Parliament of Finland

| Parliament of Finland Suomen eduskunta Finlands riksdag | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Leadership | |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 200 |

| |

Political groups |

Governing coalition (124)

Opposition parties (76)

|

| Elections | |

| Electoral district proportional representation | |

Last election | 19 April 2015 |

Next election | April 2019 or earlier |

| Meeting place | |

| |

|

Eduskuntatalo Mannerheimintie 30 FI-00102 Helsinki, Republic of Finland | |

| Website | |

| www.eduskunta.fi www.riksdagen.fi | |

The Eduskunta (Finnish: eduskunta or Suomen eduskunta, Swedish: riksdagen or Finlands riksdag) is the parliament of Finland. The unicameral parliament has 200 members and normally meets in the Parliament House in Helsinki. However, during the 2015–2017 renovation of the Parliament House, the parliament temporary meets in the nearby Sibelius Academy.[1] The latest election to the parliament took place on April 19, 2015.

Constitution

Under the Constitution of Finland, the 200-member unicameral parliament exercises supreme decision-making authority in Finland. Sovereignty belongs to the people and that power is vested in the parliament. It passes legislation, decides on the state budget, approves international treaties, and supervises the activities of the government. It may alter the constitution, bring about the resignation of the Council of State, and override presidential vetoes; its acts are not subject to judicial review. Legislation may be initiated by the Council of State, or one of the members of the Eduskunta. To make changes to the Constitution, amendments must be approved twice by the Eduskunta, in two successive electoral periods with a general election held in between.

Members of parliament enjoy parliamentary immunity: Without the parliament's approval, members may not be prosecuted for anything they say in session or otherwise do in the course of parliamentary proceedings, or be arrested or detained except for serious offences.

Parliamentary elections

The Eduskunta's 200 representatives are elected directly by secret ballot on the basis of proportional representation. The electoral period is four years. Elections previously took two days but as early voting became popular they are now conducted on one day, since 2011 the third Sunday in April.

Every citizen who is at least 18 years of age by the election date is entitled to vote in general elections. With certain exceptions, such as military personnel on active duty, high judicial officials, the President of the Republic, and persons under guardianship, any voter may also stand as a candidate for Parliament. All registered parties are entitled to nominate candidates; individual citizens and independent electoral organizations must be endorsed by a sufficient number of voters to qualify.

In parliamentary elections, Finland is divided into 13 electoral districts. The number of representatives returned by each district depends on the population. Åland is an exception in that it always elects one representative. The provincial state offices appoint an election board in each electoral district to prepare lists of candidates and to approve the election results. The Ministry of Justice is ultimately responsible for elections.

The President of Finland can call for an early election, in the constitution of 2000 upon the proposal of the Prime Minister, after consultations with the parliamentary groups while Parliament is in session. Prior to the new constitution the President had the power to do this independently. The President has called an early election eight times in Finnish history; however, this has not happened since 1975.[2]

There is no hard and fast election threshold to get a seat in Parliament. In large part due to this, it is nearly impossible for one party to win an outright majority. Since the first election in 1907, only one party has ever won a majority—in the election of 1916, when the Social Democrats won 103 seats. Since Finland gained independence in 1917, no party has won the 101 seats necessary for a majority. It is also very difficult for the socialist and non-socialist blocs to form a government on their own. Most Finnish governments in recent history have been coalitions between three or more parties, and many of them have been grand coalitions between socialist and non-socialist parties.

The seats for each electoral district are assigned according to the d'Hondt method. Electoral districts were originally based on the historical lääni division from 1634, but there have been several subsequent changes. Although there is no set election threshold, many electoral districts have lost population in recent decades, and some now elect as few as six representatives. This makes it harder for small parties to win MPs in these districts.[3] The current administration plans to deal with the problem by rearranging the electoral districts.[4]

Government formation

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Finland |

|

Legislative

|

|

|

The President consults the Speaker of Parliament and with representatives of the parliamentary groups about the formation of a new Council of State (Government). According to the constitution, the Eduskunta elects the Prime Minister, who is appointed to office by the President. Other ministers are appointed by the President on the Prime Minister’s proposal. While individual ministers are not appointed by the Eduskunta, they may be individually removed by a vote of no confidence. The government as a whole must also have the confidence of the Eduskunta and must resign on a vote of no confidence.

