Economic ideology

| Economic ideologies |

|---|

|

Anarchist · Capitalist Communist · Corporatist Democratic · Dirigist Distributist · Fascist · Georgist Islamic · Laissez-faire Market socialist · Mutualist (Neo-) Mercantilist · Participatory Protectionist · Socialist Syndicalist · Third Way |

|

Business and economics portal |

An economic ideology distinguishes itself from economic theory in being normative rather than just explanatory in its approach. It expresses a perspective on the way an economy should run and to what end, whereas the aim of economic theories is to create accurate explanatory models. However the two are closely interrelated as underlying economic ideology influences the methodology and theory employed in analysis. The diverse ideology and methodology of the 74 Nobel laureates in economics speaks to such interrelation.[1]

A good way of discerning whether an ideology can be classified an economic ideology is to query if it inherently takes a specific and detailed economic standpoint. For instance, Anarchism cannot be said to be an economic ideology as such, because it has amongst others Anarcho-capitalism on the one hand and Anarcho-communism on the other as subcategories thereof, which are in themselves opposing ideological standpoints.

Furthermore, economic ideology is distinct from an economic system that it supports, such as a capitalist ideology, to the extent that explaining an economic system (positive economics) is distinct from advocating it (normative economics).[2] The theory of economic ideology explains its occurrence, evolution, and relation to an economy[3]

Examples

| Economics |

|---|

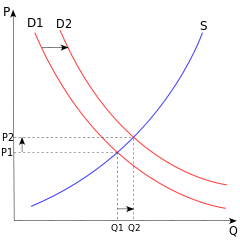

Supply and Demand graph, illustrating one of the most important economic principles |

|

|

| By application |

|

| Lists |

|

Capitalism

Capitalism is a broad economic system where the means of production are largely or entirely privately owned and operated for profit, where the allocation of capital goods is determined by capital markets and financial markets.

There are several implementations of capitalism that are loosely based around how much government involvement or public enterprise exists. The main ones that exist today are mixed economies, where the state intervenes in market activity and provides some services; Laissez faire, where the state only supplies a court, a military, and a police; and state capitalism, where the state engages in commercial business activity itself.

Laissez-faire

Laissez-faire, or free market capitalism, is an ideology that prescribes minimal public enterprise and government regulation in a capitalist economy. This ideology advocates for a type of capitalism based on open competition to determine the price, production and consumption of goods through the invisible hand of supply and demand reaching efficient market equilibrium. In such a system, Capital, property and enterprise are entirely privately owned and new enterprises may freely gain market entry without restriction. Employment and wages are determined by a labour market that will result in some unemployment. Government and Judicial intervention are employed at times to change the economic incentives for people for various reasons. The capitalist economy will likely follow a business cycle of economic growth along with a steady cycle of small booms and busts.

Social market

The social market economy (also known as Rhine capitalism) is advocated by the ideology of ordoliberalism and social liberalism. This ideology supports a free-market economy where supply and demand determine the price of goods and services, and where markets are free from regulation. However this economic ideology calls for state action in the form of social policy favoring social insurance, unemployment benefits and recognition of labor rights.

Socialism

Socialism refers to the various theories of economic organization based on some form of social ownership of the means of production and cooperative management of the allocation of resources. Socialist systems can be distinguished by the dominant coordination mechanism employed (economic planning or markets) and by the type of ownership employed (Public ownership or cooperatives).

In some models of socialism (often called market socialism), the state approves of the prices and products produced in the economy, subjecting the market system to direct external regulations. Alternatively, the state may produce the goods but then sell them in competitive markets.[4]

Democratic socialism

Democratic socialism (sometimes referred to as economic democracy) is an economic ideology that calls for democratic institutions in the economy. These may take the form of cooperatives, workplace democracy or ad hoc approach to the management and ownership of the means of production.

Marxism-Leninism

Marxism-Leninism is a political ideology that calls for centralized planning of the economy. This ideology formed the economic basis of all existing Communist states.

