Dune's popularity as a novel depicting a planet as a complex—almost living—thing, in combination with the first images of earth from space being published in the same time period, strongly influenced environmental movements such as the establishment of the international Earth Day.[26]

Declining empires

Lorenzo DiTommaso compared Dune's portrayal of the downfall of a galactic empire to Edward Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire which argues that Christianity led to the fall of Ancient Rome. In "History and Historical Effect in Frank Herbert's Dune" (1992), Lorenzo DiTommaso outlines similarities between the two works by highlighting the excesses of the Emperor on his home planet of Kaitain and of the Baron Harkonnen in his palace. The Emperor loses his effectiveness as a ruler from excess of ceremony and pomp. The hairdressers and attendants he brings with him to Arrakis are even referred to as "parasites". The Baron Harkonnen is similarly corrupt, materially indulgent, and sexually decadent. Gibbon's Decline and Fall blames the fall of Rome on the rise of Christianity. Gibbon claimed that this exotic import from a conquered province weakened the soldiers of Rome and left it open to attack. Similarly, the Emperor's Sardaukar fighters are little match for the Fremen of Dune because of the Sardaukar's overconfidence and the Fremen's capacity for self-sacrifice. The Fremen put the community before themselves in every instance, while the world outside wallows in luxury at the expense of others.[27]

Middle Eastern references

Many words, titles and names (e.g. the Padishah Emperor Shaddam IV, Hawat, Bashar, Harq-al-Ada) in the Dune universe as well as a large number of words in the language of the Fremen people are derived or taken directly from Persian and Arabic (e.g. erg, the Arabic word for a broad flat landform, is used frequently throughout the novel). Paul's messianic name (Muad'Dib) means in Arabic 'the teacher or maker of politeness or literature'. The Fremen language is also embedded with Islamic terms such as, jihad, Mahdi, Shaitan, and the personal bodyguard of Paul Muad'Dib Fedaykin is a transliteration of the Persian Feda'yin.[28] As a foreigner who adopts the ways of a desert-dwelling people and then leads them in a military capacity, Paul Atreides' character bears many similarities to the historical T. E. Lawrence.[29]

Gender dynamics

Paul's approach to power consistently requires his upbringing under the female-oriented Bene Gesserit, who operate as a long-dominating shadow government behind all of the great houses and their marriages or divisions. A central theme of the book is the connection, in Jessica's son, of this female aspect with his male aspect. In a Bene Gesserit test early in the book, it is implied that people are generally "inhuman" in that they irrationally place desire over self-interest and reason. This applies Herbert's philosophy that humans are not created equal, while equal justice and equal opportunity are higher ideals than mental, physical, or moral equality.[30] Margery Hourihan even calls the main character's mother, Jessica, "by far the most interesting character in the novel"[31] and pointing out that while her son approaches a power which makes him almost alien to the reader, she remains human. Throughout the novel, she struggles to maintain power in a male-dominated society, and manages to help her son at key moments in his realization of power.[31]

Heroism

I am showing you the superhero syndrome and your own participation in it.— Frank Herbert[32]

Throughout Paul's rise to superhuman status, he follows a plotline common to many stories describing the birth of a hero. He has unfortunate circumstances forced onto him. After a long period of hardship and exile, he confronts and defeats the source of evil in his tale.[33][34] As such, Dune is representative of a general trend beginning in 1960s American science fiction in that it features a character who attains godlike status through scientific means.[35] Eventually, Paul Atreides gains a level of omniscience which allows him to take over the planet and the galaxy, and causing the Fremen of Arrakis to worship him like a god. Author Frank Herbert said in 1979, "The bottom line of the Dune trilogy is: beware of heroes. Much better [to] rely on your own judgment, and your own mistakes."[36] He wrote in 1985, "Dune was aimed at this whole idea of the infallible leader because my view of history says that mistakes made by a leader (or made in a leader's name) are amplified by the numbers who follow without question."[37]

Juan A. Prieto-Pablos says Herbert achieves a new typology with Paul's superpowers, differentiating the heroes of Dune from earlier heroes such as Superman, van Vogt's Gilbert Gosseyn and Henry Kuttner's telepaths. Unlike previous superheroes who acquire their powers suddenly and accidentally, Paul's are the result of "painful and slow personal progress." And unlike other superheroes of the 1960s—who are the exception among ordinary people in their respective worlds—Herbert's characters grow their powers through "the application of mystical philosophies and techniques." For Herbert, the ordinary person can develop incredible fighting skills (Fremen, Ginaz swordsmen and Sardaukar) or mental abilities (Bene Gesserit, Mentats, Spacing Guild Navigators).[38]

