Emirates Stadium

| |

| |

| Location |

Holloway London, N5 England |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 51°33′18″N 0°6′31″W / 51.55500°N 0.10861°WCoordinates: 51°33′18″N 0°6′31″W / 51.55500°N 0.10861°W |

| Public transit |

|

| Owner | Arsenal Holdings plc |

| Operator | Arsenal Holdings plc |

| Executive suites | 152 |

| Capacity | 60,432[1] |

| Record attendance | 60,161 (Arsenal vs Manchester United, 3 November 2007) |

| Field size | 105 × 68 metres |

| Surface | Desso GrassMaster |

| Construction | |

| Broke ground | February 2004 |

| Opened | 22 July 2006 |

| Construction cost | £390 million[2] |

| Architect | Populous[3] |

| Structural engineer | Buro Happold |

| Services engineer | Buro Happold |

| General contractor | Sir Robert McAlpine |

| Tenants | |

| Arsenal F.C. (2006–present) | |

The Emirates Stadium (known as Ashburton Grove prior to sponsorship, and as Arsenal Stadium for UEFA competitions) is a football stadium in Holloway, London, England, and the home of Arsenal Football Club. With a capacity of over 60,000, it is the third-largest football stadium in England after Wembley and Old Trafford.

In 1997, Arsenal explored the possibility of relocating to a new stadium, having been denied planning permission by Islington Council to expand its home ground of Highbury. After considering various options (including purchasing Wembley Stadium), the club bought an industrial and waste disposal estate in Ashburton Grove in 2000. A year later they won the council's approval to build a stadium on the site; manager Arsène Wenger described this as the "biggest decision in Arsenal's history" since the board appointed Herbert Chapman.[4] Relocation began in 2002, but financial difficulties delayed work until February 2004. Emirates Airlines was later announced as the main sponsor for the stadium. The whole stadium project was completed in 2006 at a cost of £390 million.[2] The related Highbury Square development was completed in 2009 for an additional £130 million.[5][6]

The stadium has undergone a process of "Arsenalisation" since 2009 with the aim of restoring Arsenal's heritage and history. The ground has hosted international fixtures and music concerts.

History

Origin

In response to the Hillsborough disaster of April 1989, an inquiry led by Lord Taylor of Gosforth was launched into crowd safety at sports grounds.[7] Finalised in January 1990, the Taylor Report recommended terraces (standing areas) be replaced by seating.[8] Many football clubs, faced with the requirement of making their grounds all-seater by the start of the 1994–95 season, had sought ways of raising income for converted terraced areas.[9] Arsenal at the end of the 1990–91 season introduced a bond scheme, which offered supporters the right to buy a season ticket at its renovated North Bank stand of Highbury.[9][10] The board felt this was the only viable option after considering other proposals; they did not want to compromise on their traditions, nor limit manager George Graham's resources.[11] At a price of between £1,000 to £1,500, the 150-year bond was criticised by supporters, who argued it potentially blocked the participation of those less well-off from supporting Arsenal.[12] A campaign directed by the Independent Arsenal Supporters' Association brought relative success as only a third of all bonds were sold.[13]

The North Bank was the last area of Highbury to be refurbished. It opened in August 1993 at a cost of £20 million.[14] The rework significantly reduced the stadium's capacity, from 57,000 at the beginning of the decade to under 40,000.[15] High ticket prices to serve the club's existing debts and low attendance figures forced Arsenal to explore the possibility of building a larger stadium in 1997. The club wanted to attract an evergrowing fanbase and financially compete with the biggest clubs in England.[15][16] Manchester United by comparison enjoyed a rise in gate receipts from £43.9 million in 1994 to £87.9 million in 1997, because of Old Trafford's expansion.[17]

Arsenal's initial proposal to rebuild Highbury was met with disapproval from local residents, as it required the demolition of 25 neighbouring houses.[18] It soon became problematic once the East Stand of the stadium was granted Grade II listing in July 1997.[19] After much consultation, the club eventually abandoned its plan, deciding a capacity of 48,000 was not big enough.[20]

In January 1998, Arsenal investigated the opportunity of relocating to Wembley Stadium and made an official bid to buy the ground two months later. However, the Football Association and the English National Stadium Trust opposed Arsenal's offer, stating that it would harm England's bid for the 2006 FIFA World Cup, though FIFA denied this.[21][22] By the end of the 1997–98 season, the bid was withdrawn and Wembley was purchased by The Football Association.[20] The stadium, however, played host to all of Arsenal's UEFA Champions League home ties during the 1998–99 and 1999–2000 seasons. Although the club fared poorly in the competition – eliminated twice from the group stages in successive seasons – Arsenal's record home attendance (73,707 against RC Lens in November 1998) was set and earned up to £1 million for each Wembley matchday, highlighting potential profitability.[23]

