Frederick Cook

| Frederick Albert Cook | |

|---|---|

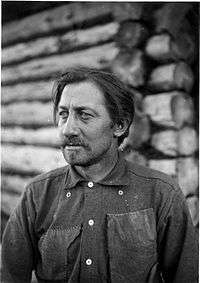

Cook с.1906 | |

| Born |

June 10, 1865 Callicoon, Sullivan County, New York |

| Died | August 5, 1940 (aged 75) |

| Education | Columbia University, M.D. (1890) |

| Spouse(s) |

1) Libby Forbes (d. 1890) 2) Marie Fidele Hunt (divorced 1923) |

| Children | Helene Cook |

Frederick Albert Cook (June 10, 1865 – August 5, 1940) was an American explorer, physician, and ethnographer, noted for his claim of having reached the North Pole on April 21, 1908. This was a year before April 6, 1909, the date claimed by the American explorer Robert Peary, and the accounts were disputed for several years.[1] His expedition did discover Meighen Island, the only discovery of an island in the American Arctic by a United States expedition.

After reviewing Cook's limited records, a commission of the University of Copenhagen ruled in December 1909 that he had not proven that he reached the pole. In 1911 Cook published a memoir of his expedition, continuing to assert their success. His 1906 account of having reached the summit of Denali has also been discredited.

Biography

Cook was born in Callicoon, Sullivan County, New York. His parents were Theodore A. Koch and Magdalena Long, recent German immigrants to the United States who anglicized their name by adopting the phonetic version of their German surname.

Cook attended Columbia University and received his M.D. from New York University Medical School in 1890.

Marriage and family

In 1889 Cook married Libby Forbes, who died in 1891. On his 37th birthday in 1902, he married Marie Fidele Hunt. They had one daughter Helene. In 1923 they were divorced.

Early expeditions

Cook was the surgeon on Robert Peary's 1891–1892 Arctic expedition, and on the Belgian Antarctic Expedition of 1897–1899 led by Adrien de Gerlache. He contributed greatly to saving the lives of the crew when their ship (the Belgica) was ice-bound during the winter, as they were not prepared for this. It was the first expedition to winter over in the Antarctic. To prevent scurvy, Cook went hunting in order to keep the crew supplied with fresh meat. When obtained from animals that make their own vitamin C (as most do), this could substitute for gaining the needed vitamin from citrus and other fruits and vegetables. Cook and Roald Amundsen, a fellow crew-member and Norwegian explorer, established a friendship and lifelong relationship of mutual respect.

In 1897, during this expedition, Cook twice visited Tierra del Fuego, where he met Anglican missionary Thomas Bridges. They discussed the Ona and Yahgan indigenous peoples, with whom Bridges had worked for two decades. During that time, he had prepared a grammar and dictionary in Yahgan (also called Yamana), of more than 30,000 words. Cook asked to borrow the manuscript for reference but did not return it before Bridges' death in 1898. Several years later Cook tried to publish the dictionary as his own work.[2]

In 1903 Cook led an expedition to Mount Denali, which resulted in his circumnavigation of the Denali range. He made a second expedition in 1906, and claimed then to have made the first ascent of that mountain (this claim is discussed at length below).

Arctic Club and Explorers Club

Cook was a founding member of two New York-based clubs supporting expeditions: the Arctic Club of America (1894–1913)[3] and the Explorers Club (1904–present). In 1907–1908 Cook served as the second president of the Explorers Club. He was expelled from both after his claim of having reached the North Pole in 1908 was rejected by a commission of the University of Copenhagen.[2]

1906 Mt. Denali climb

Cook claimed to have achieved the first summit of Denali (also known as Mt. McKinley) in September 1906, reaching the top with one other member of his expedition. Other members of the team (e. g., Belmore Browne), whom he had left lower on the mountain, expressed private doubts about this immediately. Cook's claims were not publicly challenged until the 1909 dispute with Peary over who had first reached the North Pole. Peary's supporters then publicly alleged that Cook's claim of ascent of Denali was fraudulent.