Zen

Early in his newspaper career, Herbert was introduced to Zen by two Jungian psychologists.[39] Throughout the Dune series and particularly in Dune, Herbert employs concepts and forms borrowed from Zen Buddhism.[40] The Fremen are Zensunni adherents, and many of Herbert's epigraphs are Zen-spirited.[41] In "Dune Genesis" he wrote:

What especially pleases me is to see the interwoven themes, the fuguelike relationships of images that exactly replay the way Dune took shape. As in an Escher lithograph, I involved myself with recurrent themes that turn into paradox. The central paradox concerns the human vision of time. What about Paul's gift of prescience-the Presbyterian fixation? For the Delphic Oracle to perform, it must tangle itself in a web of predestination. Yet predestination negates surprises and, in fact, sets up a mathematically enclosed universe whose limits are always inconsistent, always encountering the unprovable. It's like a koan, a Zen mind breaker. It's like the Cretan Epimenides saying, "All Cretans are liars."[30]

Reception

Dune tied with Roger Zelazny's This Immortal for the Hugo Award in 1966,[3] and won the inaugural Nebula Award for Best Novel.[4] Reviews of the novel have been largely positive, and Dune is considered by some critics to be the best science fiction book ever written.[42] As of 2000 it had sold over 12 million copies worldwide,[21] and it has been regularly cited as one of the world's best-selling science fiction novels.[5][6]

Science fiction author Arthur C. Clarke has described it as "unique" and claimed "I know nothing comparable to it except Lord of the Rings."[43] Robert A. Heinlein described Dune as "Powerful, convincing, and most ingenious."[43] It was called "One of the monuments of modern science fiction" by the Chicago Tribune, while the Washington Post described it as "A portrayal of an alien society more complete and deeply detailed than any other author in the field has managed ... a story absorbing equally for its action and philosophical vistas ... An astonishing science fiction phenomenon."[43]

Algis Budrys praised Dune for the vividness of its imagined setting, saying "The time lives. It breathes, it speaks, and Herbert has smelt it in his nostrils." But Budrys also found that "Dune turns flat and tails off at the end. ... [T]ruly effective villains simply simper and melt; fierce men and cunning statesmen and seeresses all bend before this new Messiah." He faults in particular Herbert's decision to kill Paul's infant son offstage, with no apparent emotional impact, saying "you cannot be so busy saving a world that you cannot hear an infant shriek."[44]

Tamara I. Hladik wrote that the story "crafts a universe where lesser novels promulgate excuses for sequels. All its rich elements are in balance and plausible—not the patchwork confederacy of made-up languages, contrived customs, and meaningless histories that are the hallmark of so many other, lesser novels."[45]

Writing for The New Yorker, Jon Michaud praises Herbert's "clever authorial decision" to exclude robots and computers ("two staples of the genre") from his fictional universe, but suggests that this may be one explanation why Dune lacks "true fandom among science-fiction fans" to the extent that it "has not penetrated popular culture in the way that The Lord of the Rings and Star Wars have".[46]

Gender and sexuality issues

Kathy Gower criticizes Dune in the essay anthology Mother Was Not a Person, arguing that, although the book has been praised for its portrayal of people in a mystical world, the prominence of its female characters is significantly lower than that of the males. In her view, women in Dune culture are largely left to domestic duties, and the exclusively female Bene Gesserit religious cult resembles age-old notions of witchcraft. Women in this religion are feared and hated by the men. They also never use their power to aid themselves, only the men around them, and their greatest desire is to bring a man into their religion.[47] Science-fiction author and literary critic Samuel R. Delany has complained that the book's only portrayal of a homosexual character, the vile pervert Baron Harkonnen, is negative.[48]

First edition prints and manuscripts

The first edition of Dune is one of the most valuable in science fiction book collecting, and copies have gone for more than $10,000 at auction.[49] The Chilton first edition of the novel is 9.25 inches tall, with bluish green boards and a price of $5.95 on the dust jacket, and notes Toronto as the Canadian publisher on the copyright page. Up to this point, Chilton had been publishing only automobile repair manuals.[50] Other editions similar to this one, such as book club editions, exist.