Before the Prime Minister is elected, the parliamentary groups negotiate on the political programme and composition of the Council of State. On the basis of the outcome of these negotiations, and after having consulted the Speaker of the Eduskunta and the parliamentary groups, the President informs the Eduskunta of the nominee for Prime Minister. The nominee is elected Prime Minister if this is supported by a majority of votes in the Eduskunta.

Sessions

The annual session of parliament generally begins in February and consists of two terms, the first from January until June, the second from September to December. At the start of an annual session, the nation’s political leaders and their guests attend a special worship service at Helsinki Cathedral, before the ceremonies continue at Parliament House, where the President formally opens the session.

On the first day of each annual session, the Eduskunta selects a speaker and two deputy speakers from among its members. This election is chaired by the senior member in terms of age. The members who are elected to serve as speaker and first deputy speaker and second deputy speaker take the following solemn oath before Parliament;

"I,..., affirm that in my office as Speaker I will to the best of my ability defend the rights of the people, Parliament and the government of Finland according to the Constitution."

Each annual session of Parliament the MPs elect Finland’s delegations to the Nordic Council and the Council of Europe. The parliament also elects five of its members to the bench of the High Court of Impeachment for the parliamentary term.

Committees

The Parliament has 16 standing committees. Most committees have 17 permanent members, but the Grand Committee, the Finance Committee and the Audit Committee have 25, 21 and 11 permanent members respectively. In addition the committees have a number of substitute members. On average each MP is a member of two committees.[5]

15 of the committees are special committees, while the Grand Committee deals with EU affairs, but also has a wider range of tasks (see the chapter below on legislation). The role of the Constitutional Law Committee is important, as Finland — unlike many other European countries — does not have a separate Constitutional Court. The Committee for the Future is also noteworthy, as it does not usually deal with bills, but instead assesses factors relating to future developments and gives statements to other committees on issues relating to the future outlooks of their respective fields of speciality.[5]

The chairmanships of the committees are currently divided between the parties so that the Centre Party chairs four committees, the Finns Party, the National Coalition Party and the Social Democratic Party each chair three committees, and the Left Alliance, the Green League and the Swedish People's Party each have the chairmanship of one committee.[6]

| Committee | Chair | Chair's party |

|---|---|---|

| Grand Committee | fi:Anne-Mari Virolainen | National Coalition Party |

| Constitutional Law Committee | fi:Annika Lapintie | Left Alliance |

| Foreign Affairs Committee | Antti Kaikkonen | Centre Party |

| Finance Committee | Timo Kalli | Centre Party |

| Audit Committee | Eero Heinäluoma | Social Democratic Party |

| Administration Committee | Pirkko Mattila | Finns Party |

| Legal Affairs Committee | fi:Kari Tolvanen | National Coalition Party |

| Transport and Communications Committee | fi:Ari Jalonen | Finns Party |

| Agriculture and Forestry Committee | fi:Jari Leppä | Centre Party |

| Defence Committee | Ilkka Kanerva | National Coalition Party |

| Education and Culture Committee | Tuomo Puumala | Centre Party |

| Social Affairs and Health Committee | Tuula Haatainen | Social Democratic Party |

| Commerce Committee | Kaj Turunen | Finns Party |

| Committee for the Future | Carl Haglund | Swedish People's Party |

| Employment and Equality Committee | Tarja Filatov | Social Democratic Party |

| Environment Committee | Satu Hassi | Green League |

Proceedings

Legislation

Most of the bills discussed in the parliament originate in the Government. However, any member or group of members may introduce a bill, but usually these will not pass the committee phase. A third way to propose legislation was introduced in 2012: citizens may deliver an initiative for the parliament's consideration, if the initiative gains 50,000 endorsements from eligible voters within a period of six months. When delivered to the parliament, the initiative is dealt with in the same way as any other bill.[7] Any bill introduced will be initially discussed on the floor of the parliament and after that, sent to the respective committee. If the bill concerns several areas of legislation, the primary committee will first ask the other committees for opinions. If there is any concern about the constitutionality of the bill, the opinion of the Constitutional Committee is always asked. The Constitutional Committee works in non-partisan manner and uses the most distinguished legal scholars as experts. If the committee considers the bill to have unconstitutional elements, the bill must either be passed as a constitutional change or changed to be in concordance with the constitution. In most cases, the latter route is chosen.