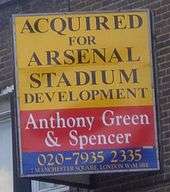

Site chosen and conflict

Through the persuasion of estate agent and club property adviser Antony Spencer, Arsenal examined the feasibility of building a new stadium in Ashburton Grove in November 1999.[20] The land, 500 yards (460 m) from Highbury, composed of a rubbish processing plant and industrial estate, 80% owned by the Islington Council, Railtrack and Sainsbury's.[24] The move therefore depended on the club buying out the existing occupants and financing for their relocation. After passing the first significant milestone at the council's planning committee, Arsenal submitted their planning application for a new 60,000 seater stadium in November 2000.[20][25] This included a redevelopment project at Drayton Park, converting the existing ground Highbury as flats and building a new waste station in Lough Road.[20] The scheme also involved the club creating 1,800 new jobs for the community and 2,300 new homes.[26][27] Improvements to three railway stations, Holloway Road, Drayton Park and Finsbury Park, were promised in order to cope with the matchday crowds.[27]

The move to Ashburton Grove was opposed by members of the Arsenal Independent Supporters' Association (AISA), who were concerned about environmental issues.[25] The Islington Stadium Communities Alliance (ISCA); an alliance of 16 groups representing local residents and businesses was set up in January 2000 to promote awareness against the redevelopment.[28] Alison Carmichael, a spokeswoman for the group said of the move: "It may look like Arsenal are doing great things for the area, but in its detail the plan is awful. We blame the council; the football club just wants to expand to make more money."[29] Seven months after the planning application was submitted in June 2001, a poll showed that 75% of respondents were against the scheme, with 2,133 residents objecting and 712 in support.[29] By October 2001, the club asserted that a poll of Islington residents found that 70% were in favour,[30] and received the backing from Mayor of London, Ken Livingstone.[31]

To push for more local support, the club planted the slogan "Let Arsenal support Islington" around Highbury during matches against Aston Villa and Juventus in December 2001.[32][33] It also featured as a backdrop for manager Arsène Wenger's press conference in the lead up to Christmas.[34] Islington Council approved Arsenal's plans on 10 December 2001, as 34 councillors voted in favour of the Ashburton Grove development with seven against and one abstention.[35] 31 voted for the transfer of a waste recycling plant in Lough Road and eight against.[35] The final vote was ratified by Ken Livingstone and Transport Secretary Stephen Byers.[36] Arsenal was given the all clear to start work in July 2002 after a High Court judge rejected a challenge by local residents and ISCA.[37] The club succeeded in a further legal challenge by small firms in January 2005 as the High Court upheld a decision by Deputy Prime Minister John Prescott to grant a compulsory purchase order in support of the scheme.[38]

The stadium became a major issue in the local elections in May 2006. The Metropolitan Police demanded that supporters' coaches be parked in the nearby Sobel Sports Centre rather than in the underground car park, and restrictions on access to 14 streets be imposed on match days. The health and safety certificate would not be issued unless the stadium meets such conditions, without which the stadium could not open. The road closures were passed at a council meeting, but kept under review.[39]

Finance and naming

Financing for the project proved difficult as Arsenal was not granted any public subsidy by the government. The club therefore sought other ways to generate income, namely by adopting a policy of buying football players for low transfer fees and selling high, as well as agreeing sponsorship deals. Arsenal recouped over £50 million from transfers involving Nicolas Anelka to Real Madrid and Marc Overmars, in a joint deal with Emmanuel Petit to Barcelona.[40] The transfer of Anelka in particular helped fund the club's new training ground, in London Colney, which opened in October 1999.[41]

In September 2000, Granada Media Group purchased a five-percent stake in Arsenal at a price of £47 million.[42] As part of the acquisition, Granada became the premier media agent for the football club, handling advertising, sponsorship, merchandising, publishing and licensing agreements.[42] The company furthermore invested £20 million in a joint venture, AFC Broadband, to exploit the club's internet viewership.[43] Arsenal chairman Peter Hill-Wood said of the deal: "This partnership will assist us in meeting Arsenal's two strategic objectives. First, to build a world-class team and a new stadium with an increased capacity so that more of our fans can enjoy watching the team. Secondly, to develop the Arsenal brand on a global basis by extending our fanbase around the world."[44] Managing Director Keith Edelman added that the investment would be used directly to fund for the new stadium.[42] The collapse of ITV Digital – part-owned by Granada – in April 2002 coincided with company being tied in to pay £30 million once arrangements for the new stadium were finalised.[45][46]

After announcing pre-tax loss of £22.3m for the financial year 2001–02, the club formulated plans to reduce their wage bills in order to continue with the stadium work.[47] Investment bank NM Rothschild and Sons was appointed to examine the financial situation at the club and advise whether it was feasible for Arsenal to move on with construction at the end of March 2003.[48] Although Arsenal secured a £260 million loan from a group of banks led by the Royal Bank of Scotland in April 2003, the club suspended work on Ashburton Grove citing in a statement, "We have experienced a number of delays in arrangements for our new stadium project in recent months across a range of issues. The impact of these delays is that we will now be unable to deliver a stadium opening for the start of the 2005–06 season."[45][49] The cost of building the stadium, forecasted at £400 million, had risen by a £100 million during that period.[50] To combat the financial difficulties, Arsenal throughout the summer of 2003 gave fans the opportunity to register their interest in a relaunched bond scheme.[51] The club planned to issue 3,000 bonds for between £3,500 and £5,000 each for a season ticket at Highbury, then at Ashburton Grove.[45] Arsenal supporters reacted with surprise to the reintroduction of the bond scheme with AISA chairman Steven Powell adding: "We are disappointed that the club has not consulted supporters before announcing a new bond scheme."[52] Though they never stated how many bonds were sold, Arsenal did raise several million pounds through the scheme.[45]