A socialist state will primarily concern itself with the welfare of its citizens. Socialist doctrines essentially promote the collectivist idea that an economy's resources should be used in the interest all participants, and not simply for private gain. This notion historically alienated the market economy, and tended to favor central planning. Countries that favored excessive central controls experienced economic decline and collapse in the long run, as was the case with the Soviet Union.[5]

Communism

As Friedrich Engels described it (in Anti-Dühring), communism is the evolution of socialism so that the central role of the State has 'withered away' and is no longer necessary for the functioning of a planned economy. All property and capital are collectively owned and managed in a communal, classless and egalitarian society. Currency is no longer needed, and all economic activity, enterprise, labour, production and consumption is freely exchanged "from each according to his ability, to each according to his needs".

Communism is also a political system as much an economic one—with various models in how it is implemented—the well known being the Marxist Leninist model, which argues for the use of a vanguard party to bring about a workers state to be used as a transitional tool to bring about stateless communism, the economic arrangement described above. Other models to bring about communism include democratic socialism, which argues for slow social transformation and evolution, or anarcho-communism, which argues similarly to Marxist schools for a revolutionary transformation to the above economic arrangement, but does not use a transitional period or vanguard party.

See also

- Constitutional economics

- Economic system

- Development economics

- Ecological economics

- Political economy

- Social model

- Political ideology

Notes

- ↑ "Ideological Profiles of the Economic Laureates". Econ Journal Watch. 10 (3): 255-682. 2013.

- ↑ Kurt Klappholz, 1987. "ideology," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 2, p. 716.

- ↑ • Roland Bénabou, 2008. "Ideology," Journal of the European Economic Association, 6(2-3), pp. 321-352.

• Joseph P. Kalt and Mark A. Zupan, 1984. "Capture and Ideology in the Economic Theory of Politics," American Economic Review, 74(3), p p. 279-300. Reprinted in C. Grafton and A. Permaloff, ed., 2005, The Behavioral Study of Political Ideology and Public Policy Formation, ch. 4, pp. 65-104. - ↑ Schleifer, Andrei, and Robert W. Vishny. "The Politics of Market Socialism." Journal of Economic Perspectives 8.2 (1994): 165-76. Print. http://scholar.harvard.edu/files/shleifer/files/politics_market_socialism.pdf

- ↑ "socialism." A Dictionary of Economics (3 ed.). Oxford Reference, 2009. Web. 8 July 2013. http://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780199237043.001.0001/acref-9780199237043-e-2896?rskey=7j98WR&result=2743&q=

References

- Karl Brunner, 1996. Economic Analysis and Political Ideology: The Selected Essays of Karl Brunner, v. 1, Thomas Ly, ed. Chapter-preview links via scroll down.

- Kurt Klappholz, 1987. "ideology," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 2, pp. 716–18.

- From The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. 2008, 2nd Edition:

- "capitalism" by Robert L. Heilbroner. Abstract.

- "contemporary capitalism" by William Lazonick. Abstract.

- "Maoist economics" by Wei Li. Abstract.

- "social democracy" by Ben Jackson. Abstract.

- "welfare state" by Assar Lindbeck. Abstract.

- "American exceptionalism" by Louise C. Keely.Abstract.

- "laissez-faire, economists and" by Roger E. Backhouse and Steven G. Medema. Abstract.

- Julie A. Nelson and Steven M. Sheffrin, 1991. "Economic Literacy or Economic Ideology?" Journal of Economic Perspectives, 5(3), pp. 157-165 (press +).

- Joseph A. Schumpeter, 1942. Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy.

- _____, 1949. "Science and Ideology," American Economic Review, 39(2), pp. 346–359. Reprinted in Daniel M. Hausman, 1994, 2nd rev. ed., The Philosophy of Economics: An Anthology, Cambridge University Press, pp. 224-238.

- Robert M. Solow, 1971. ""Science and Economic Ideology," The Public Interest, 23(1) pp. 94–107. Reprinted in Daniel M. Hausman, 1994, 2nd rev. ed., The Philosophy of Economics: An Anthology, Cambridge University Press, pp. 239-251.

- Karl Marx, 1857-58. "Ideology and Method in Political Economy," in Grundrisse: Foundation of the Critique of Political Economy, tr. 1973. Reprinted in Daniel M. Hausman, 1994, 2nd rev. ed., The Philosophy of Economics: An Anthology, Cambridge University Press, pp. 119-142.

- Earl A. Thompson and Charles Robert Hickson, 2000. Ideology and the Evolution of Vital Economic Institutions. Springer.Descrip;tion and chapter preview links, pp. vii-x.