California State University, Fullerton's Pollack Library has several of Herbert's draft manuscripts of Dune and other works, with the author's notes, in their Frank Herbert Archives.[51]

Adaptations

Early stalled attempts

In 1971, the production company Apjac International (APJ) (headed by Arthur P. Jacobs) optioned the rights to film Dune. As Jacobs was busy with other projects, such as the sequel to Planet of the Apes, Dune was delayed for another year. Jacobs' first choice for director was David Lean, but he turned down the offer. Charles Jarrott was also considered to direct. Work was also under way on a script while the hunt for a director continued. Initially, the first treatment had been handled by Robert Greenhut, the producer who had lobbied Jacobs to make the movie in the first place, but subsequently Rospo Pallenberg was approached to write the script, with shooting scheduled to begin in 1974. However, Jacobs died in 1973.[52]

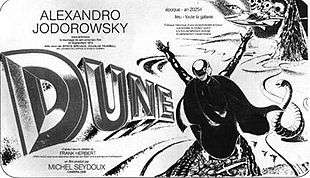

In December 1974, a French consortium led by Jean-Paul Gibon purchased the film rights from APJ, with Alejandro Jodorowsky set to direct.[53] In 1975, Jodorowsky planned to film the story as a ten-hour feature, in collaboration with Salvador Dalí, Orson Welles, Gloria Swanson, David Carradine, Geraldine Chaplin, Alain Delon, Hervé Villechaize, and Mick Jagger. It was at first proposed to score the film with original music by Karlheinz Stockhausen, Henry Cow, and Magma; later on, the soundtrack was to be provided by Pink Floyd.[54] Jodorowsky set up a pre-production unit in Paris consisting of Chris Foss, a British artist who designed covers for science fiction periodicals, Jean Giraud (Moebius), a French illustrator who created and also wrote and drew for Metal Hurlant magazine, and H. R. Giger.[53] Moebius began designing creatures and characters for the film, while Foss was brought in to design the film's space ships and hardware.[53] Giger began designing the Harkonnen Castle based on Moebius' storyboards. Jodorowsky's son Brontis Jodorowsky was to play Paul Atreides.[53] Dan O'Bannon was to head the special effects department.[53]

Dalí was cast as the Emperor.[53] Dalí later demanded to be paid $100,000 per hour; Jodorowsky agreed, but tailored Dalí's part to be filmed in one hour, drafting plans for other scenes of the emperor to use a mechanical mannequin as substitute for Dalí.[53] According to Giger, Dalí was "later invited to leave the film because of his pro-Franco statements".[55] Just as the storyboards, designs, and script were finished, the financial backing dried up. Frank Herbert traveled to Europe in 1976 to find that $2 million of the $9.5 million budget had already been spent in pre-production, and that Jodorowsky's script would result in a 14-hour movie ("It was the size of a phone book", Herbert later recalled). Jodorowsky took creative liberties with the source material, but Herbert said that he and Jodorowsky had an amicable relationship. Jodorowsky said in 1985 that he found the Dune story mythical and had intended to recreate it rather than adapt the novel; though he had an "enthusiastic admiration" for Herbert, Jodorowsky said he had done everything possible to distance the author and his input from the project.[53] Although Jodorowsky was embittered by the experience, he stated that the Dune project changed his life. O'Bannon entered a psychiatric hospital after the production failed, and worked on thirteen scripts; the last of which became Alien.[53] A 2013 documentary, Jodorowsky's Dune, was made about Jodorowsky's failed attempt at an adaptation.

In 1976 Dino De Laurentiis acquired the rights from Gibon's consortium. De Laurentiis commissioned Herbert to write a new screenplay in 1978; the script Herbert turned in was 175 pages long, the equivalent of nearly three hours of screen time. De Laurentiis then hired director Ridley Scott in 1979, with Rudy Wurlitzer writing the screenplay and H. R. Giger retained from the Jodorowsky production. Scott intended to split the book into two movies. He worked on three drafts of the script, using The Battle of Algiers as a point of reference, before moving on to direct another science fiction film, Blade Runner (1982). As he recalls, the pre-production process was slow, and finishing the project would have been even more time-intensive:

But after seven months I dropped out of Dune, by then Rudy Wurlitzer had come up with a first-draft script which I felt was a decent distillation of Frank Herbert's. But I also realised Dune was going to take a lot more work—at least two and a half years' worth. And I didn't have the heart to attack that because my older brother Frank unexpectedly died of cancer while I was prepping the De Laurentiis picture. Frankly, that freaked me out. So I went to Dino and told him the Dune script was his.