Sportswear provider Nike signed a contract extension with Arsenal in August 2003 to remain as the club's official kit supplier.[53] This was presented as a solution to the stadium financing; in addition to paying £55 million over seven years, Nike paid a minimum of £1 million each year as a royalty fee, dependent on sales.[54] On 23 February 2004, Arsenal Holdings plc – the club's parent company announced that funding for the stadium was now secured with construction work being able to resume.[55] Wenger said of the announcement: "It has been a big target of mine to participate in pushing the club forward and relocating to a new stadium is a necessity as it will enable us to become of one the biggest clubs in the world."[56] Interest on the £260 million debt was set at a commercial fixed rate over a 14-year period.[56] To refinance the cost, the club planned to convert the money into a 30-year bond financed by banks.[57] The proposed bond issue went ahead on 13 July 2006. Arsenal issued £210 million worth of 13.5-year bonds with a spread of 52 basis points over government bonds and £50 million of 7.1-year bonds with a spread of 22 basis points over LIBOR. It was the first publicly marketed, asset-backed bond issue by a European football club.[58] The effective interest rate on these bonds is 5.14% and 5.97%, respectively, and are due to be paid back over a 25-year period; the move to bonds has reduced the club's annual debt service cost to approximately £20 million a year.[59] In September 2010, Arsenal announced that the Highbury Square development – one of the main sources of income to reduce the stadium debt – was now debt free and making revenue.[60]

On 5 October 2004, Emirates Airline signed a 15-year contract with Arsenal estimated at £100 million.[61] Under the deal, the group secured naming rights to the stadium and shirt sponsorship when the club's deal with O2 expired at the end of the 2005–06 season.[61] The stadium name is often colloquially shortened from "Emirates Stadium" to "The Emirates", although some supporters continue to use the former name "Ashburton Grove" or even "The Grove" for the new stadium, especially those who object to the concept of corporate sponsorship of stadium names.[62] Due to UEFA regulations on stadium sponsors, during European matches the stadium is not officially referred to as Emirates Stadium, as Emirates are not an official sponsor of the Champions League competition; other stadia, such as the Allianz Arena in Munich, have fallen foul of this rule before.[63] UEFA refer to the stadium as Arsenal Stadium, which was the official name of the stadium at Highbury.[64]

In November 2012, Arsenal and Emirates officially announced a new deal worth £150 million at the Emirates Stadium. The partnership keeps Emirates as the official match and training shirt sponsor for another 5 years. The deal also grants Emirates the Ashburton Grove stadium naming rights until 2028. The deals payment terms were brought forward for potential earlier investment though the extent of this was not released.[65]

Construction and opening

Actual construction of the stadium began in February 2004. Arsenal appointed Sir Robert McAlpine in January 2002 to carry out building work and the stadium was designed by HOK Sport (known as Populous since 2009), who were the architects for Stadium Australia and the redevelopment of Ascot Racecourse.[66] Construction consultants Arcadis and engineering firm Buro Happold were also involved in the process.[67][68]

The first phase of demolition was completed in March 2004 and two months later stand piling on the West, East and North stands had been concluded.[69] Two bridges over the Northern City railway line connecting the stadium with Drayton Park were also built; these were completed in August 2004.[69] The stadium topped out in August 2005 and external glazing, power and water tank installation was completed by December 2005.[69] The first seat in the new stadium was ceremonially installed on 13 March 2006 by Arsenal midfielder Abou Diaby.[70] Like Highbury, DD GrassMaster was selected as the pitch installer with Hewitt Sportsturf contracted to design and construct the playing field.[71] Floodlights were successfully tested for the first time on 25 June 2006, and a day later the goalposts were erected.[72]

In order to obtain the licences the stadium needed to open, the stadium hosted three non-full capacity events. The first 'ramp-up' event was a shareholder open day on 18 July 2006, the second an open training session for 20,000 selected club members held two days later.[73][74] The third event on 22 July 2006 was striker Dennis Bergkamp's testimonial match against Ajax.[75]

The Emirates Stadium was officially opened by Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh on 26 October 2006; it had been intended that Queen Elizabeth II would open the stadium as well, but she suffered a back injury and was unable to attend on the day.[76] Prince Philip quipped with the crowd: "Well, you may not have my wife, but you've got the second-most experienced plaque unveiler in the world."[77] The royal visit echoed the attendance of the Queen's uncle, the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VIII) at the official opening of Highbury's West Stand in 1932.[78] As a result of the change of plan, Queen Elizabeth extended to the club the honour of inviting the chairman, manager and first team to join her for afternoon tea at Buckingham Palace on 15 February 2007 – the first club to be invited to the palace for such an event.[79]