Unlike Hudson Stuck in 1913 (Ascent of Denali, 1914, photograph opposite p. 102) Cook took no photograph of the view from atop Denali. His photograph which he claimed to be of the summit was found to have been taken of a tiny peak[4] 19 miles away.

In late 1909 Ed Barrill, Cook's sole companion during the 1906 climb, signed an affidavit denying that they had reached the summit. Since the late 20th century, historians have found that he was paid by Peary supporters to do so. (Henderson, 2005) (Henderson writes that this fact was covered up at the time, but Bryce says that it was never a secret.)[5] Up until a month before, Barrill had consistently asserted that he and Cook had reached the summit. His 1909 affidavit included a map correctly locating what became called Fake Peak, featured in Cook's "summit" photo, and showing that he and Cook had turned back at the Gateway.[6]

Modern climber Bradford Washburn has gathered data, repeated the climbs, and taken new photos to evaluate Cook's 1906 claim. Between 1956 and 1995, Washburn and Brian Okonek identified the locations of most of the photographs Cook took during his 1906 Denali foray, and took new photos at the same spots. In 1997 Bryce identified the locations of the remaining photographs, including Cook's "summit" photograph;[7] none were taken anywhere near the summit. Washburn showed that none of Cook's 1906 photos were taken past the "Gateway" (north end of the Great Gorge), 12 horizontal bee-line miles from Denali and 3 miles below its top.

An expedition by the Mazama Club in 1910 reported that Cook's map departed abruptly from the landscape at a point when the summit was still 10 miles distant. Critics of Cook's claims have compared Cook's map of his alleged 1906 route with the landscape of the last 10 miles.[8] Cook's descriptions of the summit ridge are variously claimed to bear no resemblance to the mountain[9] and to have been verified by many subsequent climbers.[10] But, in the 1970s, climber Hans Waale found a route which fit Cook's narrative and descriptions.[11] Three decades later, in 2005 and 2006, this route was successfully climbed by a group of Russian mountaineers.[12]

No evidence of Cook's purported journey between the "Gateway" and the summit has been found. His claim to have reached the summit is not supported by his photos' vistas, his two sketch maps' markers, and peak-numberings for points attained,[13] nor by his compass bearings, barometer readings, route-map or camp trash. But, samples of all such evidence have been found short of the Gateway.[14]

North Pole

After the Mount Denali expedition, Cook returned to the Arctic in 1907. He planned to attempt to reach the North Pole, although he did not announce his intention until August 1907, when he was already in the Arctic. He left Annoatok, a small settlement in the north of Greenland, in February 1908. Cook claimed that he reached the pole on April 22, 1908 after traveling north from Axel Heiberg Island, taking with him only two Inuit men, Ahpellah and Etukishook. On the journey south, he claimed to have been cut off from his intended route to Annoatok by open water. Living off local game, his party was forced to push south to Jones Sound, spending the open water season and part of the winter on Devon Island. From there they traveled north, eventually crossing Nares Strait to Annoatok on the Greenland side in the spring of 1909. They said they almost died of starvation during the journey.

Cook and his two companions were gone from Annoatok for 14 months, and their whereabouts in that period is a matter of intense controversy. In the view of Canadian historian Pierre Berton (Berton, 2001), Cook's story of his trek around the Arctic islands is probably legitimate. Other writers have relied on later accounts told by Cook's companions to investigators, who seemed to present another view.

There are striking similarities between Ahpellah and Etukishook's sketched route of their journey south, and the route taken by the fictional shipwrecked explorers in Jules Verne's novel, The Adventures of Captain Hatteras. For example, the route the two Inuit traced on a map goes over both the Pole of Cold and the wintering site of the fictional expedition. Both expeditions went to the same area of Jones Sound in hopes of finding a whaling ship to take them to civilization. For details, see Osczevski (2003). Frederick Cook and the Forgotten Pole.

