Environmental policy

|

| Environment |

|---|

|

|

|

Environmental policy refers to the commitment of an organization to the laws, regulations, and other policy mechanisms concerning environmental issues. These issues generally include air and water pollution, waste management, ecosystem management, maintenance of biodiversity, the protection of natural resources, wildlife and endangered species. Policies concerning energy or regulation of toxic substances including pesticides and many types of industrial waste are part of the topic of environmental policy. This policy can be deliberately taken to direct and oversee human activities and thereby prevent harmful effects on the biophysical environment and natural resources, as well as to make sure that changes in the environment do not have harmful effects on humans.[1]

Definition

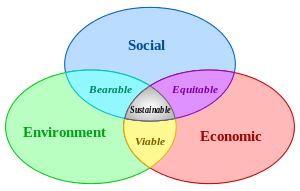

It is useful to consider that environmental policy comprises two major terms: environment and policy. Environment refers to the physical ecosystems, but can also take into consideration the social dimension (quality of life, health) and an economic dimension (resource management, biodiversity).[2] Policy can be defined as a "course of action or principle adopted or proposed by a government, party, business or individual".[3] Thus, environmental policy focuses on problems arising from human impact on the environment, which retroacts onto human society by having a (negative) impact on human values such as good health or the 'clean and green' environment.

Environmental issues generally addressed by environmental policy include (but are not limited to) air and water pollution, waste management, ecosystem management, biodiversity protection, the protection of natural resources, wildlife and endangered species, and the preservation of these natural resources for future generations. Relatively recently, environmental policy has also attended to the communication of environmental issues.[4]

Rationale

The rationale for governmental involvement in the environment is market failure in the form of forces beyond the control of one person, including the free rider problem and the tragedy of the commons. An example of an externality is when a factory produces waste pollution which may be dumped into a river, ultimately contaminating water. The cost of such action is paid by society-at-large, when they must clean the water before drinking it and is external to the costs of the factory. The free rider problem is when the private marginal cost of taking action to protect the environment is greater than the private marginal benefit, but the social marginal cost is less than the social marginal benefit. The tragedy of the commons is the problem that, because no one person owns the commons, each individual has an incentive to utilize common resources as much as possible. Without governmental involvement, the commons is overused. Examples of tragedies of the commons are overfishing and overgrazing.[5]

Instruments, problems, and issues

Environmental policy instruments are tools used by governments to implement their environmental policies. Governments may use a number of different types of instruments. For example, economic incentives and market-based instruments such as taxes and tax exemptions, tradable permits, and fees can be very effective to encourage compliance with environmental policy.[6]

Bilateral agreements between the government and private firms and commitments made by firms independent of government requirement are examples of voluntary environmental measures. Another instrument is the implementation of greener public purchasing programs.[7]

Several instruments are sometimes combined in a policy mix to address a certain environmental problem. Since environmental issues have many aspects, several policy instruments may be needed to adequately address each one. Furthermore, a combination of different policies may give firms greater flexibility in policy compliance and reduce uncertainty as to the cost of such compliance.

Government policies must be carefully formulated so that the individual measures do not undermine one another, or create a rigid and cost-ineffective framework. Overlapping policies result in unnecessary administrative costs, increasing the cost of implementation.[8] To help governments realize their policy goals, the OECD Environment Directorate collects data on the efficiency and consequences of environmental policies implemented by the national governments.[9] The website, www.economicinstruments.com, [10] provides database detailing countries' experiences with their environmental policies. The United Nations Economic Commission for Europe, through UNECE Environmental Performance Reviews, evaluates progress made by its member countries in improving their environmental policies.

The current reliance on a market-based framework is controversial, however, and many environmentalists contend that a more radical, overarching approach is needed than a set of specific initiatives, to deal with the climate change. For example, energy efficiency measures may actually increase energy consumption in the absence of a cap on fossil fuel use, as people might drive more fuel-efficient cars. Thus, Aubrey Meyer calls for a 'framework-based market' of contraction and convergence. The Cap and Share and the Sky Trust are proposals based on the idea.

Environmental impact assessments (EIA) are conducted to compare impacts of various policy alternatives. Moreover, it is assumed that policymakers make rational decisions based on the merits of the project. Eccleston and March argue that although policymakers normally have access to reasonably accurate information, political and economic factors often lead to environmentally destructive decisions in the long run.