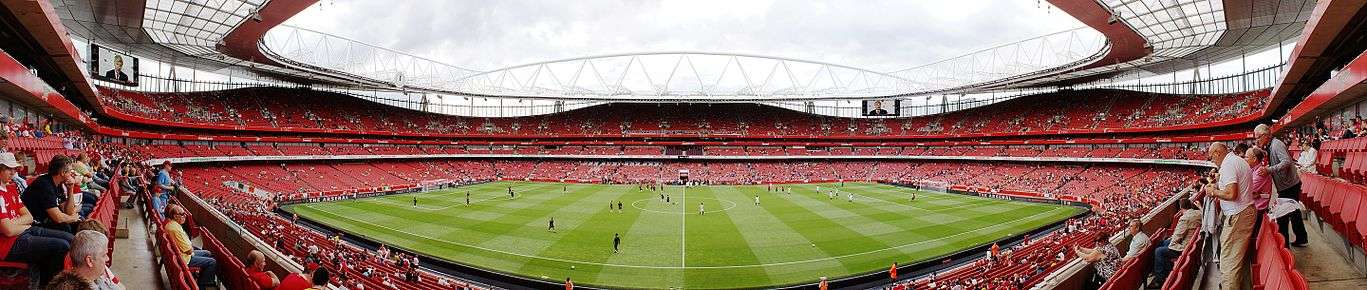

Design

The Emirates Stadium is seen by many as the benchmark for top league stadia developments in the UK and Europe. Its design is a radical break from the traditions of the "English style" stadia of the United Kingdom and the Municipal multi-tenant stadia of Europe. The focus on spectator experience for both general spectator and the Corporate or Premium Hospitality spectators marked a step change in stadia design and consequently on the football business in the UK, with Arsenal increasing their matchday revenues by 111%.[80] The architect, Christopher Lee of Populous, described the design as beautiful and intimidating.[81]

The Emirates Stadium is a three-tiered bowl with translucent polycarbonate roofing over the stands but not over the pitch.[82] The underside is clad with metallic panels and the roof is supported by four triangular trusses, made of welded tubular steel.[82] Two trusses span 200 metres (660 ft) in a north–south direction while a further two span an east–west direction.[82] The trusses are supported by the stadium's vertical concrete cores, eight of which connected to them by steel tripods. They in turn each house four stairways, a passenger lift as well as service access.[82] Façades are either glazed or woven between the cores which allows visitors on the podium to see inside the stadium.[82] The glass and steel construction was devised by Populous to give an impression that the stadium sparkles in sunlight and glows in the night.[82]

The upper (26,646) and lower (24,425) parts of the stadium feature standard seating. The stadium has two levels below ground that house its support facilities such as commercial kitchens, changing rooms and press and education centres.[82] The main middle tier, known as the "Club Level", is premium priced and also includes the director's box. There are 7,139 seats at this level, which are sold on licences lasting from one to four years. Immediately above the club tier there is a small circle consisting of 150 boxes of 10, 12 and 15 seats. The total number of spectators at this level is 2,222. The high demand for tickets, as well as the relative wealth of their London fans, means revenue from premium seating and corporate boxes is nearly as high as the revenue from the entire stadium at Highbury.[83]

The upper tier is contoured to leave open space in the corners of the ground, and the roof is significantly canted inwards. Both of these features are meant to provide as much airflow and sunlight to the pitch as possible.[84] The stadium also gives an illusion that supporters in the upper tier on one side of the ground are unable to see supporters in the upper tier opposite.[82] As part of a deal with Sony, the stadium was the first in the world to incorporate HDTV streaming.[85] In the north-west and south-east corners of the stadium are two giant screens suspended from the roof.

The pitch is 105 by 68 metres (115 by 74 yd) in size and the total grass area at Emirates is 113 by 76 metres (124 by 83 yd).[84] Like Highbury, it runs north–south, with the players' tunnel and the dugouts on the west side of the pitch underneath the main TV camera. The away fans are found in the south-east corner of the lower tier. The away supporter configuration can be expanded from 1,500 seats to 4,500 seats behind the south goal in the lower tier, and a further 4,500 seats can be made available also in the upper tier, bringing the total to 9,000 supporters (the regulation 15% required for domestic cup competitions such as the FA Cup and League Cup).[86]

The Emirates Stadium pays tribute to Arsenal's former home, Highbury. The club's offices are officially called Highbury House, located north-east of Emirates Stadium, and house the bust of Herbert Chapman that used to reside at Highbury. Three other busts that used to reside at Highbury of Claude Ferrier (architect of Highbury's East stand), Denis Hill-Wood (former Arsenal chairman) and manager Arsène Wenger have also been moved to Emirates Stadium and are in display in the entrance of the Diamond Club.[87] Additionally, the two bridges over the railway line to the east of the stadium, connecting the stadium to Drayton Park, are called the Clock End and North Bank bridges, after the stands at Highbury; the clock that gave its name to the old Clock End has been resited on the new clock end which features a newer, larger replica of the clock. The Arsenal club museum, which was formerly held in the North Bank Stand, opened in October 2006 and is located to the north of the stadium, within the Northern Triangle building. It houses the marble statues that were once held in the marble halls of Highbury.[88]

