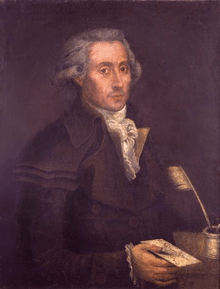

Georges Couthon

Georges Auguste Couthon (22 December 1755 – 28 July 1794) was a French politician and lawyer known for his service as a deputy in the Legislative Assembly during the French Revolution. Couthon was elected to the Committee of Public Safety on 30 May 1793 and served as a close associate of Maximilien Robespierre and Louis Antoine de Saint-Just until his arrest and execution in 1794 during the period of the Reign of Terror. Couthon played an important role in the development of the Law of 22 Prairial, which was responsible for a sharp increase in the number of executions of accused counter-revolutionaries.

Background

Couthon was born on 22 December 1755 in Orcet in the province of Auvergne. His father was a notary, his mother the daughter of a shopkeeper. Couthon, like generations of his family before him, was a member of the lower bourgeoisie. Following in his father’s footsteps, Couthon became a notary. The skills he acquired enabled him to to serve on the Provincial Assembly of Auvergne in 1787, his first experience of politics.[1] He was well-regarded by others as an honest, well-mannered individual.[2]

As the Revolution grew nearer, Couthon started to become disabiled due to advancing paralysis in both legs. While doctors diagnosed Couthon with meningitis in 1792, Couthon blamed his paralysis on the frequent sexual experiences of his youth; although he began treating his condition with mineral baths, he grew so weak by 1793 that he was confined to a wheelchair[3] driven by hand cranks via gears.[4] His political aspirations took him away from Orcet and to Paris, where he joined the Freemasons in 1790 in Clermont. While in Clermont, he became a fixture at its literary society, where he earned acclaim for his discussion on the topic of "Patience."[5] In 1791, Couthon became one of the deputies of the Legislative Assembly, representing Puy-de-Dôme.[6]

Deputy

In 1791, Couthon traveled to Paris to fulfill his duty as a deputy in the Legislative Assembly. He then joined the growing Jacobin Club of Paris. He chose to sit on the Left at the first meeting of the Assembly, but soon decided against associating himself with such radicals as he feared they were "shocking the majority."[7] He was a very proficient speaker, and there is evidence that he exploited his condition as a paraplegic in order to gain the ear of the Assembly on issues he found important.[8]

In September 1792, Couthon was elected to the National Convention. During a visit to Flanders, where he sought treatment for his health, he met and befriended Charles François Dumouriez, later writing praises of him to the Assembly, referring to him as "a man essential to us."[9] His relationship with Dumouriez caused Couthon to consider joining the Girondist faction of the Assembly briefly, but after the Girondist electors of the Committee of the Constitution refused Couthon a seat on the Committee in October 1792, he ultimately committed himself to the Montagnards and the inner group formed around Maximilien Robespierre - a man with whom he shared many opinions, especially on religious issues such as revolutionary dechristianization (to which he was opposed- see Cult of the Supreme Being)[10] Couthon became an enthusiastic supporter of the Montagnards and often echoed their opinions. At the Trial of Louis XVI in DEcember 1792, he argued loudly against the Girondist request for a referendum. He would go on to vote for the death sentence without appeal.[11] On 30 May 1793, Couthon was elected to the Committee of Public Safety, where he would work closely with Robespierre and Saint-Just in the planning of policy strategy and policing personnel.[12] Three days after rising to this position, Couthon was the first to demand the arrest of proscribed Girondists.[13]

Lyon

Growing unrest had been occurring in Lyon in late February and early May. By 5 July 1793, the National Convention determined the city of Lyon to be “in a state of rebellion”, and by September, the Committee of Public Safety decided to send representatives to Lyon to end the rebellion.[14] Couthon would be the representative that Lyon would surrender to on 9 October 1793. He was suspicious of the unrest in Lyon upon his arrival, and would not allow the Jacobins of the local administration to meet with one another, fearing an uprising.[15]