The decision-making theory casts doubt on this premise. Irrational decisions are reached based on unconscious biases, illogical assumptions, and the desire to avoid ambiguity and uncertainty.[11]

Eccleston identifies and describes five of the most critical environmental policy issues facing humanity: water scarcity, food scarcity, climate change, the peak oil, and the population paradox.[12]

Research and innovation policy

Synergic to the environmental policy is the environmental research and innovation policy. An example is the European environmental research and innovation policy, which aims at defining and implementing a transformative agenda to greening the economy and the society as a whole so to achieve a truly sustainable development. Europe is particularly active in this field, via a set of strategies, actions and programmes to promote more and better research and innovation for building a resource-efficient, climate resilient society and thriving economy in sync with its natural environment. Research and innovation in Europe are financially supported by the programme Horizon 2020, which is also open to participation worldwide.[13]

History

The 1960s marked the beginning of modern environmental policy making. Although mainstream America remained oblivious to environmental concerns, the stage had been set for change by the publication of Rachel Carson's New York Times bestseller Silent Spring in 1962. Earth Day founder Gaylord Nelson, then a U.S. Senator from Wisconsin, after witnessing the ravages of the 1969 massive oil spill in Santa Barbara, California. Administrator Ruckelshaus was confirmed by the Senate on December 2, 1970, which is the traditional date used as the birth of the agency. Five months earlier, in July 1970, President Nixon had signed Reorganization Plan No. 3 calling for the establishment of EPA in July 1970. At the time, Environmental Policy was a bipartisan issue and the efforts of the United States of America helped spark countries around the world to create environmental policies.[14] During this period, legislation was passed to regulate pollutants that go into the air, water tables, and solid waste disposal. President Nixon signed the Clean Air Act in 1970 which set the USA as one of the world leaders in environmental conservation.

In the European Union, the very first Environmental Action Programmed was adopted by national government representatives in July 1973 during the first meeting of the Council of Environmental Ministers.[15] Since then an increasingly dense network of legislation has developed, which now extends to all areas of environmental protection including air pollution control, water protection and waste policy but also nature conservation and the control of chemicals, biotechnology and other industrial risks. EU environmental policy has thus become a core area of European politics.

Overall organizations are becoming more aware of their environmental risks and performance requirements. In line with the ISO 14001 standard they are developing environmental policies suitable for their organization. This statement outlines environmental performance of the organization as well as its environmental objectives. Written by top management of the organization they document a commitment to continuous improvement and complying with legal and other requirements, such as the environmental policy objectives set by their governments.

Environmental policy integration

The concept of environmental policy integration (EPI) refers to the process of integrating environmental objectives into non-environmental policy areas, such as energy, agriculture and transport, rather than leaving them to be pursued solely through purely environmental policy practices. This is oftentimes particularly challenging because of the need to reconcile global objectives and international rules with domestic needs and laws.[16] EPI is widely recognised as one of the key elements of sustainable development. More recently, the notion of ‘climate policy integration’, also denoted as ‘mainstreaming’, has been applied to indicate the integration of climate considerations (both mitigation and adaptation) into the normal (often economically focused) activity of government.[17]

Environmental policy studies

Given the growing need for trained environmental practitioners, graduate schools throughout the world offer specialized professional degrees in environmental policy studies. While there is not a standard curriculum, students typically take classes in policy analysis, environmental science, environmental law and politics, ecology, energy, and natural resource management. Graduates of these programs are employed by governments, international organizations, private sector, think tanks, universities, and so on.

Due to the lack of standard nomenclature, institutions use varying designations to refer to academic degrees they award. However, the degrees typically fall in one of four broad categories: master of arts, master of science, master of public administration, and PhD in environmental policy. Sometimes, more specific names are used to reflect the focus of the academic program. For example, the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey awards master of arts in international environmental policy (MAIEP) to emphasize the international orientation of the curriculum.[18]

See also

- Chemical leasing

- Climate policy

- Environmental governance

- Environmental politics

- Environmental Principles and Policies (book)

- Harris School of Public Policy Studies

- List of environmental degree-granting institutions

- Tellus Institute

- Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey

References

- ↑ McCormick, John (2001). Environmental Policy in the European Union. The European Series. Palgrave. p. 21.