- —From Ridley Scott: The Making of his Movies by Paul M. Sammon

1984 film by David Lynch

In 1981, the nine-year film rights were set to expire. De Laurentiis re-negotiated the rights from the author, adding to them the rights to the Dune sequels (written and unwritten). After seeing The Elephant Man, producer Raffaella De Laurentiis decided that David Lynch should direct the movie. Around that time Lynch received several other directing offers, including Return of the Jedi. He agreed to direct Dune and write the screenplay even though he had not read the book, known the story, or even been interested in science fiction.[56] Lynch worked on the script for six months with Eric Bergen and Christopher De Vore. The team yielded two drafts of the script before it split over creative differences. Lynch would subsequently work on five more drafts.

This first film of Dune, directed by Lynch, was released in 1984, nearly 20 years after the book's publication. Though Herbert said the book's depth and symbolism seemed to intimidate many filmmakers, he was pleased with the film, saying that "They've got it. It begins as Dune does. And I hear my dialogue all the way through. There are some interpretations and liberties, but you're gonna come out knowing you've seen Dune."[57] Reviews of the film were not as favorable, saying that it was incomprehensible to those unfamiliar with the book, and that fans would be disappointed by the way it strayed from the book's plot.[58]

2000 miniseries by John Harrison

In 2000, John Harrison adapted the novel into Frank Herbert's Dune, a miniseries which premiered on the Sci-Fi Channel.[21] As of 2004, the miniseries was one of the three highest-rated programs broadcast on the Sci-Fi Channel.[59]

Further film attempts

In 2008, Paramount Pictures announced that they would produce a new film based on the book, with Peter Berg attached to direct.[60][61] Producer Kevin Misher, who spent a year securing the rights from the Herbert estate, was to be joined by Richard Rubinstein and John Harrison (of both Sci Fi Channel miniseries) as well as Sarah Aubrey and Mike Messina.[60] The producers stated that they were going for a "faithful adaptation" of the novel, and considered "its theme of finite ecological resources particularly timely."[60] Science fiction author Kevin J. Anderson and Frank Herbert's son Brian Herbert, who had together written multiple Dune sequels and prequels since 1999, were attached to the project as technical advisors.[62] In October 2009, Berg dropped out of the project, later saying that it "for a variety of reasons wasn't the right thing" for him.[63] Subsequently, with a script draft by Joshua Zetumer, Paramount reportedly sought a new director who could do the film for under $175 million.[64] In 2010, Pierre Morel was signed on to direct, with screenwriter Chase Palmer incorporating Morel's vision of the project into Zetumer's original draft.[65][66] By November 2010, Morel left the project.[67] Paramount finally dropped plans for a remake in March 2011.[68]

In November 2016, Legendary Pictures acquired the film and TV rights for Dune.[69][70]

Audiobook

In 1993, Recorded Books Inc. released a 20-disc audio book narrated by George Guidall. In 2007, Audio Renaissance released an audio book narrated by Simon Vance with some parts acted out by Scott Brick, Orlagh Cassidy, Euan Morton, and other performers.

Cultural influence

Dune has been widely influential, inspiring other novels, music, films (including Star Wars), television, games, and comic books.[71] Real world extra-terrestrial locations have been named after elements from the novel and its sequels. Dune was parodied in 1984's National Lampoon's Doon by Ellis Weiner.[72]

German electronic music pioneer Klaus Schulze released a 1979 LP titled Dune featuring motifs and lyrics inspired by the novel. A similar musical project "Visions of Dune" was released the same year by a musical project titled "Zed" led by French electronic musician Bernard Sjazner. Heavy metal band Iron Maiden wrote the song "To Tame a Land" based on the Dune story. It appears as the closing track to their 1983 album Piece of Mind. The original working title of the song was "Dune"; however, the band was denied permission to use it, with Frank Herbert's agents stating "Frank Herbert doesn't like rock bands, particularly heavy rock bands, and especially bands like Iron Maiden".[73] The same song was later covered in 2009 by American progressive metal band Dream Theater, released only on a 3-disc special edition of their album Black Clouds & Silver Linings. Dune inspired the German happy hardcore band Dune, who have released several albums with space travel-themed songs. The influential progressive hardcore band Shai Hulud took their name from Dune. "Traveller in Time", from the 1991 Blind Guardian album Tales from the Twilight World, is based mostly on Paul Atreides' visions of future and past.[74][75] The song "Near Fantastica", from the Matthew Good album Avalanche, makes reference to "litany against fear", repeating "can't feel fear, fear's the mind killer" through a section of the song.[76] In the Fatboy Slim song "Weapon of Choice", the line "If you walk without rhythm/You won't attract the worm" is a near quotation from the sections of novel in which Stilgar teaches Paul to ride sandworms. Dune also inspired the 1999 album The 2nd Moon by the German death metal band Golem, which is a concept album about the series.[77] Dune influenced Thirty Seconds to Mars on their self-titled debut album.[78] The Youngblood Brass Band's song "Is an Elegy" on Center:Level:Roar references "Muad'Dib", "Arrakis" and other elements from the novel.[79] Canadian musician Claire Boucher, better known as Grimes, has cited Dune as her favourite novel. Her debut album Geidi Primes and many of the songs on the album are references to the Dune universe. The online game Lost Souls includes Dune-derived elements, including sandworms and melange—addiction to which can produce psychic talents.[80]