On 12 October 1793, the Committee of Public Safety passed a decree that they believed would make an example of Lyon. The decree specified that the city itself was to be destroyed. Following the decree, Couthon established special courts that would supervise the demolition of the richest homes in Lyon, leaving the homes of the poor untouched.[16] In addition to the demolition of the city, the decree dictated that the rebels and the traitors were to be executed. Couthon had difficulty accepting the destruction of Lyon and proceeded slowly with his orders. Eventually, he would find that he could not stomach the task at hand, and by the end of October, he requested the National Convention to send a replacement.[17] Republican atrocities in Lyon began after Couthon was replaced on 3 November 1793 by Jean Marie Collot d'Herbois, who would go on to condemn 1,880 Lyonnais by April 1794.[18]

Law of 22 Prairial

Following his departure from Lyon, Couthon returned to Paris, and on 21 December, he was elected president of the Convention. He contributed to the prosecution of the Hébertists and continued serving on the Committee of Public Safety for the next several months. On 10 June 1794 (22 Prairial Year II on the French Republican Calendar), Couthon drafted the Law of 22 Prairial with the aid of Robespierre. On the pretext of shortening proceedings, the law deprived the accused of the aid of counsel and of witnesses for their defense in the case of trials before the Revolutionary Tribunal.[19] The Revolutionary Tribunals were charged with quick verdicts of innocence or death for the accused brought before them.

Couthon proposed the law without consulting the rest of the Committee of Public Safety, as both Couthon and Robespierre expected that the Committee would not be receptive to it.[20] The Convention raised objections to the measure, but Couthon justified the measure by arguing that the political crimes oversaw by the Revolutionary Tribunals were considerably worse than common crimes because "the existence of free society is threatened." Couthon also famously justified the deprivation of the right to a counsel by declaring that the guilty have no right for a counsel and the innocents do not need any.[21]

Robespierre assisted Couthon in his arguments by subtly implying that any member of the Convention who objected to the new bill should fear being exposed as a traitor to the republic.[22] Both Couthon and Robespierre would be seen as dictators due to their vehement defense of the Law of 22 Prairial, and popular opinion would turn against them in the coming weeks.

The law passed, and the rate of executions promptly rose. In Paris alone, compared to an average of 5 executions that was the norm two months earlier (Germinal), 17 executions would take place daily during Prairial, with 26 occurring daily during the following month of Messidor.[23] Between the passing of the Law of 22 Prairial (10 June 1794) and the end of July 1794, 1,515 executions took place at the Place de la Revolution, more than half of the final total of 2,639 executions that occurred between March 1793 and August 1794.[24]

Thermidor

During the crisis preceding the Thermidorian Reaction, Couthon showed considerable courage, giving up a journey to Auvergne in order, as he wrote, that he might either die or triumph with Robespierre and liberty. Robespierre had disappeared from the political arena for an entire month because of a supposed nervous breakdown, and therefore did not realize that the situation in the Convention had changed. His last speech seemed to indicate that another purge of the Convention was necessary, though he refused to name names. In a panic of self-preservation, the Convention called for the arrest of Robespierre and his affiliates, including Couthon, Saint-Just and Robespierre's own brother, Augustin Robespierre.[25] Couthon was guillotined on 10 Thermidor alongside Robespierre, although it took the executioner fifteen minutes (amidst Couthon's screams of pain) to arrange him on the board correctly due to his paralysis.[26]

Legacy

Couthon, during the course of the French Revolution, had transitioned from an undecided young deputy to a strongly committed law maker. Aside from his actions in Lyon, it is perhaps the creation of the Law of 22 Prairial, and the number of individuals who would be executed due to the law, that has become his lasting legacy. Following the acceptance of Couthon’s new decree, executions increased from 134 people in early 1794 to 1,376 people between the months of June and July in 1794. The Law of 22 Prairial also allowed tribunals to target noblemen and members of the clergy with reckless abandon, as the accused no longer could call character witnesses on their behalf. Of the victims executed during June and July 1794, 38 percent were of noble descent and 26 represented the clergy. More than half of the victims came from the wealthier parts of the bourgeoisie. Couthon's lawmaking not only greatly increased the rate of executions across France, but also brought the Terror away from mere counter-revolutionary acts and closer to social discrimination than ever before.[27]

References

- ↑ Geoffrey Brunn, "The Evolution of a Terrorist: Georges Auguste Couthon." The Journal of Modern History 2, no. 3 (September 1930): 410, JSTOR 1898818

- ↑ R.R. Palmer, Twelve Who Ruled: The Year of the Terror in the French Revolution (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1941), 13

- ↑ Palmer, Twelve Who Ruled, 13-14

- ↑ The wheelchair is still preserved in the Carnavalet Museum. See "Fauteuil de Georges Couthon". Retrieved 2013-07-05.