Arsenalisation

In August 2009, Arsenal began a programme of "Arsenalisation" of the Emirates Stadium after listening to feedback from supporters in a forum.[89] The intention was to turn the stadium into a "visible stronghold of all things Arsenal through a variety of artistic and creative means", led by club CEO Ivan Gazidis.[90]

Among the first changes were white seats installed in the pattern of the club's trademark cannon, located in the lower level stands opposite the entrance tunnel.[90] "The Spirit of Highbury" – a shrine depicting every player to have played for Arsenal during its 93-year residence – was erected in late 2009 outside the stadium at the south end.[91] Eight large murals on the exterior of the stadium were installed, each depicting four Arsenal legends linking arms, such that the effect of the completed design is 32 legends in a huddle embracing the stadium:[92]

Around the lower concourse of the stadium, further murals depicting 12 "greatest moments" in Arsenal history voted for by a poll on the club's website.[90] Prior to the start of the 2010–11 season, Arsenal renamed the coloured seating quadrants of the ground as the East Stand, West Stand, North Bank, and Clock End.[93] Akin to Highbury, this involved the installation of a clock above the newly renamed Clock End which was unveiled in a league match against Blackpool.[94]

In April 2011, Arsenal renamed two bridges near the stadium in honour of club directors Ken Friar and Danny Fiszman.[95] As part of the club's 125 anniversary celebrations in December 2011, Arsenal unveiled three statues of former captain Tony Adams, record goalscorer Thierry Henry and manager Herbert Chapman outside of the stadium.[96] In February 2014, before Arsenal's match with Sunderland, the club unveiled a statue of former striker Dennis Bergkamp, outside the west stand of Emirates Stadium.[97]

Banners and flags, often designed by supporters group REDaction, are hung around the ground. A large "49" flag, representing the run of 49 unbeaten league games, is passed around the lower tier before kick off.

Expansion and future developments

As of 2008, Arsenal's season ticket waiting list stood at 40,000 people.[98] The potential for expanding the stadium is a common topic within fan debate. Potential expansion methods include, make seats smaller, filling in the dips in the corners of the stadium though this would block airflow, and replacing the roof with a third level and building a new roof. There has also been discussion on the implementation of safe standing.[99]

Other uses

| Summer | Artist |

|---|---|

| 2008 | Bruce Springsteen |

| 2009 | Capital FM's Summertime Ball |

| 2012 | Coldplay |

| 2013 | Muse, Green Day |

As well as functioning as a football stadium, the Emirates Stadium also operates as a conference centre and music venue.[100] On 27 March 2008, the Emirates Stadium played host to a summit between British Prime Minister Gordon Brown and French President Nicolas Sarkozy, in part because the stadium was regarded as "a shining example of Anglo–French co-operation".[101] When used as a music venue, the capacity can be up to 72,000 as opposed to 60,432 the capacity for domestic football matches. Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band became the first band to play a concert at the stadium on 30 May 2008. They played a second gig the following night. British band Coldplay played three concerts at the Emirates in the June 2012, having sold out the first two dates within 30 minutes of going on sale. They were the first band to sell out the stadium for music purposes. A full list of the concerts played so far at the stadium can be seen at the side. The June 2013 Green Day concert broke the record attendance at the stadium.

International football matches

The stadium has also been used for a number of international friendly matches all of which have featured the Brazil national football team. The first match was against Argentina on 3 September 2006 which ended in a 3–0 victory for Brazil.[102]

| 3 September 2006 | Brazil |

3–0 | |

London |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16:00 BST | Elano Kaká |

Report | Stadium: Emirates Stadium[102] Attendance: 59,032 Referee: Steve Bennett (England) |

| 5 February 2007 | Brazil |

0–2 | |

London |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20:00 GMT | Report | Simão Carvalho |

Stadium: Emirates Stadium[103] Attendance: 59,793 Referee: Martin Atkinson (England) |

| 26 March 2008 | Brazil |

1–0 | |

London |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19:45 GMT | Pato |

Report | Stadium: Emirates Stadium[104] Attendance: 60,021 Referee: Mike Riley (England) |

| 9 February 2009 | Brazil |

2–0 | |

London |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 19:45 GMT | Elano Robinho |

Report | Stadium: Emirates Stadium[105] Attendance: 60,077 Referee: Howard Webb (England) |

| 2 March 2010 | Brazil |

2–0 | |

London |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20:05 GMT | Andrews Robinho |

Report | Stadium: Emirates Stadium[106] Attendance: 40,082 Referee: Mike Dean (England) |

| 27 March 2011 | Brazil |

2–0 | |

London |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14:00 GMT | Neymar |

Report | Stadium: Emirates Stadium[107] Attendance: 53,087 Referee: Howard Webb (England) |

