George Peabody

| George Peabody | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

February 18, 1795 South Danvers, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died |

November 4, 1869 (aged 74) London, England |

| Resting place | Harmony Grove Cemetery, Salem, Massachusetts |

| Occupation | Financier, banker, entrepreneur |

| Net worth | USD $16 million at the time of his death (approximately 1/556th of US GNP)[1] |

| Religion | Unitarian |

| Parent(s) | Thomas Peabody and Judith Dodge |

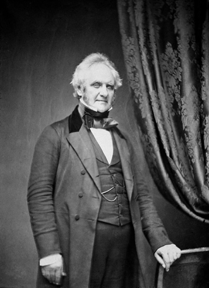

George Peabody (/ˈpiːbədi/ PEE-bə-dee;[2] February 18, 1795 – November 4, 1869) was an American-British financier widely regarded as the "father of modern philanthropy."

Born poor in Massachusetts, Peabody went into business in dry goods and later in banking. In 1837, he moved to London, then the capital of world finance, where he became the most noted American banker and helped to establish the young country's international credit. Having no son of his own to whom to pass on his business, Peabody took on Junius Spencer Morgan as a partner in 1854, and their joint business would go on to become J.P. Morgan & Co. after Peabody's 1864 retirement.

In his old age, Peabody won worldwide acclaim for his philanthropy. He founded the Peabody Trust in Britain and the Peabody Institute and George Peabody Library in Baltimore, and was responsible for many other charitable initiatives. For his generosity, he was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal and made a Freeman of the City of London, among many other honors.

Biography

Peabody was born in 1795 what was then South Danvers (now Peabody), Massachusetts. His family had Puritan ancestors in the state, but were poor. As one of 7 children, George suffered some deprivations during his childhood, and was only able to attend school for a few years.[3] These factors influenced his later devotion to both thrift and philanthropy.

In 1816, he moved to Baltimore, where he made his career and would live for the next 20 years. He established his residence and office in the old Henry Fite House, and became a businessman and financier.

At that time London, Amsterdam, Paris and Frankfurt, were at the center of international banking and finance. As all international transactions were settled in gold or gold certificates, a developing nation like the United States had to rely upon agents and merchant banks to raise capital through relationships with merchant banking houses in Europe. Only they held the quantity of reserves of capital necessary to extend long-term credit to a developing economy like that of the US.

Peabody first visited England in 1827, seeking to use his firm and his agency to sell American states' bond issues, to allow the States' to raise capital for their various programs of "internal improvements" (principally the transportation infrastructure, such as roads, railroads, docks and canals). Over the next decade Peabody made four more trans-Atlantic trips, establishing a branch office in Liverpool. Later he established the banking firm of "George Peabody & Company" in London. In 1837, he took up permanent residence in London, where he lived for the rest of his life.

Although Peabody was briefly engaged in 1838 (and later allegedly had a mistress in Brighton, England, who bore him a daughter), he never married.[4] Ron Chernow describes him as "homely", with "a rumpled face ... knobby chin, bulbous nose, side whiskers, and heavy-lidded eyes."[3]

Peabody frequently entertained and provided letters of introduction for American businessmen visiting London, and became known for the Anglo-American dinners he hosted in honor of American diplomats and other worthies, and in celebration of the Fourth of July. In 1851, when the US Congress refused to support the American section at the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace, Peabody advanced £3000 to improve the exhibit and uphold the reputation of the United States. In 1854, he offended many of his American guests at a Fourth of July dinner when he chose to toast Queen Victoria before US President Franklin Pierce; Pierce's future successor, James Buchanan, then Ambassador to London, left in a huff.[5] At around this time, Peabody began to suffer from rheumatoid arthritis and gout.[6]

In February 1867, on one of several return visits to the United States, and at the height of his financial success, Peabody was suggested by Francis Preston Blair, an old crony of President Andrew Jackson and an active power in the smoldering Democratic Party as a possible Secretary of the Treasury in the cabinet of President Andrew Johnson. At about the same time, Peabody was also mentioned in newspapers as a future presidential candidate. Peabody described the presidential suggestion as a "kind and complimentary reference", but considered that at age 72, he was too old for either office.[7]

He died in London on November 4, 1869, aged 74, at the house of his friend Sir Curtis Lampson. At the request of the Dean of Westminster, and with the approval of Queen Victoria, Peabody was given a temporary burial in Westminster Abbey.[8]

His will provided that he be buried in the town of his birth, Danvers, Massachusetts. Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone arranged for Peabody's remains to be returned to America on HMS Monarch, the newest and largest ship in the Royal Navy, arriving at Portland, Maine, where his remains were received by US Admiral David Farragut. He was laid to rest in Harmony Grove Cemetery, in Salem, Massachusetts, on February 8, 1870. Peabody's death and the pair of funerals were international news, through the newly completed trans-Atlantic underwater telegraph cable. Hundreds of people participated in the ceremonies and thousands more attended or observed.[9]

Business

While serving as a volunteer in the War of 1812, Peabody met Elisha Riggs, who, in 1814, provided financial backing for what became the wholesale dry goods firm of Riggs, Peabody & Co., specializing in importing dry goods from Britain. Branches were opened in New York and Philadelphia in 1822. Riggs retired in 1829, and the firm became Peabody, Riggs & Co., with the names reversed as Peabody became the senior partner.

