State ownership

State ownership (also called public ownership and government ownership) refers to property interests that are vested in the state or a public body representing a community as opposed to an individual or private party.[1] State ownership may refer to ownership and control of any asset, industry, or enterprise at any level (national, regional, local or municipal); or to non-governmental public ownership. The process of bringing an asset into state ownership is called nationalization or municipalization. State ownership is one of the three major forms of property ownership, differentiated from private, cooperative and common ownership.[2]

In market-based economies, state-owned assets are frequently managed and operated as joint-stock corporations with a government owning either all or a controlling stake of the shares. This form is often referred to as a state-owned enterprise. A state-owned enterprise might variously operate as a not-for-profit corporation, as it may not be required to generate a profit; as a commercial enterprise in competitive sectors; or as a natural monopoly. Governments may also use the profitable entities they own to support the general budget. The creation of a state-owned enterprise from other forms of public property is called corporatization.

In Soviet-type economies, state property was the dominant form of industry as property. The state held a monopoly on land and natural resources, and enterprises operated under the legal framework of a nominally planned economy, operating according to different criteria than state and private enterprises in capitalistic market and mixed economies.

State-owned enterprise

A state-owned enterprise is a commercial enterprise owned by a government entity in a capitalist market or mixed economy. Reasons for state ownership of commercial enterprises are that the enterprise in question is a natural monopoly or because the government is promoting economic development and industrialization. State-owned enterprises may or may not be expected to operate in a broadly commercial manner and may or may not have monopolies in their areas of activity. The transformation of public entities and government agencies into government-owned corporations is sometimes a precursor to privatization.

State capitalist economies are capitalist market economies that have high degrees of government-owned businesses.

Relation to socialism

Public ownership of the means of production is a subset of social ownership, which is the defining characteristic of a socialist economy. However, state ownership and nationalization by themselves are not socialist, as they can exist under a wide variety of different political and economic systems for a variety of different reasons. State ownership by itself does not imply social ownership where income rights belong to society as a whole. As such, state ownership is only one possible expression of public ownership, which itself is one variation of the broader concept of social ownership.[3][4]

In the context of socialism, public ownership implies that the surplus product generated by publicly owned assets accrues to all of society in the form of a social dividend, as opposed to a distinct class of private capital owners. There is a wide variety of organizational forms for state-run industry, ranging from specialized technocratic management to direct workers' self-management. In traditional conceptions of non-market socialism, public ownership is a tool to consolidate the means of production as a precursor to the establishment of economic planning for the allocation of resources between organizations, as required by government or by the state.

State ownership is advocated as a form of social ownership for practical concerns, with the state being seen as the obvious candidate for owning and operating the means of production. Proponents assume that the state, as the representative of the public interest, would manage resources and production for the benefit of the public.[5] As a form of social ownership, state ownership may be contrasted with cooperatives and common ownership. Socialist theories and political ideologies that favor state ownership of the means of production may be labelled state socialism.

State ownership was recognized by Friedrich Engels in Socialism: Utopian and Scientific as, by itself, not doing away with capitalism, including the process of capital accumulation and structure of wage labor. Engels argued that state ownership of commercial industry would represent the final stage of capitalism, consisting of ownership and management of large-scale production and manufacture by the state.[6]

User rights

When ownership of a resource is vested in the state, or any branch of the state such as a local authority, individual use "rights" are based on the state's management policies, though these rights are not property rights as they are not transmissible. For example, if a family is allocated an apartment that is state owned, it will have been granted a tenancy of the apartment, which may be lifelong or inheritable, but the management and control rights are held by various government departments.[7]

Public property

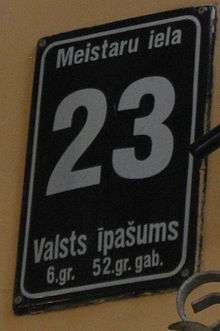

There is a distinction to be made between state ownership and public property. The former may refer to assets operated by a specific state institution or branch of government, used exclusively by that branch, such as a research laboratory. The latter refers to assets and resources that are available to the entire public for use, such as a public park (see public space).