- ↑ Bührs, Ton; Bartlett, Robert V (1991). Environmental Policy in New Zealand. The Politics of Clean and Green. Oxford University Press. p. 9.

- ↑ Concise Oxford Dictionary, 1995.

- ↑ A major article outlining and analyzing the history of environmental communication policy within the European Union has recently come out in The Information Society, a journal based in the United States. See Mathur, Piyush. "Environmental Communication in the Information Society: The Blueprint from Europe," The Information Society: An International Journal, 25: 2, March 2009 , pp. 119–38. Accessible: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/content~content=a909229825~db=all~jumptype=rss

- ↑ Rushefsky, Mark E. (2002). Public Policy in the United States at the Dawn of the Twenty-first Century (3rd ed.). New York: M.E. Sharpe, Inc. pp. 253–254. ISBN 978-0-7656-1663-0.

- ↑ http://www.oecd.org/about/0,3347,en_2649_34281_1_1_1_1_1,00.html http://www.oecd.org/about/0,3347,en_2649_34295_1_1_1_1_1,00.html

- ↑ en_2649_34281_1_1_1_1_ 1,00.html Archived June 10, 2015, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Instrument Mixes for Environmental Policy" (Paris: OECD Publications, 2007) 15–16.

- ↑ “Environmental Policies and Instruments,” http://www.oecd.org/department/0,3355,en_2649_34281_1_1_1_1_1,00.html

- ↑ "Economic Instruments". Economic Instruments. 2011-01-26. Retrieved 2012-11-02.

- ↑ Eccleston C. and Doub P., Preparing NEPA Environmental Assessments: A Users Guide to Best Professional Practices, CRC Press Inc., 300 pages (publication date: March 2012).

- ↑ Eccleston C. and March F., Global Environmental Policy: Principles, Concepts And Practice, CRC Press Inc. 412 pages (2010).

- ↑ See Horizon 2020 – the EU's new research and innovation programme http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-13-1085_en.htm

- ↑ “Managing the Environment, Managing Ourselves: A History of American Environmental Policy”

- ↑ Knill, C. and Liefferink, D. (2012) The establishment of EU environmental policy. In: Jordan, A.J. and C. Adelle (ed.) Environmental Policy in the European Union: Contexts, Actors and Policy Dynamics (3e). Earthscan: London and Sterling, VA.

- ↑ Farah, Paolo Davide; Rossi, Piercarlo (December 2, 2011). "National Energy Policies and Energy Security in the Context of Climate Change and Global Environmental Risks: A Theoretical Framework for Reconciling Domestic and International Law Through a Multiscalar and Multilevel Approach". European Energy and Environmental Law Review. 2 (6): 232–244. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ↑ Taskforce on Conceptual Foundations of Earth System Governance http://www.earthsystemgovernance.net/conceptual-foundations/?page_id=144

- ↑ Monterey Institute of International Studies. "MA in International Environmental Policy". Miis.edu. Retrieved 2012-11-02.

External links

- GreenWill Global nonprofit initiative offering free environmental policies ("Green Policy") worldwide

- Envirowise UK Portal Government funded site offering environmental policy advice

- Responding to Climate Change Climate Change organization publishing annually since 2002.

- Resources for the Future A nonprofit and nonpartisan organization that conducts independent research—rooted primarily in economics and other social sciences—on environmental, energy, and natural resource issues.

- EEA/OECD Environmental Policy and Natural Resource Management database

- US National Environmental Policy Act

- Schelling, Thomas C. (2002). "Greenhouse Effect". In David R. Henderson (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (1st ed.). Library of Economics and Liberty. OCLC 317650570, 50016270, 163149563

- In December 1997 Pakistan Environmental Protection Act (PEPA'97) was signed and promulgated by the President of Pakistan. It provides for the protection, conservation, rehabilitation and improvement of the environment, for the prevention and control of pollution, and promotion of sustainable development. PEPA'97 covers nearly all issues from pollution generation to pollution prevention, monitoring to confiscation, compliance to violation, and prosecution to penalization. However, results of this legislation are subjected to virtuous and unadulterated implementation.

- Burden, L. 2010, How to write an environmental policy (for organizations), <http://www.environmentalpolicy.com.au/>