The bills receive their final form in the parliamentary committees. The committees work behind closed doors but their proceedings are publicized afterwards. Usually the committees hear experts from special interest groups and various authorities after which they formulate the necessary changes to the bill in question. If the committee does not agree, the members in minority may submit their own version of the bill.

The committee statement is discussed by the parliament in two consecutive sessions. In the first session, the parliament discusses the bill and prepares its final form. In the first part of handling, a general discussion of the bill is undertaken. After this, the parliament discusses individual points of the bill and chooses between the bill proposed by the committee, minority opinions and the eventual other forms the members submit during the discussion. If the parliament wishes to do so, it may during the general discussion of the first handling submit the bill to the Grand Committee for further formulation. The bill is also always treated by the Grand Committee if the parliament decides to adopt any other form than the final opinion of the committee. The committee then formulates its own version of the bill and submits this to the parliament which then adopts either its former version or the version of the Grand Committee. The committee statements are influential documents in that they often used by the courts as indicative of the legislator's intent.

In the second session, the final formulation of the bill is either passed or dismissed. If the bill entails a change in constitution, the second session takes place only after the next election unless the parliament decides to declare the matter to be urgent by a majority of five-sixths. In constitutional matters, the bills are passed by a majority of two-thirds. In other cases, the simple majority of votes given is enough.

International treaties requiring changes to legislation are accepted by a simple majority in a single session. Treaties requiring changes to the constitution or changing the borders of Finland require a qualified majority of two thirds.

European Union affairs

Like other members of the European Union, Finland has delegated much of its sovereignty to the Union. The matters belonging to the jurisdiction of the European Union are decided by the Council of the European Union and the European Parliament. However, while changes to European legislation are under preparation, the Finnish Parliament participates actively in formulating Finland's official position on these changes.

European Union matters handled by the Parliament usually become public after committee meetings, as the proceedings of the committees are public. However, if the case requires, the government may ask the Parliament for a secret handling of an EU matter. This is especially the case if the government does not want to reveal its position in the negotiations beforehand.

The EU-legislation under preparation is brought to the Grand Committee of the Finnish Parliament by the Finnish government when Finland has received notice of the proposal from the European Commission. The Grand Committee discusses the matter in camera, and if appropriate, requests opinions from the specialized committees of the Parliament. Both the Grand Committee and the specialized committees hear expert opinions while preparing their opinions. Finally, the Grand Committee formulates the Finnish opinion to the proposal. However, as an exception to the general rule, in matters concerning the external relations of the Union, the Finnish stance is formulated by the Committee for Foreign and Security Policy, instead of the Grand Committee.

The Finnish government is obligated by law to follow the parliamentary opinion when discussing the matter with the Commission and other member states. However, if the situation requires, the government may change the Finnish stance, but it is required to report such changes to the Parliament immediately.

After the European union has made a legislative decision which must be implemented in Finland by an Act of Parliament, the matter is brought back to the parliament as with usual legislation. However, in such case, the Finnish state is already obligated to pass a law fulfilling certain requirements, so the hands of Parliament are no longer free. Thus, the key stage in the parliamentary handling of EU legislation is the Grand Committee phase during the preparatory stage.[8]

Other matters

Every member of parliament has the right to ask the government written questions. The questions are answered in writing within 21 days by a minister responsible for the matter and do not cause any further discussion. Furthermore, the parliament has a questioning session from time to time. In these, the members are allowed to ask short verbal questions, which are answered by the responsible ministers and then discussed by the parliament.

Any group of twenty members may interpellate. The motion of censure may be for the whole government or any particular minister. The motion takes the form of a question that is replied to by the responsible minister. If the parliament decides to approve the motion of censure, the committee responsible for the matter in question formulates the motion, which is then passed by the parliament.

The government may decide to make a report to the parliament in any matter. After discussion the parliament may either accept the report or pass a motion of censure. A passed motion of censure will cause the government to fall.

