Italian Parliament

| Italian Parliament Parlamento Italiano | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| Houses |

Senate of the Republic Chamber of Deputies |

| Leadership | |

President of the Senate | |

President of the Chamber | |

| Structure | |

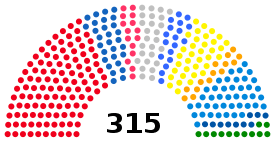

| Seats |

945 315 senators 630 deputies |

| |

Senate of the Republic political groups |

List

|

| |

Chamber of Deputies political groups |

List

|

| Elections | |

Senate of the Republic last election | 24–25 February 2013 |

Chamber of Deputies last election | 24–25 February 2013 |

| Meeting place | |

|

Chamber of Deputies—Palazzo Montecitorio Senate of the Republic—Palazzo Madama | |

| Website | |

| http://www.parlamento.it | |

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Italy |

| Constitution |

|

Legislature |

|

| Foreign relations |

|

Related topics |

The Italian Parliament (Italian: Parlamento Italiano) is the national parliament of the Italian Republic. It is a bicameral legislature with 945 elected members (parlamentari). It is composed of the Chamber of Deputies, with 630 members (deputati), and the Senate of the Republic, with 315 members (senatori). Both houses have the same duties and powers, and the Constitution does not make distinctions between them. But, because the President of the Senate stands in the role of Head of State when the President of the Republic needs to be replaced, the Senate is traditionally considered the upper house.

Function of the Parliament

The Parliament is the representative body of the citizens in the republican Institutions, and act accordingly.

By the Republican Constitution of 1948, the two Houses of the Italian Parliament possess the same rights and powers: this particular form of parliamentary democracy (the so-called perfect bicameralism) has been coded in the current form since the adoption of the Albertine Statute and resurged after the dismissal of the fascist dictatorship of the 1920s and 1930s during World War II.

The two Houses are independent from one another and never meet jointly except under circumstances specified by the Constitution. The House of Deputies has 630 members, while the Senate has 315 elected members and a small number of life senators: former Presidents of the Republic and up to five members appointed by the President for having contributed to the Country high achievement in the social or scientific field. As of February 2016 there are six life senators (of whom two are former presidents).

The main prerogative of the Parliament is the exercise of legislative power, that is the power to enact laws. For a text to become law, it must receive the vote of both Houses independently in the same form. A bill is discussed in one of the Houses, amended, and approved or rejected: if approved, it is passed to the other House, which can amend it and approve or reject it. If approved without amendments, the text is promulgated by the President of the Republic and becomes law. If approved with amendments, it is passed back to the originating House, which can approve the bill as amended, in which case the law is promulgated, or reject it.

The Parliament votes support to the Government,[1] which is appointed by the President of the Republic and, since 1994, usually led by the leader of the coalition winning the elections, while during the so-called First Republic it was chosen by the secretaries of major parties. The Government must receive a support vote by both Houses before being officially in power, and the Parliament can request a new vote of support at any moment if a quota of any House so requests. Should a Government fail to obtain a vote, it must resign; if it does, either a new Government is formed or the President of the Republic can dissolve the Houses and new elections are held.

The Parliament in joint session of both Houses elects the President of the Republic (in this case, 58 regional delegates are added), five (one third) members of the Corte Costituzionale and one third of the Superior Council of Judiciary. It can vote to decide an accusation of high treason or attack to the Constitution against the President of the Republic (though this situation has never occurred).

Electoral system

The Italian Electoral law of 2015, officially Law 6 May 2015, no. 52,[2] colloquially known by the nickname Italicum, given to it in 2014 by the Democratic Party secretary and subsequently head of government Matteo Renzi, who was its main proponent (until the end of January 2015 with the support of Forza Italia's leader Silvio Berlusconi) provides for a two-round system based on party-list proportional representation, corrected by a majority bonus and a 3% election threshold. Candidates run for election in 100 multi-member constituencies with open lists, except for a single candidate chosen by each party who is the first to be elected.

The law, which came into force on 1 July 2016, regulates the election of the Chamber of Deputies, replacing the previous electoral law of 2005, modified by the Constitutional Court in December 2013 after judging it partly unconstitutional.[3] By the time the law will come into force, the upper house is expected to have become a body representing regions, with greatly reduced powers, thus making a reform of its electoral system unnecessary.