The Apollo 15 astronauts named a small crater after the novel during the 1971 mission,[81] and the name was formally adopted by the International Astronomical Union in 1973.[82] Since 2009, the names of planets from the Dune novels have been adopted for the real-world nomenclature of plains and other features on Saturn's moon Titan.[9][10][11]

See also

- Dune universe

- List of Dune Houses

- List of Dune characters

- List of Dune terminology

- List of fictional books § Works invented by Frank Herbert

- Soft science fiction

References

- 1 2 Hanson, Matt (2005). Building Sci-fi Moviescapes: The Science Behind the Fiction. Gulf Professional Publishing. ISBN 9780240807720.

- 1 2 "Frank Herbert Biography". bestsciencefictionbooks.com. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- 1 2 "The Hugo Awards: 1966". TheHugoAwards.org. World Science Fiction Society. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- 1 2 "1965 Nebula Awards". NebulaAwards.com. Archived from the original on December 17, 2005. Retrieved March 17, 2010.

- 1 2 Touponce, William F. (1988). "Herbert's Reputation". Frank Herbert. Boston, Massachusetts: Twayne Publishers imprint, G. K. Hall & Co. p. 119. ISBN 0-8057-7514-5.

Locus ran a poll of readers on April 15, 1975 in which Dune 'was voted the all-time best science-fiction novel … It has sold over ten million copies in numerous editions.'

- 1 2 "SCI FI Channel Auction to Benefit Reading Is Fundamental". PNNonline.org (Internet Archive). March 18, 2003. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved September 28, 2007.

Since its debut in 1965, Frank Herbert's Dune has sold over 12 million copies worldwide, making it the best-selling science fiction novel of all time ... Frank Herbert's Dune saga is one of the greatest 20th Century contributions to literature.

- ↑ Herbert, Frank (February 3, 1969). "Interview with Dr. Willis E. McNelly". Sinanvural.com. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

During my studies of deserts, of course, and previous studies of religions, we all know that many religions began in a desert atmosphere, so I decided to put the two together because I don't think that any one story should have any one thread. I build on a layer technique, and of course putting in religion and religious ideas you can play one against the other.

- ↑ "Official Dune website: Novels". DuneNovels.com. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- 1 2 Blue, Jennifer (August 4, 2009). "USGS Astrogeology Hot Topics: New Name, Descriptor Term, and Theme Approved for Use on Titan". Astrogeology.usgs.gov. Retrieved September 8, 2010.

- 1 2 "Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature: Titan Planitiae". Planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- 1 2 "Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature: Titan Labyrinthi". Planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov. Retrieved January 3, 2015.

- ↑ The Road to Dune (2005), p. 264, letter by Frank Herbert to his agent Lurton Blassingame outlining "They Stopped the Moving Sands."

- ↑ The Road to Dune, p. 272."...Frank Herbert toyed with the story about a desert world full of hazards and riches. He plotted a short adventure novel, Spice Planet, but he set that outline aside when his concept grew into something much more ambitious."

- ↑ The Road to Dune, pp. 263-264.

- ↑ "Official site: Dune novels timeline". BrianPHerbert.com (Internet Archive). Archived from the original on April 13, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- ↑ Herbert, Frank (1965). "Appendix II: The Religion of Dune". Dune.

Mankind's movement through deep space placed a unique stamp on religion during the one hundred and ten centuries that preceded the Butlerian Jihad.

- ↑ The official Dune timeline establishes that 2000 A.D. is approximately 11,000 B.G. (Before Guild), and the events of the novel Dune begin around 10,190 A.G. (After Guild).

- ↑ Herbert, Frank (1965). "Terminology of the Imperium: KWISATZ HADERACH". Dune.