Cook's claim was initially widely believed. But it was disputed by Cook's rival polar explorer Robert Peary, who claimed to have reached the North Pole in April 1909. Cook initially congratulated Peary for his achievement, but Peary and his supporters launched a campaign to discredit Cook. They enlisted the aid of socially prominent persons outside the field of science, such as football coach Fielding H. Yost (as related in Fred Russell's 1943 book, I'll Go Quietly).

Cook never produced detailed original navigational records to substantiate his claim to have reached the North Pole. He said that his detailed records were part of his belongings, contained in three boxes, which he left at Annoatok in April 1909. He had left them with Harry Whitney, an American hunter who had traveled to Greenland with Peary the previous year, because of having insufficient manpower for a second sledge for his 700-mile journey south to Upernavik. When Whitney tried to bring Cook's boxes with him on his return to the USA on Peary's ship Roosevelt in 1909, Peary refused to allow them on board. So Whitney left Cook's boxes in a cache in Greenland. They were never found.

On December 21, 1909, a commission at the University of Copenhagen, after having examined evidence submitted by Cook, ruled that his records did not contain proof that the explorer reached the Pole.[15] (Peary refused to submit his records for review by such a third party, and for decades the National Geographic Society, which held his papers, refused researchers access to them.)

Cook intermittently claimed he had kept copies of his sextant navigational data, and in 1911 published some.[16] These have an incorrect solar diameter.[17] Ahwelah and Etukishook, Cook's Inuit companions, gave seemingly conflicting details about where they had gone with him. The major conflicts have been resolved in the light of improved geographical knowledge.[18] Whitney was convinced that they had reached the North Pole with Cook, but was reluctant to be drawn into the controversy.

The Peary expedition's people (primarily Matthew Henson, who had a working knowledge of Inuit, and George Borup, who did not) claimed that Ahwelah and Etukishook told them that they had traveled only a few days' journey from land. A map allegedly drawn by Ahwelaw and Etukishook correctly located and accurately depicted then-unknown Meighen Island, which strongly suggests that they visited it as they claimed.[19][20] A genuine Cook discovery, Meighen Island is the only island discovered by a United States expedition in the American arctic.[21] For more detail see Bryce, 1997 and Henderson, 2005.

The conflicting claims of Cook and Peary prompted Roald Amundsen to take extensive precautions in navigation during his South Pole expedition so there could be no doubt concerning attainment of the pole if successful. See Polheim. (Amundsen also had the advantage of traveling over a continent. He left unmistakable evidence of his presence at the South Pole, whereas any ice on which Cook might or might not have camped would have drifted many miles in the year between the competing claims.)

At the end of his 1911 memoir, Cook wrote: "I have stated my case, presented my proofs. As to the relative merits of my claim, and Mr Peary's, place the two records side by side. Compare them. I shall be satisfied with your decision."

Failed explorer reputation

Cook's reputation never recovered. While Peary's North Pole claim was widely accepted for most of the 20th century, it has been discredited by a variety of reviewers, including the National Geographic Society which long supported him. Cook spent the next few years defending his claim and threatening to sue writers who said that he had faked the trip. Researching the complicated story of the conflicting claims, the writer Robert Bryce began to see how the men's personalities and goals were in contrast, and set them against the period of the Gilded Age.[22] He believes that Cook, as a physician and ethnographer, cared about the people on his expedition and admired the Inuit. Bryce writes that Cook

- "genuinely loved and hungered for the real meat of exploration-mapping new routes and shorelines, learning and adapting to the survival techniques of the Eskimos, advancing his own knowledge-and that of the world-for its own sake."[22]

But he could not find supporters to help finance the expeditions without a goal that was more flashy. There was tremendous pressure on each man to be the first to reach the Pole, in order to gain support for continued expeditions.

