Ex parte Merryman

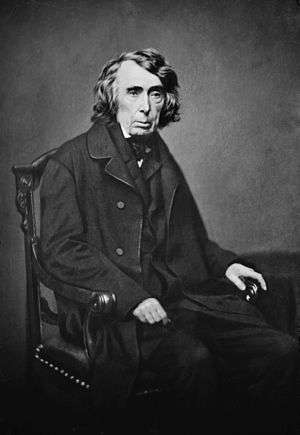

Ex parte Merryman, 17 F. Cas. 144 (C.C.D. Md. 1861) (No. 9487), is a well-known and controversial U.S. federal court case which arose out of the American Civil War.[1] It was a test of the authority of the President to suspend "the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus" under the Constitution's Suspension Clause, when Congress was in recess and therefore unavailable to do so itself.[2] U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger Taney ruled that the authority to suspend habeas corpus lay exclusively with Congress. The Executive Branch, including the Army, failed to comply with Taney's Merryman opinion, and John Merryman remained inaccessible to the judiciary (and the civilian legal authorities generally) while Congress remained in recess. Taney filed his Merryman decision with the United States Circuit Court for the District of Maryland, but it is unclear if Taney's decision was a circuit court decision. One view, based in part on Taney's handwritten copy of his decision in Merryman, is that Taney heard the habeas action under special authority granted to federal judges by Section 14 of the Judiciary Act of 1789. According to this view, Merryman was an in-chambers decision. Due to its vague jurisdictional locus and hastened disposition, the nature of the Merryman decision remains contested to this day.[3][4]

Background

When a person is detained by police or other authority, a court can issue a writ of habeas corpus, compelling the detaining authority either to show proper cause for detaining the person (e.g., by filing criminal charges) or to release the detainee. The court can then remand the prisoner to custody, release him on bail, or release him outright. Article I, Section 9 of the United States Constitution, which mostly consists of limitations upon the power of Congress, says:

The privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.

In April 1861, actual fighting in the Civil War began. President Lincoln called for the states to provide militia troops to the Federal government to suppress the rebellion. Troops traveling to Washington passed through Baltimore, Maryland. Baltimore mobs objecting to a war with the seceding states attacked some of the troop transports on April 19. It seemed possible that Maryland would attempt to block the passage of troops, cutting off Washington, and impeding a war against the South. On April 29, the Maryland Legislature voted 53–13 against secession,[5][6] but they also voted not to reopen rail links with the North, and they requested that Lincoln remove the growing numbers of federal troops in Maryland.[7] At this time the legislature seems to have wanted to avoid involvement in a war with its southern neighbors.[7] Fearful that the passage of more Union troops would provoke more rioting, and possibly an attempt to enact secession by extralegal means, Mayor George Brown of Baltimore and Governor Thomas Hicks of Maryland asked that no more troops cross Maryland, but Lincoln refused.[8] However, for the next few weeks, troops were brought to Washington via Annapolis, avoiding Baltimore. Also on April 19, Lincoln asked Attorney General Edward Bates for an opinion on the suspension of the writ of habeas corpus.

The threat to Washington was serious, and Lincoln eventually responded by delegating limited authority to the Army to suspend habeas corpus in Maryland. On April 27, 1861, he told General Winfield Scott (commanding general of the Army) that if there was any resistance on the "military line" from Annapolis to Washington, Scott or "the officer in command at the point" was authorized to suspend habeas corpus if necessary.[9]

The case

Following the Maryland legislature's April 29 directive that Maryland not be used as a passage for troops attacking the South, Governor Hicks allegedly ordered the state militia to demolish several state railroad bridges (Bush River bridge and Gunpowder River bridge). Militia Lieutenant John Merryman was arrested on May 25 by order of Brigadier General William High Keim of the United States Volunteers, for his role in destroying these bridges. Merryman was charged with treason and being a commissioned lieutenant in an organization intending armed hostility toward the government.[10][11][12]

The writs

In another Maryland habeas corpus case, just prior to Merryman, Judge William Fell Giles of the United States District Court for the District of Maryland issued a writ of habeas corpus. The commander of Fort McHenry, Major William W. Morris, wrote in reply,