- ↑ Herbert, Frank (1965). Dune.

Jessica withdrew the blade from its sheath. How it glittered! She directed the point toward Mapes, saw a fear greater than death-panic come over the woman. Poison in the point? Jessica wondered. She tipped up the point, drew a delicate scratch with the blade's edge above Mapes' left breast. There was a thick welling of blood that stopped almost immediately. Ultrafast coagulation, Jessica thought. A moisture-conserving mutation?

- 1 2 Herbert, Frank (1965). Dune.

- 1 2 3 Stasio, Marilyn (December 3, 2000). "COVER STORY: Future Myths, Adrift in the Sands of Time". The New York Times. Retrieved August 21, 2015.

- ↑ Fritz, Steve (December 4, 2000). "DUNE: Remaking the Classic Novel". Cinescape.com. Archived from the original on March 16, 2008. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- ↑ Edison, David (February 3, 2014). "Quotes from the End of the World". Tor.com. Retrieved June 29, 2014.

- ↑ "Collected Sayings of Princess Irulan". DuneMessiah.com. Archived from the original on June 18, 2008. Retrieved November 9, 2008.

- 1 2 James, Edward; Farah Mendlesohn (2003). The Cambridge Companion to Science Fiction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 183–184. ISBN 0-521-01657-6.

- ↑ Robert L. France, ed. (2005). Facilitating Watershed Management: Fostering Awareness and Stewardship. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 105. ISBN 0-7425-3364-6.

- ↑ Lorenzo, DiTommaso (November 1992). "History and Historical Effect in Frank Herbert's Dune". Science Fiction Studies. #58, Volume 19, Part 3. DePauw.edu. pp. 311–325. Retrieved July 21, 2009.

- ↑ Herbert, Frank (1965). "Afterword: by Brian Herbert (2005)". Dune, 40th Anniversary Edition (Dune Chronicles: Book 1). Ace Books, NY. pp. 523–525. ISBN 0-441-01359-7.

- ↑ "To name one recent example, the political imbroglio involving T. E. Lawrence had profound messianic overtones. If Lawrence had been killed at a crucial point in the struggle, Herbert notes, he might well have become a new "avatar" for the Arabs. The Lawrence analogy suggested to Herbert the possibility for manipulation of the messianic impulses within a culture by outsiders with ulterior purposes. He also realized that ecology could become the focus of just such a messianic episode, here and now, in our own culture. 'It might become the new banner for a deadly crusade--an excuse for a witch hunt or worse.'

Herbert pulled all these strands together in an early version of Dune. It was a story about a hero very like Lawrence of Arabia, an outsider who went native and used religious fervor to fuel his own ambitions--in this case, to transform the ecology of the planet." pg 41, O'Reilly 1981 ibid. - 1 2 Herbert, Frank (July 1980). "Dune Genesis". Omni. FrankHerbert.org. Archived from the original on January 7, 2012. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- 1 2 Hourihan, Margery. Deconstructing the Hero: Literary Theory and Children's Literature. New York: Routledge, 1997. pp. 174-175 ISBN 0-415-14419-1

- ↑ Herbert liner notes quoted in Touponce pg 24

- ↑ Tilley, E. Allen. "The Modes of Fiction: A Plot Morphology." College English. (Feb 1978) 39.6 pp. 692-706.

- ↑ Hume, Kathryn. "Romance: A Perdurable Pattern." College English. (Oct 1974) 36.2 pp. 129-146.

- ↑ Attebery, Brian. Decoding Gender in Science Fiction. New York: Routledge, 2002. p. 66 ISBN 0-415-93949-6

- ↑ Clareson, Thomas (1992). Understanding Contemporary American Science Fiction: the Formative Period. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. pp. 169–172. ISBN 0-87249-870-0.

- ↑ Herbert, Frank (1985). "Introduction". Eye. ISBN 0-425-08398-5.

- ↑ Prieto-Pablos, Juan A. (Spring 1991). "The Ambivalent Hero of Contemporary Fantasy and Science Fiction". Extrapolation. The University of Texas at Brownsville. 32 (1): 64–80.