Any group of 10 members may raise the question of the legality of the minister's official acts. If such question is raised, the Constitutional Committee will investigate the matter, using all the powers of police. After the final report of the committee, the parliament decides whether to charge the minister in the High Court of Impeachment. The criminal investigation of the Constitutional Committee may also be initiated by the Chancellor of Justice, Parliamentary Ombudsman or by any parliamentary committee. Similar proceedings may also be initiated against the Chancellor of Justice, Parliamentary Ombudsman or the judges of the supreme courts. The President of Finland may be also the target of a criminal investigation of the Constitutional Committee, but the parliament must accept the indictment by a majority of three-fourths and the charge must be treason, high treason or a crime against humanity.

Members

The 200 members of parliament enjoy a limited legal immunity: they may not be prevented from carrying out their work as members of parliament. They may be charged with crimes they have committed in office only if the parliament gives a permission to that end with a majority of five-sixths of given votes. For other crimes, they may be arrested or imprisoned only for crimes which carry a minimum punishment of six months in prison, unless the parliament gives permission to arrest the member.

The members receive a monthly salary of 5,860 euros, which is taxable. Those who have served 12 years, receive 6,300 euros. In addition, they receive tax-free compensation of expenses, and may travel for free within the country by train, bus or plane for purposes related to legislative work. Inside the capital region, they may freely use taxis.[9]

A member who is elected to the European Parliament must choose between the two parliaments because a "double mandate" is not permissible. On the other hand, the members may have any municipal positions of trust.

The members have an unlimited right to discuss the matters at hand. However, they must behave in a "solemn and dignified manner" and refrain from personal insults. If the member breaks against this rule in the session of parliament, they may be interrupted by the spokesman. Grave breaches of order may be punished by two weeks' suspension from office after the decision of parliament. If a member is convicted of an intentional crime for a term in prison or of an electoral crime to any punishment, the parliament may decide to dismiss the member if two thirds of the votes given are for dismissal.

Women make up 40 percent of the members, the second-highest in the industrialized world (behind only the Parliament of Sweden).

Ruling majority

Finland's proportional representation system encourages a multitude of political parties and has resulted in many coalition-cabinets. No single party has held an absolute majority of seats during independence.

After the parliamentary election of 2011 a six-party governing coalition was formed with Jyrki Katainen of the National Coalition Party as Prime Minister. Besides Katainen's party his coalition included the Social Democratic Party, the Left Alliance, the Green League, the Swedish People's Party and the Christian Democrats.

History

The Eduskunta was preceded by the Diet of Finland (Swedish: lantdagen; Finnish: maapäivät, later Finnish: valtiopäivät), which had succeeded the Riksdag of the Estates in 1809. When the unicameral Parliament of Finland was established by the Parliament Act in 1906, Finland was an autonomous Grand Duchy and Principality under the Imperial Russian Tsar/Czar, (of the Romanov dynasty ruling family) who ruled as the Grand Duke, rather than as an absolute monarch. Universal suffrage and eligibility was implemented first in Finland. Women could both vote and run for office as equals, and this applied also to landless people with no excluded minorities. The first election to the Parliament was arranged in 1907. The first Parliament had 19 female representatives, an unprecedented number at the time, which grew to 21 by 1913.[10]

The first steps of the new Parliament were difficult as between 1908–1916 the power of the Finnish Parliament was almost completely neutralized by the Russian Tsar/Czar Nicholas II and the so-called "sabre-senate" of Finland, a bureaucratic government formed by Imperial Russian Army officers, during the second period of "Russification". The Parliament was dissolved and new elections were held almost every year during the period. The Finnish Parliament received the true political power for the first time after the February Revolution (First Revolution) of 1917 in Russia.[11]

Finland declared its independence on December 6, 1917 and in the winter and spring of 1918 endured the tragic Finnish Civil War, in which the "Whites" (forces of the Senate) defeated the socialist "Reds". After the War, monarchists and republicans struggled over the country's form of government. The monarchists seemed to gain a victory when the Parliament elected a German prince as King of Finland in the Fall of 1918, since the other states of Scandinavia to the west were ruled by monarchs. However, this King-elect abdicated the throne after Imperial Germany's defeat in World War I on November 11, 1918, in the "Armistice" on the Western Front. In the parliamentary election of 1919 the republican parties won three quarters of the seats and thus the monarchists' ambitions were defeated. Finland became a republic with a parliamentary system, but in order to appease the monarchist parties favouring a strong head of state, extensive powers were reserved for the President of Finland. During the Winter war, the parliament temporarily moved to Kauhajoki.