Overseas constituency

The Italian Parliament is one of the few legislatures in the world to reserve seats for those citizens residing abroad. There are twelve such seats in the Chamber of Deputies and six in the Senate.[4]

Membership

Senate

The current membership of the Italian Senate, following the latest political elections of 24 and 25 February 2013:

| Coalition | Party | Seats | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pier Luigi Bersani: Italy. Common Good |

Democratic Party (PD) | 111 | ||

| Left Ecology Freedom (SEL) | 7 | |||

| South Tyrolean People's Party (SVP) | 2 | |||

| Trentino Tyrolean Autonomist Party (PATT) | 1 | |||

| Union for Trentino (UPT) | 1 | |||

| The Megaphone – Crocetta List (IM-LC) | 1 | |||

| Total | 123 | |||

| Silvio Berlusconi: Centre-right coalition |

The People of Freedom (PdL) | 98 | ||

| Lega Nord (LN) | 18 | |||

| Great South (GS) | 1 | |||

| Total | 117 | |||

| Beppe Grillo: Five Star Movement (M5S) | 54 | |||

| Mario Monti: With Monti for Italy | 19 | |||

| Associative Movement Italians Abroad (MAIE) | 1 | |||

| Aosta Valley coalition (VdA) | Valdostan Union (UV) | 1 | ||

| Total | 315 | |||

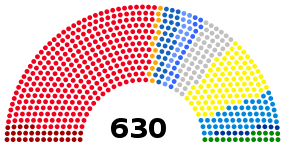

Chamber of Deputies

| Coalition | Party | Seats | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pier Luigi Bersani: Italy. Common Good |

Democratic Party (PD) | 297 | ||

| Left Ecology Freedom (SEL) | 37 | |||

| Democratic Centre (CD) | 6 | |||

| South Tyrolean People's Party (SVP) | 5 | |||

| Total | 345 | |||

| Silvio Berlusconi: Centre-right coalition |

The People of Freedom (PdL) | 98 | ||

| Lega Nord (LN) | 18 | |||

| Brothers of Italy (FdI) | 9 | |||

| Total | 125 | |||

| Beppe Grillo: Five Star Movement (M5S) | 109 | |||

| Mario Monti: With Monti for Italy |

Civic Choice (SC) | 37[lower-alpha 1] | ||

| Union of Christian and Centre Democrats (UDC) | 8 | |||

| With Monti for Italy (SC abroad) | 2 | |||

| Total | 47 | |||

| Associative Movement Italians Abroad (MAIE) | 2 | |||

| South American Union Italian Emigrants (USEI) | 1 | |||

| Aosta Valley coalition (VdA) | Edelweiss (SA) | 1 | ||

| Total | 630 | |||

As illustrated by the bars above, the Bersani-led coalition won the plurality in the nationwide election with a 0.4% lead over the nearest coalition, and thus - as defined by the Italian election law - was granted a majority bonus equal to an automatic 55% of the seats in the Chamber of Deputies.

Autodichia

The buckler so fallen on Italian Chambers, far from protecting them, revealed itself counterproductive to the image of the parliamentary institution[7]

In some matters (employment et al.) Italian Chambers act as judicial authority (without using external courts).[8] The order no. 137 of 2015 the Italian Constitutional Court[9] - agreeing to discuss again the same appeal on Lorenzoni case,[10] dismissed one year before - has recognized the possibility that such exercise could be in violation of the powers of Judiciary.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Parliament of Italy. |

- Constituent Assembly of Italy

- Italian Parliament (1928–1939)

- Politics of Italy

- Prime Minister of Italy

- Roman Senate

Notes

- ↑ Incl. the Union for Trentino (UPT) party leader Lorenzo Dellai, who decided not to submit his own party list for the Monti-coalition, but opted to be a direct part of the Civic Choice list.[5][6]

References

- ↑ Against the mingling of confidence vote and legislative process see (Italian) D. Argondizzo and G. Buonomo, Spigolature intorno all’attuale bicameralismo e proposte per quello futuro, in Mondoperaio online, 2 aprile 2014.

- ↑ (Italian) LEGGE 6 maggio 2015, n. 52.

- ↑ (Italian) Riforma elettorale

- ↑ "Presentazione delle candidature per la circoscrizione estero" [Submission of nominations for the constituency abroad]. Ministry of the Interior of Italy.

- ↑ "List Monti in Trentino: Lorenzo Dellai and candidates from Societa' Civile" (in Italian). l'Adige. 9 January 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ "Regional elections, the idea of coalition wins" (in Italian). l'Adige. 26 February 2013. Retrieved 28 February 2013.

- ↑ Buonomo, Giampiero (1998). "L'ultima tappa della giurisprudenza sugli interna corporis: la sentenza Calderoli". Giustamm.it. – via Questia (subscription required)

- ↑ According to the European Court of Human rights, in Italy "«autodichia», c'est-à-dire l'autonomie normative du Parlement" (judgement 28 April 2009, Savino and others v. Italy).

- ↑ http://www.ilfattoquotidiano.it/2015/07/07/consulta-ammissibile-il-conflitto-di-attribuzione-tra-poteri-dello-stato/1853996/

- ↑ See Giampiero Buonomo, Lo scudo di cartone, 2015, Rubbettino Editore, p. 224 (§ 5.5: La sentenza Lorenzoni), ISBN 9788849844405.

- Gilbert, Mark (1995). The Italian Revolution: The End of Politics, Italian Style?.

- Koff, Sondra; Stephen P. Koff (2000). Italy: From the First to the Second Republic.

- Pasquino, Gianfranco (1995). "Die Reform eines Wahlrechtssystems: Der Fall Italien". Politische Institutionen im Wandel.