At the date of issuing your writ, and for two weeks previous, the city in which you live, and where your court has been held, was entirely under the control of revolutionary authorities. Within that period United States soldiers, while committing no offense, had been perfidiously attacked and inhumanly murdered in your streets; no punishment had been awarded, and I believe, no arrests had been made for these atrocious crimes; supplies of provisions intended for this garrison had been stopped; the intention to capture this fort had been boldly proclaimed; your most public thoroughfares were daily patrolled by large numbers of troops, armed and clothed, at least in part, with articles stolen from the United States; and the Federal flag, while waving over the Federal offices, was cut down by some person wearing the uniform of a Maryland officer. To add to the foregoing, an assemblage elected in defiance of law, but claiming to be the legislative body of your State, and so recognized by the Executive of Maryland, was debating the Federal compact. If all this be not rebellion, I know not what to call it. I certainly regard it as sufficient legal cause for suspending the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus.

Morris also wrote, "If, in an experience of thirty-three years, you have never before known the writ to be disobeyed, it is only because such a contingency in political affairs as the present has never before arisen."[13]

Thus rather than approaching Judge Giles whose prior order in a Maryland habeas matter had been ignored, Merryman's lawyers went to Washington, D.C., and asked Chief Justice Taney to issue a writ of habeas corpus. Taney promptly issued the writ on Merryman's behalf on May 26, 1861; Taney ordered General George Cadwalader, the commander of the military district including Fort McHenry, where Merryman was being held, to bring Merryman before Taney the next day. Taney's order only directed Cadwalader to produce Merryman, not to release him. During that era, Supreme Court Justices sat as circuit court judges, as well. It is unclear if Taney was acting in his role as a circuit judge for the United States Circuit Court for the District of Maryland, or making use of special authority to hear habeas matters permitted to all federal judges, including the Chief Justice, under Section 14 of the Judiciary Act of 1789. Taney's reason for holding court in Maryland, rather than Washington, D.C., he states, was that it would permit Gen. Cadwalader to answer the writ in Baltimore rather than Washington, D.C., and so not have to leave the limits of his military command.[14]

Cadwalader, although himself a lawyer, had less than one day to draft a response and defense for his conduct and that of the Army. Cadwalader responded to Taney's order on May 27 by sending a colonel to explain that the Army had suspended the writ of habeas corpus under presidential authority. Cadwalader also provided a letter explaining the circumstances of Merryman's arrest, including that Merryman was arrested by Keim's subordinates for treason, and for being illegally in possession of U.S. arms, and for advocating "armed hostility against the Government." The letter declared that the public safety was still threatened and that any errors "should be on the side of safety to the country." Because of the seriousness of the charges and the complexity of the issues, Cadwalader requested an extension to reply in order that he could get further instructions from the President. Taney refused the request,[15] and instead held Cadwalader in contempt of court for refusing to produce John Merryman.[16][17] Accordingly, Taney issued a writ of attachment for Cadwalader, ordering a U.S. Marshal to seize Cadwalader and bring him before the court the following day.

Cadwalader had been sent instructions on May 28, 1861 from Army headquarters explicitly acknowledging issuance by Chief Justice Taney of the writ of habeas corpus, and ordering Cadwalader, under the President's authority, to keep holding Merryman in custody.[18][19] On that same day, the Executive Branch—i.e., a U.S. Marshal—attempted to execute Taney's writ of attachment, but the U.S. Marshal was refused entry into the fort.[14] However, there is no concrete evidence that Cadwalader was in receipt of those instructions prior to the time the Marshal was refused entrance at Fort McHenry; indeed, there is no evidence that Cadwalader ever received those instructions from Army Headquarters. Because the Marshal was unable to serve the attachment, the citation for contempt was never actually adjudicated, and at the end of the Merryman litigation, it became a nullity, as do all civil contempt orders at the termination of litigation.