Records

It is difficult to get accurate attendance figures as Arsenal do not release these, but choose to use tickets sold.[109] The highest attendance for an Arsenal match at Emirates Stadium as of 2012 is 60,161, for a 2–2 draw with Manchester United on 3 November 2007.[110] The average attendance for competitive first-team fixtures in the stadium's first season, 2006–07, was 59,837, with a Premier League average attendance of 60,045.[111] The Record for the most away fans that have attended the Emirates Stadium was 9,000, set by Plymouth Argyle, where Arsenal won 3–1 in the FA Cup 3rd round in 2009. The lowest attendance for an Arsenal match at Emirates Stadium as of 2012 is 46,539 against Shrewsbury Town in the Football League Cup third round on 20 September 2011, where Arsenal won 3–1.[112] The first player to score in a league game at the Emirates Stadium was Aston Villa's Olof Mellberg after 53 minutes. The first Arsenal player to score at the Emirates Stadium was midfielder Gilberto Silva.

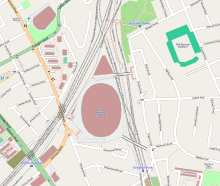

Transport and access

The Emirates Stadium is served by a number of London Underground stations and bus routes. Arsenal tube station is the closest for the northern portion of the stadium, with Highbury & Islington tube station servicing the southern end.[113] While Holloway Road tube station is the closest to the southern portion, it is entry-only before matches and exit-only afterwards to prevent overcrowding. Drayton Park station, adjacent to the Clock End Bridge is shut on matchdays as the rail services to this station do not operate at weekends nor after 10 pm.[114] £7.6 million was set aside in the planning permission for upgrading Drayton Park and Holloway Road; however Transport for London decided not to upgrade either station, in favour of improvement works at the interchanges at Highbury & Islington and Finsbury Park, both of which are served by Underground and First Capital Connect services and are approximately a ten-minute walk away. The Emirates Stadium is the only football stadium that stands beside the East Coast Main Line between London and Edinburgh and is just over 2 miles from London King's Cross.[115]

Driving to the Emirates Stadium is strongly discouraged as there are strict matchday parking restrictions in operation around the stadium.[113] An hour before kick-off to one hour after the final whistle there is a complete ban on vehicle movement on a number of the surrounding roads, except for Islington residents and businesses with a road closure access permit.[116] The parking restrictions mean that the stadium is highly dependent on the Underground service, particularly when there is no overground service in operation.[117] Industrial action on a matchday in December 2012 forced Arsenal to reschedule the match for the following month.[117]

The stadium opens to ticket holders two hours before kick-off.[118] The main club shop, named 'The Armoury', and ticket offices are located near the West Stand, with other an additional store at the base of the North Bank Bridge, named 'All Arsenal' and the 'Arsenal Store' next to Finsbury Park station.[119] Arsenal operates an electronic ticketing system where members of 'The Arsenal' (the club's fan membership scheme) use their membership cards to enter the stadium, thus removing the need for turnstile operators. Non-members are issued with one-off paper tickets embedded with an RFID tag allowing them to enter the stadium.

References

- ↑ "The real capacity of Emirates Stadium". www.arsenal.com. The Arsenal Football Club plc. Retrieved 28 July 2016.

- 1 2 Media Group, Arsenal (24 July 2008). "Stadium FAQs". www.arsenal.com. The Arsenal Football Club plc. Archived from the original on 1 July 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ↑ "Emirates Stadium". Populous. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ↑ Spurling, p. 85.

- ↑ Media Group, Arsenal (24 September 2009). "Arsenal celebrates Highbury Square opening". www.arsenal.com. The Arsenal Football Club plc. Archived from the original on 7 July 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ↑ "Statement of Accounts and Annual Report 2009/10" (PDF). www.arsenal.com. Arsenal Holdings plc. 24 September 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 7 July 2016.

- ↑ Davenport, Peter (15 May 1989). "Fans to tell inquiry of disaster on terraces". The Times. London. p. 2.

- ↑ "Hillsborough: How Taylor ensured there would never be a repeat". Yorkshire Post. Leeds. 13 April 2009. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- 1 2 Brown, p. 54.

- ↑

- ↑ Prynn, Jonathan (11 May 1991). "Bonds issue will fund Arsenal's £20m upgrading". The Times. London. p. 40.

- ↑ Brown, p. 55.

- ↑ Brown, p. 57.

- ↑ Murray, Callum (11 August 1993). "A grand stand for football". The Independent. London. Retrieved 17 February 2012.

- 1 2 Glinert, p. 105.

- ↑ Garner, Clare (18 August 1997). "Arsenal consider leaving hallowed marble halls". The Independent. London. Retrieved 4 March 2012.

- ↑ Bernstein, p. 214.

- ↑ Conn, p. 66.

- ↑ Jury, Louise (18 July 1997). "Arsenal's marble halls are saved for posterity". The Independent. London. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Conn, p. 67.

- ↑ "Gunners aim for the twin towers". BBC News. BBC. 19 January 1998. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ↑ "Arsenal offer to buy Wembley". BBC News. BBC. 12 March 1998. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ↑ "Arsenal tempted by move to Wembley". Daily Mail. London. 23 October 1998. Retrieved 18 February 2012.