Peabody first visited England in 1827 to purchase wares, and to negotiate the sale of American cotton in Lancashire. He subsequently opened a branch office in Liverpool, and British business began to play an increasingly important role in his affairs. He appears to have had some help in establishing himself from William and James Brown, sons of another highly-successful Baltimore businessman, the Irishman Alexander Brown (founder of the venerable investment and banking firm of "Alex. Brown & Son" in 1801), who managed their father's Liverpool office, opened in 1810.

In 1837, Peabody took up residence in London, and the following year, he started a banking business trading on his own account.[10] The banking firm of "George Peabody and Company" was not, however, established until 1851.[11] It was founded to meet the increasing demand for securities issued by the American railroads, and – although Peabody continued to deal in dry goods and other commodities – he increasingly focused his attentions on merchant banking, specializing in financing governments and large companies.[10] The bank rose to become the premier American house in London.[10]

In Peabody's early years in London, American state governments were notorious for defaulting on their debts to British lenders, and as a prominent American financier in London, Peabody often faced scorn for America's poor credit. (On one occasion, he was even blackballed from membership in a gentlemen's club.) Peabody joined forces with Barings Bank to lobby American states for debt repayment, particularly his home state of Maryland. The campaign included printing propaganda and bribing clergy and politicians, most notably Senator Daniel Webster. Peabody made a significant profit when Maryland, Pennsylvania, and other states resumed payments, having previously bought up state bonds at a low cost.[12] Encyclopædia Britannica cites him as having "helped establish U.S. credit abroad."[13]

Peabody took Junius Spencer Morgan (father of J. P. Morgan) into partnership in 1854 to form Peabody, Morgan & Co., and the two financiers worked together until Peabody's retirement in 1864; Morgan had effective control of the business from 1859 on.[14] During the run on the banks of 1857, Peabody had to ask the Bank of England for a loan of £800,000: although rivals tried to force the bank out of business, it managed to emerge with its credit intact.

Following this crisis, Peabody began to retire from active business, and in 1864, retired fully (taking with him much of his capital, amounting to over $10,000,000, or £2,000,000). Peabody, Morgan & Co. then took the name J.S. Morgan & Co.. The former UK merchant bank Morgan Grenfell (now part of Deutsche Bank), international universal bank JPMorgan Chase and investment bank Morgan Stanley can all trace their roots to Peabody's bank.[15]

Philanthropy

Though thrifty, even miserly with his employees and relatives, Peabody gave generously to public causes.[16] He became the acknowledged father of modern philanthropy,[17][18][19][20] having established the practice later followed by Johns Hopkins, Andrew Carnegie, John D. Rockefeller and Bill Gates. In the United States, his philanthropy largely took the form of educational initiatives. In Britain, it took the form of providing housing for the poor.

In America, Peabody founded and supported numerous institutions in New England, the South, and elsewhere. In 1867–68, he established the Peabody Education Fund with $3.5 million to "encourage the intellectual, moral, and industrial education of the destitute children of the Southern States."[21][22] His grandest beneficence, however, was to Baltimore; the city in which he achieved his earliest success.

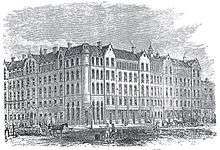

In April 1862, Peabody established the Peabody Donation Fund, which continues to this day as the Peabody Trust, to provide housing of a decent quality for the "artisans and labouring poor of London". The trust's first dwellings, designed by H. A. Darbishire in a Jacobethan style, were opened in Commercial Street, Spitalfields in February 1864.

George Peabody provided benefactions of well over $8 million, most of them in his own lifetime. Among the list are:

- 1852 The Peabody Institute (now the Peabody Institute Library),[23] Peabody, Mass: $217,000

- 1856 The Peabody Institute, Danvers, Mass (now the Peabody Institute Library of Danvers):[24] $100,000

- 1857 The Peabody Institute (now the Peabody Institute of the Johns Hopkins University), Baltimore: $1,400,000

- 1862 The Peabody Donation Fund, London: $2,500,000

- 1866 The Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University: $150,000

- 1866 The Peabody Museum of Natural History, Yale University: $150,000

- 1867 The Peabody Academy of Science, Salem, Mass: $140,000

- 1867 The Peabody Institute, Georgetown, District of Columbia: $15,000 (today the Peabody Room, Georgetown Branch, DC Public Library).