Chief Justice Taney's opinion and order

On May 28, Taney stated from the bench that the President can neither suspend habeas corpus nor authorize a military officer to do it, and that military officers cannot arrest a person not subject to the rules and articles of war, except as ordered by the courts. Taney noted that, while the marshal had the right to call up the posse comitatus to assist him in seizing General Cadwalader and in bringing him before the court, it was probably unwise for the marshal to do so, as the civilian and military authorities might collide and violence ensue, and thus Taney would not punish the marshal for failing in his task. He then promised a more lengthy, written ruling within the week and ordered that it be sent to President Lincoln, "in order that he might perform his constitutional duty, to enforce the laws, by securing obedience to the process of the United States."[9] Some believe that Taney was politically a partisan Democrat and an opponent of Lincoln and that his politics infected his decision in Merryman; others believe, that a partisan Democrat or not, Taney's Merryman opinion was a simple application of well established law. The truth of the matter has never been resolved, and the Supreme Court of the United States has never squarely determined if the President has any independent authority to suspend habeas corpus.

Taney filed his written opinion on June 1, 1861 with the United States Circuit Court for the District of Maryland. In it, he argued at length against Lincoln for granting himself easily abused powers. Taney asserted that the President was not authorized to suspend habeas corpus, observing that only Parliament, not the King, had such powers under English law. Referring to other provisions in the Bill of Rights, Taney wrote:

These great and fundamental laws, which Congress itself could not suspend, have been disregarded and suspended, like the writ of habeas corpus, by a military order, supported by force of arms. Such is the case now before me, and I can only say that if the authority which the Constitution has confided to the judiciary department and judicial officers, may thus, upon any pretext or under any circumstances, be usurped by the military power, at its discretion, the people of the United States are no longer living under a government of laws, but every citizen holds life, liberty and property at the will and pleasure of the army officer in whose military district he may happen to be found.[20]

Taney noted in a footnote to the above passage that the United States Declaration of Independence listed making the military power independent of and superior to the civil power as one justification for dissolving political allegiance.[21] The Declaration of Independence states, "He has affected to render the Military independent of and superior to the Civil power." [22] Taney's opinion quoted an earlier opinion by Chief Justice John Marshall in the case of Ex Parte Bollman:[23]

If at any time the public safety should require the suspension of the powers vested by this act in the courts of the United States, it is for the Legislature to say so. That question depends on political considerations, on which the Legislature is to decide. Until the legislative will be expressed, this court can only see its duty, and must obey the laws.

According to an 1862 essay by Horace Binney, "there was nothing before Chief Justice [Marshall] to raise the distinction between Congress and the President" and in any event those lines by Chief Justice Marshall were "altogether" obiter dicta.[24]

Finally, Taney's final order in Merryman never actually ordered Cadwalader (the actual defendant), the Army, Lincoln or his administration, or anyone else to release John Merryman.

Aftermath

Lincoln explains noncompliance with Taney's opinion

Lincoln's administration did not comply with the rule of law or legal principle announced by Chief Justice Taney in his Merryman opinion, and Lincoln did not order his subordinates to comply with Taney's opinion. Alternatively, because Taney's order did not direct Lincoln to comply in any specific manner, it could be maintained that the Lincoln administration did not fail to comply with its legal obligations in connection with Merryman.

Merryman remained in custody while Congress remained in recess. Lincoln also received an opinion supporting his suspension from his Attorney General, Edward Bates.[25] The Bates opinion (or a preliminary draft of that opinion) may have influenced Lincoln's subsequent message to Congress which discussed his administration's policy in regard to habeas corpus. However, Lincoln's message to Congress was dated July 4, 1861; the Bates opinion was dated the next day, July 5, 1861. Lincoln, in his message to Congress, framed the issue as:

The whole of the laws which were required to be faithfully executed were being resisted and failing of execution in nearly one-third of the States. Must they be allowed to finally fail of execution, even had it been perfectly clear that by the use of the means necessary to their execution some single law, made in such extreme tenderness of the citizen's liberty that practically it relieves more of the guilty than of the innocent, should to a very limited extent be violated? To state the question more directly, Are all the laws but one to go unexecuted, and the Government itself go to pieces lest that one be violated? Even in such a case, would not the official oath be broken if the Government should be overthrown when it was believed that disregarding the single law would tend to preserve it? But it was not believed that this question was presented. It was not believed that any law was violated. The provision of the Constitution that "the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended unless when, in cases of rebellion or invasion, the public safety may require it" is equivalent to a provision--is a provision-that such privilege may be suspended when, in cases of rebellion or invasion, the public safety does require it. It was decided that we have a case of rebellion and that the public safety does require the qualified suspension of the privilege of the writ which was authorized to be made. Now it is insisted that Congress, and not the Executive, is vested with this power; but the Constitution itself is silent as to which or who is to exercise the power; and as the provision was plainly made for a dangerous emergency, it can not be believed the framers of the instrument intended that in every case the danger should run its course until Congress could be called together, the very assembling of which might be prevented, as was intended in this case, by the rebellion.[26]

According to historian Michael Burlingame, "Lincoln had a good argument, for Congress in that era was often out of session, and an invasion or rebellion might well take place during one of its long recesses, just as had occurred in April."[27][28] Such discussion assumes that Congress can only authorize suspension once the crisis has come, and therefore recess precludes Congress from acting. This view grossly oversimplifies the matter. Congress can act in advance of any particular crisis by laying out statutory guidelines within which presidential suspension is authorized. Thus a congressional recess, as a matter of principle, does not preclude Congress from choosing policy in regard to suspension in an emergency, such as an insurrection or invasion.

Indictment of Merryman

On July 10, by which time Congress was able to reconvene for a special session, Merryman was indicted for treason by a grand jury in Baltimore for the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland. The indictment alleged that in cooperation with 500 armed men Merryman had "most wickedly, maliciously and traitorously" waged war on the United States. He was charged with destroying six railroad bridges and the telegraph lines along the tracks, all with the intent to impede the passage of troops and obstruct vital military communications. Thirteen witness to the actions were listed. Seven other men were indicted along with Merryman. On July 13, he was released pending trial upon the posting $20,000 bail.[29]

The case never came to trial. Since treason was a capital offense, it had to be tried in the circuit court. For Maryland-related alleged crimes, this meant that Taney and District Judge William F. Giles would both hear the case, as they were the only two federal judges for the United States Circuit Court for the District of Maryland. Taney consistently refused to schedule hearings for any of those charged, claiming that he believed they would not receive a fair trial in Maryland during war time conditions. He also discouraged Judge Giles from hearing the case by himself and resisted efforts to have another Justice replace him (part of his delay was blamed on poor health). As the refusal continued into 1864, Taney wrote to Justice Samuel Nelson that, "I will not place the judicial power in this humiliating position nor consent to degrade and disgrace it, and if the district attorney presses the prosecutions I shall refuse to take them up."[30] It must also be noted that Salmon P. Chase, who succeeded Taney as Chief Justice and as circuit judge for Maryland, delayed hearing Merryman and other similar Maryland treason cases. Chase was appointed by President Lincoln; he was no partisan Democrat.

Congressional response

After reconvening in July, Congress failed to pass a bill favored by Lincoln to explicitly approve his habeas corpus suspensions and to authorize the administration to continue them.[31] The administration would continue the arrests, regardless, with a new wave of arrests beginning in Maryland in September 1861. However, Congress did adopt more general retroactive language rendering Lincoln's previous actions during the spring "in all respects legalized".[32]

In March 1862 U.S. Congressman Henry May (D-Maryland), who had been imprisoned in the new wave of arrests and held without charges from September 1861 - December 1861, introduced a bill requiring the Federal government either to indict by grand jury or release all other "political prisoners" still held without habeas corpus.[33] May's bill passed the House in summer 1862, and its position would later be included in the 1863 Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, which would require actual indictments for suspected traitors.[34]

The passage of the 1863 Habeas Corpus Suspension Act in March 1863 finally ended the controversy, at least temporarily, by authorizing presidential suspension of the writ during the Civil War, but requiring indictment by grand jury (or release) of political prisoners, and by indemnifying federal officials who had arrested citizens without habeas in the previous two years. It has been argued that after this Act was passed, Lincoln and his administration continued to arrest and hold prisoners without giving such prisoners the procedural protections mandated by the Act. In doing so, Lincoln and his administration relied wholly on presidential power claims.