- ↑ Campbell, Denis; Mathiason, Nick (12 November 2000). "Rocky road to new Wembley". The Observer. London. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- 1 2 Spurling, p. 86.

- ↑ Glinert, p. 106.

- 1 2 "Winners and losers in £400m plan". Evening Standard. London. 11 December 2001. Retrieved 19 February 2012.

- ↑ Bond, David (7 November 2000). "Residents' opposition group call for public inquiry". Evening Standard. London. p. 91.

- 1 2 Conn, p. 68.

- ↑ Wallace, Sam (4 October 2001). "Pressure group threaten public inquiry into Arsenal proposals for new stadium". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ "Mayor backs Arsenal plan". BBC. 12 October 2001. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- ↑ Smith, Alan (4 December 2001). "Highbury provides a fitting backdrop". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ Clarke, Richard (6 December 2001). "Islington battle for Arsenal". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ Lawrence, Amy (6 December 2001). "Arsenal united as United regroup". The Observer. London. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- 1 2 Hayward, Paul (11 December 2001). "Ambitious Arsenal home in on dream". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ Glinert, p. 107.

- ↑ "Arsenal given Ashburton Grove all clear". The Guardian. London. 31 July 2002. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ "Firms lose Arsenal stadium fight". BBC News. BBC. 18 January 2005. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ "Residents lose fight to keep streets open". Islington Gazette. 5 July 2006. Archived from the original on 10 December 2006. Retrieved 21 February 2012.

- ↑ Conn, p. 59.

- ↑ "Nic: I made the Gunners". The Sun. 10 September 2002. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 Teather, David (8 September 2000). "Media kick-off Granada grabs stake in the Gunners". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ Andrews, Cole, Silk, p. 181.

- ↑ Ley, John (8 September 2000). "£47m Granada deal boosts Arsenal stadium plans". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Conn, p. 69.

- ↑ Bond, David (4 April 2002). "£30m wait for Arsenal". Evening Standard. London. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ "Arsenal to cut wages after £22m loss". The Guardian. London. 3 September 2002. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ Hart, Simon (19 January 2003). "North London united". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ "Gunners new stadium delayed". The Guardian. London. 16 April 2003. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ "Cost of Gunners' stadium shoots up". The Guardian. London. 22 October 2002. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ Bose, Mihir (6 May 2003). "Arsenal ask fans to dig deep". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ Simons, Raoul (7 May 2003). "Arsenal fans give bond plan cold reception". Evening Standard. London. p. 70.

- ↑ "Arsenal sign new kit deal". BBC Sport. 8 August 2003. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ Bose, Mihir (14 August 2003). "Arsenal shirt deal falls short of new ground costs". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ "Arsenal confirms funding for Stadium project". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. 23 February 2004. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- 1 2 "Arsenal secure stadium cash". BBC Sport. 23 February 2004. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ Bose, Mihir (20 January 2005). "Arsenal £260m bond plan". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 24 February 2012.

- ↑ "Arsenal sell £260 million bond to help finance stadium". ESPN Soccernet. 13 July 2006. Retrieved 8 December 2006.

- ↑ "Statement of Accounts and Annual Report 2006/2007" (PDF). Arsenal Holdings plc. 2007. Retrieved 19 December 2007.

- ↑ Gibson, Owen (24 September 2010). "Arsenal announce record pre-tax profits of £56m". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- 1 2 "Arsenal name new ground". BBC Sport. 5 October 2004. Retrieved 8 December 2006.

- ↑ Brian Dawes (26 May 2006). "The 'E' Word". Arsenal World. Retrieved 8 December 2006.

- ↑ "UEFA likely to fine Bayern for breaching advertising laws". World Soccer News. 6 October 2005. Retrieved 8 December 2006.

- ↑ Matthew Spiro (26 September 2006). "New home, old mentality at Arsenal". UEFA. Retrieved 8 December 2006.

- ↑ "Emirates and Arsenal agree new £150m deal". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. 23 November 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- ↑ "Key Facts". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ↑ "Emirates Stadium". ARCADIS. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- ↑ "Arsenal Emirates Stadium". Buro Happold. Retrieved 3 March 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Stadium Timetable". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ↑ "Diaby grabs a Seat for Success". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. 13 March 2006. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ↑ "DD GrassMaster Selected for Arsenal's New Emirates Stadium". London. PR Newswire. 18 April 2006. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ↑ "Light Fantastic – floodlights tested". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. 28 June 2006. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ↑ "Shareholders lunch 'ramp-up' event a success". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. 19 July 2006. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ↑ "Players train at Emirates Stadium". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. 20 July 2006. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ↑ "Bergkamp Testimonial: Arsenal 2–1 Ajax – Report". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. 22 July 2006. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ↑ "Duke of Edinburgh opens Emirates Stadium". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. 1 November 2006. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ↑ Davies, Caroline (27 October 2006). "Workload forced Queen to endure pain for two weeks". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 21 January 2011.