The constitution of 1919, which instituted a parliamentary system, did not undergo any major changes for 70 years. Although the government was responsible to the parliament, the president wielded considerable authority, which was fully utilized especially by President Urho Kekkonen. As the constitution implemented very strong protections for political minorities, most changes in legislation and state finances could be blocked by a qualified minority of one third. This, in conjunction with the inability of some of the parties to enter into coalition governments, led to weak, short-lived cabinets. Only during President Mauno Koivisto's tenure in 1980's, cabinets sitting for the whole parliamentary term became the rule. At the same time, the ability of qualified minorities to block legislation was gradually removed and the powers of the parliament were greatly increased in the constitutional reform of 1991.

The new, revised constitution of 2000 removed almost all domestic powers of the president, strengthening the cabinet and the parliament. It also included the methods for the discussion of European Union legislation under preparation in the parliament.

In 1982 Members of Parliament made a law for themselves of partial pension at the age of 25 and full pension rights from the age of 33.[12]

Dissolvings of Parliament

| Date .[13] | Dissolver[13] | Reason[13] | New Elections [13] |

|---|---|---|---|

| April 6, 1908 | Czar Nicholas II | No confidence vote | Parliamentary election, 1908 |

| February 22, 1909 | Dispute over the Speaker P. E. Svinhufvud's opening speech | Parliamentary election, 1909 | |

| 18 November 1909 | dispute over military budjet contribution to the Imperial Russian Army | Parliamentary election, 1910 | |

| 8 October 1910 | dispute over military budjet contribution to the Imperial Russian Army and Non-Discrimination Act | Parliamentary election, 1911 | |

| 1913 | Parliamentary election, 1913 | ||

| 2 August 1917 | Provisional Government of Russia | Act of Power | Parliamentary election, 1917 |

| 23 December 1918 | Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim (State Regent) |

Hung parliament | Parliamentary election, 1919 |

| 18 January 1924 | K. J. Ståhlberg (President) |

Hung parliament | Parliamentary election, 1924, |

| 19 April 1929 | Lauri Kristian Relander | Government clerks payroll act voting | Parliamentary election, 1929 |

| 15 July 1930 | Bill over banning communist activity | Parliamentary election, 1930 | |

| 8 December 1953 | J. K. Paasikivi | Government cabinet crises | Parliamentary election, 1954 |

| 14 November 1961 | Urho Kekkonen | Note Crisis | Parliamentary election, 1962 |

| 29 October 1971 | Dispute over agricultural payroll | Parliamentary election, 1972 | |

| 4 June 1975 | dispute over developing area budjet | Parliamentary election, 1975 |

Parliament building

In 1923 a competition was held to choose a site for a new Parliament House. Arkadianmäki, a hill beside what is now Mannerheimintie, was chosen as the best site.

The architectural competition which was held in 1924 was won by the firm of Borg–Sirén–Åberg with a proposal called Oratoribus. Johan Sigfrid Sirén (1889–1961), who was mainly responsible for preparing the proposal, was given the task of designing Parliament House. The building was constructed 1926–1931 and was officially inaugurated on March 7, 1931.[14] Ever since then, and especially during the Winter War and Continuation War, it has been the scene of many key moments in the nation's political life.

Parliament House was designed in the classic style of the 1920s. The exterior is reddish Kalvola granite. The façade is lined by fourteen columns with Corinthian capitals. The first floor contains the main lobby, the Speaker’s reception rooms, the newspaper room, the Information Service, the Documents Office, the messenger centre, the copying room, and the restaurant and separate function rooms. At both ends of the lobby are marble staircases leading up to the fifth floor.

The second or main floor is centered around the Session Hall. Its galleries have seats for the public, the media and diplomats. Also located on this floor are the Hall of State, the Speaker’s Corridor, the Government’s Corridor, the cafeteria and adjacent function rooms.

The third floor includes facilities for the Information Unit and the media and provides direct access to the press gallery overlooking the Session Hall. The Minutes Office and a number of committee rooms are also located here.

The fourth floor is reserved for committees. Its largest rooms are the Grand Committee Room and the Finance Committee Room. The fifth floor contains meeting rooms and offices for the parliamentary groups. Additional offices for the parliamentary groups are located on the sixth floor, along with facilities for the media.