- ↑ Palmer, Twelve Who Ruled, 13

- ↑ Brunn, "The Evolution of a Terrorist," 411.

- ↑ Bruun, “The Evolution of a Terrorist,” 416.

- ↑ Bruun, "The Evolution of a Terrorist," 413.

- ↑ Brunn, "The Evolution of a Terrorist," 420.

- ↑ Bruun, "The Evolution of a Terrorist," 422-423.

- ↑ Bruun, "The Evolution of a Terrorist," 427-428

- ↑ Colin Jones, The Longman Companion to the French Revolution (London: Longman Publishing Group, 1990), 90-91

- ↑ David Andress, The Terror: The Merciless War for Freedom in Revolutionary France (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005), 177

- ↑ David L. Longfellow, "Silk Weavers and the Social Struggle in Lyon during the French Revolution, 1789-94," French Historical Studies 12, no. 1 (Spring, 1981): 22, JSTOR 286305

- ↑ Longfellow, "Silk Weavers," 23

- ↑ William Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 1989), 253-254.

- ↑ Mansfield, Paul. "The Repression of Lyon 1793-4: Origins, Responsibility and Significance." French History, 1988: 74-101.

- ↑ Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution, 254

- ↑ "The Law of 22 Prairial Year II (10 June 1794)," George Mason University, http://chnm.gmu.edu/revolution/d/439/ (23 January 2012)

- ↑ Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution, 277.

- ↑ Les coupables n'y ont pas droit et les innocents n'en ont pas besoin cited from Compte Rendu Mission d’information sur les questions mémorielles of the French National Assembly.

- ↑ Simon Schama, Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution (New York: Vintage Books, 1989), 836-837.

- ↑ Schama, Citizens, 837.

- ↑ Doyle, The Oxford History of the French Revolution, 275.

- ↑ Jones, Colin. The Longman Companion to the French Revolution. London: Longman Publishing Group, 1990.

- ↑ Lenotre, G. Romances of the French Revolution. Translated by George Frederic William Lees. New York: William Heinemann: 1909.

- ↑ Doyle, The Oxford Dictionary of the French Revolution, 275

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Georges Couthon. |

- The 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica, in turn, gives the following references:

- Francisque Mége, Correspondance de Couthon ... suivie de l'Aristocrate converti, comédie en deux actes de Couthon, Paris: 1872.

- Nouveaux Documents sur Georges Couthon, Clermont-Ferrand: 1890.

- F. A. Aulard, Les Orateurs de la Legislative et de la Convention, (Paris, 1885–1886), ii. 425-443.

- R.R. Palmer, 12 Who Ruled: The Year of the Terror in the French Revolution , Princeton U. Press, 1970(reprint)

- Bruun, Geoffrey. “The Evolution of a Terrorist: Georges Auguste Couthon.” Journal of Modern History 2, no. 3 (1930), JSTOR 1898818.

- Doyle, William. “The Republican Revolution October 1791-January 1793.” In The Oxford History of the French Revolution. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Furet, François, and Mona Ozouf. “Committee of Public Safety.” In A Critical Dictionary of the French Revolution. Translated by Arthur Goldhammer. Harvard: Harvard University Press, 1989.

- Jones, Colin. The Longman Companion to the French Revolution. London: Longman Publishing Group, 1990.

- Kennedy, Michael L. The Jacobin Clubs in the French Revolution 1793-1795. New York: Berghahn Books, 2000.

- Kennedy, Michael L. The Jacobin Clubs in the French Revolution: The Middle Years. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988.

- Lenotre, G. Romances of the French Revolution. Translated by George Frederic William Lees. New York: William Heinemann: 1909.

- Schama, Simon. Citizens. New York: Vintage Books, 1989.

- Scott, Walter. The Miscellaneous Prose Works of Walter Scott. London: Whittaker and Co., 1835. 195.M1.

- The French Revolution. London: The Religious Tract Society, 1799.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.