Equitable interest

| Equitable doctrines |

|---|

|

| Doctrines |

| Defences |

| Equitable remedies |

| Related |

An equitable interest is an "interest held by virtue of an equitable title (a title that indicates a beneficial interest in property and that gives the holder the right to acquire formal legal title) or claimed on equitable grounds, such as the interest held by a trust beneficiary."[1] The equitable interest is a right in equity that may be protected by an equitable remedy. This concept exists only in systems influenced by the common law (connotation 2) tradition, such as New Zealand, England, Canada, Australia and the United States.

Equity

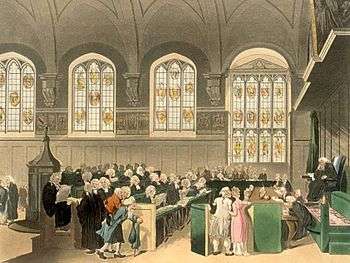

Equity is a concept of rights distinct from legal (that is, common law) rights; it is (or, at least, it originated as) "the body of principles constituting what is fair and right (natural law)".[2] It was "the system of law or body of principles originating in the English Court of Chancery and superseding the common and statute law (together called 'law' in the narrower sense) when the two conflict".[2] In equity, a judge determines what is fair and just and makes a decision as opposed to deciding what is legal.

Perhaps the most common example of an equitable interest is the interest of a beneficiary under a trust. Under a trust, the trustee has a legal interest in the trust property and all of the rights and powers that follow from that legal interest (for example, rights to deal with that trust property and to invest trust property), subject to the interest of the beneficiary and the terms of the trust (deed). The beneficiaries under the trust has an equitable interest in the trust property. The precise nature of the interests and rights of the beneficiary under a trust is contested. More than merely being a theoretical matter, however, the nature of those rights -- whether they are rights in personam, rights in rem, a combination of the two, or something else entirely -- has important implications, particularly in the fields of insolvency law and private international law.

The rights and obligations of the beneficiary, trustee, third parties contracting with the trust and potentially of other parties (such as the settlor of the trust or, if the trust provides for such, a protector or enforcer of the trust) depend on the terms of the trust deed. Trust law includes both mandatory law (that is, law which cannot be excluded, such as the irreducible core, information rights and the supervisory jurisdiction of the court) and default law (that is, law which can be excluded by express provision in the trust deed). The trust deed, therefore, has a significant role to play in determining the rights and obligations of the parties in that default law (such as fiduciary obligations and rights of recourse against non-entitled third parties) may be excluded or modified by the trust deed.

If a person has an equitable interest in property, this implies that some other person has the legal interest in that property. If one person has both the legal and equitable interest in the relevant property, he or she has no ‘equitable interest’ in that property as such.[3] “If one person has both the legal estate and the entire beneficial interest in the land he holds an entire and unqualified legal interest and not two separate interests, one legal and the other equitable”.[4][5] As stated by Brennan J in DKLR Holding Co (No 2) Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Stamp Duties (NSW),[6] "[an] equitable interest is not carved out of a legal estate but impressed upon it".[7]

Land law

An enforceable contract for sale confers an equitable interest on the purchaser of the land, as per the rule established in Lysaght v Edwards[8] It was similarly held in Walsh v Lonsdale that 'equity looks on as done that which ought to be done'.[9] A contract, which does not meet the requirements of a deed, required by the Law of Property Act 1925 s.52(1), may be specifically enforced to convey the equitable interest to the new purchaser. This rule has had a significant impact because it allows interests that have not been conveyed by a deed to still be binding on future purchasers, through the doctrine of constructive notice. However, the UK Parliament has weakened the impact of this rule, with the Law of Property (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1989 s.2,[10] which requires all contracts for the sale of land (which could be specifically enforceable) to be in writing, to contain all the terms of the agreement and be signed by both parties. Any contracts that are not in writing and signed by both parties cannot be specifically enforced and so will not create or transfer an equitable interest in land.

See also

References

- ↑ Black's Law Dictionary. Second Pocket Edition. p. 361. 2001 West Group. Bryan A. Garner (editor in chief)

- 1 2 Black's Law Dictionary. Second Pocket Edition. p. 241. 2001 West Group. Bryan A. Garner (editor in chief)

- ↑ “DKLR Holding Co (No 2) Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Stamp Duties (NSW)”(1982) HCA 14, 463 [7].

- ↑ DKLR Holding Co (No 2) Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Stamp Duties (NSW) (1982) HCA 14, 463 [7] (Aickin J).

- ↑ Commissioner of State Revenue v Lend Lease Funds Management Pty Ltd [2011] VSCA 182 (21 June 2011) - AustLii

- ↑ [1982] HCA 14.

- ↑ DKLR Holding Co (No 2) Pty Ltd v Commissioner of Stamp Duties (NSW) [1982] HCA 14, 474 [8] (Brennan J).

- ↑ (1876) 2 Ch.D. 499.

- ↑ (1882) 21 Ch.D. 9.

- ↑ Law of Property (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1989 s.2