Later discussion by courts

The rest of the U.S. Supreme Court had nothing to do with Merryman, and the other two justices from the South, John Catron and James Moore Wayne, acted as Unionists. For instance, Catron's charge to a Saint Louis grand jury, saying that armed resistance to the federal government was treason, was quoted in the New York Tribune of July 14, 1861.[35] On circuit, Catron closely cooperated with military authorities.[36]

Several district and circuit court rulings followed Taney's opinion.[37] However, according to historian Harold Hyman, most northern lawyers accepted Lincoln's view that Taney's opinion in Merryman was "ultimately reversible by political processes", and Taney's opinion in that case "convinced no other justices and few lower federal judges."[38] However, Taney's Merryman opinion was adopted by some lower courts, such as the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York and the Supreme Court of Wisconsin. See, e.g., Ex parte McQuillon, 16 F. Cas. 347, 348 (S.D.N.Y. 1861) (No. 8294) (Betts, J.) (“[Judge Betts] would, however, follow out that case [Merryman], but would express no opinion whatever, as it would be indecorous on his part to oppose the [C]hief [J]ustice. He would therefore decline taking any action on the writ at all.”); In re Kemp, 16 Wis. 359, 1863 WL 1066, at *8 (1863) (Dixon, C.J.) (“I deem it advisable, adhering to the precedent set by other courts and judges under like circumstances, and out of respect to the national authorities, to withhold [granting habeas relief] until they shall have had time to consider what steps they should properly take in the case.”). Just as Taney chose not to grant John Merryman relief at the termination of litigation, Betts and Dixon also refused to grant the litigants before them, who were situated similar to Merryman, release from imprisonment.

The Merryman decision is still among the best-known Civil War-era court cases and one of Taney's most famous opinions, alongside the Dred Scott case. Its legal argument holding that Congress alone may suspend the writ was restated by Justice Antonin Scalia in a dissenting opinion in the case of Hamdi v. Rumsfeld.[32][39] The Hamdi case, though, did not involve any suspension of the writ, much less a suspension by the President while Congress was unavailable, and no U.S. Supreme Court decision has ever squarely endorsed or rejected Taney's opinion in Merryman.[32]

Historical Context

Controversy

In the month preceding the Merryman case, Baltimore Mayor Brown,[40] the entire city council, the police commissioner, and the entire Board of Police, were arrested and imprisoned at Fort McHenry without charges, creating some controversy.[41][42] In September after the Merryman ruling, and in disregard of it, the Army arrested sitting U.S. Congressman Henry May (D-Maryland), and fully one third of the members of the Maryland General Assembly, and expanded the geographical zone within which the writ of habeas corpus was suspended.[41] When prominent Baltimore newspaper editor Frank Key Howard (Francis Scott Key's grandson) in a September editorial criticized Lincoln's failure to comply with Chief Justice Taney's Merryman opinion, Howard was himself arrested by Federal troops under orders from Lincoln's Secretary of State Seward and held without charge or trial. Howard described these events in his 1863 book Fourteen Months in American Bastiles, where he noted that he was imprisoned in Fort McHenry, the same fort where the Star Spangled Banner had been waving "o'er the land of the free" in his grandfather's song.[43] Two of the publishers selling his book were then arrested.[41] In all nine newspapers were shut-down in Maryland by the federal government, and a dozen newspaper owners and editors like Howard were imprisoned without charges.[41]