- ↑ "This move, in April 1949, was to prove significant, for it was in Santa Rosa that Herbert met Ralph and Irene Slattery, two psychologists who gave a crucial boost to his thinking. Any discussion of the sources of Herbert's work circles inevitably back to their names as to no others. They are the one exception to the principle that books loom larger than people as influences on his self-educated mind. Perhaps it was because they guided his reading into new avenues as well as sparked thoughtful conversation. "Those wonderful people really opened a university for me," he says. Ralph had doctorates in philosophy and psychology. Irene had been a student of Jung in Zurich. And both of them were analysts... . They really educated me in that field."...The Slatterys also introduced Herbert to Zen, the teachings of which have had a profound and continuing influence on his work." O'Reilly, Frank Herbert

- ↑ WM: Well, I caught those Zen elements from time to time, I thought ... in Dune, and in fact, the whole Zensunni school line thought was an aspect of that ...

FH: You know, don't you, that one element of the construction of this book ...it's all the way through there…that I wrote certain parts of it in haiku and other poetical forms, and then expanded them to prose to create a pace. - ↑ "They also introduced Herbert to Zen, the teachings of which had a profound influence on his life and work. The Dune series is full of Zen paradoxes that are intended to disrupt our Western logical habits of mind." pg 10, Touponce 1988

- ↑ Frans Johansson (2004). The Medici effect: breakthrough insights at the intersection of ideas, concepts, and cultures. Boston, Mass: Harvard Business School Press. p. 78. ISBN 1-59139-186-5.

- 1 2 3 "Dune 40th Anniversary Edition: Editorial Reviews". Amazon.com. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ↑ "Galaxy Bookshelf", Galaxy Science Fiction, April 1966, p.67-71

- ↑ Hladik, Tamara I. "Classic Sci-Fi Reviews: Dune". SciFi.com. Archived from the original on April 20, 2008. Retrieved April 20, 2008.

- ↑ Michaud, Jon (July 12, 2013). "Dune Endures". The New Yorker. Retrieved August 18, 2015.

- ↑ Andersen, Margret. "Science Fiction and Women". Mother Was Not a Person. Montréal: Black Rose Books, 1974. pp. 98-99 ISBN 0-919618-00-6

- ↑ Delany, Samuel R. Shorter Views: Queer Thoughts & the Politics of the Paraliterary. Hanover: Wesleyan University Press, published by University Press of New England, 1999. p. 90 ISBN 0-8195-6369-2

- ↑ Books: First Editions, Frank Herbert: Dune First Edition. (Philadelphia: Chilton Books, 1965), first edition, first printing, 412 pages, ba... (Total: 1 )

- ↑ Currey, L.W. Science Fiction and Fantasy Authors: A Bibliography of First Printings of Their Fiction. G. K. Hall, 1978.

- ↑ "Remembering Science Fiction Author Frank Herbert: Highlighting His Archives In the Pollak Library". California State University, Fullerton. February 27, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2014.

- ↑ "Dune: Book to Screen Timeline". Duneinfo.com. Retrieved January 18, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Jodorowsky, Alejandro (1985). "Dune: Le Film Que Vous Ne Verrez Jamais (Dune: The Film You Will Never See)". Métal Hurlant. DuneInfo.com. Retrieved February 8, 2014.

- ↑ Chris Cutler, book included with Henry Cow 40th Anniversary CD box set (2008)

- ↑ Falk, Gaby (ed). HR GIGER Arh+. Taschen, 2001, p.52

- ↑ Cinefantastique, September 1984 (Vol 14, No 4 & 5 - Double issue).

- ↑ Rozen, Leah (June 25, 1984). "With Another Best-Seller and An Upcoming Film, Dune Is Busting Out All Over For Frank Herbert". People.com. People Vol. 21, No. 25. pp. 129–130. Retrieved March 21, 2010.

- ↑ Feeney, Mark. "Screen of dreams." The Boston Globe. (16 December 2007) p. N12.

- ↑ Kevin J. Anderson Interview ~ DigitalWebbing.com (2004) Internet Archive, July 3, 2007.

- 1 2 3 Siegel, Tatiana (2008-03-17). "Berg to direct Dune for Paramount". Variety. Retrieved 2008-04-03.

- ↑ "New Dune Film from Paramount.". DuneNovels.com. 2008-03-18. Archived from the original on 2008-04-09. Retrieved 2008-04-03.

- ↑ Neuman, Clayton (August 17, 2009). "Winds of Dune Author Brian Herbert on Flipping the Myth of Jihad". AMCtv.com. Retrieved August 19, 2009.