Notable later additions to the building are the library annex completed in 1978 and a separate office block, the need for which was the subject of some controversy, completed in 2004.[14]

The building is currently undergoing extensive renovations that started in 2007 and are expected to be ready in 2017 as Finland celebrates the centennial of her independence.

Major political parties

The Centre Party (Finnish: Suomen Keskusta, Kesk; Swedish: Centern i Finland) was the largest party in the 2015 election. It is an agrarian party, traditionally representing rural interests and dominating rural municipalities. Likewise, it received only one seat in Helsinki. The party is a member of the Liberal International and the European Liberal Democrat and Reform Party and subscribes to the liberal manifestos of these organisations. Its members in the European Parliament are members of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe.

The Finns Party (aka. True Finns) (Finnish: Perussuomalaiset; Swedish: Sannfinländarna) were the second largest party by seat count in the 2015 election. They are a populist and nationalist party, critical of the European Union. In the European Parliament they are a member of the European Conservatives and Reformists group.

The National Coalition Party (Finnish: Kansallinen Kokoomus, Kok; Swedish: Samlingspartiet) was the most popular party in the 2011 election, but finished as third in seats in the 2015 election. It is a liberal conservative party, and has been the most popular party for people in southern cities such as Helsinki. It is a member of the European People's Party, the largest European political party.

The Social Democratic Party of Finland (Finnish: Suomen Sosialidemokraattinen Puolue, SDP; Swedish: Finlands Socialdemokratiska Parti) is a social democratic party. It came fourth in the 2015 election, the worst electoral result in the party's history. The SDP is a member of the Party of European Socialists and Socialist International.

The Green League (Finnish: Vihreä Liitto; Swedish: Gröna förbundet) is a party based on green politics and social liberalism. The party does not admit to supporting traditional left-wing or right-wing policies as a matter of principle.

The Left Alliance (Finnish: Vasemmistoliitto; Swedish: Vänsterförbundet) is a democratic socialist party that, when founded in 1990, replaced several communist and taistoist (orthodox pro-Soviet communist) parties.

The Swedish People's Party (Swedish: Svenska folkpartiet (SFP); Finnish: Ruotsalainen kansanpuolue (RKP)) is a Swedish-speaking minority and centre-right liberal party. The party is a member of Liberal International and the European Liberal Democrat and Reform Party. The MP for Åland sits in the same parliamentary group with the SFP.

The Christian Democrats (Finnish: Kristillisdemokraatit, KD; Swedish: Kristdemokraterna) are a Christian democratic party.

Election result 2015

Result of the election held on April 19, 2015:

| Party | Votes | % | Seats | +/– |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Centre Party | 626,218 | 21.10 | 49 | +14 |

| Finns Party | 524,054 | 17.65 | 38 | –1 |

| National Coalition Party | 540,212 | 18.20 | 37 | –7 |

| Social Democratic Party | 490,102 | 16.51 | 34 | –8 |

| Green League | 253,102 | 8.53 | 15 | +5 |

| Left Alliance | 211,702 | 7.13 | 12 | –2 |

| Swedish People's Party of Finland | 144,802 | 4.88 | 9 | 0 |

| Christian Democrats | 105,134 | 3.54 | 5 | –1 |

| Åland Coalition | 10,910 | 0.37 | 1 | 0 |

| Pirate Party | 25,086 | 0.85 | 0 | 0 |

| Independence Party | 13,638 | 0.46 | 0 | 0 |

| Communist Party | 7,529 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 |

| Change 2011 | 7,442 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 |

| Pirkanmaa Joint List | 2,469 | 0.08 | 0 | New |

| Liberals for Åland | 1,277 | 0.04 | 0 | 0 |

| Communist Workers' Party | 1,100 | 0.04 | 0 | 0 |

| Workers' Party | 984 | 0.03 | 0 | 0 |

| For the Poor | 623 | 0.02 | 0 | 0 |

| Independents | 2,075 | 0.07 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 2,968,459 | 100 | 200 | 0 |