In October 1861 one John Murphy asked the United States Circuit Court for the District of Columbia to issue a writ of habeas corpus for his son, then in the United States Army, on the grounds that he was underage. When the writ was delivered to General Andrew Porter Provost Marshal of the District of Columbia he had both the lawyer delivering the writ and the United States Circuit Judge William Matthew Merrick, who issued the writ, arrested to prevent them from proceeding in the case United States ex rel. Murphy v. Porter. Merrick's fellow judges took up the case and ordered General Porter to appear before them, but Lincoln's Secretary of State Seward prevented the federal marshal from delivering the court order.[44] The court objected that this disruption of its process was unconstitutional as the president had not declared martial law (while acknowledging that he did have the power to do so), but noted that it was powerless to enforce its prerogatives.[45][46]

In November 1861 Judge Richard Bennett Carmichael, a presiding state circuit court judge in Maryland, was imprisoned without charge for releasing, due to his concern that arrests were arbitrary and civil liberties had been violated, many of the southern sympathizers seized in his jurisdiction. The order came from Secretary of State Seward. The federal troops executing Judge Carmichael's arrest beat him unconscious in his courthouse while his court was in session before dragging him out, initiating yet another public controversy.[47]

Aftermath

In early 1862, Lincoln took a step back from the suspension of habeas corpus controversy. On February 14, he ordered most political prisoners released, with some exceptions (such as editor Howard), and offered them amnesty for past treason or disloyalty, so long as they did not aid the Confederacy.[48] In March 1862, U.S. Congressman May, who had been released in December 1861, introduced a bill requiring the Federal government either to indict by grand jury or release all other "political prisoners" still held without habeas corpus.[49] May's bill passed the House in summer 1862, and its position would later be included in the 1863 Habeas Corpus Suspension Act, which would require actual indictments for suspected traitors.[50]

Seven months later, faced with opposition to his calling up of the militia, Lincoln again suspended habeas corpus, this time through the entire country, and made anyone charged with interfering with the draft, discouraging enlistments, or aiding the Confederacy subject to martial law.[51] In the interim, the controversy continued with several calls made for prosecution of those who acted under Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus. Former Secretary of War Simon Cameron had even been arrested in connection with a suit for trespass vi et armis, assault and battery, and false imprisonment.[52]

Although in spring 1861 Maryland Governor Hicks had requested that Lincoln not transport troops through the state and, upon the president's refusal, had allegedly ordered the destruction of Maryland bridges so as to prevent further federal troop transports – the execution of which order had led to Merryman's original arrest – later in the war Hicks, now a U.S. Senator, would claim, "I believe that arrests and arrests alone saved the State of Maryland not only from greater degradation than she suffered, but from everlasting destruction...I approved them [the arrests] then, and I approve them now; and the only thing for which I condemn the Administration in regard to that matter is that they let some of these men out."[53]

See also

- United States ex rel. Murphy v. Porter (1861)

- Ex parte Milligan (1866)

- Habeas corpus in the United States

- Taney Arrest Warrant

- Maryland in the Civil War

Notes

- ↑ McGinty (2011) p. 173. "The decision was controversial on the day it was announced, and it has remained controversial ever since." Neely (2011) p. 65 Quoting Lincoln biographer James G. Randall, "Perhaps no other feature of Union policy was more widely criticized nor more stenuously defended."

- ↑ William H. Rehnquist, All the Laws But One (New York: Knopf, 1998), 27–39.

- ↑ See Bruce A. Ragsdale, Ex parte Merryman and Debates on Civil Liberties During the Civil War, pages 11 & 15 (Federal Judicial History Office 2007), http://www.fjc.gov/history/docs/merryman.pdf

- ↑ Seth Barrett Tillman, Ex parte Merryman: Myth, History, and Scholarship, 224 Military Law Review 481 (2016) (peer reviewed), url=http://ssrn.com/abstract=2646888

- ↑ Mitchell, p.87

- ↑ "States Which Seceded". eHistory. Civil War Articles. Ohio State University. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved October 16, 2014.

- 1 2 "Teaching American History in Maryland – Documents for the Classroom: Arrest of the Maryland Legislature, 1861". Maryland State Archives. 2005. Archived from the original on January 11, 2008. Retrieved February 6, 2008.