- 1867 Peabody Education Fund: $2,000,000

- 1875 George Peabody College for Teachers, now the Peabody College of Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tennessee. The funding came from the Peabody Education Fund

- 1877 Peabody High School, Trenton, Tennessee, established with funds provided by Peabody

- 1866 The Georgetown Peabody Library, the public library of Georgetown, Massachusetts

- 1866 The Thetford Public Library, the public library of Thetford, Vermont: $5,000

- 1901 The Peabody Memorial Library, Sam Houston State University, Texas

- 1913 George Peabody Building, University of Mississippi [25]

- 1913 Peabody Hall, housing the Department of Curriculum and Instruction, University of Arkansas:[26] $40,000

- 1913 Peabody Hall, housing the School of Education (now Philosophy and Religion), University of Georgia:[27] $40,000

- Peabody Hall, housing the college of Human Science and Education, Louisiana State University.

Recognition and commemoration

Peabody's philanthropy won him many admirers in his old age. He was praised by European luminaries such as Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone and author Victor Hugo, and Queen Victoria offered him a baronetcy, which he refused.[28]

In 1854, the Arctic explorer Elisha Kane named the waterway off the north-west coast of Greenland "Peabody Bay", in honor of Peabody, who had funded his expedition. The waterway was later renamed the Kane Basin, but Peabody Bay survives as the name of a smaller bay at the eastern side of the basin.[29]

On July 10, 1862 he was made a Freeman of the City of London, the motion being proposed by Charles Reed in recognition of his financial contribution to London's poor.[30] He became the first of only two Americans (the other being 34th President and General Dwight D. Eisenhower) to receive the award. A statue of him was unveiled by the Prince of Wales in 1869 next to the Royal Exchange, London, on the site of the former church of St Benet Fink (demolished 1842-6). On March 16, 1867, he was awarded the United States Congressional Gold Medal,[31] an Honorary Doctorate of Laws by Harvard University, and an Honorary Doctorate in Civil Law by Oxford University.[32] On March 24, 1867, Peabody was elected a member of the American Antiquarian Society[33]

Peabody's birthplace, South Danvers, Massachusetts, changed its name in 1868 to the town (now city) of Peabody, in honor of its favorite son. In 1869, the Peabody Hotel in Memphis, TN, was named in his memory. A number of Elementary and High Schools in the United States are named after Peabody.

A statue sculpted by William Wetmore Story stands next to the Royal Exchange in the City of London, unveiled by the Prince of Wales in July 1869: Peabody himself was too unwell to attend the ceremony, and died less than four months later.[34] A replica of the same statue, erected in 1890, stands next to the Peabody Institute, in Mount Vernon Park, part of the Mount Vernon neighborhood of Baltimore, Maryland.

In 1900, Peabody was one of the first 29 honorees to be elected to the Hall of Fame for Great Americans, located on what was then the campus of New York University (and is now that of Bronx Community College), at University Heights, New York.

His birthplace at 205 Washington Street in the City of Peabody is now operated and preserved as the George Peabody House Museum, a museum dedicated to interpreting his life and legacy. There is a blue plaque on the house where he died in London, No. 80 Eaton Square, Belgravia, erected in 1976.[35]

References

- ↑ Klepper, Michael; Gunther, Michael (1996), The Wealthy 100: From Benjamin Franklin to Bill Gates—A Ranking of the Richest Americans, Past and Present, Secaucus, New Jersey: Carol Publishing Group, p. xii, ISBN 978-0-8065-1800-8, OCLC 33818143

- ↑ This is the standard pronunciation in the United States, and presumably how Peabody himself pronounced his name. In Britain, however, the name of George Peabody himself, and of the Peabody Trust, is invariably pronounced as spelt, Pea-body /ˈpiːˈbɒdi/.

- 1 2 Chernow, Ron (2010-01-19). The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance. Grove/Atlantic, Inc. p. 4. ISBN 9780802198136.

- ↑ Parker 1995, pp. 29–33.

- ↑ Chernow, Ron (2010-01-19). The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance. Grove/Atlantic, Inc. p. 7. ISBN 9780802198136.

- ↑ Chernow, Ron (2010-01-19). The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance. Grove/Atlantic, Inc. p. 8. ISBN 9780802198136.

- ↑ Parker 1995, pp. 164–5, 203, 214.

- ↑ "Funeral of George Peabody at Westminster Abbey". The New York Times. 1869-11-13. p. 3.

As soon as the ceremony within the church was over the procession formed again, and advanced to a spot near the western entrance, where a temporary grave had been prepared... Here the body was deposited, and will remain until it is transported to America.