Fraud trial

In 1919, Cook started promoting startup oil companies in Fort Worth, Texas. In April 1923, Cook and 24 other Fort Worth oil promoters were indicted in a federal crackdown on fraudulent oil company promotions. Three of Cook’s employees pleaded guilty, but Cook insisted on his innocence, and was put on trial. Joining him in the trial was his head advertising copy writer S. E. J. Cox, who had been previously convicted of mail fraud in connection with his own oil company promotions. Among other deceptive practices, Cook was charged with paying dividends from stock sales, rather than from profits. Cook’s attorney was former politician Joseph Weldon Bailey, who clashed frequently with the judge. The jury found Cook guilty on 14 counts of fraud, and in November 1923, Judge Killits sentenced Cook and 13 other oil company promoters to prison terms. Cook drew the longest sentence, 14 years 9 months. His attorney appealed the verdict, but the conviction was upheld.[23]

Cook was imprisoned until 1930. Roald Amundsen, who believed he owed his life to Cook's extrication of the Belgica, visited him several times. Cook was pardoned by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1940, ten years after his release and shortly before his death on August 5 of that year.

North Pole claims

Since the late 20th century, Peary's account of reaching the pole has encountered renewed scrutiny (Rawlins, 1973; Herbert, 1988; Berton, 2001; Henderson, 2005). Which man, if either, was first to reach the North Pole is subject to popular controversy in media. But, professionals widely accept that both of Cook's claims have been almost unanimously rejected for nearly a century.[24] In contrast, analyses presented by modern authors as addenda in the 2001 reprint of Cook's "My Attainment of the Pole"[25] refute earlier publications, and provide detailed evidence that it is likely Cook did reach the pole, as he claimed, or that in any case arguments to the contrary put forward by Peary and his supporters are readily disputed. These additional materials also chronicle the long and acrimonious disputes put forward by Peary in his attempts to discredit Cook.

Death

Frederick Cook died of a cerebral hemorrhage on August 5, 1940. His remains are at the Chapel of Forest Lawn Cemetery, Buffalo.

Representation in other media

- Cook is featured as a major character in the novel, The Navigator of New York (2003), by Wayne Johnston.

- The TV Movie, "Cook & Peary: The Race to the Pole" (1983), has Richard Chamberlain as Frederick Cook.

- Cook is also portrayed by Brian Dennehy in the 1985 British mini-series "The Last Place on Earth", the story of the Scott-Amundson competition to be the first to reach the South Pole.

- Cook appears in the 1911 film, "The Truth About the Pole,"[26] directed by Wilbert Melville. An ad for the film describes it as "An absorbing story of the Arctics Enacted by Dr. Frederick A Cook and a notable supporting cast." Release by North Pole Picture Co. No listing of the film on IMDB, so may be a lost film.

Notes

- ↑ Henderson, B. 2009, pp. 58–69

- 1 2 "Cook Tried to Steal Parson's Life Work", New York Times, 21 May 1910, accessed 3 October 2013

- ↑ "Finding aid to the Arctic Club of America" (PDF). The Explorers Club. Retrieved 2015-07-17.

- ↑ An aerial photograph by Bradford Washburn (Bryce (1997) DIO, volume 7, number 2, page 40) dramatizes the mountain-versus-molehill contrast of claim-versus-reality.

- ↑ DIO, volume 9, number 3, page 129, note 18

- ↑ R. Bryce, Bryce (1997) DIO, volume 7, number 2, page 57

- ↑ Compare rock-by-rock the left side of Cook's 1906 "summit" photo to the corresponding parts of the 1957 photo by Adams Carter and Bradford Washburn. Photos juxtaposed at Bryce (1999) DIO, volume 9, number 3, page 116. Compare also the background features in Cook's "summit" photo versus those in his own photo taken a few minutes later (towards the same direction) from the top of Fake Peak: Bryce (1997) DIO, volume 7, number 2, figure 4 versus figure 18; detailed-blowup comparisons in figures 6 and 8.