- ↑ "He reminded them that Union soldiers were neither birds who could fly over Maryland nor moles who could burrow underground... 'Go home and tell your people that if they do not attack us, we will not attack them; but if they do attack us, we will return it, and that severely.'" Simon, James F. (2007). Lincoln and Chief Justice Taney: Slavery, Secession, and the President's War Powers. New York: Simon & Schuster. p. 185. ISBN 0-7432-5033-8.

- 1 2 Ex parte Merryman, 17 F. Cas. 144, 148 (C.C.D. Md. 1861).

- ↑ Ex parte Merryman, 17 F. Cas. 144, 146 (C.C.D. Md. 1861).

- ↑ Tucker, Spencer C. American Civil War: The Definitive Encyclopedia, 2013. p. 1269

- ↑ Paludan, Phillip S. (1994). The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. p. 75. ISBN 0-7006-0671-8.

- ↑ Benson John Lossing (1866/1997), Pictorial Field Book of the Civil War, reprint, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, Vol. I, Chap. XVIII, "The Capital Secured—Maryland Secessionists Subdued—Contributions by the People", pp. 449-450, [italics in reprint].

- 1 2 Ex parte Merryman, 17 F. Cas. 144, 147 (C.C.D. Md. 1861).

- ↑ McGinty (2011) pp. 85-86

- ↑ Dirck, Brian. Lincoln and the Constitution, p. 79 (SIU Press, 2012).

- ↑ McGinty, Brian. The Body of John Merryman, p. 13 (Harvard University Press 2011).

- ↑ The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, p. 576 (U.S. Government Printing Office 1894).

- ↑ Silver, David. Lincoln's Supreme Court, p. 29 (University of Illinois Press, 1956).

- ↑ Ex parte Merryman, 17 F. Cas. 144, 152 (C.C.D. Md. 1861).

- ↑ Ex parte Merryman, 17 F. Cas. 144, 152n3 (C.C.D. Md. 1861).

- ↑ Jefferson, Thomas. "IN CONGRESS, July 4, 1776. The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America,". National Archives. The National Archives and Records Administration. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- ↑ Ex Parte Bollman, 8 U.S. 75 (1807).

- ↑ Binney, Horace. The privilege of the writ of habeas corpus under the Constitution, Vol. 1, p. 34 (1862).

- ↑ Bates, Edward. "Letter to the President" (July 5, 1861) reprinted in The War of the Rebellion...Additions and Corrections to Series 2, Volume 2, p. 20 (U.S. Government Printing Office, 1902).

- ↑ July 4th Message to Congress (July 4, 1861)

- ↑ Burlingame, Michael. Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Volume 2, p. 152 (JHU Press, 2013).

- ↑ Robinson, Kenton. "Historians won't convict Lincoln for suspension of habeas corpus", The Day (June 26, 2011).

- ↑ McGinty (2011) pp. 154-155

- ↑ McGinty (2011) pp. 156-158

- ↑ George Clarke Sellery, "Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus as viewed by Congress" (Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Wisconsin—Madison, 1907), pp. 11–26.

- 1 2 3 McGinty, Brian. Lincoln and the Court, pp. 84, 90, 304 (Harvard University Press 2009).

- ↑ White, Jonathan. Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War: The Trials of John Merryman, LSU Press, 2011. p. 106

- ↑ White, p. 107

- ↑ Don E. Fehrenbacher (1978/2001), the Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics, New York: Oxford, Chapter 23, "In the Stream of History", p. 574, and p. 715, n. 16.

- ↑ "Catron, John", in Webster's American Biographies (1979), Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster.

- ↑ Rollin C. Hurd, A Treatise on the Right of Personal Liberty and on the Writ of Habeas Corpus, revised with notes by Frank H. Hurd (Albany, 1876), 121n–122n.

- ↑ Hyman, Harold. The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United, p. 584 (Kermit Hall et al. eds., Oxford U. Press 2005).

- ↑ Hamdi v. Rumsfeld, 542 U.S. 507 (2004).