- ↑ Parker, Franklin (July 1966). "The Funeral of George Peabody". Peabody Journal of Education. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates (Taylor & Francis Group). 44 (1): 21–36. doi:10.1080/01619566609537382. JSTOR 1491421.

- 1 2 3 Chernow, Ron (2010-01-19). The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance. Grove/Atlantic, Inc. p. 5. ISBN 9780802198136.

- ↑ Burk (1989), p. 1

- ↑ Chernow, Ron (2010-01-19). The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance. Grove/Atlantic, Inc. pp. 5–7. ISBN 9780802198136.

- ↑ "George Peabody | American merchant, financier, and philanthropist". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- ↑ Chernow, Ron (2010-01-19). The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance. Grove/Atlantic, Inc. pp. 9–13. ISBN 9780802198136.

- ↑ Chernow, Ron (1990). The House of Morgan: an American banking dynasty and the rise of modern finance. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press. ISBN 0871133385.

- ↑ Chernow, Ron (2010-01-19). The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance. Grove/Atlantic, Inc. p. 9. ISBN 9780802198136.

- ↑ Bernstein, Peter (2007). All the Money in the World. Random House. p. 280. ISBN 0-307-26612-5.

Even before the Carnegies and Rockefellers became philanthropic legends, there was George Peabody, considered to be the father of modern philanthropy.

- ↑ The Philanthropy Hall of Fame, George Peabody

- ↑ Davies, Gill (2006). One Thousand Buildings of London. Black Dog Publishing. p. 179. ISBN 1-57912-587-5.

George Peabody (1795-1869)—banker, dry goods merchant, and father of modern philanthropy...

- ↑ "Peabody Hall Stands as Symbol of University's History". University of Arkansas. December 2009. Retrieved 2010-03-12.

George Peabody is considered by some to be the father of modern philanthropy.

- ↑ "George Peabody Library History". Johns Hopkins University. Retrieved 2010-03-12.

After the Civil War he funded the Peabody Education Fund which established public education in the South.

- ↑ Negro Year Book: An Annual Encyclopedia of the Negro .... 1913. p. 180.

- ↑ Peabodylibrary.org

- ↑ Danverslibrary.org

- ↑ http://catalog.olemiss.edu/university/buildings

- ↑ University Of Arkansas

- ↑

- ↑ Chernow, Ron (2010-01-19). The House of Morgan: An American Banking Dynasty and the Rise of Modern Finance. Grove/Atlantic, Inc. p. 14. ISBN 9780802198136.

- ↑ "Biography – KANE, ELISHA KENT – Volume VIII (1851-1860) – Dictionary of Canadian Biography". www.biographi.ca. Retrieved 2016-05-18.

- ↑ "London People: George Peabody". Retrieved 2010-03-12.

By 1867 Peabody had received honours from America and Britain, including being made a Freeman of the City of London, the first American to receive this honour.

- ↑ "Congressional Gold Medal Recipients". United States House of Representatives. Retrieved 10 May 2016.

- ↑ Parker 1995, p. 203.

- ↑ American Antiquarian Society Members Directory

- ↑ A detailed account of the commissioning, erection and reception of the statue appears in Ward-Jackson 2003, pp. 338–41.

- ↑ "George Peabody Blue Plaque". openplaques.org. Retrieved 23 November 2013.

Further reading

- Burk, Kathleen (1989). Morgan Grenfell 1838-1988: the biography of a merchant bank. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-828306-7.

- Burk, Kathleen (2004). "Peabody, George (1795–1869)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/21664.

- Curry, Jabez Lamar Monroe. A Brief Sketch of George Peabody: And a History of the Peabody Education Fund Through Thirty Years (Negro Universities Press, 1969).

- Hanaford, Phebe Ann (1870). The Life of George Peabody: Containing a Record of Those Princely Acts of Benevolence Which Entitle Him to the Esteem and Gratitude of All Friends of Education and the Destitute, Both in America, the Land of His Birth, and in England, the Place of His Death. B.B. Russell. Retrieved 10 November 2015.

- Hidy, Muriel E. George Peabody, merchant and financier: 1829-1854 (Ayer, 1978).

- Parker, Franklin (1995). George Peabody: A Biography (2nd ed.). Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 0-8265-1256-9., a major scholarly biography

- Ward-Jackson, Philip (2003). Public Sculpture of the City of London. Public Sculpture of Britain. 7. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. pp. 338–41. ISBN 0853239673.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of a 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article about George Peabody. |

Media related to George Peabody at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to George Peabody at Wikimedia Commons- Phillips Library, Peabody Essex Museum. Repository of 145 linear feet of Peabody's business and personal papers.