Economic theory

In economics, the desirability of state ownership has been studied in contract theory. According to the property rights approach based on incomplete contracting (developed by Oliver Hart and his co-authors), ownership matters because it determines what happens in contingencies that were not considered in prevailing contracts.[8] The work by Hart, Shleifer and Vishny (1997) is the leading application of the property rights approach to the question whether state ownership or private ownership is desirable.[9] In their model, the government and a private firm can invest to improve the quality of a public good and to reduce its production costs. It turns out that private ownership results in strong incentives to reduce costs, but it may also lead to poor quality. Hence, depending on the available investment technologies, there are situations in which state ownership is better. The Hart-Shleifer-Vishny theory has been extended in many directions. For instance, some authors have also considered mixed forms of private ownership and state ownership.[10] Moreover, the Hart-Shleifer-Vishny model assumes that the private party derives no utility from provision of the public good. Besley and Ghatak (2001) have shown that if the private party (a non-governmental organization) cares about the public good, then the party with the larger valuation of the public good should always be the owner, regardless of the parties' investment technologies.[11] Yet, more recently some authors have shown that the investment technology also matters in the Besley-Ghatak framework if an investing party is indispensable[12] or if there are bargaining frictions between the government and the private party.[13]

See also

- State-owned enterprise

- Social ownership

- List of government-owned companies

- Municipalization

- Nationalization

- Public good

- Public sector

- Public finance

- Public property

References

- ↑ Clarke, Alison; Paul Kohler (2005). Property law: commentary and materials. Cambridge University Press. p. 40. ISBN 9780521614894.

- ↑ Gregory, Paul R.; Stuart, Robert C. (2003). Comparing Economic Systems in the Twenty-First Century. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 27. ISBN 0-618-26181-8.

There are three broad forms of property ownership-private, public, and collective (cooperative).

- ↑ Hastings, Mason and Pyper, Adrian, Alistair and Hugh (December 21, 2000). The Oxford Companion to Christian Thought. Oxford University Press. p. 677. ISBN 978-0198600244.

Socialists have always recognized that there are many possible forms of social ownership of which co-operative ownership is one. Nationalization in itself has nothing particularly to do with socialism and has existed under non-socialist and anti-socialist regimes. Kautsky in 1891 pointed out that a ‘co-operative commonwealth’ could not be the result of the ‘general nationalization of all industries’ unless there was a change in ‘the character of the state’.

- ↑ Ellman, Michael (1989). Socialist Planning. Cambridge University Press. p. 327. ISBN 0-521-35866-3.

State ownership of the means of production is not necessarily social ownership and state ownership can hinder efficiency.

- ↑ Arnold, Scott (1994). The Philosophy and Economics of Market Socialism: A Critical Study. Oxford University Press. p. 44. ISBN 978-0195088274.

For a variety of philosophical and practical reasons touched on in chapter 1, the most obvious candidate in modern societies for that role has been the state. In the past, this led socialists to favor nationalization as the primary way of socializing the means of production…The idea is that just as private ownership serves private interests, public or state ownership would serve the public interest.

- ↑ Frederick Engels. "Socialism: Utopian and Scientific (Chpt. 3)". Marxists.org. Retrieved 2014-01-08.

- ↑ Clarke, Alison; Paul Kohler (2005). Property law: commentary and materials. Cambridge University Press. p. 40. ISBN 9780521614894.

- ↑ Hart, Oliver (1995). "Firms, Contracts, and Financial Structure". Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Hart, Oliver; Shleifer, Andrei; Vishny, Robert W. (1997). "The Proper Scope of Government: Theory and an Application to Prisons". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 112 (4): 1127–1161. doi:10.1162/003355300555448. ISSN 0033-5533.

- ↑ Hoppe, Eva I.; Schmitz, Patrick W. (2010). "Public versus private ownership: Quantity contracts and the allocation of investment tasks". Journal of Public Economics. 94 (3–4): 258–268. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2009.11.009.

- ↑ Besley, Timothy; Ghatak, Maitreesh (2001). "Government versus Private Ownership of Public Goods". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 116 (4): 1343–1372. doi:10.1162/003355301753265598. JSTOR 2696461.

- ↑ Halonen-Akatwijuka, Maija (2012). "Nature of human capital, technology and ownership of public goods". Journal of Public Economics. Fiscal Federalism. 96 (11–12): 939–945. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2012.07.005.

- ↑ Schmitz, Patrick W. (2015). "Government versus private ownership of public goods: The role of bargaining frictions". Journal of Public Economics. 132: 23–31. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2015.09.009.