French Parliament

| French Parliament Parlement français | |

|---|---|

|

14th French Parliament of the Fifth French Republic | |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Houses |

Senate National Assembly |

| Leadership | |

President of the French Republic |

François Hollande, PS |

| Structure | |

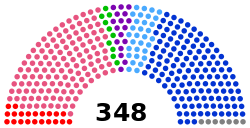

| Seats |

925 348 Senators 577 Deputies |

| |

Senate political groups |

Communist Group (20) Socialist Group (128) Europe Écologie–The Greens (12) European Democratic and Social Rally (18) Union of Democrats and Independents - UC (32) Republican Group (131) Non-Registered (7) |

| |

National Assembly political groups |

Socialist Group (left) (295) |

| Elections | |

Senate voting system | Indirect election |

National Assembly voting system | Two-round system |

Senate last election | 28 September 2014 |

National Assembly last election | 10 & 17 June 2012 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

| Château de Versailles | |

| Website | |

| French Parliament Website | |

The French Parliament (French: Parlement français) is the bicameral legislature of the French Republic, consisting of the Senate (Sénat) and the National Assembly (Assemblée nationale). Each assembly conducts legislative sessions at a separate location in Paris: the Palais du Luxembourg for the Senate and the Palais Bourbon for the National Assembly.

Each house has its own regulations and rules of procedure. However, they may occasionally meet as a single house, the French Congress (Congrès du Parlement français), convened at the Palace of Versailles, to revise and amend the Constitution of France.

Organization and powers

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of France |

|

|

Related topics |

| France portal |

Parliament meets for a single, nine-month session each year. Under special circumstances the President can call an additional session. While parliamentary power has been diminished since the Fourth Republic, the National Assembly can still cause a government to fall if an absolute majority of the assemblymen votes a motion of no confidence. As a result, the government normally is from the same political party as the Assembly and must be supported by a majority there to prevent a vote of no-confidence.

However, the President appoints the Prime Minister and the ministers and is under no constitutional, mandatory obligation to make those appointments from the ranks of the parliamentary majority party; this is a safe-guard specifically introduced by the founder of the Fifth Republic, Charles De Gaulle, to prevent the disarray and horse-trading caused by the Third and Fourth Republics parliamentary regimes; in practice the prime minister and ministers do come from the majority although President Sarkozy did appoint Socialist ministers or secretary of state-level junior ministers to his government. Rare periods during which the President is not from the same political party as the Prime Minister are usually known as cohabitation. The President rather than the prime minister heads the Cabinet of Ministers.

The government (or, when it sits in session every Wednesday, the cabinet) has a strong influence in shaping the agenda of Parliament. The government also can link its term to a legislative text which it proposes, and unless a motion of censure is introduced (within 24 hours after the proposal) and passed (within 48 hours of introduction – thus full procedures last at most 72 hours), the text is considered adopted without a vote. However, this procedure has been limited by the 2008 constitutional amendment. Legislative initiative rests with the National Assembly.

Members of Parliament enjoy parliamentary immunity.[1] Both assemblies have committees that write reports on a variety of topics. If necessary, they can establish parliamentary enquiry commissions with broad investigative power. However, the latter possibility is almost never exercised, since the majority can reject a proposition by the opposition to create an investigation commission. Also, such a commission may only be created if it does not interfere with a judiciary investigation, meaning that in order to cancel its creation, one just needs to press charges on the topic concerned by the investigation commission. Since 2008, the opposition may impose the creation of an investigation commission once a year, even against the wishes of the majority. However, they still can't lead investigations if there is a judiciary case going on already (or started after the commission was formed).

History

The French Parliament, as a legislative body, should not be confused with the various parlements of the Ancien Régime in France, which were courts of justice and tribunals with certain political functions varying from province to province and as to whether the local law was written and Roman, or customary common law.

The word "Parliament", in the modern meaning of the term, appeared in France in the 19th century, at the time of the constitutional monarchy of 1830–1848. It is never mentioned in any constitutional text until the Constitution of the 4th Republic in 1948. Before that time reference was made to "les Chambres" or to each assembly, whatever its name, but never to a generic term as in Britain. Its form – unicameral, bicameral, or multicameral – and its functions have taken different forms throughout the different political regimes and according to the various French constitutions:

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ In France, for nearly a century, the article 121 of the Penal Code punished with civic degradation all police officers, all prosecutors and all judges if they had caused, issued or signed a judgment, an order or a warrant, tending to a personal process or an accusation against a member of the Senate or of the legislative body, without the authorization prescribed by the Constitutions: Buonomo, Giampiero (2014). "Immunità parlamentari: Why not?". L’ago e il filo. – via Questia (subscription required)

- This article is based mainly on the article Parlement français from the French Wikipedia, retrieved on 13 October 2006.

Further reading

- Frank R. Baumgartner, "Parliament's Capacity to Expand Political Controversy in France", Legislative Studies Quarterly, Vol. 12, No. 1 (Feb. 1987), pp. 33–54

- Marc Abélès, Un ethnologue à l'Assemblée. Paris: Odile Jacob, 2000. An anthropological study of the French National Assembly, of its personnel, lawmakers, codes of behaviors and rites.

External links

- Official website (French)

- Site of the CHPP (Comité d'histoire parlementaire et politique) and of Parlement(s), Revue d'histoire politique (French)