- ↑ Mitchell, p.207

- 1 2 3 4 http://articles.baltimoresun.com/2001-11-27/features/0111270102_1_habeas-fort-mchenry-lincoln-suspension

- ↑ Mitchell, p.291 Retrieved November 2012

- ↑ Howard, F. K. (Frank Key) (1863). Fourteen Months in American Bastiles. London: H. F. Mackintosh. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- ↑ Inside Lincoln's White House: The Complete Civil War Diary of John Hay, p. 28 (SIU Press, Michael Burlingame and John R. Turner Ettlinger eds. 1999).

- ↑ 12 Stat. 762.

- ↑ "History of the Federal Judiciary: Circuit Court of the District of Columbia: Legislative History". Federal Judicial Center. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ↑ Scharf, J. Thomas. "Suspension of Civil Liberties in Maryland:". Maryland State Archives. Retrieved 2008-05-16.

- ↑ Amnesty to Political or State Prisoners.

- ↑ White, Jonathan. Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War: The Trials of John Merryman, LSU Press, 2011. p. 106

- ↑ White, p. 107

- ↑ Proclamation 94.

- ↑ Sellery, pp. 34–51.

- ↑ Bruce Catton (1961), The Coming Fury, 1967 reprint, New York: Pocket Books, Ch. 6, "The Way of Revolution", Sec. 2, "Arrests and Arrests Alone", p. 360, ISBN 0-671-46989-4 ; Congressional Globe, 37th Congress, Third Session, Part 2, pp. 1372-1373, 1376.

References

- Brown, George William. Baltimore and the Nineteenth of April 1861 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1887; reprinted by Johns Hopkins University Press in 2001).

- Catton, Bruce (1961), The Coming Fury, 1967 reprint, New York: Pocket Books, ISBN 0-671-46989-4 .

- Fehrenbacher, Don Edward (1978), The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics, 2001 reprint, New York: Oxford, Pulitzer Prize in History.

- Howard, F. K. (Frank Key) (1863). Fourteen Months in American Bastiles. London: H.F. Mackintosh. Retrieved 18 August 2014.

- Hall, Kermit L. (Ed.) (1992). The Oxford Companion to the Supreme Court of the United States. Oxford University Press.

- Lincoln, Abraham (April 27, 1861). Letter to Winfield Scott. Cited in (1989) Lincoln: Speeches and Writings 237. New York: Library of America. (This is the letter in which Lincoln suspended habeas corpus.)

- Paludan, Phillip S. (1994). The Presidency of Abraham Lincoln. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0-7006-0671-8.

- Lossing, Benson John (1866), Pictorial Field Book of the Civil War, 1997 reprint, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins.

- McGinty, Brian (2011). The Body of John Merryman. Harvard University Press.

- Neely, Mark E. Jr. Lincoln and the Triumph of the Nation: Constitutional Conflict in the American Civil War. University of North Carolina Press.

- Poole, Patrick S. (1994). An Examination of Ex Parte Merryman.

- Rehnquist, William H. (1998). All the Laws but One: Civil Liberties in Wartime. New York: William Morrow & Co. ISBN 0-688-05142-1.

- Rehnquist, William, Chief Justice (1997). Civil Liberty and the Civil War.

- Taney, Roger B., Chief Justice (1861). Ex parte Merryman. — Note that while Taney is named as Chief Justice, this was not properly a Supreme Court case. [Not an en banc Supreme Court Case. Taney himself notes in the decision that it was "[b]efore the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, at Chambers." In the case itself it's noted that "a writ of habeas corpus was issued by the chief justice of the United States, sitting at chambers" - not as a judge of the Circuit Court. Taney then orders the case to be "filed and recorded in the circuit court of the United States for the district of Maryland". If he were sitting as Circuit judge there would have been no need to order the decision filed in Baltimore.]

- White, Jonathan W. (2011). Abraham Lincoln and Treason in the Civil War: The Trials of John Merryman. Baton Rouge: LSU Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-0-8071-4346-9.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Full text of Taney's opinion in the case at TeachingAmericanHistory.org.

- Ragsdale, Bruce. "Ex parte Merryman and Debates on Civil Liberties During the Civil War", Federal Judicial Center (2007).

- "Ex Parte Merryman, original case papers borrowed from the Federal District Court", Maryland Archives.