- ↑ "Queen to officially open Emirates Stadium". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. 14 September 2006. Retrieved 25 February 2012.

- ↑ "Arsenal meet The Queen at Buckingham Palace". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. 16 February 2007. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ↑ "Deloitte Football Money League 2009 | Sport Business Group | Deloitte UK". Deloitte.com. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- ↑ James, Stuart (15 December 2004). "Fans won't be priced out of Emirates Stadium". Evening Standard. London. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Emirates Stadium". Design Build Network. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ↑ Based on a quote by chief executive Keith Edelman in Management Today, quoted in: "Reasons to be cheerful". ANR. 6 August 2004. Retrieved 8 December 2006.

- 1 2 "Emirates Stadium Facts" (PDF). Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. Retrieved October 2009. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Sony Helps Arsenal To Entertain Football Fans". Sony. Retrieved 10 March 2012.

- ↑ Jackson, Jamie (4 January 2009). "Van Persie settles nerves but Arsenal fail to convince". The Observer. London. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ↑ "Commemorative busts unveiled – Pictures". Arsenal.com. 18 October 2007. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ↑ "The Arsenal Museum". Arsenal.com. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- ↑ "Supporters Forum – 26 April 2009". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. 26 April 2009. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Club begins 'Arsenalisation' of the Emirates". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. 24 August 2009. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ↑ "Arsenalisation Special – Spirit of Highbury". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. 31 October 2009. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ↑ "Two more Stadium Illustrations are unveiled". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. 24 August 2009. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ↑ "Emirates Stadium stands to be re-named". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. 19 July 2010. Retrieved 2 November 2011.

- ↑ "Clock to be placed in south end of stadium". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ↑ "Bridges named in tribute to Friar and Fiszman". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. 19 April 2011. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ↑ "Arsenal unveil statues of three legends". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. 9 December 2011. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- ↑ "Club unveils statue of Dennis Bergkamp". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. 22 February 2014. Retrieved 24 February 2014.

- ↑ "Season Ticket Waiting List". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- ↑ Gibson, Owen (30 November 2013). "Arsenal fans call for safe standing to boost atmosphere at Emirates". theguardian.com. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ↑ "World Class Conference and Banqueting". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. 4 August 2007. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- ↑ "Brown seeks 'Entente Formidable'". BBC News. BBC. 27 March 2008. Retrieved 29 February 2012.

- 1 2 Sinnott, John (3 September 2006). "Brazil 3–0 Argentina". BBC Sport. BBC. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- ↑ "Arsenal to host Brazil v Portugal". BBC Sport. BBC. 5 January 2007. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- ↑ "International football as it happened". BBC Sport. BBC. 26 March 2008. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- ↑ "Brazil v Italy photos". BBC Sport. BBC. 10 February 2009. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ↑ "Republic of Ireland 0–2 Brazil". BBC Sport. BBC. 2 March 2010. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ↑ "Scotland 0–2 Brazil". BBC Sport. BBC. 27 March 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2012.

- ↑ "Brazil v Chile". Arsenal. Arsenal. 30 January 2015. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ↑ B, John (13 August 2014). "Arsenal's actual average attendance last season was 53,788". A is for Arsenal. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ↑ "Man Utd game attracts record attendance". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. 5 November 2007. Retrieved 24 December 2007.

- ↑ "Nearly two million through the Emirates gates". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. Retrieved 24 May 2007.

- ↑ "Arsenal 3–1 Shrewsbury". BBC Sport. BBC. 20 September 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- 1 2 "Get to... Emirates Stadium". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ "Drayton Park (DYP)". National Rail. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ Conn, David (3 May 2006). "Shadow of Arsenal's grand design hangs over the little people". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 26 March 2010.

- ↑ "Road Closures and Traffic". Islington Council. 23 December 2009. Archived from the original on 16 December 2010. Retrieved 12 May 2013.

- 1 2 "Arsenal put Wolves match back 24 hours". BBC Sport. BBC. 22 December 2011. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ↑ "Stadium: General Queries". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. Retrieved 23 February 2012.

- ↑ "The Arsenal Store Finsbury Park – SALE". Arsenal.com. Arsenal F.C. 4 February 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2011.

- Bibliography

- Andrews, David L.; Cole, Cheryl L.; Silk, Michael L. (2005). Sport and corporate nationalisms. London: Berg. ISBN 1-85973-799-4.

- Bernstein, George L (2004). The Myth of Decline: The Rise of Britain Since 1945. London: Pimlico. ISBN 1-84413-102-5.

- Brown, Adam (1998). Fanatics!: power, identity, and fandom in football. London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-18103-8.

- Conn, David (2005). The Beautiful Game?: Searching for the Soul of Football. London: Random House. ISBN 1-4464-2042-6.

- Glinert, Ed (2009). The London Football Companion: A Site-by-site Celebration of the Capital's Favourite Sport. London: Bloomsbury. ISBN 0-7475-9516-X.

- Spurling, Jon (2010). Highbury: The Story of Arsenal In, Issue 5. London: Hachette. ISBN 1-4091-0579-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Emirates Stadium. |