- ↑ Roush, George (December 1, 2009). "Special Preview: El Guapo Spends A Day On A Navy Destroyer For Peter Berg's Battleship!". LatinoReview.com. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ↑ Rowles, Dustin (October 27, 2009). "Pajiba Exclusive: An Update on the Dune Remake". Pajiba.com. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ↑ Sperling, Nicole (January 4, 2010). "Dune remake back on track with director Pierre Morel". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ↑ "Dune" Remake Lands New Screenwriter, Screen Crave, February 11, 2010

- ↑ Fleming, Mike (November 8, 2010). "Sands of Time Running Out For New Dune". Deadline.com. Retrieved December 27, 2010.

- ↑ Reynolds, Simon (March 23, 2011). "Dune remake dropped by Paramount". Digital Spy. Retrieved 2011-03-24.

- ↑ Busch, Anita (November 21, 2016). "Legendary Acquires Frank Herbert's Classic Sci-Fi Novel Dune For Film And TV". Deadline.com. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- ↑ Kroll, Justin (November 21, 2016). "Legendary Lands Rights to Classic Sci-Fi Novel Dune". Variety. Retrieved November 27, 2016.

- ↑ Roberts, Adam (2000). Science Fiction. New York: Routledge. pp. 85–90. ISBN 0-415-19204-8.

- ↑ Weiner, Ellis. Doon. New York: Pocket, 1984.

- ↑ Wall, Mick (2004). Iron Maiden: Run to the Hills, the Authorised Biography (3rd ed.). Sanctuary Publishing. p. 244. ISBN 1-86074-542-3.

- ↑ St. James Encyclopedia of Pop Culture by Craig T. Cobane Retrieved 12 July 2008.

- ↑ Has Dune inspired other music? - Stason.org Retrieved 12 July 2008.

- ↑ "Matthew Good Near Fantastica Lyrics". Justsomelyrics.com. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- ↑ "Golem lyrics and info: The 2nd Moon (1999)". Golem-metal.de. Retrieved July 10, 2009.

- ↑ Lowachee, Karin (2003). "Space, symbols, and synth-rock imbue the metaphoric musical world of 30 Seconds To Mars". Mars Dust. Mysterian Media. Archived from the original on 2006-10-22.

- ↑ "Re-Direct". Youngblood Brass Band. Retrieved 2012-08-29.

- ↑ Shah, Rawn; Romine, James (1995). Playing MUDs on the Internet. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 213. ISBN 0-471-11633-5.

- ↑ Herbert, Brian (2004). Dreamer of Dune: The Biography of Frank Herbert. p. 244.

- ↑ "Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature: Dune on Moon". Planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov. Retrieved October 16, 2016.

Further reading

- Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1995). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 1386. ISBN 0-312-13486-X.

- Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1995). The Multimedia Encyclopedia of Science Fiction (CD-ROM). Danbury, CT: Grolier. ISBN 0-7172-3999-3.

- Nicholls, Peter (1979). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. St Albans, Herts, UK: Granada Publishing Ltd. p. 672. ISBN 0-586-05380-8.

- Jakubowski, Maxim; Edwards, Malcolm (1983). The Complete Book of Science Fiction and Fantasy Lists. St Albans, Herts, UK: Granada Publishing Ltd. p. 350. ISBN 0-586-05678-5.

- Pringle, David (1990). The Ultimate Guide to Science Fiction. London: Grafton Books Ltd. p. 407. ISBN 0-246-13635-9.

- Tuck, Donald H. (1974). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy. Chicago: Advent. p. 136. ISBN 0-911682-20-1.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Dune |

- Official website for Dune and its sequels

- Dune title listing at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Interviewer: Paul Turner (October 1973). "Vertex Interviews Frank Herbert". Volume 1, Issue 4.

- Dune audiobooks ~ collection of audiobooks on the Dune series

- Spark Notes: Dune, detailed study guide

- Audio Review at The Science Fiction Book Review Podcast

- DuneQuotes.com - Collection of quotes from the Dune series

- Dune by Frank Herbert, reviewed by Ted Gioia (Conceptual Fiction)

- "Frank Herbert Biography and Bibliography at LitWeb.net". www.litweb.net. Archived from the original on April 2, 2009. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- "Arabic and Islamic themes in Frank Herbert's Dune". The Baheyeldin Dynasty. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- Works of Frank Herbert at DMOZ

- Timberg, Scott (April 18, 2010). "Frank Herbert's Dune holds timely—and timeless—appeal". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- Walton, Jo (January 12, 2011). "In league with the future: Frank Herbert's Dune (Review)". Tor.com. Retrieved November 27, 2013.

- Leonard, Andrew (June 4, 2015). "To Save California, Read Dune". Nautilus. Retrieved June 15, 2015.