| Valid votes | 2,968,459 | 99.48 | ||

| Invalid/blank votes | 15,397 | 0.52 | ||

| Total votes cast | 2,983,856 | 100 | ||

| Registered voters in Finland/turnout in Finland | 4,221,237 | 70.1 | ||

| Registered voters overall/turnout overall | 4,463,333 | 66.9 | ||

| Source: Ministry of Justice, YLE | ||||

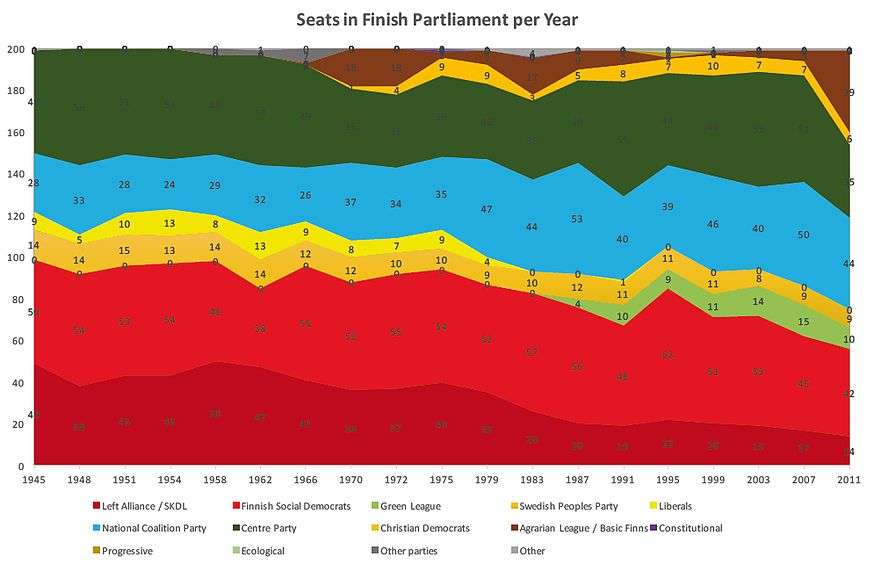

Election Results since 1945

|

|---|

See also

- List of members of the Parliament of Finland, 2015–19

- 2007 Finnish campaign finance scandal

- Parliament of Åland

- Politics of Finland

- List of political parties in Finland

References

- ↑ Tältä näyttää eduskunnan uusi istuntosali Sibelius-Akatemiassa – video, YLE 9 April 2015, accessed 24 May 2015.

- ↑ PL 64. "Vaalit 2007". yle.fi. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- ↑ "Vaalijärjestelmän kehittäminen esillä iltakoulussa". Vn.fi. 2002-05-15. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- ↑ "Vaaliuudistus kuopattiin lopullisesti | Kotimaan uutiset". Iltalehti.fi. 2011-10-07. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- 1 2 "Committees | Parliament of Finland". Web.eduskunta.fi. 2011-10-24. Retrieved 2011-11-28.

- ↑ "Suuren valiokunnan puheenjohtajuus kokoomukselle". verkkouutiset.fi. 2015-04-28. Retrieved 2015-04-28.

- ↑ https://www.kansalaisaloite.fi/fi

- ↑ EU-asiat eduskunnassa. Finnish Parliament. Retrieved 1 December 2008. (Finnish). The whole section is written on the basis of this reference.

- ↑ MPs' salaries and pensions. Finnish Parliament. Retrieved 15 June 2009. (English).

- ↑ "A Kansas Woman Runs for Congress". The Independent. Jul 13, 1914. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ↑ Apunen 1987, pp. 47–404

- ↑ Aarno Laitinen Musta monopoli Kustnnus vaihe Ky Gummerus 1982

- 1 2 3 4 Vaarnas, Kalle . Otavan Suuri Ensyklopedia. 1977.Eduskunta Osa 2 (Cid–Harvey) page 932. Otava.(Finnish)

- 1 2 "Parliament House". Parliament of Finland. Retrieved 25 January 2012.

- Apunen, Osmo (1987), Rajamaasta tasavallaksi. In: Blomstedt, Y. (ed.) Suomen historia 6, Sortokaudet ja itsenäistyminen, pp. 47–404. WSOY. ISBN 951-35-2495-7.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Parliament of Finland. |

- Parliament of Finland – official website

- History of the Finnish Parliament

- Findicator - Voting turnout in the Finnish Parliamentary Elections since 1908