- ↑ Bryce (1997) DIO, volume 7, number 3, page 96 versus page 97

- ↑ Washburn, Bradford; Peter Cherici (2001). The Dishonorable Dr. Cook: Debunking the Notorious Mount McKinley Hoax. Seattle: Mountaineers Books. OCLC 47054650.

- ↑ Henderson (2005) p.282

- ↑ Bryce (1997) DIO p.73

- ↑ "Following the traces of Dr. Frederick Cook", SH Paro

- ↑ Bryce (1997) DIO pages 60–61

- ↑ Bryce (1999) DIO, volume 9, number 3, pages 124–125

- ↑ "University Finds That Cook's Papers Contain no Proof That He Reached the North Pole" (PDF). The New York Times. December 22, 1909. Retrieved 2011-12-20.

- ↑ F. Cook, My Attainment of the Pole, 1911, pages 258 and 274. Cook's first account of what he left with Whitney did not mention data, and Whitney knew of no data in what was left with him. See Rawlins, 1973, pages 87, 166, 301–302.

- ↑ Rawlins, Norwegian Journal of Geography (Oslo University), volume 26, pages 135–140, 1972

- ↑ Osczevski, R. J. (2003)Arctic Vol. 56, no. 4

- ↑ Osczevski, R. J.(2003a) "Frederick Cook and the Forgotten Pole," Arctic, vol 56, no. 2 pp. 207–217

- ↑ Rawlins, 1973, Chapter 6.

- ↑ Discoveries: "Meighen Island", DIOI

- 1 2 Ken Ringle, review: "Cook & Peary - The Polar Controversy Resolved", Backsights, 1997, published by Surveyors Historical Society, accessed 3 October 2013

- ↑ Roger Olien, “Doctor Frederick A. Cook and the Petroleum Producers’ Association,” Journal of the West, 1989, v.28 n.4 p.33-36.

- ↑ Silverberg, Robert (2007) Scientists and Scoundrels, Ch.7

- ↑ Russell W. Gibbons, (ed.), 90th Anniversary Edition, Polar Publishing Company, April, 2001.

- ↑ https://archive.org/stream/moviwor08chal#page/553/mode/1up

References

- Fred A. Cook: Meine Eroberung des Nordpols - übersetzt von Erwin Volckmann. 1912. Alfred Janssen Verlag - Hamburg und Berlin

- Berton, Pierre (2001). The Arctic Grail. Anchor Canada (originally published 1988). ISBN 0-385-65845-1. OCLC 46661513.

- Bryce, Robert M. (1997). Cook & Peary: The Polar Controversy, Resolved. Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-0317-7. OCLC 35280718.

- Bryce, Robert M. (December 1997). "The Fake Peak revisited" (PDF). DIO. 7 (3): 41–76. ISSN 1041-5440. OCLC 18798426.

- Henderson, Bruce (2005). True North: Peary, Cook, and the Race to the Pole. W. W. Norton and Company. ISBN 0-393-32738-8. OCLC 63397177.

- Henderson, B. (April 2009). "Cook vs. Peary". Smithsonian.

- Osczevski, Randall J. (2003). "Frederick Cook and the Forgotten Pole". Arctic. 56 (2): 207–217. doi:10.14430/arctic616. ISSN 0004-0843. OCLC 108412472.

- Rawlins, Dennis (1973). Peary at the North Pole, Fact or Fiction?. Luce. ISBN 0-88331-042-2.

- Robinson, Michael (2006). The Coldest Crucible: Arctic Exploration and American Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-72184-1.

- Silverberg, Robert (2007). Scientists and Scoundrels. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-5989-1.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of a 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article about Frederick Cook. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Frederick Cook. |

- Frederick A. Cook Society

- Frederick A. Cook: from Hero to Humbug

- Works by Frederick A. Cook at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Frederick Cook at Internet Archive